Ministry Focus Paper Approval Sheet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Calm Year Is Our Women’S Leader- Beneath the Storm Ship Forum Here at Lifeway in Nashville, Tenn

Guest Editorial A WOMAN’S GUIDE TO INTIMACY When fall arrives, my ® WITH GOD mind turns to a busy season ourney of training women’s ministry J leaders. One of those training events I look forward to each The Calm year is our Women’s Leader- Beneath the Storm ship Forum here at LifeWay in Nashville, Tenn. If you lead women in your church, then you Redemptive Scars know that can be a blessing and a challenge Evidence of God’s at the same time. I’d like to invite you to join Life-Changing Love leaders from across the country that totally understand! This year’s forum will take place November 14-16, and our focus is “Filling Up and Pouring Out…Together!” This year’s guests include Angela Thomas, Margaret Feinberg, Esther Burroughs, and Vicki Courtney. Travis Cottrell will lead our worship and provide a wonderful concert on Friday night. Romans 15:13 tells us: “Now may the God of hope fi ll you with all joy and peace as you believe in Him so that you may overfl ow with hope by the power of the Holy Spirit.” If we don’t fi ll up, we can’t pour out effectively, and if we are full, then we MUST pour back into the lives of others. At this year’s forum you’ll fi nd out about: • Reaching for discipleship • Building community • Ministering out of the overfl ow • Connecting the generations of women I’d like to challenge older leaders with this question: What younger leader are you going to commit to bring with you? (And that actually includes YOU, no matter what age you are!) SEPTEMBER 2013 U.S.A. -

Great Things Verse Come Let Us Worship Our King Come Let Us Bow at His Feet He Has Done Great Things See What Our Savior Has D

Great Things Verse Come let us worship our King Come let us bow at His feet He has done great things See what our Savior has done See how His love overcomes He has done great things He has done great things Chorus Oh Hero of heaven, You conquered the grave You free every captive and break every chain Oh God, You have done great things We dance in Your freedom awake and alive Oh Jesus our Savior Your Name lifted high Oh God, You have done great things Verse You’ve been faithful through every storm You’ll be faithful forevermore You have done great things And I know You will do it again For Your promise is yes and amen You will do great things You will do great things Bridge Hallelujah, God above it all Hallelujah, God unshakeable Hallelujah, You have done great things You‘ve done great things CCLI Song # 7111321 Jonas Myrin | Phil Wickham © Capitol CMG Paragon (Admin. by Capitol CMG Publishing) Son of the Lion (Admin. by Capitol CMG Publishing) Phil Wickham Music (Fair Trade Music Publishing [c/o Essential Music Publishing LLC]) Simply Global Songs (Fair Trade Music Publishing [c/o Essential Music Publishing LLC]) Sing My Songs (Fair Trade Music Publishing [c/o Essential Music Publishing LLC]) CCLI License # 964729 Good Grace Verse People come together Strangers, neighbors our blood is one Children of generations Of every nation of Kingdom come Chorus So don’t let your heart be troubled, hold your head up high Don’t fear no evil, fix your eyes on this one truth God is madly in love with you So take courage hold on be strong Remember where our help comes from Verse Jesus our redemption Our salvation is in His blood Jesus Light of heaven Friend forever, His Kingdom come Chorus Bridge Swing wide all you heavens, let the praise go up as the walls come down All creation, everything with breath repeat the sound All His children, clean hands pure hearts Good grace, good God, His name is Jesus Joel Houston © 2018 Hillsong Music Publishing Australia (Admin. -

The Russians' Secret: What Christians Today Would Survive Persecution?

