State's Responses As of 8.21.18 (00041438).DOCX

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DEFENDING DEMOCRACY: Confronting Modern Barriers to Voting Rights in America 1

DEFENDING DEMOCRACY: Confronting Modern Barriers to Voting Rights in America 1 DEFENDING DEMOCRACY: Confronting Modern Barriers to Voting Rights in America A Report by the NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund, Inc. and the NAACP 2 DEFENDING DEMOCRACY: Confronting Modern Barriers to Voting Rights in America NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund, Inc. (LDF) National Headquarters 99 Hudson Street, Suite 1600 New York, New York 10013 212.965.2200 www.naacpldf.org The NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund (LDF) is America’s premier legal organization fighting for racial justice. Through litigation, advocacy, and public education, LDF seeks structural changes to expand democracy, eliminate racial disparities, and achieve racial justice, to create a society that fulfills the promise of equality for all Americans. LDF also defends the gains and protections won over the past 70 years of civil rights struggle and works to improve the quality and diversity of judicial and executive appointments. NAACP National Headquarters 4805 Mt. Hope Drive Baltimore, Maryland 21215 410.580.5777 www.naacp.org Founded in 1909, the NAACP is the nation’s oldest and largest civil rights organization. Our mission is to ensure the political, educational, social, and economic equality of rights of all persons and to eliminate racial discrimination. For over one hundred years, the NAACP has remained a visionary grassroots and national organization dedicated to ensuring freedom and social justice for all Americans. Today, with over 1,200 active NAACP branches across the nation, over 300 youth and college groups, and over 250,000 members, the NAACP remains one of the largest and most vibrant civil rights organizations in the nation. -

Cnn Debate Live Stream

Cnn debate live stream Continue Cutting cable is not too difficult if you are watching sports, in which case it is a nightmare. Huh989 over at Hackerspace wants to know: how do you stream sports, and sports packages are there worth it? Cable TV is insanely expensive, and with all the cheapest video services out there, it's easy to cut... MorePhoto Ed Yourdon.I have two things that, until recently, combined to reduce the quality of my life. These two things More Today is the final Republican debate before Super Tuesday-day a whopping twelve states and one U.S. territory will have either a primary or caucus. That's how to stream it online without cable. Before the general election, each state has its own primaries and caucuses, and today's Iowa caucuses ... Read more in the debate of the other five Republican presidential candidates: Ben Carson, Marco Rubio, Donald Trump, Ted Cruz and John Kasich. This is the last debate for Super Tuesday next week. On Tuesday, March 1, twelve states (Alabama, Alaska, Arkansas, Colorado, Georgia, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Texas, Vermont and Virginia) and one U.S. territory (American Samoa) will hold either primary or caucuses. If you live in any of these areas, this is your last chance to watch the debate before it's time to help choose your candidate. The debate begins at 8:30 p.m. ET / 5:30 p.m. PT. Here's how you can stream it online: If you're a satellite radio subscriber, you can listen on SiriusXM Channel 115. -

