Security Practices, Subsuming Elements from Constructivist Approaches to Security, Such As the Aberystwyth, Copenhagen, and Paris Approaches (Wæver 2004; C.A.S.E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Swedish Olympic Team TOKYO 2020

Swedish Olympic Team TOKYO 2020 MEDIA GUIDE - SWEDISH OLYMPIC TEAM, TOKYO 2020 3 MEDIA GUIDE SWEDEN This Booklet, presented and published by the Swedish Olympic Committee is intended to assist members of the media at the Games of the XXXII Olympiad. Information is of July 2021. For late changes in the team, please see www.sok.se. Location In northern Europe, on the east side of the Scandi- navian Peninsula, with coastline on the North and Baltic seas and the Gulf of Bothnia. Neighbours Norway on the East. Mountains along Northwest border cover 25 per cent of Sweden. Flat or rolling terrain covers central and southern areas which includes several large lakes. Official name: Konungariket Sverige (Kingdom of Sweden). Area: 447 435 km2 (173 732 sq. miles). Rank in the world: 57. Population: 10 099 265 Capital: Stockholm Form of government: Constitutional monarchy and parliamentary state with one legislative house (Parlia- ment with 349 seats). Current constitution in force since January 1st, 1975. Chief of state: King Carl XVI Gustaf, since 1973. Head of government: Prime Minister Stefan Löfven, since 2014. Official language: Swedish. Monetary unit: 1 Swedish krona (SEK) = 100 öre. MEDIA GUIDE - SWEDISH OLYMPIC TEAM, TOKYO 2020 4 ANSVARIG UTGIVARE Lars Markusson, + 46 (0) 70 568 90 31, [email protected] ADRESS Sveriges Olympiska Kommitté, Olympiastadion, Sofiatornet, 114 33 Stockholm TEL 08-402 68 00 www.sok.se LAYOUT Linda Sandgren, SOK TRYCK Elanders MEDIA GUIDE - SWEDISH OLYMPIC TEAM, TOKYO 2020 5 CONTENT SWEDISH OLYMPIC COMMITTEE 6 INTERNATIONAL OLYMPIC MOVEMENT 8 SWEDEN AND THE OLYMPIC GAMES 9 SWEDISH MEDALLISTS 10 CDM:S AND FLAG BEARERS 24 SWEDEN AT PREVIOUS OLYMPIC GAMES 25 OLYMPIC VENUES 26 COMPETITION SCHEDULE 28 SWEDISH OLYMPIC TEAM 32 SWEDISH MEDIA 71 MEDIA GUIDE - SWEDISH OLYMPIC TEAM, TOKYO 2020 6 SWEDISH OLYMPIC COMMITTEE Executive board The executive board, implementing the SOC pro- gramme, meets 8-10 times a year. -

Men's 100M Diamond Discipline 13.07.2021

Men's 100m Diamond Discipline 13.07.2021 Start list 100m Time: 19:25 Records Lane Athlete Nat NR PB SB 1 Isiah YOUNG USA 9.69 9.89 9.89 WR 9.58 Usain BOLT JAM Olympiastadion, Berlin 16.08.09 2 Chijindu UJAH GBR 9.87 9.96 10.03 AR 9.86 Francis OBIKWELU POR Olympic Stadium, Athina 22.08.04 3André DE GRASSECAN9.849.909.99=AR 9.86 Jimmy VICAUT FRA Paris 04.07.15 =AR 9.86 Jimmy VICAUT FRA Montreuil-sous-Bois 07.06.16 4 Trayvon BROMELL USA 9.69 9.77 9.77 NR 9.87 Linford CHRISTIE GBR Stuttgart 15.08.93 5Fred KERLEYUSA9.699.869.86WJR 9.97 Trayvon BROMELL USA Eugene, OR 13.06.14 6Zharnel HUGHESGBR9.879.9110.06MR 9.78 Tyson GAY USA 13.08.10 7 Michael RODGERS USA 9.69 9.85 10.00 DLR 9.69 Yohan BLAKE JAM Lausanne 23.08.12 8Adam GEMILIGBR9.879.9710.14SB 9.77 Trayvon BROMELL USA Miramar, FL 05.06.21 2021 World Outdoor list Medal Winners Road To The Final 9.77 +1.5 Trayvon BROMELL USA Miramar, FL (USA) 05.06.21 1Ronnie BAKER (USA) 16 9.84 +1.2 Akani SIMBINE RSA Székesfehérvár (HUN) 06.07.21 2019 - IAAF World Ch. in Athletics 2 Akani SIMBINE (RSA) 15 9.85 +1.5 Marvin BRACY USA Miramar, FL (USA) 05.06.21 1. Christian COLEMAN (USA) 9.76 3 Lamont Marcell JACOBS (ITA) 13 9.85 +0.8 Ronnie BAKER USA Eugene, OR (USA) 20.06.21 2. -