The Russians' Secret What Christians Today Would Survive Persecution? by Peter Hoover with Serguei V. Petrov Martyrdom, in early Christian times, already appealed to believers intent on doing great things for Christ. The early Christians venerated martyrs, the dates of whose executions grew into a calendar of saints, and wearing a martyrs' halo is still extremely popular. But martyr's halos do not come in the mail. A great amount of persecution faced by Christians today results not from what they believe, but from what they own, and from where they come. Missionaries in poor countries lose their possessions, and sometimes their lives, because people associate them with foreign wealth. Other "martyrs" lose their lives in political conflict. But does having our vehicles and cameras stolen, our children kidnapped, or being killed for political "correctness," assure that we have "witnessed for Jesus" (martyr means witness, Rev. 6:9, 12:17, and 19:10)? Real martyrs for Christ do not wear halos. They only carry crosses. Most people, even Christians, quickly discredit and forget these martyrs. Real martyrs suffer persecution, not like "great heroes of the faith" but like eccentrics and fools. Ordinary people usually consider them fanatics. Does that disappoint or alarm you? Do not worry. Reading this book about Russia's "underground" believers will assure you that if you are a typical Western Christian you will never face persecution. You will never have to be a real martyr for Christ. Only if you are not typical - if you choose to be a "weed that floats upstream" - you may want to know the secret by which Russian Christianity survived through a thousand years of suffering. -

Young Adult Library Services Association

THE OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF THE YOUNG ADULT LIBRARY SERVICES ASSOCIATION five ye ng ar ti s a o r f b y e a l l e s c young adult c e s l l e a b y r 5 f a t o in rs librarylibrary services services g five yea VOLUME 6 | NUMBER 2 WINTER 2008 ISSN 1541-4302 $12.50 INSIDE: INFORMATION TOOLS MUsiC WEB siTes TOP FIFTY GAMinG CORE COLLECTION TITLES INTERVIEW WITH KIMBERLY NEWTON FUSCO INFORMATION LITERACY AND MUCH MORE! TM ISSUE! TEEN TECH WEEK TM TM TEEN TECH WEEK MARCH 2-8, 2008 ©2007 American Library Association | Produced in partnership with YALSA | Design by Distillery Design Studio | www.alastore.ala.org march 2–8, 2008 for Teen Tech Week™ 2008! Join the celebration! Visit www.ala.org/teentechweek, and you can: ã Get great ideas for activities and events for any library, at any budget ã Download free tech guides and social networking resources to share with your teens ã Buy cool Teen Tech Week merchandise for your library ã Find inspiration or give your own ideas at the Teen Tech Week wiki, http://wikis.ala.org/yalsa/index.php/ Teen_Tech_Week! Teen Tech Week 2008 National Corporate Sponsor www.playdnd.com ttw_fullpage_cmyk.indd 1 1/3/2008 1:32:22 PM THE OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF THE YOUNG ADULT LIBRARY SERVICES ASSOCIATION young adult library services VOLUME 6 | NU MBER 2 WINTER 2008 ISSN 1541-4302 YALSA Perspective 33 Music Web Sites for Teen Tech Week 6 Margaret Edwards Award Turns 20 and Beyond By Betty Carter and Pam Spencer Holley By Kate Pritchard and Jaina Lewis 36 Top Fifty Gaming Core Collection Titles School Library Perspective Compiled by Kelly Czarnecki 14 Do We Still Dewey? By Christine Allen Literature Surveys and Research 39 Information Literacy As a Department Teen Perspective Store 15 Teens’ Top Ten Redux Applications for Public Teen Librarians Readers from New Jersey Talk about the By Dr. -

A Song for Us Pdf, Epub, Ebook

A SONG FOR US PDF, EPUB, EBOOK TERESA MUMMERT | 320 pages | 24 Apr 2014 | SIMON & SCHUSTER | 9781476732091 | English | New York, NY, United States A Song for Us PDF Book The lyrics also mention the atoning sacrifice of Jesus for our sins. Better Together 3 Luke Combs. And this is true for everyone who believes, no matter who we are. Dreams 5 Fleetwood Mac. Houston later recorded a studio version for her album, I Look to You. Lose You 4 Jordan Davis. Retrieved It also connects to us today, as people around us need the hope that Christ break to break through their present circumstances. The song has been recorded by both artists and has been made popular by Kari Jobe. February 25, Play music with Cortana Play your favorite artists, albums, tracks, or genres—even something based on your mood or activity, like workout music—using Cortana on your speaker or PC. Alice Tyson Coady Russell not only sings and plays piano on the recording, but also plays the tenor horn that is accompanying. Edit Storyline A musician revisits a long lost love from the Sixties and begins an emotional journey. He also performed it in the movie Honeysuckle Rose , and it appears on the movie's soundtrack. Hidden categories: Pages using infobox song with unknown parameters Articles with hAudio microformats. It is performed by Hillsong Worship. How can we improve? My Mommy and Papi were a big part of this music video and it was an incredible experience to create something as a family together. The bridge reminds us that God still works miracles and he turns our fears into faith. -

