Property Rights Assessment in Amuru District

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Roco Wat I Acoli

Roco Wat I Acoli Restoring Relationships in Acholi‐land: Traditional Approaches to Justice and Reintegration September, 2005 Liu Institute for Global Issues Gulu District NGO Forum Ker Kwaro Acholi FRONT COVER PHOTOGRAPHY Left: The Oput Root used in the Mato Oput ceremony, Erin Baines Centre: Dancers at a communal cleansing ceremony, Lara Rosenoff Right: A calabash holding the Oput and Kwete brew, Erin Baines BACK COVER PHOTOGRAPHY Background: Winnower for holding the Oput, and knife to slaughter sheep at a Mato Oput Ceremony, Carla Suarez Insert: See above © 2005 ROCO WAT I ACOLI Restoring Relations in Acholi‐land: Traditional Approaches To Reintegration and Justice Supported by: The John D. and Catherine T. Macarthur Foundation The Royal Embassy of the Netherlands Prepared by: Liu Institute for Global Issues Gulu District NGO Forum With the assistance of Ker Kwaro Acholi September, 2005 Comments: [email protected] or Boniface@human‐security‐africa.ca i Roco Wat I Acoli ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The 19 year conflict in northern Uganda has resulted in one of the world’s worst, most forgotten humanitarian crisis: 90 percent of the affected-population in Acholi is confined to internally displaced persons camps, dependant on food assistance. The civilian population is vulnerable to being abducted, beaten, maimed, tortured, raped, violated and murdered on a daily basis. Over 20,000 children have been abducted by the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) and forced into fighting and sexual slavery. Up to 40,000 children commute nightly to sleep in centres of town and avoid abduction. Victims and perpetrators are often the same person, and currently there is no system of accountability for those most responsible for the atrocities. -

NWOYA BFP 2015-16.Pdf

Local Government Budget Framework Paper Vote: 606 Nwoya District Structure of Budget Framework Paper Foreword Executive Summary A: Revenue Performance and Plans B: Summary of Department Performance and Plans by Workplan C: Draft Annual Workplan Outputs for 2015/16 Page 1 Local Government Budget Framework Paper Vote: 606 Nwoya District Foreword Nwoya District Local Government continues to implement decentralized and participatory development planning and budgeting process as stipulated in the Local Government Act CAP 243 under section 36(3). This Local Government Budget Framework Paper outlines district's intended interventions for social and economic development in FY 2015/16. The development budget proposals earmarked in this 2015/16 Budget Framework Paper focus on the following key priority areas of; Increasing household incomes and promoting equity, Enhancing the availability of gainful employment, Enhancing Human capital, Improving livestock and quality of economic infrastructure, Promoting Science, Technology and Innovation (STI) and ICT to enhance competiveness, Increasing access to quality social services, Strengthening good governance, defence and security and Promoting a sustainable population and use of environment and natural resources in a bid to accelerate Prosperity For All. Acquisition of five acrea of land for the construction of Judiciary offices at Anaka T.C. This policy framework indentifies the revenue projections and expenditure allocation priorities. This will form the basis for preparation of detailed estimates of revenue and expenditure that shall be presented and approved by the District Council. In the medium term, the District will be committed to implement its policies and strategies towards achieving its Mission statement "To serve the Community through the coordinated delivery of services which focus on National and Local priorities and contribute to sustainable improvement of the quality of life of the people in the District". -

Marasa Africa Fact Sheet

MARASA AFRICA FACT SHEET PROPERTY ACCOMMODATION GUEST AMENITIES ACCESS CULINARY EXPERIENCE DESTINATION HIGHLIGHTS Paraa Safari • 25 Classic Guest • Free - Form • 337 km Entebbe • Captain’s Table Restaurant • Murchison Falls National Lodge Rooms Swimming pool International Airport • Nile Terrace Restaurant Park • 26 Deluxe Guest with views over the • 20 km Pakuba • Poolside Bar & Terrace • Located on the majestic Rooms Nile River Airfield • Bush Dinning along the Nile River, ‘Home of • 2 Wheelchair • Marasa Africa Spa • 12 km Bugungu shores of the Nile Hippos’ - +256 (0) 312 Friendly Guest & Fitness Centre Airstrip • Sundowner Cruise on the 260 260 Rooms (Included • Signature Pool Bar • 294 km Kampala Nile Delta Classic rooms) • Business Centre • Murchison Falls by Boat or • 2 Suites • Complimentary by Land • 3 Safari Tents Wi-Fi in the lodge • Game Drive Safari • The Queens public areas • Sports Fishing Cottage • Sundowners • Chimpanzee Tracking in and campfires Kaniyo Pabidi (Budongo overlooking the Forest) Nile • Nature Walks in Murchison Falls National Park and Budongo Forest. • Nile delta Cruise • Bird Watching in Kaniyo Pabidi (Budongo Forest) Mweya Safari • 16 Classic Guest • Marasa Africa Spa • 403 km Entebbe • Kazinga Restaurant and • Queen Elizabeth National Lodge Rooms & Fitness Centre International Airport Terrace Park • 28 Deluxe Guest • Poolside deck • 2 km Mweya Airstrip • Tembo Bar • Located on the Mweya Rooms overlooking the • 57 km Kasese • Poolside deck overlooking Peninsula • 2 Wheelchair Kazinga Channel Airstrip the -

