Stories with Intent: a Comprehensive Guide to the Parables of Jesus, Pp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ABSTRACT Following the Good Shepherd: the Patristic and Medieval Exegesis of John 10 and Luke 15 Christine Mcintire Director: D

ABSTRACT Following the Good Shepherd: The Patristic and Medieval Exegesis of John 10 and Luke 15 Christine McIntire Director: Daniel Nodes, Ph.D. This thesis presents an analysis of the exegetical tradition surrounding the Biblical image of sheep and shepherds. It focuses specifically on two parables given by Christ: The Parable of the Good Shepherd as recorded in John 10 and the Parable of the Lost Sheep as recorded in Luke 15. First, the Patristic and Medieval interpretations of each parable are addressed individually, identifying the ontological focus of the John 10 interpretations and the economical focus of the Luke 15 interpretations, noting a consistency of interpretations between the time periods. Finally, the thesis turns to Patristic and Medieval poetry, discovering them to blend the interpretations of each parable. This blend therefore provides an occasion for expressing the unified tradition of the sheep and shepherd image as a message of salvation. APPROVED BY DIRECTOR OF HONORS THESIS: ______________________________________________ Dr. Daniel Nodes, Department of Classics APPROVED BY THE HONORS PROGRAM: ______________________________________________________ Dr. Elizabeth Corey, Director DATE: ________________________ FOLLOWING THE GOOD SHEPHERD: THE PATRISTIC AND MEDIEVAL EXEGESIS OF JOHN 10 AND LUKE 15 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Baylor University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Honors Program By Christine McIntire Waco, Texas May 2019 The Lord is my shepherd; I shall not want. He makes me lie down in green pastures. He leads me beside still waters He restores my soul. He leads me in paths of righteousness for his name's sake. Even though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil, for you are with me; your rod and your staff, they comfort me. -

Good Shepherd Lutheran Church & School

Good Shepherd Lutheran Church & School 1611 E Main St., Watertown, WI 53094 Fourteenth Sunday after Pentecost September 15, 2019 “God is Still Doing What He’s Always Done” (Luke 15:1-3) Rev. David K. Groth “Now the tax collectors and “sinners” were all gathering around to hear Jesus. But the Pharisees and the teachers of the law muttered, ‘This man welcomes sinners and eats with them.’ Then Jesus told them this parable. .” (Luke 15:1-3). Every day, Everywhere, By Everyone,...sharing the grace of the Good Shepherd. Collect: Lord Jesus, You are the Good Shepherd, without whom nothing is secure. Rescue and preserve us that we may not be lost forever but follow You, rejoicing in the way that leads to eternal life; for You live and reign with the Father and the Holy Spirit, one God, now and forever. Amen Did you notice the contrast? The Pharisees and other religious authorities gathered around to mutter and grumble about Jesus. The sinners and tax collectors gathered around to listen to Jesus. The tax collectors, of course, were those treacherous collaborators who all but sold their souls and their country to the Romans for personal gain. The sinners were all those other men and women of ill repute, folks who didn’t even try to live by the law anymore. To associate with them was to be polluted by them. To befriend them and eat with them . unthinkable! But that’s precisely what Jesus did. Though they were oddballs and outcasts, Jesus slowed down and spent extra time with them, getting to know them so he could teach them and serve them. -

DYNAMIS – Orthodox Christian Prison Ministry * PO Box 277 * Rosemount, MN 55068

November 1 – Twenty-first Sunday after Pentecost, Tone 4 Saint Luke 8:26-39 To Meet God: Luke 8:26-39, especially vs. 28: “When he saw Jesus, he cried out, fell down before Him, and with a loud voice said, ‘What have I to do with You, Jesus, Son of the Most High God? I beg You, do not torment me!’” Many attempts had been made to control this possessed man-turned-beast, but “no one could bind him, not even with chains” (see also Mk 5:3; Mt 8:29). When the Lord Jesus came before him (Lk 8:27), the demoniac, out of agony, actually spoke with Jesus. To meet God is both arresting and healing. Why is this so? Because when we meet the One who is everything we are not, He draws us to become what we were created to be. Naked flesh becomes clothed in the Spirit, impurity is cleansed, death is restored to life, violence and wrath become gentle love, torment becomes passionlessness, fear becomes peace, and the self in bondage becomes self-controlled. The demon-possessed man “wore no clothes” (vs. 27) – not in order to protect the frenzied man from himself, but because his soul is drowning in the “filthiness of the flesh and spirit” (2 Cor 7:1). Then Christ comes and he is found “clothed and in his right mind” (Lk 8:35). When we bring catechumens to Christ, we beg God to clothe each one in “a robe of light,” since each of us is meant to grow in the glory of the Holy Trinity. -

