Appalachia Alpina

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

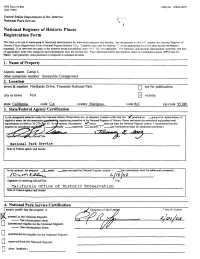

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMBNo. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior » , • National Park Service V National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determination for individual properties and districts Sec instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" lor 'not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and area of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10- 900A). Use typewriter, word processor or computer to complete all items. 1. Name of Property____________________________________________________ historic name Camp 4 other name/site number Sunnyside Campground__________________________________________ 2. Location_______________________________________________________ street & number Northside Drive, Yosemite National Park |~1 not for publication city or town N/A [_xj vicinity state California code CA county Mariposa code 043 zip code 95389 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this Itjiomination _irquest for determination of eligibility meets the documentationsJand»ds-iJar -

Alps & Dolomites 2016

Area Notes Untitled (Gordale Scar?) Joseph Farington (1747-1821) Undated. Pen and ink and watercolor over graphite on wove paper. 18 x 127/8 inches. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection. 259 LINDSAY GRIFFIN Alps & Dolomites 2016 Stephan Siegrist on the third pitch above the central ledge of Metanoia, on the Eiger. (Archive Metanoia) 261 262 T HE A LPINE J OURN A L 2 0 1 7 A LP S & D OLOMI T E S 2 0 1 6 263 Thomas Huber on one of the harder rock pitches of Metanoia. Note the hot air The line of Amore di Vetro on the north-east face of the Piz Badile. (Marcel balloon up and left. (Archive Metanoia) Schenk) he highlights of 2016, the really major ascents during both summer and one 8mm bolt on a belay, as a fall at this point would have ripped the whole Twinter, largely took place on the some of the most celebrated peaks party off the mountain. The climbers confirmed that the 1,800m route (VII, of the Alpine chain: Eiger, Grandes Jorasses, Piz Badile, Civetta, Cima A4, M6) set new standards of alpinism at the time. Or as Huber said: ‘what Grande. In particular, rare winter conditions in the Bregaglia-Masino led he [Lowe] accomplished is really just madness.’ The climb, and Lowe’s to some truly remarkable ascents. ground-breaking career, is celebrated in the award-winning film Metanoia. There were several outstanding ascents on the north face of the Eiger, but On the left side of the wall Tom Ballard and Marcin Tomaszewski spent none that matches the second ascent of the legendary Metanoia by Thomas seven days, finishing on 6 December, climbing a new route on the north Huber, Roger Schaeli and Stephan Siegrist. -

A Statistical Analysis of Mountaineering in the Nepal Himalaya

The Himalaya by the Numbers A Statistical Analysis of Mountaineering in the Nepal Himalaya Richard Salisbury Elizabeth Hawley September 2007 Cover Photo: Annapurna South Face at sunrise (Richard Salisbury) © Copyright 2007 by Richard Salisbury and Elizabeth Hawley No portion of this book may be reproduced and/or redistributed without the written permission of the authors. 2 Contents Introduction . .5 Analysis of Climbing Activity . 9 Yearly Activity . 9 Regional Activity . .18 Seasonal Activity . .25 Activity by Age and Gender . 33 Activity by Citizenship . 33 Team Composition . 34 Expedition Results . 36 Ascent Analysis . 41 Ascents by Altitude Range . .41 Popular Peaks by Altitude Range . .43 Ascents by Climbing Season . .46 Ascents by Expedition Years . .50 Ascents by Age Groups . 55 Ascents by Citizenship . 60 Ascents by Gender . 62 Ascents by Team Composition . 66 Average Expedition Duration and Days to Summit . .70 Oxygen and the 8000ers . .76 Death Analysis . 81 Deaths by Peak Altitude Ranges . 81 Deaths on Popular Peaks . 84 Deadliest Peaks for Members . 86 Deadliest Peaks for Hired Personnel . 89 Deaths by Geographical Regions . .92 Deaths by Climbing Season . 93 Altitudes of Death . 96 Causes of Death . 97 Avalanche Deaths . 102 Deaths by Falling . 110 Deaths by Physiological Causes . .116 Deaths by Age Groups . 118 Deaths by Expedition Years . .120 Deaths by Citizenship . 121 Deaths by Gender . 123 Deaths by Team Composition . .125 Major Accidents . .129 Appendix A: Peak Summary . .135 Appendix B: Supplemental Charts and Tables . .147 3 4 Introduction The Himalayan Database, published by the American Alpine Club in 2004, is a compilation of records for all expeditions that have climbed in the Nepal Himalaya. -