Legend " Wanseko " 159 !

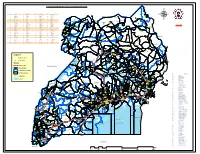

CONSTITUENT MAP FOR UGANDA_ELECTORAL AREAS 2016 CONSTITUENT MAP FOR UGANDA GAZETTED ELECTORAL AREAS FOR 2016 GENERAL ELECTIONS CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY 266 LAMWO CTY 51 TOROMA CTY 101 BULAMOGI CTY 154 ERUTR CTY NORTH 165 KOBOKO MC 52 KABERAMAIDO CTY 102 KIGULU CTY SOUTH 155 DOKOLO SOUTH CTY Pirre 1 BUSIRO CTY EST 53 SERERE CTY 103 KIGULU CTY NORTH 156 DOKOLO NORTH CTY !. Agoro 2 BUSIRO CTY NORTH 54 KASILO CTY 104 IGANGA MC 157 MOROTO CTY !. 58 3 BUSIRO CTY SOUTH 55 KACHUMBALU CTY 105 BUGWERI CTY 158 AJURI CTY SOUTH SUDAN Morungole 4 KYADDONDO CTY EST 56 BUKEDEA CTY 106 BUNYA CTY EST 159 KOLE SOUTH CTY Metuli Lotuturu !. !. Kimion 5 KYADDONDO CTY NORTH 57 DODOTH WEST CTY 107 BUNYA CTY SOUTH 160 KOLE NORTH CTY !. "57 !. 6 KIIRA MC 58 DODOTH EST CTY 108 BUNYA CTY WEST 161 OYAM CTY SOUTH Apok !. 7 EBB MC 59 TEPETH CTY 109 BUNGOKHO CTY SOUTH 162 OYAM CTY NORTH 8 MUKONO CTY SOUTH 60 MOROTO MC 110 BUNGOKHO CTY NORTH 163 KOBOKO MC 173 " 9 MUKONO CTY NORTH 61 MATHENUKO CTY 111 MBALE MC 164 VURA CTY 180 Madi Opei Loitanit Midigo Kaabong 10 NAKIFUMA CTY 62 PIAN CTY 112 KABALE MC 165 UPPER MADI CTY NIMULE Lokung Paloga !. !. µ !. "!. 11 BUIKWE CTY WEST 63 CHEKWIL CTY 113 MITYANA CTY SOUTH 166 TEREGO EST CTY Dufile "!. !. LAMWO !. KAABONG 177 YUMBE Nimule " Akilok 12 BUIKWE CTY SOUTH 64 BAMBA CTY 114 MITYANA CTY NORTH 168 ARUA MC Rumogi MOYO !. !. Oraba Ludara !. " Karenga 13 BUIKWE CTY NORTH 65 BUGHENDERA CTY 115 BUSUJJU 169 LOWER MADI CTY !. -