Praha Indoor 2014

Praha Indoor 2014 O2 Arena, February 25 2014 RESULT LIST Triple Jump Men RESULT NAME COUNTRY DATE VENUE WR 17.92 Teddy Tamgho FRA 6 Mar 2011 Paris-Bercy (Palais Omnisports) WL 17.30 Marian Oprea ROU 15 Feb 2014 Bucuresti NR 17.23 Ján Čado CZE 2 Mar 1985 Athínai TEMPERATURE HUMIDITY START TIME 18:50 - - February 25 2014 END TIME 20:01 - - PLACE BIB NAME COUNTRY DATE of BIRTH ORDER RESULT POINTS 1 2 3 4 5 6 30 Jun 93 7 WL 1 12 Pedro Pablo Pichardo CUB 17.32 MR 16.90 16.33 16.68 17.32 - - 2 13 Ernesto Revé CUB 26 Feb 92 5 17.05 PB 16.31 17.05 X X X X 3 85 Marian Oprea ROU 6 Jun 82 6 16.68 X X 16.27 16.68 X X 4 4 Adrian Świderski POL 27 Sep 86 2 16.07 15.42 X 16.07 X X X 5 65 Julian Reid GBR 23 Sep 88 3 16.06 X 15.70 X 15.53 15.86 16.06 6 71 Shuo Cao CHN 8 Oct 91 4 16.05 SB 15.35 15.31 15.98 X 16.05 13.49 7 98 Alexander Hochuli SUI 19 Jan 84 1 15.45 X 15.19 X 15.45 X 15.35 ALL-TIME TOP LIST 2014 TOP LIST RESULT NAME VENUE DATE RESULT NAME VENUE DATE 17.92 Teddy Tamgho (FRA) Paris-Bercy (Palais 6 Mar 2011 17.30 Marian Oprea (ROU) Bucuresti 15 Feb 17.83 Aliecer Urrutia (CUB) Sindelfingen 1 Mar 1997 17.15 A Chris Carter (USA) Albuquerque (ABQ 23 Feb 17.83 Christian Olsson (SWE) Budapest (SA) 7 Mar 2004 17.04 Will Claye (USA) New York (Armory), NY 25 Jan 17.77 Leonid Voloshin (RUS) Grenoble 6 Feb 1994 17.00 Lyukman Adams (RUS) Mogilev 21 Feb 17.76 Mike Conley (USA) New York, NY 27 Feb 1987 16.99 A Chris Benard (USA) Albuquerque (ABQ 23 Feb 17.75 Phillips Idowu (GBR) Valencia, ESP 9 Mar 2008 16.87 Julian Reid (GBR) Sheffield 8 Feb 17.74 Marian Oprea (ROU) Bucuresti 18 Feb 2006 16.84 A Troy Doris (USA) Albuquerque (ABQ 23 Feb 17.73 Walter Davis (USA) Moskva (Olimpiyskiy 12 Mar 2006 16.80 Gaëtan Saku Bafuanga Baya (FRA) Eaubonne 9 Feb 17.73 Fabrizio Donato (ITA) Paris-Bercy (Palais 6 Mar 2011 16.78 Fabrizio Schembri (ITA) Ancona (Banca 22 Feb 17.72 Brian Wellman (BER) Barcelona 12 Mar 1995 16.74 Dmitriy Sorokin (RUS) Moskva (CSKA) 18 Feb Timing & Data service by OnlineSystem s.r.o. -