The Beatitudes in Jesus' Life

CATECHIST RESOURCE The Beatitudes in Jesus’ Life 5–8 Luke 15 a distant country where he squandered his inheritance on a life of dissipation. When he The Parable of the Lost Sheep had freely spent everything, a severe famine The tax collectors and sinners were all drawing struck that country, and he found himself in near to listen to him, but the Pharisees and dire need. So he hired himself out to one of the scribes began to complain, saying, “This man local citizens who sent him to his farm to tend welcomes sinners and eats with them.” So to the swine. And he longed to eat his fill of the them he addressed this parable. “What man pods on which the swine fed, but nobody gave among you having a hundred sheep and losing him any. Coming to his senses he thought, ‘How one of them would not leave the ninety-nine many of my father’s hired workers have more in the desert and go after the lost one until he than enough food to eat, but here am I, dying finds it? And when he does find it, he sets it from hunger. I shall get up and go to my father on his shoulders with great joy and, upon his and I shall say to him, “Father, I have sinned arrival home, he calls together his friends and against heaven and against you. I no longer neighbors and says to them, ‘Rejoice with me deserve to be called your son; treat me as you because I have found my lost sheep.’ I tell you, would treat one of your hired workers.”’ So he in just the same way there will be more joy in got up and went back to his father. -

1 NT#19 Luke 15; 17 I. Introduction II. the Parable of the Lost Sheep III

NT#19 Luke 15; 17 I. Introduction II. The Parable of the Lost Sheep III. The Parable of the Lost Coin IV. The Parable of the Prodigal Son V. One of ten healed of Leprosy Returns VI. Conclusions I. Introduction In the three parables we will address, each addresses something that has been lost. In the first, an animal is lost; in the second, a coin and in the last, a son. I doubt that there many of us who have not had the experience of losing something that was of worth. The lost item may not have great monetary value, but its intrinsic value often drives the individual to go to great extremes in order to find that which is lost. We all know the relief that comes when the lost item is located and the joy that follows. When that which is lost is a son or daughter, the determination to find the one that is lost greatly increases. Nothing else matters, no expense too great, until contact is achieved. Only then can peace return to their loved ones. When no solution is found, despite all efforts, the ache for the lost one continues. It remains one of the sorrows some experience throughout their lives. Following our focus upon the noted parables, we will turn to the experience of ten men who are healed of leprosy. Only one returned. His purpose was to give to Jesus something the other nine keep to themselves. What was it? Why was it important? II. The Parable of the Lost Sheep We addressed this parable briefly in NT#15 as it is recorded in Matthew 18:12-14. -

Understanding Parables

Understanding Parables The Gospels of the New Testament are made up of a variety of literary forms. Miracle stories, conflict stories, pronouncement stories, sayings, and fulfillment citations are just a few examples. However, among all of the literary forms of the New Testament gospels, parables are the most familiar and often the least understood. In this essay, we will investigate the gospel parable as a literary form and comment on the art of interpreting parables as a proclamation of the kingdom of God. Understanding the characteristics of a particular literary form is important for right interpretation of a text. We cannot ask a text or any kind of media to answer questions that the author never intended to answer. For example, if we are reading an editorial in a newspaper, we should not expect to get unbiased, documentable evidence explaining both sides of the issue in question, but we can expect to read a rhetorically convincing, perhaps inflammatory, argument in support of a particular position. Likewise, if we are viewing a vampire movie, we should not expect to greet the vampire after the show, but we can expect to be entertained and even have an opportunity to reflect theologically or philosophically about fundamental questions like the nature of the afterlife or the problem of evil. When we are working with modern literary forms, we engage in this process of interpretation automatically and without much conscious reflection, because the forms are so familiar to us. However, the process of interpretation becomes much more complicated when we are dealing with ancient texts. -