Wall Free Climb in the World by Tommy Caldwell

FREE PASSAGE Finding the path of least resistance means climbing the hardest big- wall free climb in the world By Tommy Caldwell Obsession is like an illness. At first you don't realize anything is happening. But then the pain grows in your gut, like something is shredding your insides. Suddenly, the only thing that matters is beating it. You’ll do whatever it takes; spend all of your time, money and energy trying to overcome. Over months, even years, the obsession eats away at you. Then one day you look in the mirror, see the sunken cheeks and protruding ribs, and realize the toll taken. My obsession is a 3,000-foot chunk of granite, El Capitan in Yosemite Valley. As a teenager, I was first lured to El Cap because I could drive my van right up to the base of North America’s grandest wall and start climbing. I grew up a clumsy kid with bad hand-eye coordination, yet here on El Cap I felt as though I had stumbled into a world where I thrived. Being up on those steep walls demanded the right amount of climbing skill, pain tolerance and sheer bull-headedness that came naturally to me. For the last decade El Cap has beaten the crap out of me, yet I return to scour its monstrous walls to find the tiniest holds that will just barely go free. So far I have dedicated a third of my life to free climbing these soaring cracks and razor-sharp crimpers. Getting to the top is no longer important. -

El Capitan, the Direct Line California, Yosemite National Park the Direct Line (39 Pitches, 5.13+), A.K.A

AAC Publications El Capitan, The Direct Line California, Yosemite National Park The Direct Line (39 pitches, 5.13+), a.k.a. the Platinum Wall, is a brand-new, mostly independent free line on El Capitan. It begins just left of the Nose and continues up the steepening blankness, following a circuitous path of 22 technical slab pitches before accessing the upper half of the Muir, either by the PreMuir (recommended) or the Shaft. From where these two routes meet, it continues up the aesthetic upper Muir corner system to access wild and overhanging terrain on the right wall. Bolted pitches take you to the prow between the Muir and Nose, and the route finishes close to the original Muir. In 2006, envisioning a possible variation to the Nose, Justen Sjong and I had explored multiple possibilities for exiting the Half Dollar on the Salathé Wall route and finding some way to access Triple Direct Ledge, 80’ below Camp IV on the Nose. Beginning in 2010, I picked up where we left off and began searching for the definitive free climbing path. During that hot and dry summer in 2010, it becameclear there was a much more direct and independent way to climb the slabs to Triple Direct Ledge than using the Freeblast start to the Salathé. With that exciting realization, I just couldn’t see finishing on the Nose, but instead envisioned a nearly independent route all the way up the wall. I took it on faith that there had to be a way to exit the Muir corner. Each tantalizing prospect on the upper wall would either yield a new approach or would clarify a dead end (which is also helpful). -