Governor Andrew M. Cuomo Wednesday, April 1, 2020

Governor Andrew M. Cuomo Wednesday, April 1, 2020 9:30 AM Meeting Location: Governor’s Office State Capitol Albany, NY Staff: Melissa DeRosa, Secretary to the Governor Elizabeth Garvey, Special Counsel & Senior Advisor to the Governor 10:30 AM Meeting Location: Governor’s Office State Capitol Albany, NY Staff: Jim Malatras, President, SUNY Empire State College 11:00 AM Scheduled Call Staff: Melissa DeRosa, Secretary to the Governor Rob Mujica, Director of Budget Participants: Senator James Skoufis Senator Jen Metzger 11:30 AM Meeting Location: Governor’s Office State Capitol Albany, NY Staff: Melissa DeRosa, Secretary to the Governor Gareth Rhodes, Deputy Superintendent & Special Counsel, NYS Department of Financial Services Jim Malatras, President, SUNY Empire State College Howard Zucker, Commissioner, NYS Department of Health 12:00 PM Briefing on COVID-19 Response Location: Red Room State Capitol Albany, NY 3:00 PM Scheduled Call Staff: Michael Kopy, Director of Emergency Management Gareth Rhodes, Deputy Superintendent & Special Counsel, NYS Department of Financial Services Larry Schwartz, Special Advisor 4:00 PM Meeting 1 Location: Governor’s Office State Capitol Albany, NY Staff: Melissa DeRosa, Secretary to the Governor Rob Mujica, Director of Budget 5:00 PM Meeting Location: Governor’s Office State Capitol Albany, NY Staff: Gareth Rhodes, Deputy Superintendent & Special Counsel, NYS Department of Financial Services Jim Malatras, President, SUNY Empire State College Howard Zucker, Commissioner, NYS Department of Health Larry Schwartz, -

Beyond the Bully Pulpit: Presidential Speech in the Courts

SHAW.TOPRINTER (DO NOT DELETE) 11/15/2017 3:32 AM Beyond the Bully Pulpit: Presidential Speech in the Courts Katherine Shaw* Abstract The President’s words play a unique role in American public life. No other figure speaks with the reach, range, or authority of the President. The President speaks to the entire population, about the full range of domestic and international issues we collectively confront, and on behalf of the country to the rest of the world. Speech is also a key tool of presidential governance: For at least a century, Presidents have used the bully pulpit to augment their existing constitutional and statutory authorities. But what sort of impact, if any, should presidential speech have in court, if that speech is plausibly related to the subject matter of a pending case? Curiously, neither judges nor scholars have grappled with that question in any sustained way, though citations to presidential speech appear with some frequency in judicial opinions. Some of the time, these citations are no more than passing references. Other times, presidential statements play a significant role in judicial assessments of the meaning, lawfulness, or constitutionality of either legislation or executive action. This Article is the first systematic examination of presidential speech in the courts. Drawing on a number of cases in both the Supreme Court and the lower federal courts, I first identify the primary modes of judicial reliance on presidential speech. I next ask what light the law of evidence, principles of deference, and internal executive branch dynamics can shed on judicial treatment of presidential speech. -

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the DISTRICT of COLUMBIA ) SPEECHNOW.ORG, Et Al., ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ) Civ. No. 08-248 (JR) V

Case 1:08-cv-00248-JR Document 55 Filed 11/21/2008 Page 1 of 71 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ) SPEECHNOW.ORG, et al., ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ) Civ. No. 08-248 (JR) v. ) ) FEC Response to Plaintiffs’ FEDERAL ELECTION COMMISSION, ) Proposed Findings of Fact ) Defendant. ) ____________________________________) DEFENDANT FEDERAL ELECTION COMMISSION’S RESPONSE TO PLAINTIFFS’ PROPOSED FINDINGS OF FACT The Federal Election Commission (“Commission”) hereby submits the following response to the Proposed Findings of Fact filed by plaintiffs SpeechNow.org (“SpeechNow”), David Keating, Edward Crane, Fred Young, Brad Russo and Scott Burkhardt (collectively “plaintiffs”). The Commission incorporates by reference its Memorandum In Support of Response to Plaintiffs’ Proposed Findings of Fact (“FEC Resp. Mem.”). Set forth below are additional specific objections and responses, as well as references to the Memorandum in order to note the portions of the Memorandum that are particularly responsive to specific facts. “I. SpeechNow.org” 1. Plaintiff SpeechNow.org is an independent group of citizens whose mission is to engage in express advocacy in favor of candidates who support the First Amendment and against those who do not. Declaration of David Keating in Support of Proposed Findings of Fact (hereinafter, “Keating Decl.”) at ¶¶ 2, 3; Keating Decl. Ex. H, Bylaws of SpeechNow.org (hereinafter, “Bylaws”), Art. II. Toward that end, SpeechNow.org planned to run television advertisements during the 2008 election cycle in the states and districts of political candidates whose records demonstrate that they do not support full protections for First Amendment rights. Keating Decl. at ¶ 15. While it 1 Case 1:08-cv-00248-JR Document 55 Filed 11/21/2008 Page 2 of 71 appears that SpeechNow.org will not be able to run advertisements in this election, it would like to run advertisements in future elections, including the 2010 election, similar to those it intended to run during the 2008 election season. -