The Parables of Luke

THE PARABLES OF LUKE Lord Jesus, we love You. Give us a deeper passion to know You and love You more. Give us a hunger and thirst for Your Word as we strive to become better followers of Christ. Amen. “If you want to know God, you have to know Him yourself. No one else can do it for you.,,You can only know Him through the written word He has left for you (the Bible) and through prayer.” David Wertz, Advent Devotional 2011, Dec. 8 Text: Poet & Peasant and Through Peasant Eyes, A Literary-Cultural Approach to the Parables in Luke; Combined Edition, Kenneth E. Bailey; William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., Grand Rapids, Mi. Jan. 8 Parable of the Unjust Steward (Luke 16:1-8) Jan. 15 Parable of a Friend At Midnight (Luke 11:5-13) Jan. 22 Parable of the Lost Sheep (Luke 15:3-7) Parable of the Lost Coin (Luke 15:8-10) Jan. 29 Parable of the Prodigal Son (Luke 15:9-32) Feb. 5 Parable of the Two Debtors (Luke 7:36-50) Feb. 12 Parable of the Good Samaritan (Luke 10:25-37) Feb. 19 Parable of the Rich Fool (Luke 12:13-21) Feb. 26 Parable of The Great Banquet (Luke 14:15-24) March 4 Parable of The Obedient Servant (Luke 17:7-10) March 18 Parable of The Judge and The Widow (Luke 18:1-8) March 25 Parable of The Pharisee and the Tax Collector (Luke 18:9-14) April 1 Parable of The Camel and The Needle (Luke 18:18-30) April 8 Easter Sunday – No Class Schedule is subject to change. -

Week Thirty-Four

PARABLES FOR THOUGHT Week 34: The More Difficult Parables of Jesus (Selections from the Four Gospels) Between heated confrontations, Jesus continued to teach His disciples quietly concerning the Kingdom of God. He used numerous methods of instruction. He employed hyperbole, warnings, laments, and denunciations. He presents truth through beatitudes, proverbs and dialogue. But of all His methods, perhaps the most interesting and distinctive mode of teaching was His use of parables. And although Jesus said the parables would have the effect of concealing truth (Mark 4), He must have had in mind those hearers whose hearts were closed to His teaching. Because, conversely, in fulfilling His mission statement as found in Luke, He preached to the poor and outcast making most of His lessons fairly simple to understand and especially well-suited for the common person. Simply explained but often practically difficult. There are around forty unique parables (see reverse side to see why it is difficult to discern between the various comparison literary devices) that are recounted in the Gospels. Jesus used parables to draw His listeners in and compel them to respond— either by pressing closer to grasp what Jesus meant or by giving up and walking away. These two types of responses are seen in the gospel accounts. Regarding these more difficult parables to understand, they are noticeably found in the latter half of the gospels as Jesus neared the last few weeks of His earthly life. As confrontation and opposition intensified, Jesus spoke all the more in para- bles and even more forcibly if the religious leaders were in the audience. -

Sermon: Luke 15. the Lost Sheep and the Lost Coin the Thing About The

Sermon: Luke 15. The Lost Sheep and the Lost Coin The thing about the two parables that form today's gospel is that they are very familiar and we have known them since Sunday School. And we tend to think that we just need to master the lesson in the parables for them and us to set things right in our lives. But it just might be that we are altogether wrong in how we understand them. It comes as a surprise to realize that parables are not all about us. Rather, the parables of Jesus are primarily about the mysterious way that God deals with us in the world. Jesus is a genius story teller, and each time you read the parables you will be surprised to discover twists and turns that you haven't noticed before, buried there in the familiar facts in subtle nuances and details. Luke's Gospel relates three parables about lostness, culminating in the greatest of them all, the Lost or Prodigal Son. But today we have the lost sheep and the lost coin. Luke begins by saying the tax collectors and the sinners were drawing near to Jesus to hear him. The Scribes and the Pharisees grumbled about this saying "This man welcomes sinners, and he eats with them, and therefore he's a bad person." By this stage in his ministry the crowds who flocked to hear Jesus were warming to the possibility that he might well be the promised Messiah who would fulfill God's will for Israel and do wonderful things in and for the world. -