Tibet's Biodiversity

Published in (Pages 40-46): Tibet’s Biodiversity: Conservation and Management. Proceedings of a Conference, August 30-September 4, 1998. Edited by Wu Ning, D. Miller, Lhu Zhu and J. Springer. Tibet Forestry Department and World Wide Fund for Nature. China Forestry Publishing House. 188 pages. People-Wildlife Conflict Management in the Qomolangma Nature Preserve, Tibet. By Rodney Jackson, Senior Associate for Ecology and Biodiversity Conservation, The Mountain Institute, Franklin, West Virginia And Conservation Director, International Snow Leopard Trust, Seattle, Washington Presented at: Tibet’s Biodiversity: Conservation and Management. An International Workshop, Lhasa, August 30 - September 4, 1998. 1. INTRODUCTION Established in March 1989, the Qomolangma Nature Preserve (QNP) occupies 33,819 square kilometers around the world’s highest peak, Mt. Everest known locally as Chomolangma. QNP is located at the junction of the Palaearctic and IndoMalayan biogeographic realms, dominated by Tibetan Plateau and Himalayan Highland ecoregions. Species diversity is greatly enhanced by the extreme elevational range and topographic variation related to four major river valleys which cut through the Himalaya south into Nepal. Climatic conditions differ greatly from south to north as well as in an east to west direction, due to the combined effect of exposure to the monsoon and mountain-induced rain s- hadowing. Thus, southerly slopes are moist and warm while northerly slopes are cold and arid. Li Bosheng (1994) reported on biological zonation and species richness within the QNP. Surveys since the 1970's highlight its role as China’s only in-situ repository of central Himalayan ecosystems and species with Indian subcontinent affinities. Most significant are the temperate coniferous and mixed broad-leaved forests with their associated fauna that occupy the deep gorges of the Pungchu, Rongshar, Nyalam (Bhote Kosi) and Kyirong (Jilong) rivers. -

Washington State University Alumni Achievement Award Recipients

Washington State University ALPHA Alumni Achievement Award Recipients David Abbott - 1950 Awarded 1982 For loyalty and dedication to his alma mater as a tireless worker for the athletic program and the Alumni Association, personifying the intent of this award. John Abelson - 1960 Awarded 1993 For outstanding contributions to the understanding of protein biosynthesis and national recognition to the understanding of protein biosynthesis and national recognition in the fields of molecular biology and biochemistry. Yasuharu Agarie - 1972 Awarded 1984 For outstanding contributions to the field of educational measurement, bringing him international recognition, culminating in the presidency of the University of Ryukyu. Manzoor Ahmad - 1961 & 1966 Awarded 2005 For distinguished leadership and accomplishments in teaching, research and administration in Veterinary Medicine and Animal Reproduction, significantly improving the quality of Animal Sciences in Pakistan, bringing pride and distinction to his alma mater. Robert Alessandro - 1957 Awarded 2005 For a lifetime of extraordinary leadership and service to his profession and community. He exemplifies Cougar Spirit with his boundless enthusiasm for and loyal support of Washington State University. He brings pride to his alma mater. Sherman J. Alexie, Jr. - 1991 Awarded 1994 For recognition as an internationally acclaimed author and Native American lecturer, including the publication of five books of fiction and poetry. Louis Allen - 1940 Awarded 1991 For international recognition and distinction as an expert in the field management, bringing credit to his Alma Mater. Louis Allen - 1941 Awarded 1999 Through Lou and Ruth Allen's leadership, a vision has been born; their legacy is WSU's continued accomplishments on behalf of those it serves. -

Stevie Haston Aleš Česen Malcolm Bass Tom Ballard Steve Skelton F.Lli Franchini Korra Pesce

# 33 Stile Alpino Luoghi & Montagne MONTE BIANCO BHAGIRATHI III CIVETTA KISHTWAR SHIVLING GASHERBRUM IV HIMALAYA MALTA TAULLIRAJU Protagonisti STEVIE HASTON ALEš ČESEN MALCOLM BASS TOM BALLARD STEVE SKELTON F.LLI FRANCHINI KORRA PESCE Speciale PILASTRO ROSSO DEL BROUILLARD In collaborazione con: ALPINE STUDIO EDITORE Trimestrale anno VIII n° 33 settembre 2016 (n. 3/2016) € 4,90 La giacca più leggera e impermeabile del momento LIGHTWEIGHT WITHOUT COMPROMISE MINIMUS 777 JACKET Con un peso di soli 139g, la Minimus 777 è una giacca per Alpinismo e da Trail di una leggerezza estrema, con 3 strati impermeabili, una traspirabilità elevata e una comprimibilità senza precedenti. Pertex® Shield + exclusive technology: 7 denier face, 7 micron membrane, 7 denier tricot backer montane.eu La giacca più leggera e EDITORIAL # 33 impermeabile del momento • Firstly I would like to openly admit that I do not really like to write about or com- ment on other peoples mountaineering endeavors, because it is impossible to comple- tely understand an experience in the mountains unless you have lived it yourself. Ten years after my predecessor I will have the difficult task to replace Fabio Palma in writing the editorials of Stile Alpino. Certainly he is better skilled than me in writing and has been one of the creators of this magazine founded by the Ragni di Lecco group. Nonetheless, I will try to be up to the job helping to select the last ascents around the world and to suggest new places but always taking care to include ascents in the Alps and close to home. The objective of Stile Alpino is to improve and steadily grow in order to publish ar- ticles, that might not have been published before, on ascents in unknown or known areas. -