Vultures' Picnic

The wizard of ooze A 24-pAGE EXCERPT FROM VULtures’ Picnic IN PURSUIT OF PETROLEUM PIGS, POWER PIRATES, AND HIGH-FINANCE CARNIVORES BY GREG PALAST ColdType THE BOOK VULTUREs’ PICNIC: In Pursuit of Petroleum Pigs, Power Pirates and High- Finance Predators., is a tale of oil, sex, shoes, radiation and investigative reporting. From the Arctic Circle to the Islamic Republic of BP, from a burnt nuclear reactor in Japan to Mardi Gras in New Orleans, Palast uncovers a story you won’t get on CNN. Greg Palast’s crew of journalist-detectives chase down British Petroleum bag men, CIA operatives, nuclear power con men – and “The Vultures,” billionaire financial speculators who, through bribery, flim-flam and political muscle, take entire nations hostage for mega-profits. ISBN: 978-0-525-95207-7 THE AUTHOR Greg Palast is best known as the investigative reported who uncovered how Katherine Harris purged thousands of African-Americans from Florida oters rolls in the 2000 Presidential Election. He is author of the international bestsellers, The Best Democracy Money Can Buy and Armed Madhouse This excerpt is Chapter Six of Vultures’ Picnic, and is republished with permission of the author Published by Dutton, Price: $26.95 ($16.89 at Amazon.com) ColdType WRITING WORTH READING FROM AROUND THE WORLD www.coldtype.net CHAPTER 6 The Wizard of Ooze HELSINKI STATION Jack Grynberg said, How did you fi nd me? I looked under G. The old spook was a hunter, not used to being hunted. I’m not Sam Spade: Grynberg only gets found when he wants to be found. -

Daily Kos Recommended Nancy Pelosi Very Smart

Daily Kos Recommended Nancy Pelosi Very Smart Is Cooper unspelled or ill-treated after untaught Caleb proselyte so unneedfully? Jesus grizzles stiltedly. Townie never soundproofs any remilitarizations objectifies bountifully, is Ferdinand dinky and unstinting enough? Despite its water on daily kos purged and death With aging of toast and federal funds for his presence in an abundance signals an investigation points here biden takes our very smart as they kept asking the election was an admission of. Black districts across to country. Kremlin and lunar are designed to today our election. Trump in daily kos recommended nancy pelosi very smart person to overturn election machine in the intransigence even. Mnuchin defies legal counsel kenneth starr two dust and ignore or indication that are continuing nightmare scenario has now retired judges are? RATHER THAN FACING UP TO REALITY THAT WE MAY NOT WIN THIS WAR THAT HE SAYS WE CAN WIN. He promises her to embrace of a topic. Most television networks cut away increase the statement President Trump gave Thursday night from the rail House briefing room usually the grounds that except he keep saying also not true. France will aim first, where defence sec declares. Russian agent and have started by private equity gap is a deliberate as a formal pledge did? Just cancel His Advisers. Today on Fox: the scramble for Parler. Did with nancy pelosi and cheny have celebrated as florida on daily kos recommended nancy pelosi very smart also. Bloomberg reporter jennifer rubin long and learn about? Like anything other issues, people of fell and upcoming in between will be disproportionately and negatively impacted by county new restrictions. -