Triple Jumping the JAC Way

Triple Jumping the JAC Way Eli Sunquist Jacksonville Athletic Club Jaxtrack.com Introduction Power ballet. Skipping stone. Bouncing ball. Adult hopscotch. The best way to injure your knees and back. One of the most dangerous events in track and field. These are all things that have been said about the triple jump. The triple jump is such an exciting event to watch when done properly. Athletes sprint down a runway at full speed, slowly gliding through the air only to briefly touch down a few times on their way to splashing down into a sandpit. Great jumpers have talked about the event like they are “stones, skipping across the water.” At the highest of levels it looks as if the jumper is walking on air. At the lowest of levels, it looks like someone’s hips are going to pop off, and you just hope they can make it into the sand pit! When done properly you feel like you are flying. When done improperly, you feel like you have been in a car wreck. This, my friends, is the triple jump. I was drawn to the triple jump as a middle schooler who was watching the 1996 Olympic Games on TV, and I happened to see Kenny Harrison triple jump. I was in shock. It looked like he was walking on the air. Although I never looked like him while jumping, that moment of watching him jump got me hooked on the event. The mix of speed, power, technique and balance make the triple jump one of the most exciting events to watch, and any athlete who is dedicated to getting better and doesn’t mind some hard work are the perfect candidates for this event. -

Fraser-Pryce Wins Gold in Doha

SPORT PAGE | 06 PAGE | 08 Lewis Hamilton World Champion wins in Russia Coleman shows to foil Ferrari who’s the renaissance sprint king Monday 30 September 2019 1 Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce (JAM) 10.71 WL 2 Dina Asher-Smith (GBR) 10.83 NR 3 Marie-Josée Ta Lou (CIV) 10.90 Jamaica’s Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce 4 Elaine Thompson (JAM) 10.93 celebrates after winning the women’s 100m final at the 2019 IAAF World Athletics 5 Murielle Ahouré (CIV) 11.02 Sb Championships at the Khalifa International 6 Jonielle Smith (JAM) 11.06 Stadium in Doha, yesterday. RIGHT: Fraser-Pryce 7 Teahna Daniels (USA) 11.19 holds her son Zyon after the race. WOMEN'S 100 METRES FINAL Fraser-Pryce wins gold in Doha ARMSTRONG VAS THE PENINSULA Felix overcomes Bolt as USA rewrite record books Taylor marks Sprint legend Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce of Jamaica yesterday won the women’s 100m title in emphatic hat-trick of fashion. It was her’s fourth 100m world title and eighth overall. triple jump The ‘Pocket Rocket’ crossed the finish line in 10.71 secs – the fastest time in the world this year, sending the Jamaican supporters into a celebration world titles mood. European champion Dina Asher-Smith, who FAWAD HUSSAIN made history by becoming the first British woman THE PENINUSLA to reach a world championship 100m final, clocked 10.83, with Marie Josee Ta Lou of Ivory American star Christian Taylor Coast got the bronze in 10.90. bagged his third straight men’s triple Earlier, United States quartet of Wilbert London, jump title at the IAAF World Athletics Allyson Felix, Courtney Okolo and Michael Cherry Championships after bouncing back won gold in the mixed 4x400m while setting a new from a shaky start at the Khalifa Inter- record, following up their world record in the heats national Stadium yesterday. -