Pg0140 Layout 1

New Releases HILLSONG UNITED: LIVE IN MIAMI Table of Contents Giving voice to a generation pas- Accompaniment Tracks . .14, 15 sionate about God, the modern Bargains . .20, 21, 38 rock praise & worship band shares 22 tracks recorded live on their Collections . .2–4, 18, 19, 22–27, sold-out Aftermath Tour. Includes 31–33, 35, 36, 38, 39 the radio single “Search My Heart,” “Break Free,” “Mighty to Save,” Contemporary & Pop . .6–9, back cover “Rhythms of Grace,” “From the Folios & Songbooks . .16, 17 Inside Out,” “Your Name High,” “Take It All,” “With Everything,” and the Gifts . .back cover tour theme song. Two CDs. Hymns . .26, 27 $ 99 KTCD23395 Retail $14.99 . .CBD Price12 Inspirational . .22, 23 Also available: Instrumental . .24, 25 KTCD28897 Deluxe CD . 19.99 15.99 KT623598 DVD . 14.99 12.99 Kids’ Music . .18, 19 Movie DVDs . .A1–A36 he spring and summer months are often New Releases . .2–5 Tpacked with holidays, graduations, celebra- Praise & Worship . .32–37 tions—you name it! So we had you and all your upcoming gift-giving needs in mind when we Rock & Alternative . .10–13 picked the products to feature on these pages. Southern Gospel, Country & Bluegrass . .28–31 You’ll find $5 bargains on many of our best-sell- WOW . .39 ing albums (pages 20 & 21) and 2-CD sets (page Search our entire music and film inventory 38). Give the special grad in yourConGRADulations! life something unique and enjoyable with the by artist, title, or topic at Christianbook.com! Class of 2012 gift set on the back cover. -

Contemporary Issues: Dance, Drama, Powerpoint, and Body Posture and Unified Or Diverse Liturgies?

Christian Worship Lesson 19, page 1 Contemporary Issues: Dance, Drama, PowerPoint, and Body Posture And Unified or Diverse Liturgies? Let us pray. Father, we pray that as we try to apply biblical principles and truth to the contemporary issues of our day, some of the specific ones that we have not looked at but will begin to in this lesson, help us to hold tightly to Your principles and somewhat loosely to the manner of applying them into some of these practical areas. These areas change much with developing technology and the introduction of new ideas. Help us to be wise. Give us the gift of discernment and understanding as we go. We look to You to do this. In Jesus’ name, Amen. In the areas of dance, drama, film, PowerPoint, and body posture, I want to look at some of the questions that come up as we look at these contemporary issues in worship, many of which are specific to our North American context. We talked a little bit about dance when we were in Exodus 15 and 2 Samuel 6. Psalms 149 and 150 also call upon the people of God to dance in His presence. To me, the question of whether or not dancing can be done to the glory of God can be answered simply. Yes, dancing can be done to the glory of God. We saw it with Miriam and the women of Israel, we saw it with David, and we see it in Psalms 149 and 150. Let me read those verses from the Psalms specifically. -

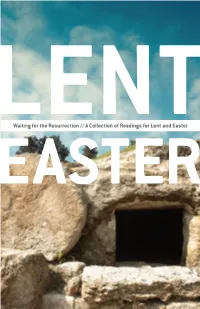

MBBS Lentdevotional Updated Size.Indd

Waiting for the Resurrection // A Collection of Readings for Lent and Easter Copyright © 2016 by Mennonite Brethren Biblical Seminary Waiting for the Resurrection: A Collection of Readings for Lent and Easter Printed in Canada ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Please visit us online at mbseminary.ca Cover design by Nova Hopkins Editing by Erika M. McAuley Second Printing by CP Printing Solutions, Winnipeg, Canada TO GOD BE THE GLORY To Our Readers Grace and peace to you from God our Father and the Lord Jesus Christ (Philippians 1:2). Greetings from the Mennonite Brethren Biblical Seminary Canada team! We are delighted this Lent and Easter devotional book has made its way into your home. The MBBS Canada team is very pleased to provide you with this wonderful resource for your enrichment as you prepare to celebrate the joyous resurrection of our Lord this Easter. We did our best to invite authors with a variety of disciplines, interests and locations across Canada to contribute to this project. The time and energy they took to carefully craft words with profundity and inspiration for our readers is much appreciated. Special thanks to Erika McAuley, the Project Editor, who worked tirelessly to make this project a success. Erika was responsible for inviting and collecting contributions from the authors and to lay out the biblical texts in a meaningful way. Her vision, insight and careful editorial work made this project extra special. Thank-you Erika! We are happy to provide this resource to you and your family and hope that it will inspire you and give you greater insight into your relationship to our Saviour and friend, Jesus Christ. -