Document Title

A NOW YOU KNOW MEDIA WRITTEN GUIDE A Retreat with the Gospel of Luke Presented by Fr. Felix Just, S.J., Ph.D. A RETREAT WITH THE GOSPEL OF LUKE WRITTEN GUID E Now You Know Media Copyright Notice: This document is protected by copyright law. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. You are permitted to view, copy, print and distribute this document (up to seven copies), subject to your agreement that: Your use of the information is for informational, personal and noncommercial purposes only. You will not modify the documents or graphics. You will not copy or distribute graphics separate from their accompanying text and you will not quote materials out of their context. You agree that Now You Know Media may revoke this permission at any time and you shall immediately stop your activities related to this permission upon notice from Now You Know Media. WWW.NOWYOUKNOWMEDIA.COM / 1 - 8 0 0 - 955- 3904 / © 2 0 1 2 2 A RETREAT WITH THE GOSPEL OF LUKE WRITTEN GUID E Table of Contents Program Summary ............................................................................................................... 4 About Your Presenter ........................................................................................................... 5 Conference 1: Luke’s Gospel and Prayer .......................................................................... 6 Conference 2: Luke’s Infancy Narrative .......................................................................... 11 Conference 3: Preparations for Jesus’ Ministry .............................................................. -

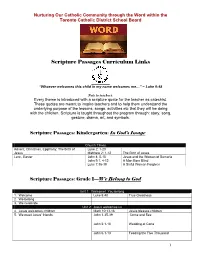

Scripture Passages Curriculum Links

Nurturing Our Catholic Community through the Word within the Toronto Catholic District School Board Scripture Passages Curriculum Links “Whoever welcomes this child in my name welcomes me…” ~ Luke 9:48 Note to teachers: Every theme is introduced with a scripture quote for the teacher as catechist. These quotes are meant to inspire teachers and to help them understand the underlying purpose of the lessons, songs, activities etc that they will be doing with the children. Scripture is taught throughout the program through: story, song, gesture, drama, art, and symbols. Scripture Passages: Kindergarten: In God’s Image Church TImes Advent, Christmas, Epiphany; The birth of Luke 2: 1-20 Jesus Matthew 2: 1-12 The Birth of Jesus Lent , Easter John 4: 5-15 Jesus and the Woman of Samaria John 9:1, 4-12 A Man Born Blind Luke 7:36-38 A Sinful Woman Forgiven Scripture Passages: Grade 1—We Belong to God Unit 1: Welcome! You belong 1. Welcome Luke 9.48 True Greatness 2. We belong 3. We celebrate Unit 2: Jesus welcomes us 4. Jesus welcomes children Mark 10:13-16 Jesus blesses children 5. We meet Jesus’ friends John 1.35-39 Come and See John 2.1-10 Wedding at Cana John 6.1-13 Feeding the Five Thousand 1 6. We are Jesus’ friends John 6.1-13 Feeding the Five Thousand Luke 11.5-8 Persistent Friend Luke 10.25-37 The Good Samaritan John 15.15 You Are My Friends Unit 3: We hear the story of God through Jesus 7. -

The Lost Sheep and Lost Coin

The Lost Sheep and Lost Coin ost churches, businesses, civic organizations and social groups want more members. Most people believe that success M is measured by the number of members or the amount of financial wealth. If one of the members becomes unhappy, it is rare that anyone chases after them in order to keep them unless they have been a significant member. Often, the gen- eral attitude is that it is probably best they left or, “We are sorry they left, but we have so many other members. Why should anyone be troubled? The rest of our group will go on. Why should any effort be given to one individual when the rest of the members need attention?” What attitude should Christians have toward those who are not believers who might visit the church and not return for some reason? What priority should we give to them? Some will say, “I hope they will return” and then start talking with a friend in the church about plans for lunch. Are you indifferent to unbelievers? In our study we will discover that God wants us to pursue those who have visited and left the church. Our study is Luke 15:1-10. It is about two parables: “The Lost Sheep” and “The Lost Coin.” Tax Collectors and Sinners. Time has elapsed ners. In Luke 7:34 Jesus announced to a crowd that the reli- since Jesus gave the parables and illustration in Luke 14. gious leaders condemned Christ because He ate and drank Luke 15 begins by telling us that those whom the religious with tax collectors and sinners.