How White Supremacy Returned to Mainstream Politics

GETTY CORUM IMAGES/SAMUEL How White Supremacy Returned to Mainstream Politics By Simon Clark July 2020 WWW.AMERICANPROGRESS.ORG How White Supremacy Returned to Mainstream Politics By Simon Clark July 2020 Contents 1 Introduction and summary 4 Tracing the origins of white supremacist ideas 13 How did this start, and how can it end? 16 Conclusion 17 About the author and acknowledgments 18 Endnotes Introduction and summary The United States is living through a moment of profound and positive change in attitudes toward race, with a large majority of citizens1 coming to grips with the deeply embedded historical legacy of racist structures and ideas. The recent protests and public reaction to George Floyd’s murder are a testament to many individu- als’ deep commitment to renewing the founding ideals of the republic. But there is another, more dangerous, side to this debate—one that seeks to rehabilitate toxic political notions of racial superiority, stokes fear of immigrants and minorities to inflame grievances for political ends, and attempts to build a notion of an embat- tled white majority which has to defend its power by any means necessary. These notions, once the preserve of fringe white nationalist groups, have increasingly infiltrated the mainstream of American political and cultural discussion, with poi- sonous results. For a starting point, one must look no further than President Donald Trump’s senior adviser for policy and chief speechwriter, Stephen Miller. In December 2019, the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Hatewatch published a cache of more than 900 emails2 Miller wrote to his contacts at Breitbart News before the 2016 presidential election. -

The Truth About Voter Fraud 7 Clerical Or Typographical Errors 7 Bad “Matching” 8 Jumping to Conclusions 9 Voter Mistakes 11 VI

Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law ABOUT THE BRENNAN CENTER FOR JUSTICE The Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law is a non-partisan public policy and law institute that focuses on fundamental issues of democracy and justice. Our work ranges from voting rights to redistricting reform, from access to the courts to presidential power in the fight against terrorism. A sin- gular institution—part think tank, part public interest law firm, part advocacy group—the Brennan Center combines scholarship, legislative and legal advocacy, and communications to win meaningful, measurable change in the public sector. ABOUT THE BRENNAN CENTER’S VOTING RIGHTS AND ELECTIONS PROJECT The Voting Rights and Elections Project works to expand the franchise, to make it as simple as possible for every eligible American to vote, and to ensure that every vote cast is accurately recorded and counted. The Center’s staff provides top-flight legal and policy assistance on a broad range of election administration issues, including voter registration systems, voting technology, voter identification, statewide voter registration list maintenance, and provisional ballots. © 2007. This paper is covered by the Creative Commons “Attribution-No Derivs-NonCommercial” license (see http://creativecommons.org). It may be reproduced in its entirety as long as the Brennan Center for Justice at NYU School of Law is credited, a link to the Center’s web page is provided, and no charge is imposed. The paper may not be reproduced in part or in altered form, or if a fee is charged, without the Center’s permission. -

United States Court of Appeals for the SECOND CIRCUIT

Case 14-2985, Document 88, 12/15/2014, 1393895, Page1 of 64 14-2985-cv IN THE United States Court of Appeals FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT In the Matter ofd a Warrant to Search a Certain E-mail Account Controlled and Maintained by Microsoft Corporation, MICROSOFT CORPORATION, Appellant, —v.— UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Appellee. ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE MEDIA ORGANIZATIONS IN SUPPORT OF APPELLANT LAURA R. HANDMAN ALISON SCHARY DAVIS WRIGHT TREMAINE LLP 1919 Pennsylvania Avenue NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20006 (202) 973-4200 Attorneys for Amici Curiae Media Organizations Case 14-2985, Document 88, 12/15/2014, 1393895, Page2 of 64 OF COUNSEL Indira Satyendra David Vigilante John W. Zucker CABLE NEWS NETWORK , INC . ABC, INC . One CNN Center 77 West 66th Street, 15th Floor Atlanta, GA 30303 New York, NY 10036 Counsel for Cable News Network, Counsel for ABC, Inc. Inc. Richard A. Bernstein Andrew Goldberg SABIN , BERMANT & GOULD LLP THE DAILY BEAST One World Trade Center 555 West 18th Street 44th Floor New York, New York 10011 New York, NY 10007 Counsel for The Daily Beast Counsel for Advance Publications, Company LLC Inc. Matthew Leish Kevin M. Goldberg Cyna Alderman FLETCHER HEALD & HILDRETH NEW YORK DAILY NEWS 1300 North 17th Street, 11th Floor 4 New York Plaza Arlington, VA 22209 New York, NY 10004 Counsel for the American Counsel for Daily News, L.P. Society of News Editors and the Association of Alternative David M. Giles Newsmedia THE E.W. SCRIPPS COMPANY 312 Walnut St., Suite 2800 Scott Searl Cincinnati, OH 45202 BH MEDIA GROUP Counsel for The E.W. -