Uganda National Roads Network

UGANDA NATIONAL ROADS NETWORK REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN Musingo #" !P Kidepo a w K ± r i P !P e t Apoka gu a K m #" lo - g - L a o u k - #" g u P i #" n d Moyo!P g o i #"#" - t #"#" N i k #" KOBOKO M e g a #" #" #" l Nimule o #"!P a YUMBE #" u!P m ng m o #" e #" Laropi i #" ro ar KAABONG #" !P N m K #" (! - o - te o e om Kaabong#"!P g MOYO T c n o #" o #" L be Padibe !P - b K m !P LAMWO #" a oboko - Yu Yumbe #" om r K #" #" #" O #" Koboko #" #" - !P !P o Naam REGIONS AND STATIONS Moy n #" Lodonga Adjumani#" Atiak - #" Okora a #" Obongi #" !P #" #" a Loyoro #" p #" Ob #" KITGUM !P !P #" #" ong !P #" #" m A i o #" - #" - K #" Or u - o lik #" m L Omugo ul #" !P u d #" in itg o i g Kitgum t Maracha !P !P#" a K k #" !P #" #"#" a o !P p #" #" #" Atiak K #" e #" (!(! #" Kitgum Matidi l MARACHA P e - a #" A #"#" e #" #" ke d #" le G d #" #" i A l u a - Kitgum - P l n #" #" !P u ADJUMANI #" g n a Moyo e !P ei Terego b - r #" ot Kotido vu #" b A e Acholibur - K o Arua e g tr t u #" i r W #" o - O a a #" o n L m fe di - k Atanga KOTIDO eli #" ilia #" Rh #" l p N o r t h #"#" B ino Rhino !P o Ka Gulu !P ca #" #"#" aim ARUA mp - P #" #" !P Kotido Arua #" Camp Pajule go #" !P GULU on #" !P al im #" !PNariwo #" u #" - K b A ul r A r G de - i Lira a - Pa o a Bondo #" Amuru Jun w id m Moroto Aru #" ctio AMURU s ot !P #" n - A o #" !P A K i !P #" #" PADER N o r t h E a s t #" Inde w Kilak #" - #" e #" e AGAGO K #"#" !P a #" #" #" y #" a N o #" #" !P #" l w a Soroti e #"#" N Abim b - Gulu #" - K d ilak o b u !P #" Masindi !P i um !P Adilang n - n a O e #" -

Paraa Safari Lodge

Paraa Safari Lodge Established in 1954, Paraa Safari Lodge is in Murchison Falls National Park. The lodge is located in the north west of Uganda over looking one of nature's best kept secrets, the River Nile, on its journey from its source at Lake Victoria to join Lake Albert – here it is suddenly channeled into a gorge only six meters wide, and cascades 43 meters below. The earth literally trembles at Murchison Falls - one of the world's most powerful flows of natural water. The safari décor of the lodge still reflects the bygone era of early explorers, enshrined with a modern touch. The luxurious pool overlooks the winding River Nile below, which was the setting for the classic Hollywood movie "The African Queen" (starring Katharine Hepburn and Humphrey Bogart). Paraa Safari Lodge offers a unique blend of comfort, relaxation and adventure. Each of the 54 rooms is a haven of style and serenity, complete with balcony and private bathroom. In our standard single, double and twin rooms, you will find a simple safari atmosphere with a level of comfort that will not disappoint. These rooms are perfectly situated to view the lodge’s swimming pool, as well as the winding River Nile beyond. Our suites are the perfect accommodation for guests who want a little bit more space to relax. Suites have a living room with sofas where you can use the space to either relax or entertain. For those seeking the ultimate comfort; the Queen’s cottage offers a different world of experience, novelty and exclusivity. The unique architecture compliments the landscaped environment and fantastic views and the grand balcony boasts spectacular views of lush vegetation, rich wildlife, and the famous River Nile. -

“Making Bush Meat Poachers Willingly Surrender Using Integrated Poachers Awareness Programme: a Case of Murchison Falls National Park, Uganda”

“Making Bush Meat Poachers Willingly Surrender Using Integrated Poachers Awareness Programme: A Case of Murchison Falls National Park, Uganda”. S S. Kato + , J O Okumu ++ . Abstract This paper is an interesting analysis of a unique case in MFPA, one of the East African National Parks in Uganda, where wild animal poachers are targeted in an intensive integrated education and awareness programme that makes them publicly surrender with their tools. The paper brings out yet another important approach that emphasises that for sustainable management of a protected area to be attained, involvement of local community is very important as opposed to the traditional approach of law enforcement, a practice prominent in the last centaury with limited success. MFPA was one of the most tourists’ destinations in the 1960s only to be devastated during Uganda’s civil unrest of 1970s and 1980s owing to the lack of awareness by the local communities that the resources in the PA are important to them too. As the wildlife population is steadily increasing in MFPA, any approach such as the above that has demonstrated a positive move towards sustainable management is welcome. It is a strategy, which can be tried in other protected areas especially in the tropics. CONTENTS Acknowledgement………………………………………………………………….3 Summary……………………………………………………………………………4 Acronyms…………………………………………………………………………...5 1.0 Introduction ………………………………………………………………………..6 2.0 Background information …………………………………………………...............8 2.1 Location and area of Murchison Falls Protected Area……………………………8 2.2 History of establishment and management of Murchison Falls Protected Area… 9 3.0 Poaching reduction approaches ……………………………………………………11 3.1 Education and awareness programmes….…………………………………… 12 4.0 Conclusions ……………………………………………………………………… 14 Acknowledgement The coming up of this paper has been made possible by the tireless and dedicated work by the Community Conservation Department (CCD) staff of MFCA that made the initiative to try out ‘signature campaign’ strategy of community involvement. -

