Consolidated Pastoral Co (CPC)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Economic Development in the Kimberley Region of Western Australia: a History and Dependency Theory Perspective

UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN QUEENSLAND Economic Development in the Kimberley Region of Western Australia: A History and Dependency Theory Perspective A dissertation submitted by Les Sharpe For the award of Doctor of Philosophy 2004 Abstract The focus of the research undertaken for this dissertation is the economic development of the Kimberley region of Western Australia. The period studied is, approximately, the one hundred years from 1900–2000. The region has many of the characteristics of an underdeveloped area and of a low income economy. This research used dependency theory as a framework for examining the causes of underdevelopment in the Kimberley. The development that occurred in the region during the relevant period has been catalogued by the creation of a database. This has enabled the collected information to be examined and manipulated in many ways. The database has allowed the detail of development in the Kimberley to be studied with respect to time, place and type of activity. This made it possible to examine the five hypotheses proposed by A. G. Frank which he considered likely to lead to fruitful research. The detailed study of these hypotheses would not have been possible in the way described without the database. It was found that dependency theory does help to explain and understand the development experience of the Kimberley region of Western Australia during the twentieth century. This was the clear and positive result of this study. The extension to Frank’s core dependency theory, the five hypotheses, were not found to be applicable to the Kimberley region nor supported by the data. -

PRG247 10-67 Lewisfamily Speciallists

___________________________________________________________________ LEWIS FAMILY PRG 247 Series 10-67 Special Lists Series 10 : Records relating to Newcastle Waters cattle station 1. Papers relating to the management of Newcastle Waters station 30 September 1902 – 22 October 1909. 3 cm. [Comprises correspondence (letters received and in some cases copies of letters sent) with managers and drovers; memoranda of agreement with drovers, and papers relating to cattle deliveries] 2. Balance sheets 30 September 1903 – 31 December 1906. 1 cm. 3. Papers relating to cattle sales 17 January 1902 – 27 March 1908. 1 cm. 4. Balance statements from Bagot, Shakes and Lewis, Limited 31 October 1905 – 27 August 1907. 9 items. 5. Inventories 25 July 1902 – 31 December 1906. 1 cm. 6. Plans of Newcastle Waters station nd. 2 items. 7. Photographs ca.1902. 3 items. Series 15 : Papers relating to explorers 1. Papers relating to John McDouall Stuart 25 July 1907 – 26 July 1912. 1 cm. [Includes a programme of a dinner given by the John McDouall Stuart Anniversary Committee to the survivors of the John McDouall Stuart exploring party on 25 July 1907; a typewritten copy of a speech given by John Lewis on the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of the crossing of Australia by Stuart, and newspaper cuttings on jubilee celebrations] PRG 247/10-67 Special lists Page 1 of 16 ___________________________________________________________________ 2. Papers relating to Captain Charles Sturt 28 November 1914 – 21 December 1916. 5 items. [Comprises a programme of the unveiling ceremony of the Sturt statue; typewritten copies of the address given by John Lewis as Chairman of the Sturt Committee at the unveiling ceremony; newspaper cuttings and photographs of Sturt, the Sturt statue, and scenes of the unveiling ceremony] 3. -

An Annotated Type Catalogue of the Dragon Lizards (Reptilia: Squamata: Agamidae) in the Collection of the Western Australian Museum Ryan J

RECORDS OF THE WESTERN AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM 34 115–132 (2019) DOI: 10.18195/issn.0312-3162.34(2).2019.115-132 An annotated type catalogue of the dragon lizards (Reptilia: Squamata: Agamidae) in the collection of the Western Australian Museum Ryan J. Ellis Department of Terrestrial Zoology, Western Australian Museum, Locked Bag 49, Welshpool DC, Western Australia 6986, Australia. Biologic Environmental Survey, 24–26 Wickham St, East Perth, Western Australia 6004, Australia. Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT – The Western Australian Museum holds a vast collection of specimens representing a large portion of the 106 currently recognised taxa of dragon lizards (family Agamidae) known to occur across Australia. While the museum’s collection is dominated by Western Australian species, it also contains a selection of specimens from localities in other Australian states and a small selection from outside of Australia. Currently the museum’s collection contains 18,914 agamid specimens representing 89 of the 106 currently recognised taxa from across Australia and 27 from outside of Australia. This includes 824 type specimens representing 45 currently recognised taxa and three synonymised taxa, comprising 43 holotypes, three syntypes and 779 paratypes. Of the paratypes, a total of 43 specimens have been gifted to other collections, disposed or could not be located and are considered lost. An annotated catalogue is provided for all agamid type material currently and previously maintained in the herpetological collection of the Western Australian Museum. KEYWORDS: type specimens, holotype, syntype, paratype, dragon lizard, nomenclature. INTRODUCTION Australia was named by John Edward Gray in 1825, The Agamidae, commonly referred to as dragon Clamydosaurus kingii Gray, 1825 [now Chlamydosaurus lizards, comprises over 480 taxa worldwide, occurring kingii (Gray, 1825)]. -