D:\My Documents\` Songs\01-09\001 Ah! You're Beautiful.Sib

Ruth Fazal Songbook ributary Music Toronto, Canada Ah! You're Beautiful Ruth Fazal q = 70 Bb C/Bb F/A 1. Ah! You're beau -ti - ful, my love. 2. Ah! You're beau - ti - ful, my love. 3 Bb C/Bb F/A Ah! You're beau - ti - ful! Ah! You're beau - ti - ful! 5 Bb Bb/C C F F/A Bb More than my heart can ev - er know or ev - er feel; Be -yond the maj -tyes - of all that You have made; 7 Gm7 Bb/C C F F/A Je - sus, Your beau - ty is be - yond all that is real. Be - yond the splen - dour - of the power that You dis - play; Copyright © 1997 Ruth Fazal 2 9 Bb Bb/C C Dm F/A Bb Gm Gm/C More than my eyes have ev - er seen or ev - er will; Ah! You're beau - ti - ful, Je -sus, Your beau -isty be -yond all words I know. Ah! You're beau - ti - ful, 12 Asus ABbBb/C Ah! You're beau - ti - ful. Ah! You're beau - ti - ful. 14 F Bb/F C/E Dm F (From Jesus) 3. Ah! you're beautiful, my love 4. Ah! you're beautiful, my love Ah! you're beautiful Ah! you're beautiful More than your heart can ever know or ever feel Beyond the majesty of all that I have made My bride, my love for you surpasses all that's real Beyond the splendour of the power I've displayed More than your heart could ever know or understand My bride, your beauty is beyond all words you know Ah! you're beautiful. -

724349070998 25 Sunday School

UPC Title Artist Description SRP ReleaseDate Class Config CMTA Genre code ProdStatus 724349070998 25 Sunday School Songs 25 Kids Song Series Straightway Music $8.99 9/18/2003 Video DVD VHCHFB !None 820413126698 3-2-1 Penguins! The Complete Season 321 Penguins Big Idea $9.99 8/31/2012 Video DVD VHCHXX !None 819113010109 Mercy (Live) Aaron & Amanda Difference Media $19.99 9/15/2013 Video DVD VHMCXX !None 602537930296 Hero Advent Film Group AFG Movie Two $19.99 9/1/2014 Video DVD !None 617884918194 Angels Among Us Hymns & Gospel Alabama Gaither Music $19.99 8/3/2015 Video DVD VHMCXX !None 687797961198 Running Forever Alchemy First Look Studios $14.99 12/21/2015 Video DVD VHGNXX New Release 687797160195 My Dad's A Soccer Mom Alchemy First Look Studios $14.99 7/6/2015 Video DVD VHFFFE !None 687797158741 Brother's Keeper Combo Pack Alchemy First Look Studios $24.99 7/6/2015 Video DVD VHGNXX !None 687797158796 Brother's Keeper Alchemy First Look Studios $19.99 7/6/2015 Video DVD VHGNXX !None 687797160591 Comeback Dad Alchemy First Look Studios $14.99 7/6/2015 Video DVD VHFFFE !None 687797159694 Saving Westbrook High Alchemy First Look Studios $14.99 7/6/2015 Video DVD VHFFFE !None 687797160096 Back To The Jurassic Alchemy First Look Studios $14.99 5/25/2015 Video DVD VHFFFY !None 687797160294 Dinosaur Island Alchemy First Look Studios $14.99 5/25/2015 Video DVD VHFFFY !None 687797955296 A Gift Horse Alchemy First Look Studios $14.99 4/27/2015 Video DVD VHFFFY !None 888295059848 Messenger of the Truth Alchemy First Look Studios $19.99 2/16/2015 -