UCF-MFPA-Stakeholder-Forum-Report

IMPLEMENTING PARK ACTION PLANS STAKEHOLDER COORDINATION FORUM REPORT Convened by UGANDA CONSERVATION FOUNDATION November 2018 Part of the Implementing Park Action Plans project, led by IIED in partnership with Uganda Wildlife Authority, Uganda Conservation Foundation, Village Enterprise and Wildlife Conservation Society. Funded by the UK Government through the Illegal Wildlife Trade Challenge Fund. PREAMBLE The Murchison Falls Protected Area stakeholder coordination forum took place at Country Inn, Masindi on 23rd October 2018. Of 36 invited guests, speakers and organisers, 29 attended (see attendee sheet in Annex 1). Every district bordering MFPA1 was represented by at least one local government official. Uganda Wildlife Authority (UWa) was represented by staff from the Kampala headquarters, MFCA headquarters at Paraa and both Bugungu and Karuma wildlife reserves. Civil society representation included actors delivering projects in Buliisa, Masindi, Kiryandongo, Oyam and Nwoya districts. The coordination forum is funded by the UK Government through the Illegal Wildlife Trade Challenge Fund. OPENING REMARKS Adonia Bintoora, Senior Manager – Community-based Wildlife Enterprises, UWA Adonia officially opened the forum, making the following remarks. 1. As human populations worldwide increase, wildlife is becoming increasingly isolated into islands of natural habitat. Uganda is not immune to this and is facing multiple challenges in conserving wildlife whilst ensuring better futures for its people. 2. This forum came about from research conducted by IIED into the drivers of wildlife crime in Uganda and is intended for actors working around the Murchison Falls Protected Area. UWA staff in MFCA are just 368 people – those 368 people cannot be expected to protect wildlife in isolation from the thousands of people who live around the park, or without the support from other stakeholders operating in these areas. -

Paraa Safari Lodge Magniicent View of Murchison Falls

Paraa Safari Lodge Magniicent view of Murchison falls Established in 1954, Paraa Safari Lodge is located in Murchison Falls National Park. The The safari décor of the lodge still relects the bygone era of early explorers, enshrined with lodge is located in the northwest corner of Uganda, overlooking one of nature’s best- a modern touch. The luxurious pool overlooks the winding River Nile below, which was kept secrets, the River Nile. On the journey from its source at Lake Victoria to join Lake the setting for the classic Hollywood movie “The African Queen”. Albert, the River Nile is suddenly channelled into a gorge only 6 meters / 20 feet wide, and cascades 43 meters / 141 feet below. The earth literally trembles at Murchison Falls - one Enjoy a variety of excursions and activities; from exhilarating safari drives to river safaris, of the world’s most powerful lows of natural water. ending at the foot of Murchison Falls or the Nile Delta, where the Victoria Nile empties into Lake Albert and the Blue Nile begins. For the more adventurous, one can trek up to Paraa Safari Lodge ofers a unique blend of comfort, relaxation and adventure. Each of the top of the falls and marvel at the views through the mist. A variety of ecosystems and the rooms is a haven of style and serenity, complete with balcony and private bathroom. an impressive 451 species of birds await you at Paraa. Murchison Falls was the setting and background for Humphrey Bogart in John Huston’s well known movie in 1951, The African Queen, ilmed on the location along the Murchison Nile as well as on Lake Albert. -