Grand Kimberley Travel Makers

Grand Kimberley Thursday 6th August to Thursday 20th August 2020 Travel the best of Kimberley exploring remote gorges, the stunning Savannah landscape and beau�ful Broome. DAY 1: Thu06Aug FLY TO BROOME – DERBY (D) Depart your home port and fly to Broome (own expense – latest arrival 11:30am) and on arrival meet your driver and hostess and travel inland toward the olde world town of Derby, located on the �dal mud flats on the edge of picturesque King Sound. The town’s origins were the pastoral and mining industries – Derby developed as a port to service the pastoral properRes along the Fitzroy River and pearl luggers used the port collec�ng in the Buccaneer Archipelago. Derby has the highest �dal range of any port in Australia. Overnight: Derby DAY 2: Fri 07 Aug WINDJANA GORGE – TUNNEL CK – FITZROY CROSSING (BLD) This morning we travel to visit Tunnel Creek – an underground stream located in the King Leopold Ranges to walk through the creek and marvel at this unique stream in its arid environment (please bring a torch and wet weather shoes). We then con�nue onto magnificent Windjana Gorge with its walls soaring 80 metres above the riverbed and enjoy time to walk into the gorge. We arrive at our des�na�on of Fitzroy Crossing in �me for dinner. Overnight: Fitzroy Crossing DAY 3: Sat 08 Aug FITZROY CROSSING – HALLS CREEK (BLD) A�er breakfast we travel to Danggu Gorge NaRonal Park to enjoy a leisurely cruise on Geikie Gorge to see the abundant wildlife and crocodiles sunning themselves on the banks of the river. -

Impacts and Management of Hard Water in Elliott, NT

Impacts and management of hard water in Elliott, NT. November 2007 prepared by Nerida Beard, Centre for Appropriate Technology, Alice Springs for the Elliott District Community Government Council. This work was funded by an ongoing initiative of the national Cooperative Research Centre for Water Quality and Treatment. Abstract Elliott District Community Government Council requested that CAT investigate their concerns over the impacts of calcium build up or ”scale‘ in the water supplies in their two community jurisdictions, Elliott township and Marlimja outstation (Newcastle Waters). Staff reported major pipe failures from calcium blockages. Community members and maintenance staff reported frequent failures of bathroom and household appliances such as toilet pans, toilet cisterns, hot water systems and tap fittings. Elliott Council executive reported that the impacts of frequent and recurring infrastructure failures bore a large cost burden on the Council, and diverted overstretched housing maintenance skills to the repair of community and household plumbing. It was also reported by the Council that there were ancillary concerns in the broader community population about human health impacts of the mineral concentration in the water supply. CAT inspected a number of houses in both the township and the outstation, the major water sources, storages and excavated pipe sections. Groundwater bore information was collated from Northern Territory Government archives (DNRETA 2007). Council staff, the School Principal and Health Workers were interviewed for their views, concerns and experiences of the water supply impacts. A range of hard water management options were suggested and discussed by field workers, including failure management, preventive maintenance and water treatment options. A focus group between key Council workers was held to discuss the alternatives, gain an understanding of community capacity for each solution and develop a locally appropriate strategy for hard water management. -

AUSTRALIAN BIOGRAPHY a Series That Profiles Some of the Most Extraordinary Australians of Our Time