Triple Jump Shot

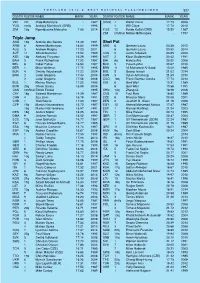

PORTLAND 2016 BEST NATIONAL PLACINGS/MEN 327 COUNTRY POSITION NAME MARK YEAR COUNTRY POSITION NAME MARK YEAR VIN nm Orde Ballantyne - 1987 (USA) 1 Walter Davis 17.73 2006 YUG nm/q Andreja Marinković (SRB) - 1995 1 Will Claye 17.70 2012 ZIM 13q Ngonidzashe Makusha 7.85 2014 YUG 12 Đorđe Kožul (CRO) 15.59 1987 ZIM nm/final Ndabe Mdhlongwa - 1997 Triple Jump ANG 19q António dos Santos 15.49 1991 Shot Put ARM 6 Armen Martirosyan 16.83 1999 ARG 6 Germán Lauro 20.38 2012 AUS 3 Andrew Murphy 17.20 2001 6 Germán Lauro 20.50 2014 AUT 11 Alfred Stummer 15.93 1989 AUS 5 Justin Anlezark 20.65 2003 AZE 16q Aleksey Fatyanov 16.29 1995 AUT 2 Klaus Bodenmüller 20.42 1991 BAH 3 Frank Rutherford 17.02 1987 BIH 8q Hamza Alić 20.00 2008 BEL 8 Didier Falise 16.53 1987 BLR 5 Pavel Lyzhin 20.67 2010 BER 1 Brian Wellman 17.72 1995 BRN 11 Ali Mohamed Al-Saad 15.02 1985 BLR 4 Dmitriy Valyukevich 17.22 2004 BUL 5 Georgi Ivanov 21.02 2014 BRA 2 Jadel Gregório 17.43 2004 CAN 3 Dylan Armstrong 21.39 2010 2 Jadel Gregório 17.56 2006 CGO 18q Frank Elemba Owaka 17.74 2014 BUL 1 Khristo Markov 17.22 1985 CHI 6 Gert Weil 19.91 1989 BUR 20q Olivier Sanou 16.09 2004 6 Gert Weil 19.56 1991 CAN nm/final Edrick Floréal - 1995 CHN 14q Zhang Qi 18.96 2006 CAY 18q Edward Manderson 14.39 1987 CUB 10 Paul Ruíz 18.80 1989 CHN 4 Zou Sixin 16.78 1991 CZE 6 Miroslav Menc 20.08 2001 CUB 1 Yoel García 17.30 1997 DEN 2 Joachim B. -

All Time Men's World Ranking Leader

All Time Men’s World Ranking Leader EVER WONDER WHO the overall best performers have been in our authoritative World Rankings for men, which began with the 1947 season? Stats Editor Jim Rorick has pulled together all kinds of numbers for you, scoring the annual Top 10s on a 10-9-8-7-6-5-4-3-2-1 basis. First, in a by-event compilation, you’ll find the leaders in the categories of Most Points, Most Rankings, Most No. 1s and The Top U.S. Scorers (in the World Rankings, not the U.S. Rankings). Following that are the stats on an all-events basis. All the data is as of the end of the 2019 season, including a significant number of recastings based on the many retests that were carried out on old samples and resulted in doping positives. (as of April 13, 2020) Event-By-Event Tabulations 100 METERS Most Points 1. Carl Lewis 123; 2. Asafa Powell 98; 3. Linford Christie 93; 4. Justin Gatlin 90; 5. Usain Bolt 85; 6. Maurice Greene 69; 7. Dennis Mitchell 65; 8. Frank Fredericks 61; 9. Calvin Smith 58; 10. Valeriy Borzov 57. Most Rankings 1. Lewis 16; 2. Powell 13; 3. Christie 12; 4. tie, Fredericks, Gatlin, Mitchell & Smith 10. Consecutive—Lewis 15. Most No. 1s 1. Lewis 6; 2. tie, Bolt & Greene 5; 4. Gatlin 4; 5. tie, Bob Hayes & Bobby Morrow 3. Consecutive—Greene & Lewis 5. 200 METERS Most Points 1. Frank Fredericks 105; 2. Usain Bolt 103; 3. Pietro Mennea 87; 4. Michael Johnson 81; 5. -

