The Importance of Being Earnest by Oscar Wilde

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

September 6, 2011 (XXIII:2) Anthony Asquith and Leslie Howard, PYGMALION (1938, 96 Min)

September 6, 2011 (XXIII:2) Anthony Asquith and Leslie Howard, PYGMALION (1938, 96 min) Directed by Anthony Asquith and Leslie Howard Written by George Bernard Shaw (play, scenario & dialogue), W.P. Lipscomb, Cecil Lewis, Ian Dalrymple (uncredited), Anatole de Grunwald (uncredited), Kay Walsh (uncredited) Produced by Gabriel Pascal Original Music by Arthur Honegger Cinematography by Harry Stradling Edited by David Lean Art Direction by John Bryan Costume Design by Ladislaw Czettel (as Professor L. Czettel), Schiaparelli (uncredited), Worth (uncredited) Music composed by William Axt Music conducted by Louis Levy Leslie Howard...Professor Henry Higgins Wendy Hiller...Eliza Doolittle Wilfrid Lawson...Alfred Doolittle Marie Lohr...Mrs. Higgins Scott Sunderland...Colonel George Pickering GEORGE BERNARD SHAW [from Wikipedia](26 July 1856 – 2 Jean Cadell...Mrs. Pearce November 1950) was an Irish playwright and a co-founder of the David Tree...Freddy Eynsford-Hill London School of Economics. Although his first profitable writing Everley Gregg...Mrs. Eynsford-Hill was music and literary criticism, in which capacity he wrote many Leueen MacGrath...Clara Eynsford Hill highly articulate pieces of journalism, his main talent was for Esme Percy...Count Aristid Karpathy drama, and he wrote more than 60 plays. Nearly all his writings address prevailing social problems, but have a vein of comedy Academy Award – 1939 – Best Screenplay which makes their stark themes more palatable. Shaw examined George Bernard Shaw, W.P. Lipscomb, Cecil Lewis, Ian Dalrymple education, marriage, religion, government, health care, and class privilege. ANTHONY ASQUITH (November 9, 1902, London, England, UK – He was most angered by what he perceived as the February 20, 1968, Marylebone, London, England, UK) directed 43 exploitation of the working class. -

The North of England in British Wartime Film, 1941 to 1946. Alan

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CLoK The North of England in British Wartime Film, 1941 to 1946. Alan Hughes, University of Central Lancashire The North of England is a place-myth as much as a material reality. Conceptually it exists as the location where the economic, political, sociological, as well as climatological and geomorphological, phenomena particular to the region are reified into a set of socio-cultural qualities that serve to define it as different to conceptualisations of England and ‘Englishness’. Whilst the abstract nature of such a construction means that the geographical boundaries of the North are implicitly ill-defined, for ease of reference, and to maintain objectivity in defining individual texts as Northern films, this paper will adhere to the notion of a ‘seven county North’ (i.e. the pre-1974 counties of Cumberland, Westmorland, Northumberland, County Durham, Lancashire, Yorkshire, and Cheshire) that is increasingly being used as the geographical template for the North of England within social and cultural history.1 The British film industry in 1941 As 1940 drew to a close in Britain any memories of the phoney war of the spring of that year were likely to seem but distant recollections of a bygone age long dispersed by the brutal realities of the conflict. Outside of the immediate theatres of conflict the domestic industries that had catered for the demands of an increasingly affluent and consuming population were orientated towards the needs of a war economy as plant, machinery, and labour shifted into war production. -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