STUDY GUIDE AUSTRALIAN BIOGRAPHY A series that profiles some of the most extraordinary Australians of our time Elizabeth Durack 1915–2000 Artist This program is an episode of Australian Biography Series 6 produced under the National Interest Program of Film Australia. This well-established series profiles some of the most extraordinary Australians of our time. Many have had a major impact on the nation’s cultural, political and social life. All are remarkable and inspiring people who have reached a stage in their lives where they can look back and reflect. Through revealing in-depth interviews, they share their stories— of beginnings and challenges, landmarks and turning points. In so doing, they provide us with an invaluable archival record and a unique perspective on the roads we, as a country, have travelled. Australian Biography: Elizabeth Durack Directors/Producers Robin Hughes, Linda Kruger Executive Producers Sharon Connolly, Megan McMurchy Duration 26 minutes Year 1997 © Film Australia Also in Series 6: Eva Burrows, Bruce Dawe, Margaret Fulton, Jimmy Little, B.A. Santamaria, A FILM AUSTRALIA NATIONAL INTEREST PROGRAM For more information about Film Australia’s programs, contact: Film Australia Sales, PO Box 46 Lindfield NSW 2070 Tel 02 9413 8634 Fax 02 9416 9401 Email [email protected] www.filmaust.com.au AUSTRALIAN BIOGRAPHY: ELIZABETH DURACK 2 SYNOPSIS Mark∑ on the map and research Thylungra Station, Ivanhoe Station and Argyle Downs Station. In 1997 the art world was shocked by the announcement from Western Australian artist Elizabeth Durack, that she and Aboriginal The Duracks and Aboriginal People artist, Eddie Burrup, whose work had recently begun to appear in art History has very little to say about Aboriginal people’s mistreatment galleries and exhibitions of Aboriginal art, were one and the same at the hands of dynastic families. -

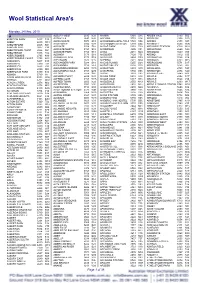

Wool Statistical Area's

Wool Statistical Area's Monday, 24 May, 2010 A ALBURY WEST 2640 N28 ANAMA 5464 S15 ARDEN VALE 5433 S05 ABBETON PARK 5417 S15 ALDAVILLA 2440 N42 ANCONA 3715 V14 ARDGLEN 2338 N20 ABBEY 6280 W18 ALDERSGATE 5070 S18 ANDAMOOKA OPALFIELDS5722 S04 ARDING 2358 N03 ABBOTSFORD 2046 N21 ALDERSYDE 6306 W11 ANDAMOOKA STATION 5720 S04 ARDINGLY 6630 W06 ABBOTSFORD 3067 V30 ALDGATE 5154 S18 ANDAS PARK 5353 S19 ARDJORIE STATION 6728 W01 ABBOTSFORD POINT 2046 N21 ALDGATE NORTH 5154 S18 ANDERSON 3995 V31 ARDLETHAN 2665 N29 ABBOTSHAM 7315 T02 ALDGATE PARK 5154 S18 ANDO 2631 N24 ARDMONA 3629 V09 ABERCROMBIE 2795 N19 ALDINGA 5173 S18 ANDOVER 7120 T05 ARDNO 3312 V20 ABERCROMBIE CAVES 2795 N19 ALDINGA BEACH 5173 S18 ANDREWS 5454 S09 ARDONACHIE 3286 V24 ABERDEEN 5417 S15 ALECTOWN 2870 N15 ANEMBO 2621 N24 ARDROSS 6153 W15 ABERDEEN 7310 T02 ALEXANDER PARK 5039 S18 ANGAS PLAINS 5255 S20 ARDROSSAN 5571 S17 ABERFELDY 3825 V33 ALEXANDRA 3714 V14 ANGAS VALLEY 5238 S25 AREEGRA 3480 V02 ABERFOYLE 2350 N03 ALEXANDRA BRIDGE 6288 W18 ANGASTON 5353 S19 ARGALONG 2720 N27 ABERFOYLE PARK 5159 S18 ALEXANDRA HILLS 4161 Q30 ANGEPENA 5732 S05 ARGENTON 2284 N20 ABINGA 5710 18 ALFORD 5554 S16 ANGIP 3393 V02 ARGENTS HILL 2449 N01 ABROLHOS ISLANDS 6532 W06 ALFORDS POINT 2234 N21 ANGLE PARK 5010 S18 ARGYLE 2852 N17 ABYDOS 6721 W02 ALFRED COVE 6154 W15 ANGLE VALE 5117 S18 ARGYLE 3523 V15 ACACIA CREEK 2476 N02 ALFRED TOWN 2650 N29 ANGLEDALE 2550 N43 ARGYLE 6239 W17 ACACIA PLATEAU 2476 N02 ALFREDTON 3350 V26 ANGLEDOOL 2832 N12 ARGYLE DOWNS STATION6743 W01 ACACIA RIDGE 4110 Q30 ALGEBUCKINA -