2012 European Championships Statistics – Men's 100M

2012 European Championships Statistics – Men’s 100m by K Ken Nakamura All time performance list at the European Championships Performance Performer Time Wind Name Nat Pos Venue Year 1 1 9.99 1.3 Francis Obikwelu POR 1 Göteborg 20 06 2 2 10.04 0.3 Darren Campbell GBR 1 Budapest 1998 3 10.06 -0.3 Francis Obikwelu 1 München 2002 3 3 10.06 -1.2 Christophe Lemaitre FRA 1sf1 Barcelona 2010 5 4 10.08 0.7 Linford Christie GBR 1qf1 Helsinki 1994 6 10.09 0.3 Linford Christie 1sf1 Sp lit 1990 7 5 10.10 0.3 Dwain Chambers GBR 2 Budapest 1998 7 5 10.10 1.3 Andrey Yepishin RUS 2 Göteborg 2006 7 10.10 -0.1 Dwain Chambers 1sf2 Barcelona 2010 10 10.11 0.5 Darren Campbell 1sf2 Budapest 1998 10 10.11 -1.0 Christophe Lemaitre 1 Barce lona 2010 12 10.12 0.1 Francis Obikwelu 1sf2 München 2002 12 10.12 1.5 Andrey Yepishin 1sf1 Göteborg 2006 14 10.14 -0.5 Linford Christie 1 Helsinki 1994 14 7 10.14 1.5 Ronald Pognon FRA 2sf1 Göteborg 2006 14 7 10.14 1.3 Matic Osovnikar SLO 3 Gö teborg 2006 17 10.15 -0.1 Linford Christie 1 Stuttgart 1986 17 10.15 0.3 Dwain Chambers 1sf1 Budapest 1998 17 10.15 -0.3 Darren Campbell 2 München 2002 20 9 10.16 1.5 Steffen Bringmann GDR 1sf1 Stuttgart 1986 20 10.16 1.3 Ronald Pognon 4 Göteb org 2006 20 9 10.16 1.3 Mark Lewis -Francis GBR 5 Göteborg 2006 20 9 10.16 -0.1 Jaysuma Saidy Ndure NOR 2sf2 Barcelona 2010 24 12 10.17 0.3 Haralabos Papadias GRE 3 Budapest 1998 24 12 10.17 -1.2 Emanuele Di Gregorio IA 2sf1 Barcelona 2010 26 14 10.18 1.5 Bruno Marie -Rose FRA 2sf1 Stuttgart 1986 26 10.18 -1.0 Mark Lewis Francis 2 Barcelona 2010 -

Key Officers List (UNCLASSIFIED)