Uganda & Rwanda

15 Days Itinerary Uganda & Rwanda Day 1 International Flights to Entebbe, Uganda Day 2 VIP Assistance - Entebbe Airport · VIP Assistance through Customs & Immigration. Welcome to Uganda! On arrival in Entebbe you will be met off the airplane by our VIP MEET & GREET staff (look for your name on a sign). They will then assist you to the front of the line to clear Uganda's immigration & customs formalities. Transfer · Entebbe Airport to Hotel No. 5 Entebbe Notes You will then be helped to collect your luggage and proceed to the Arrivals Hall where you will be met by your driver (look for your name on a sign). You will then be transferred to Hotel No. 5 Entebbe. 1 Hotel No. 5 Entebbe +256 797 282 908 +256 797 282 908 5 Edna Road Entebbe, Uganda 5 Edna Road Entebbe, Uganda 2 Nights Day 3 Uganda - Ngamba Chimpanzee Sanctuary Your guide will meet you at the lobby for a 15 minute drive to the pier, arriving in time for a safety briefing and a boat ride to the famous Ngamba Chimpanzee Sanctuary. You will later get back on the boat in time for your 45-50 minutes ride back to Entebbe mainland arriving at 12:45pm. Entebbe Cultural City Tour Lunch at a local restaurant. (costs to be settled direct by you) Take a relaxed ride down to the lake and visit the landing site, local market and get an insight of the local fisher man’s daily lifestyle. Walk i for local purchases and bargain like a Ugandan. Fishing is the major economic activity here and the setup of shops, restaurants, sailing boats is quite unique. -

Vote: 606 2014/15 Quarter 4

Local Government Quarterly Performance Report Vote: 606 Nwoya District 2014/15 Quarter 4 Structure of Quarterly Performance Report Summary Quarterly Department Workplan Performance Cumulative Department Workplan Performance Location of Transfers to Lower Local Services and Capital Investments Submission checklist I hereby submit _________________________________________________________________________. This is in accordance with Paragraph 8 of the letter appointing me as an Accounting Officer for Vote:606 Nwoya District for FY 2014/15. I confirm that the information provided in this report represents the actual performance achieved by the Local Government for the period under review. Name and Signature: Chief Administrative Officer, Nwoya District Date: 8/5/2015 cc. The LCV Chairperson (District)/ The Mayor (Municipality) Page 1 Local Government Quarterly Performance Report Vote: 606 Nwoya District 2014/15 Quarter 4 Summary: Overview of Revenues and Expenditures Overall Revenue Performance Cumulative Receipts Performance Approved Budget Cumulative % Receipts Budget UShs 000's Received 1. Locally Raised Revenues 663,294 558,939 84% 2a. Discretionary Government Transfers 1,681,095 1,412,132 84% 2b. Conditional Government Transfers 8,607,330 6,938,778 81% 2c. Other Government Transfers 2,793,907 3,095,180 111% 3. Local Development Grant 289,343 289,344 100% 4. Donor Funding 5,624,868 1,368,196 24% Total Revenues 19,659,837 13,662,568 69% Overall Expenditure Performance Cumulative Releases and Expenditure Perfromance Approved Budget Cumulative -

Regional Development for Amuru and Nwoya Districts

PART 1: RURAL ROAD MASTER PLANNIN G IN AMURU AND NWOYA DISTRICTS SECTION 2: REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT FOR AMURU AND NWOYA DISTRICTS Project for Rural Road Network Planning in Northern Uganda Final Report Vol.2: Main Report 3. PRESENT SITUATION OF AMURU AND NWOYA DISTRICTS 3.1 Natural Conditions (1) Location Amuru and Nwoya Districts are located in northern Uganda. These districts are bordered by Sudan in the north and eight Ugandan Districts on the other sides (Gulu, Lamwo, Adjumani, Arua, Nebbi, Bulisa, Masindi and Oyam). (2) Land Area The total land area of Amuru and Nwoya Districts is about 9,022 sq. km which is 3.7 % of that of Uganda. It is relatively difficult for the local government to administer this vast area of the district. (3) Rivers The Albert Nile flows along the western border of these districts and the Victoria Nile flows along their southern borders as shown in Figure 3.1.2. Within Amuru and Nwoya Districts, there are six major rivers, namely the Unyama River, the Ayugi River, the Omee River, the Aswa River, Tangi River and the Ayago River. These rivers are major obstacles to movement of people and goods, especially during the rainy season. (4) Altitude The altitude ranges between 600 and 1,200 m above sea level. The altitude of the south- western area that is a part of Western Rift Valley is relatively low and ranges between 600 and 800 m above sea level. Many wild animals live near the Albert Nile in the western part of Amuru and Nwoya Districts and near the Victoria Nile in the southern part of Nwoya District because of a favourable climate.