Mineralization and Geology of the North Kimberley

GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA REPORT 85 PLATE 1 è00 è25 128^30' è50 è75 129^00' å00 å25 127^30' å50 å75 128^00' ê00 REFERENCE ä25 126^30' ä50 ä75 127^00' 13^30' 126^00' ä00 13^30' q Quartz veins, of various ages; youngest post-dates Devonian q æåKk KEEP INLET FORMATION: deltaic sandstone, pebbly sandstone, mudstone, and minor coal æW Weaber Group: sandstone, limestone, and minor conglomerate, shale, and siltstone ðê00 ðê00 æL Langfield Group: sandstone, limestone, shale, and siltstone æåKk çma Limestone reef complexes; oolitic, cyanobacterial, and stromatolitic limestones, and debris flow deposits; BASIN Group Kulshill marginal slope and basin facies of Famennian reef carbonate; includes PIKER HILLS FORMATION and NORTHERN BONAPARTE T I M O R S E A VIRGIN HILLS FORMATION Branch Banks æW çg Boulder, cobble, and pebble conglomerate; includes BARRAMUNDI CONGLOMERATE and STONY CREEK CONGLOMERATE çN Ningbing Group: limestone reef complexes; cyanobacterial limestone, limestone breccia, shale, and sandstone East Holothuria Reef EARLY æL çC Cockatoo Group: sandstone, conglomerate, and limestone; minor dolomite and siltstone çM Mahony Group: quartz sandstone, pebbly sandstone, and pebble to boulder conglomerate CARBONIFEROUS êéc Carlton Group: shallow marine sandstone, siltstone, shale, and stromatolitic dolomite Otway Bank Stewart Islands êG Goose Hole Group: sandstone, limestone, stromatolitic limestone, siltstone, and mudstone çma çg çN çM Troughton Passage êa Vesicular, amygdaloidal, and porphyritic basalt, and conglomerate and sandstone; -

ABORIGINAL HISTORY 1979 3:2 Photograph Courtesy of Bruce Shaw

ABORIGINAL HISTORY 1979 3:2 Bruce Shaw and Jack Sullivan, Turkey Creek, October 1977 Photograph courtesy o f Bruce Shaw 9(1 ‘THEY SAME AS YOU AND ME’: ENCOUNTERS WITH THE GAD I A IN THE EAST KIMBERLEY Bruce Shaw and Jack Sullivan* Jack Sullivan was born on Argyle station in 1901 to a European father of the same name and a ‘fullblood’ Aboriginal woman of Djamindjung background. He grew up on the station and in his twenties ‘came over to the white side’, a choice which was explicitly presented by European station managers to many ‘half caste’ Aborigines when they came of age to enter fully into the stock work economy. The choice made was irreversible. Thereafter Jack never fully participated in the traditional ‘Law’ of the Aboriginal community to which he was related. A few years after the death of Patsy Durack in 1933, Jack ‘pulled out’ of Argyle station and followed the life style of the ‘bag man’, working on the Dunham River, Mabel Downs and Lissadell stations. In 1971, he retired from station life because of ill-health and set up camp with his fullblood half-brother Bulla Bilingiin on the Kununurra Aboriginal camping reserve (Mirima Village). I met him two years later and together we began recording his life history. Jack is one of the few remaining ‘old identities’ of the East Kimberley. Some anecdotes from his younger days are recorded by Mary Durack.1 The remini scences given here refer to the period between 1880 and his early childhood. Jack now lives in comfortable retirement at Turkey Creek. -

FIRST OVERLAND TRIP ADELAIDE – DARWIN SRG 37 MURRAY AUNGER and HARRY DUTTON, 1908 Series List Captions for the Pictorial Re