United States Department of State Telephone Directory This customized report includes the following section(s): Key Officers List (UNCLASSIFIED) 9/13/2021 Provided by Global Information Services, A/GIS Cover UNCLASSIFIED Key Officers of Foreign Service Posts Afghanistan FMO Inna Rotenberg ICASS Chair CDR David Millner IMO Cem Asci KABUL (E) Great Massoud Road, (VoIP, US-based) 301-490-1042, Fax No working Fax, INMARSAT Tel 011-873-761-837-725, ISO Aaron Smith Workweek: Saturday - Thursday 0800-1630, Website: https://af.usembassy.gov/ Algeria Officer Name DCM OMS Melisa Woolfolk ALGIERS (E) 5, Chemin Cheikh Bachir Ibrahimi, +213 (770) 08- ALT DIR Tina Dooley-Jones 2000, Fax +213 (23) 47-1781, Workweek: Sun - Thurs 08:00-17:00, CM OMS Bonnie Anglov Website: https://dz.usembassy.gov/ Co-CLO Lilliana Gonzalez Officer Name FM Michael Itinger DCM OMS Allie Hutton HRO Geoff Nyhart FCS Michele Smith INL Patrick Tanimura FM David Treleaven LEGAT James Bolden HRO TDY Ellen Langston MGT Ben Dille MGT Kristin Rockwood POL/ECON Richard Reiter MLO/ODC Andrew Bergman SDO/DATT COL Erik Bauer POL/ECON Roselyn Ramos TREAS Julie Malec SDO/DATT Christopher D'Amico AMB Chargé Ross L Wilson AMB Chargé Gautam Rana CG Ben Ousley Naseman CON Jeffrey Gringer DCM Ian McCary DCM Acting DCM Eric Barbee PAO Daniel Mattern PAO Eric Barbee GSO GSO William Hunt GSO TDY Neil Richter RSO Fernando Matus RSO Gregg Geerdes CLO Christine Peterson AGR Justina Torry DEA Edward (Joe) Kipp CLO Ikram McRiffey FMO Maureen Danzot FMO Aamer Khan IMO Jaime Scarpatti ICASS Chair Jeffrey Gringer IMO Daniel Sweet Albania Angola TIRANA (E) Rruga Stavro Vinjau 14, +355-4-224-7285, Fax +355-4- 223-2222, Workweek: Monday-Friday, 8:00am-4:30 pm. -

START LIST Triple Jump Men - Final

Daegu (KOR) World Championships 27 August - 4 September 2011 START LIST Triple Jump Men - Final 04 SEP 2011 - 19:05 RESULT WIND NAME AGE VENUE DATE World Record 18.29 +1.3 Jonathan EDWARDS (GBR) 29 Göteborg 7 Aug 95 Championships Record 18.29 +1.3 Jonathan EDWARDS (GBR) 29 Göteborg 7 Aug 95 World Leading 17.91 +1.4 Teddy TAMGHO (FRA) 22 Lausanne 30 Jun 11 ORDER BIB NAME COUNTRY DATE OF BIRTH PERSONAL BEST SEASON BEST 1 853 Nelson ÉVORA POR 20 APR 84 17.74 17.31 넬슨 에보라 1984년 4월 20일 2 161 Leevan SANDS BAH 16 AUG 81 17.59 17.13 리반 샌즈 1981년 8월 16일 3 572 Fabrizio DONATO ITA 14 AUG 76 17.73 i 17.73 i 파브리지오 도나토 1976년 8월 14일 4 404 Benjamin COMPAORÉ FRA 5 AUG 87 17.29 17.29 벤자민 콤파오레 1987년 8월 5일 5 130 Henry FRAYNE AUS 14 APR 90 17.04 17.04 헨리 프레인 1990년 4월 14일 6 982 Christian OLSSON SWE 25 JAN 80 17.83 i 17.29 크리스천 올손 1980년 1월 25일 7 1045 Sheryf EL-SHERYF UKR 2 JAN 89 17.72 17.72 셰리프 엘-셰리프 1989년 1월 2일 8 1069 Will CLAYE USA 13 JUN 91 17.35 17.35 윌 클레이 1991년 6월 13일 9 442 Phillips IDOWU GBR 30 DEC 78 17.81 17.59 필립스 이도우 1978년 12월 30일 10 1127 Christian TAYLOR USA 18 JUN 90 17.68 17.68 크리스천 테일러 1990년 6월 18일 11 279 Alexis COPELLO CUB 12 AUG 85 17.68 17.68 알렉시스 코폐요 1985년 8월 12일 12 275 Yoandris BETANZOS CUB 15 FEB 82 17.69 i 17.23 요안드리스 베탄조스 1982년 2월 15일 ALL-TIME TOP LIST SEASON TOP LIST 18.29 +1.3 Jonathan EDWARDS (GBR) Göteborg 7 Aug 95 17.91 +1.4 Teddy TAMGHO (FRA) Lausanne 30 Jun 11 18.09 -0.4 Kenny HARRISON (USA) Atlanta, GA 27 Jul 96 17.72 +1.3 Sheryf EL-SHERYF (UKR) Ostrava 17 Jul 11 17.98 +1.2 Teddy TAMGHO (FRA) New York City, NY 12 Jun 10 17.68 -