Shail, Robert, British Film Directors

BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS INTERNATIONAL FILM DIRECTOrs Series Editor: Robert Shail This series of reference guides covers the key film directors of a particular nation or continent. Each volume introduces the work of 100 contemporary and historically important figures, with entries arranged in alphabetical order as an A–Z. The Introduction to each volume sets out the existing context in relation to the study of the national cinema in question, and the place of the film director within the given production/cultural context. Each entry includes both a select bibliography and a complete filmography, and an index of film titles is provided for easy cross-referencing. BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS A CRITI Robert Shail British national cinema has produced an exceptional track record of innovative, ca creative and internationally recognised filmmakers, amongst them Alfred Hitchcock, Michael Powell and David Lean. This tradition continues today with L GUIDE the work of directors as diverse as Neil Jordan, Stephen Frears, Mike Leigh and Ken Loach. This concise, authoritative volume analyses critically the work of 100 British directors, from the innovators of the silent period to contemporary auteurs. An introduction places the individual entries in context and examines the role and status of the director within British film production. Balancing academic rigour ROBE with accessibility, British Film Directors provides an indispensable reference source for film students at all levels, as well as for the general cinema enthusiast. R Key Features T SHAIL • A complete list of each director’s British feature films • Suggested further reading on each filmmaker • A comprehensive career overview, including biographical information and an assessment of the director’s current critical standing Robert Shail is a Lecturer in Film Studies at the University of Wales Lampeter. -

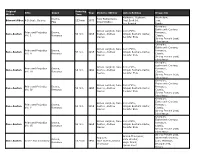

Original Writer Title Genre Running Time Year Director/Writer Actor

Original Running Title Genre Year Director/Writer Actor/Actress Keywords Writer Time Katharine Hepburn, Alcoholism, Drama, Tony Richardson; Edward Albee A Delicate Balance 133 min 1973 Paul Scofield, Loss, Play Edward Albee Lee Remick Family Georgian, Eighteenth Century, Simon Langton; Jane Colin Firth, Pride and Prejudice Drama, Romance, Jane Austen 53 min 1995 Austen, Andrew Crispin Bonham-Carter, Vol. I Romance Classic, Davies Jennifer Ehle Strong Female Lead, Inheritance Georgian, Eighteenth Century, Simon Langton; Jane Colin Firth, Pride and Prejudice Drama, Romance, Jane Austen 54 min 1995 Austen, Andrew Crispin Bonham-Carter, Vol. II Romance Classic, Davies Jennifer Ehle Strong Female Lead, Inheritance Georgian, Eighteenth Century, Simon Langton; Jane Colin Firth, Pride and Prejudice Drama, Romance, Jane Austen 53 min 1995 Austen, Andrew Crispin Bonham-Carter, Vol. III Romance Classic, Davies Jennifer Ehle Strong Female Lead, Inheritance Georgian, Eighteenth Century, Simon Langton; Jane Colin Firth, Pride and Prejudice Drama, Romance, Jane Austen 53 min 1995 Austen, Andrew Crispin Bonham-Carter, Vol. IV Romance Classic, Davies Jennifer Ehle Strong Female Lead, Inheritance Georgian, Eighteenth Century, Simon Langton; Jane Colin Firth, Pride and Prejudice Drama, Romance, Jane Austen 50 min 1995 Austen, Andrew Crispin Bonham-Carter, Vol. V Romance Classic, Davies Jennifer Ehle Strong Female Lead, Inheritance Georgian, Eighteenth Century, Simon Langton; Jane Colin Firth, Pride and Prejudice Drama, Romance, Jane Austen 52 min 1995 Austen, -