TG-Digital-Booklet.Pdf

There Is One Reason Greater Than We Can Imagine Verse 1 Verse 1 There is one reason why we’re gathered here Every day we’ll bless You and praise Your name Your love is causing us to sing And on Your glorious splendor we will dwell All of Your people through Your Son draw near On Your wondrous works, Lord, we’ll meditate Sinners before their holy King And of Your awesome power we will tell The church of God bought by blood We’ll speak of Your salvation And Your abundant goodness Chorus We love You, Father Chorus God of all, our God forever Because You are greater than we can imagine We praise You, Jesus You are too beautiful for us to fathom Christ our Lord, the Son, our Savior Oh You are great, and greatly to be praised We’re here together In Your Holy Spirit gathered for Your glory Verse 2 Every generation shall sing Your worth Verse 2 And magnify Your mercy and Your grace There’s a foundation that we’re building on We’ll sing about the Savior who came to earth Rooted in Jesus Christ alone To bear the sins of those He came to save Every believer firmly fixed upon You fill our hearts with wonder Our everlasting cornerstone We’ll worship You forever The church of God built by love Bridge One body, one baptism One hope to which we have been called One faith, one Lord, one Spirit One sovereign ruler over all We love You, Father We praise You, Jesus We’re here together For Your glory Music and words by Doug Plank Music and words by Mark Altrogge © 2011 Sovereign Grace Worship (ASCAP) © 2008 Sovereign Grace Praise (BMI) Come Praise and Glorify -

Order Hillsong Catalog Today!

DATE ACCOUNT # CUSTOMER NAME P.O. # SALES REP / REP # ORDER HILLSONG CATALOG TODAY! AVAILABLE NOW! Street Date: 5/18/10 Ship Date: 5/3/10 O rder Due Date: 4/15/10 (MAG) 4/30/10 (INDEPENDENTS) FORMAT UPC SRP QTY FORMAT UPC SRP QTY HILLSONG LIVE HILLSONG LIVE / FAITH + HOPE + LOVE (HILLSONG) MWMWXX CD $13.99 _____ 5 099962 966429 HILLSONG LIVE / FAITH + HOPE + LOVE DVD (HILLSONG) VHMCXX DVD $14.99 _____ 5 099962 966498 HILLSONG LIVE / THIS IS OUR GOD DVD (HILLSONG) VHMCXX DVD $14.99 _____ 5 099962 967495 HILLSONG LIVE / THIS IS OUR GOD (HILLSONG) MWMWXX CD $13.99 _____ 5 099962 967426 HILLSONG LIVE / SAVIOUR KING (HILLSONG) MWMWXX CD $13.99 _____ 5 099962 967525 HILLSONG LIVE / MIGHTY TO SAVE (HILLSONG) MWMWXX CD $13.99 _____ 5 099962 967624 HILLSONG UNITED HILLSONG UNITED / ACROSS THE EARTH: TEAR DOWN THE WALLS (HILLSONG) MWMWXX CD $13.99 _____ 5 099962 967822 HILLSONG UNITED / THE I HEART REVOLUTION DVD (HILLSONG) VHMCXX DVD $14.99 _____ 5 099962 967990 HILLSONG UNITED / THE I HEART REVOLUTION (HILLSONG) MWMWXX CD $18.99 _____ 5 099962 967921 101 WINNERS CIRCLE BRENTWOOD, TN 37027 Order at www.emicmgdistribution.com PRICES SUBJECT TO CHANGE WITHOUT NOTICE 1-800-877-4443 1 DATE ACCOUNT # CUSTOMER NAME P.O. # SALES REP / REP # ORDER HILLSONG CATALOG TODAY! AVAILABLE NOW! Street Date: 5/18/10 Ship Date: 5/3/10 O rder Due Date: 4/15/10 (MAG) 4/30/10 (INDEPENDENTS) FORMAT UPC SRP QTY FORMAT UPC SRP QTY HILLSONG UNITED / ALL OF THE ABOVE (HILLSONG) MWMWXX CD $13.99 _____ 5 099962 968829 HILLSONG UNITED / UNITED WE STAND (HILLSONG) MWMWXX CD