________________________________________________________________________ FIRST OVERLAND TRIP ADELAIDE – DARWIN SRG 37 MURRAY AUNGER AND HARRY DUTTON, 1908 Series List ________________________________________________________________________ Captions for the pictorial record of the trip. Captions run for pictures from left to right thus: 1. 2. Roll and frame numbers refer to the negatives kept 3. 4 with the albums. _______________________________________________________________________ ALBUM ONE ______________________________________________________________________ Page/Photo Captions Roll Frame ________________________________________________________________________ 1/1 On the track just south of Oodnadatta. 1 43 Harry Dutton is in the picture and the railway line can be seen in the background. 1/2 On the track just south of Oodnadatta. ― 44 1/3 Depot Sandhills four miles north of ― 1 Horse Shoe Bend. 1/4 Part of Horse Shoe Bend Station ― 45 showing the "painted cliffs". 2/1 Mount Dutton, south of Oodnadatta. ― 2 2/2 The railway line approaching Oodnadatta. ― 3 2/3 One of the many sandy water courses. ― 5 2/4 Granite stones between Oodnadatta ― 4 and Horse Shoe Bend. 3/1 Stony outcrop south of Oodnadatta. ― 6 3/2 Crossing Niels Creek by the Algebuckina Bridge. ― 8 3/3 On the track just south of Oodnadatta. ― 7 3/4 Oodnadatta. ― 9 4/1 Oodnadatta railway station and township. ― 10 4/2 Blood's Creek Hotel. ― 12 4/3 Watercourse near crown point. The bank 1 11 has to be broken down for the crossing. 4/4 Crown Point. The flat top is ironstone. ― 13 SRG 37/3 Series list Page 1 of 9 ________________________________________________________________________ This is said to have been the original height of the surrounding country. 5/1 Horse Shoe Bend station. -

MS 727 Lists of Peter Sutton's Archives in His Own Hands And

AIATSIS Collections Catalogue Manuscript Finding Aid index Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Library MS 727 Lists of Peter Sutton’s archives in his own hands and those he donated to the South Australian Museum Archives 2009-2012 CONTENTS COLLECTION SUMMARY ........................................................................................... 2 CULTURAL SENSITIVITY STATEMENT ..................................................................... 2 ACCESS TO COLLECTION ........................................................................................ 3 COLLECTION OVERVIEW .......................................................................................... 3 BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE ............................................................................................... 4 SERIES DESCRIPTION .............................................................................................. 6 BOX LIST ................................................................................................................. 192 MS 727, Lists of Peter Sutton’s archives in his own hands and those he donated to the South Australian Museum Archives, 2009 - 2012 COLLECTION SUMMARY Creator: Peter Sutton Title: Lists of Professor Sutton’s archives in his own hands and those he donated to the South Australian Museum Archives Collection no: MS 727 Date range: 2009 – 2012 Extent: 1 box Repository: Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies CULTURAL SENSITIVITY STATEMENT It is a condition -

Indigenous Climate Change Adaptation in the Kimberley Region of North-Western Australia

Indigenous climate change adaptation in the Kimberley region of North-western Australia Final Report Sonia Leonard, John Mackenzie, Frances Kofod, Meg Parsons, Marcia Langton, Peter Russ, Lyndon Ormond-Parker, Kristen Smith and Max Smith Indigenous climate change adaptation in the Kimberley region of North-western Australia Learning from the past, adapting in the future: Identifying pathways to successful adaptation in Indigenous communities AUTHORS Sonia Leonard John Mackenzie Frances Kofod Meg Parsons Marcia Langton Peter Russ Lyndon Ormond-Parker Kristen Smith Max Smith Published by the National Climate Change Adaptation Research Facility 2013 ISBN: 978-1-925039-87-0 NCCARF Publication 116/13 Australian copyright law applies. For permission to reproduce any part of this document, please approach the authors. Please cite this report as: Leonard, S, Mackenzie, J, Kofod, F, Parsons, M, Langton, M, Russ, P, Ormond-Parker, L, Smith, K & Smith, M 2013, Indigenous climate change adaptation in the Kimberley region of North-western Australia. Learning from the past, adapting in the future: Identifying pathways to successful adaptation in Indigenous communities, National Climate Change Adaptation Research Facility, Gold Coast, 131 pp. Acknowledgment This work was carried out with financial support from the Australian Government (Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency) and the National Climate Change Adaptation Research Facility (NCCARF). The role of NCCARF is to lead the research community in a national interdisciplinary effort to generate the information needed by decision-makers in government, business and in vulnerable sectors and communities to manage the risk of climate change impacts. Disclaimer The views expressed herein are not necessarily the views of the Commonwealth or NCCARF, and neither the Commonwealth nor NCCARF accept responsibility for information or advice contained herein.