ASQUITH, Raymond

Research Page 1 Name: Lieut Raymond ASQUITH 3rd Grenadier Guards Age Parents: Right Hon. Herbert Henry ASQUITH K.C., M.P., Prime Minister (born 12 Sep 1852 in Morley, YKS, ENG - died 15 Feb 1928) and Helen Kelsall MELLAND (born Dec Qu. 1854 in Rochdale, Lancashire - died in Dec 1891) 37 Life Range 6 Nov 1878- 15 Sep 1916 -26 12 Sep 1852 Birth of Father: Right Hon. Herbert Henry ASQUITH K.C., M.P., Prime Minister (born 12 Sep 1852 in Morley, YKS, ENG - died 15 Feb 1928). In Morley, YKS, ENG. -24 Dec Qu. 1854 Birth of Mother: Helen Kelsall MELLAND (born Dec Qu. 1854 in Rochdale, Lancashire - died in Dec 1891). In Rochdale, Lancashire. 0 6 Nov 1878 Birth: Hampstead, MDX, ENG. 3 1881 Census: Hampstead, MDX, ENG. At 12 John Street: Herbert Henry ASQUITH, 28, Barrister (in practice) BA Oxford, born Morley, Yorkshire Helen Kelsall, 26, born Rochdale, Lancashire Raymond, 2, born Hampstead, Middlesex Gilbert (Herbert?), under 1 month, born Hampstead, Middlesex [Plus a visitor (Nurse) & 3 servants] ~8 Abt 1886 Birth of Spouse: Katharine Frances HORNER (born about 1886 in London, ENG - died in 1976 in SOM, ENG). 13 1891 Mother: Dead. 13 1891 Census: Winkfield, Berkshire. At Lambrook School, Winkfield Row: Raymond ASQUITH, boarder, 12, pupil, born Hampstead Parents: 27 Mansfield Gardens, Hampstead Herbert H., 38, Barrister QC MP, born Morley, Yorkshire Helen K., 36, born Rochdale, Lancashire Herbert, 10, born Hampstead Arthur M., 7, born Hampstead Helen V., 3, born Hampstead Cyril, 1, born Hampstead (Plus a Governess & 4 Servants) 13 1891 School: Lambrook School. -

© in This Web Service Cambridge University

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-00101-5 - Modern British Drama on Screen Edited by R. Barton Palmer and William Robert Bray Index More information Index 1914 (book), 14 Ayckbourn, Alan, 4 1984 (novel, 1949), 270 Azenberg, Emanuel, 86 49th Parallel, The (Michael Powell, 1925), 46 Baird, Teddy, 240 Balcon, Michael, 12, 89 Absurd Person Singular (play, 1972), 4 Bardolatry, 6 Acapulco, 114 Barker, Harvey Granville, 7 Aeschylus, 66 Barnes, Clive, 266 Agamemnon (play), 66 Barnett, Samuel, 265 Agate, James, 18 Barrie, J. M., 3 Aldgate, Anthony, 10 Barry, Gerald, 230 Alexandroff, Grigori, 18 Barthes, Roland, 251 Alfie (Lewis Gilbert, 1966), 178 Battersea, 54 All Quiet on the Western Front (Lewis Milestone, Battersea Park, 56 1930), 12, 28 Bazin, André, 9, 96, 130 Allsop, Kenneth, 103 BBC, the, 18 Anderson, Lindsay, 71, 87 Beaverbrook, Max, 45 Andrew, Dudley, 141, 194 Beckett, Samuel, 63 Angel of the North (sculpture, 1998), 178 Bennett, Alan, 9, 258 Angels in America, Part One: Millennium Bennett, Susan, 123 Approaches (book, 1993), 261 Berger, John, 182 Angels One Five (George More O’Ferrall, 1952), Berlin, 16 87, 99 Beyond the Fringe (play, 1960), 258 Angry Young Men Dramas, 63 BFI, the, 23 “Annus Mirabilis,” 161 Big Ben, 57 anti-Aristotelianism, 3 Billington, Michael, 266 Apartment, The (Billy Wilder, 1960), 55 Billy Liar (John Schlesinger, Apollo Theatre, The, 15 1963), 127 Arad, Ron, 176 Biograph, 6 Armistice Day, 23 Black, Edward, 69 Arnold, Matthew, 5, 80 Blackfriars Bridge, 57 Artaudian Theatre of Cruelty, 3 Blackmail (Alfred Hitchcock, -