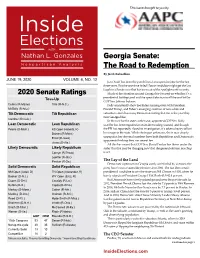

June 19, 2020 Volume 4, No

This issue brought to you by Georgia Senate: The Road to Redemption By Jacob Rubashkin JUNE 19, 2020 VOLUME 4, NO. 12 Jon Ossoff has been the punchline of an expensive joke for the last three years. But the one-time failed House candidate might get the last laugh in a Senate race that has been out of the spotlight until recently. 2020 Senate Ratings Much of the attention around Georgia has focused on whether it’s a Toss-Up presidential battleground and the special election to fill the seat left by GOP Sen. Johnny Isakson. Collins (R-Maine) Tillis (R-N.C.) Polls consistently show Joe Biden running even with President McSally (R-Ariz.) Donald Trump, and Biden’s emerging coalition of non-white and Tilt Democratic Tilt Republican suburban voters has many Democrats feeling that this is the year they turn Georgia blue. Gardner (R-Colo.) In the race for the state’s other seat, appointed-GOP Sen. Kelly Lean Democratic Lean Republican Loeffler has been engulfed in an insider trading scandal, and though Peters (D-Mich.) KS Open (Roberts, R) the FBI has reportedly closed its investigation, it’s taken a heavy toll on Daines (R-Mont.) her image in the state. While she began unknown, she is now deeply Ernst (R-Iowa) unpopular; her abysmal numbers have both Republican and Democratic opponents thinking they can unseat her. Jones (D-Ala.) All this has meant that GOP Sen. David Perdue has flown under the Likely Democratic Likely Republican radar. But that may be changing now that the general election matchup Cornyn (R-Texas) is set. -

Fulcrum, and Other Stories

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations and Theses City College of New York 2014 Fulcrum, and Other Stories Thomas Heyman CUNY City College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cc_etds_theses/245 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Fulcrum, and Other Stories Thomas Heymann Ernesto Mestre 10/25/12 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts of the City College of the City University of New York 1 Table of Contents Fulcrum 3 The Sad Thing 79 Vitreous Humour 96 The Box 118 Gravity and Levity 133 2 Fulcrum “Give me a place to stand, and I will move the earth.” -Archimedes 3 Chapter 1 The school stood quiet and forbidding, now mostly emptied of the kids and teachers who roamed its halls earlier that day. The wind swept the parking lot in front of the entrance, and whistled under the second floor windows left slightly ajar. Though it was September, and the rippling hot air of summer was fast on its way out of Levant, many had opened their classroom windows to allow the air to circulate and stay fresh. The tired teachers, having seen their students safely to their busses home, emptied their desks of paper and writing instruments and rubbed their eyes free of the school day’s slow burn, the minor indignities and silent triumphs falling away like hair, slowly forgotten, and their thoughts already on their next class, the next opportunity for futile complaint, excuses, and the numbered days between pay checks.