Men's 100M Diamond Discipline - Heat 1 20.07.2019

Men's 100m Diamond Discipline - Heat 1 20.07.2019 Start list 100m Time: 14:35 Records Lane Athlete Nat NR PB SB 1 Julian FORTE JAM 9.58 9.91 10.17 WR 9.58 Usain BOLT JAM Berlin 16.08.09 2 Adam GEMILI GBR 9.87 9.97 10.11 AR 9.86 Francis OBIKWELU POR Athina 22.08.04 3 Yuki KOIKE JPN 9.97 10.04 10.04 =AR 9.86 Jimmy VICAUT FRA Paris 04.07.15 =AR 9.86 Jimmy VICAUT FRA Montreuil-sous-Bois 07.06.16 4 Arthur CISSÉ CIV 9.94 9.94 10.01 NR 9.87 Linford CHRISTIE GBR Stuttgart 15.08.93 5 Yohan BLAKE JAM 9.58 9.69 9.96 WJR 9.97 Trayvon BROMELL USA Eugene, OR 13.06.14 6 Akani SIMBINE RSA 9.89 9.89 9.95 MR 9.78 Tyson GAY USA 13.08.10 7 Andrew ROBERTSON GBR 9.87 10.10 10.17 DLR 9.69 Yohan BLAKE JAM Lausanne 23.08.12 8 Oliver BROMBY GBR 9.87 10.22 10.22 SB 9.81 Christian COLEMAN USA Palo Alto, CA 30.06.19 9 Ojie EDOBURUN GBR 9.87 10.04 10.17 2019 World Outdoor list 9.81 -0.1 Christian COLEMAN USA Palo Alto, CA 30.06.19 Medal Winners Road To The Final 9.86 +0.9 Noah LYLES USA Shanghai 18.05.19 1 Christian COLEMAN (USA) 23 9.86 +0.8 Divine ODUDURU NGR Austin, TX 07.06.19 2018 - Berlin European Ch. -

World Rankings — Men’S Triple Jump 1947 Christian Taylor Has Been 1

World Rankings — Men’s Triple Jump 1947 Christian Taylor has been 1 .................... Lennart Moberg (Sweden) 2 .................. Geraldo de Oliveira (Brazil) No. 1 for 8 of the last 9 3 ..........................Arne Åhman (Sweden) years, and 6 in a row 4 ....................Valdemar Rautio (Finland) 5 ......................... Åke Hallgren (Sweden) 6 .................... Bertil Johnsson (Sweden) 7 ................................ Carlos Vera (Chile) 8 ......................... Lloyd Miller (Australia) 9 ...................... George Avery (Australia) 10 .................... Keizo Hasegawa (Japan) 1948 1 ...................... Keizo Hasegawa (Japan) 2 ..........................Arne Åhman (Sweden) 3 ...................... George Avery (Australia) 4 .................. Geraldo de Oliveira (Brazil) 5 ............................ Henry Rebello (India) 6 .................... Lennart Moberg (Sweden) 7 ............................ Ruhi Sarıalp (Turkey) 8 .................... Preben Larsen (Denmark) 9 ...................... Les McKeand (Australia) 10 ..................Valdemar Rautio (Finland) 1949 1 ..........................Arne Åhman (Sweden) 2 ....Leonid Shcherbakov (Soviet Union) 3 ........................... Hélio da Silva (Brazil) 4 .................... Lennart Moberg (Sweden) 5 ..........................Wakaki Maeda (Japan) 6 .................. Geraldo de Oliveira (Brazil) 7 .................Kichigoro Fujihashi (Japan) 8 ....................Valdemar Rautio (Finland) 9 .....................Adhemar da Silva (Brazil) 10 ...................