ANTHONY ASQUITH on BROADCASTING FILMS E IRE Edited by NORMAN EDWARDS Vol

ANTHONY ASQUITH ON BROADCASTING FILMS E IRE Edited by NORMAN EDWARDS Vol. XI. No. 26. FEBRUARY, 1929. My Programme - - By Rosita Forbes The" Neutro- Screen "Three The " Instanto " Two Radio and the Gramophone Supplement etc., etc., etc. MODERN WIRELESS February, 1929 In a recent Cape to Cairo and London car endurance test Mullard Valves were unhesitatingly chosenforthe radio installation in the car. A seven months' journey - over mountains, through rivers, across some of the roughest country in the world-andnotasinglevalve breakage or replacement during the whole journey. Mullard Valves were chosen because experience had proved their relia- bility; this severe test again con- firmedtheirsupremacy. Under the most adverse conditions the travellers were ableto maintain communication and to enjoy the B.B.C. programmes in their lonely camps. Use Mullard Valves in your receiver. Use them for reliability, for strength, for tone, volume and distance. MullardTHE -MASTER-VALVE ADVT. THE MULLARD WIRELESS SERVICE CO., LTDMULLARD HOUSE, DENMARK STREET, LONDON, W.C.2. Arks February, 1929 MODERN WIRELESS CONTENT VOL. XI.No. 26. MODERN WIRELESS. FEBRUARY, 1929. Page Page 161 Editorial . 119 Kalundborg's Companion . .. 163 On the Short Waves . 120 Grid -Circuit Coupling Broadcasting Films - Will it Come to The New Pentodes .. ..165 That? .. How Time Flies in Radio .. 167 The " Neuiro-Screen "Three' 123 A Versatile Meter 169 An H.F. Fault -Finder 129 Short -Wave Schedules 172 Finding Foreigners .. 131 Aerials Abroad .. 173 The " M.W." Tapped Crystal Set 133 Mixing Battery Acid . 176 " 6 L T " Crystal Amplifiers .. 177 B.B.C. Progress in 1923 139 Generating GiganticH.T. -

The Importance of Being Earnest on Stage and Screen. an Analysis of the Last Oscar Wilde’S Play

Master’s Degree Programme In European, American and Postcolonial Language and Literature “Second Cycle (D.M. 270/2004)” Final Thesis The Importance of Being Earnest on Stage and Screen. An analysis of the last Oscar Wilde’s play. Supervisor Ch. Prof.ssa Michela VANON ALLIATA Assistant supervisor Ch. Prof. Shaul BASSI Graduand Veronica RIZZI 866200 Academic Year 2017/18 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 3 CHAPTER ONE 5 1. THE PICTURE OF OSCAR WILDE. 5 1.1. Life. 5 1.2. Oxford. 7 1.3. Rome and Greece. 8 1.4. Advances and Marriage. 9 1.5. Lord Alfred. 12 1.6. Prison. 15 1.7. Decline. 16 CHAPTER TWO 18 2. THE IMPORTANCE OF BEING EARNEST. 18 2.1. The Play. 18 2.2. The Genesis of the comedy. 24 2.3. First Publication. 27 2.4. Society and Marriage. 34 2.5. Satiric Strategy. 39 1 CHAPTER THREE 44 3. THE IMPORTANCE OF SCREEN. 44 3.1. The advent of cinema. 44 3.2. Cinematographic Adaptation. 47 3.3. Anthony Asquith’s adaptation of The Importance of Being Earnest. 51 CHAPTER FOUR 79 4. WILDE ON SCREEN. 79 4.1. The Gaze of Contemporary Cinema. 79 4.2. Oliver Parker’s adaptation of The Importance of Being Earnest. 80 CONCLUSIONS 110 BIBLIOGRAPHY 112 2 INTRODUCTION The Importance of Being Earnest (1895) is one of the most significant comedies written by Oscar Wilde before his downfall. It is a comedy of manners which mocks the world and values of Victorian upper-middle class society, by showing them to be snobbish and dishonest. -

National Gallery of Art

ADMISSION IS FREE DIRECTIONS 10:00 TO 5:00 National Gallery of Art Release Date: December 19, 2017 National Gallery of Art 2018 Winter Film Program Features Restorations, Premieres, International Shorts, Retrospectives, Gems from the British Film Institute, a Focus on Jackson Pollock, and Special Appearances by Ten Filmmakers and Artists Film still from The Sacrifice (Andrei Tarkovsky, 1986, subtitles, 149 minutes), Washington premiere of the restoration to be shown at the National Gallery of Art on Sunday, March 18, at 4:00 p.m. Image courtesy Kino Lorber. Washington, DC—The 2018 winter film program for the National Gallery of Art presents many opportunities in January, February, and March for visitors to enjoy American and Washington premieres, new film series, restorations of films and media art works on the big screen, film shorts, and ciné-concerts. Films are shown in the East Building Auditorium in original formats whenever possible. Seating is on a first-come, first-seated basis unless noted otherwise. Doors open 30 minutes before films begin. Films are subject to change on short notice. For up-to-date information, visit nga.gov/film. Film series include Affinities, or The Weight of Cinema (January 6–14), an eight-part series that brings together short films from international makers with those of noted American film artist Kevin Jerome Everson and writer Greg de Cuir Jr., introduced by visiting artists: Kelly Gallagher introduces An Affinity for the Interval; Akosua Adoma Owusu introduces An Affinity for Labor; and other Affinities films are introduced by Margaret Rorison, Christopher Harris, Cauleen Smith, and Dirk de Bruyn. -

Reginald Mckenna British Politics and Society

Reginald McKenna British Politics and Society PETER CATTERALL, Series Editor The Making of Channel 4 Mass Conservatism Edited by Peter Catterall The Conservatives and the Public since the 1880s Managing Domestic Dissent in First Edited by Stuart Ball and Ian Holliday World War Britain Brock Millman Defining British Citizenship Empire, Commonwealth and Modern Reforming the Constitution Britain Debates in Twentieth Century Britain Rieko Karatani Edited by Peter Catterall, Wolfram Kaiser and Ulrike Walton-Jordan Television Policies of the Labour Party 1951-2001 Pessimism and British War Policy, Des Freedman 1916-1918 Brock Millman Creating the National Health Service Aneurin Bevan and the Medical Lords Amateurs and Professionals in Marvin Rintala Post-War British Sport Edited by Adrian Smith and Dilwyn A Social History of Milton Keynes Porter Middle England/Edge City Mark Clapson A Life of Sir John Eldon Gorst Disraeli's Awkward Disciple Scottish Nationalism and the Idea of Archie Hunter Europe Concepts of Europe and the Nation Conservative Party Attitudes to Atsuko Ichijo Jews 1900-1950 Harry Defries The Royal Navy in the Falklands Conflict and the Gulf War Poor Health Culture and Strategy Social Inequality before and after the Alastair Finlan Black Report Edited by Virginia Berridge and Stuart The Labour Party in Opposition Blume 1970-1974 Patrick Bell The Civil Service Commission Reginald McKenna 1855-1991 Financier among Statesmen, 1863- A Bureau Biography 1916 Richard A. Chapman Martin Farr Popular Newspapers, the Labour Party and British Politics James Thomas In the Midst of Events The Foreign Office Diaries and Papers of Kenneth Younger, February 1950- October 1951 Edited by Geoffrey Warner Strangers, Aliens and Asians Huguenots, Jews and Bangladeshis in Spitalfields 1666-2000 Anne J. -

Stanley Kubrick: Producers and Production Companies

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by De Montfort University Open Research Archive Stanley Kubrick: Producers and Production Companies Thesis submitted by James Fenwick In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy De Montfort University, September 2017 1 Abstract This doctoral thesis examines filmmaker Stanley Kubrick’s role as a producer and the impact of the industrial contexts upon the role and his independent production companies. The thesis represents a significant intervention into the understanding of the much-misunderstood role of the producer by exploring how business, management, working relationships and financial contexts influenced Kubrick’s methods as a producer. The thesis also shows how Kubrick contributed to the transformation of industrial practices and the role of the producer in Hollywood, particularly in areas of legal authority, promotion and publicity, and distribution. The thesis also assesses the influence and impact of Kubrick’s methods of producing and the structure of his production companies in the shaping of his own reputation and brand of cinema. The thesis takes a case study approach across four distinct phases of Kubrick’s career. The first is Kubrick’s early years as an independent filmmaker, in which he made two privately funded feature films (1951-1955). The second will be an exploration of the Harris-Kubrick Pictures Corporation and its affiliation with Kirk Douglas’ Bryna Productions (1956-1962). Thirdly, the research will examine Kubrick’s formation of Hawk Films and Polaris Productions in the 1960s (1962-1968), with a deep focus on the latter and the vital role of vice-president of the company.