WINTER 2003-04 VOLUME 3, NUMBER 1 Washington Tate Magazine

WINTER 2003-04 VOLUME 3, NUMBER 1 Washington tate magazine features Washington’s Marine Highway 18 by Pat Caraher • photos by Laurence Chen Washington state ferries appear in a million CONTENTS tourists’ photos. But they are also a vital link in the state’s transportation system. Mike Thorne ’62 aims to keep them that way—in spite of budgetary woes. On Call 23 by Pat Caraher • photos by Shelly Hanks Student firefighters at Washington State University have a long tradition of protecting their campus. Boeing’s Mike Bair & the 7E7 26 by Bryan Corliss Wherever Boeing ends up building it, the 7E7 will be lighter, more fuel efficient, and more comfortable. It’s up to Mike Bair ’78 to get this new airplane off the ground. A Bug-Eat-Bug World 30 by Mary Aegerter • photos by Robert Hubner If you can put other insects to work eating the insects that are bothering you, everybody wins. Except the pests. NO GREEN CARDS REQUIRED STAN HOYT LED THE WAY TO 18 FRIENDLIER MANAGEMENT LAURENCE CHEN Putting on the Ritz 36 by Andrea Vogt • illustrations by David Wheeler The child of Swiss peasants, no one would have expected César Ritz to become the hotelier of kings. But then, who would have expected WSU to add American business management methods to the fine art of European hotellerie in the town where Ritz got his start? 23 Cover: Washington State Ferry. See story, page 18. Photograph by Laurence Chen. 30 Washington tate CONNECTING WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY, THE STATE, AND THE WORLD magazine panoramas Letters 2 The Lure 4 Drug IDs 6 PERSPECTIVE: Blackouts -

Pakistan 1995

LINDSAY GRIFFIN & DAVID HAMILTON Pakistan 1995 Thanks are due to Xavier Eguskitza, Tafeh Mohammad andAsem Mustafa Awan for their help in providing information. ast summer in the Karakoram was one of generally unsettled weather L conditions. Intermittent bad weather was experienced from early June and a marked deterioration occurred from mid-August. The remnants of heavy snow cover from a late spring fall hampered early expeditions, while those arriving later experienced almost continuous precipitation. In spite of these difficulties there was an unusually high success rate on both the 8000m and lesser peaks. Pakistan Government statistics show that 59 expe ditions from 16 countries received permits to attempt peaks above 6000m. Of the 29 expeditions to 8000m peaks 17 were successful. On the lower peaks II of the 29 expeditions succeeded. There were 14 fatalities (9 on 8000m peaks) among the 384 foreign climbers; a Pakistani cook and porter also died in separate incidents. The action of the Pakistan Government in limiting the number of per mits issued for each of the 8000m peaks to six per season has led to the practice of several unconnected expeditions 'sharing' a permit, an un fortunate development which may lead to complicated disputes with the Pakistani authorities in the future. Despite the growing commercialisation of high-altitude climbing, there were only four overtly commercial teams on the 8000m peaks (three on Broad Peak and one on Gasherbrum II). However, it is clear that many places on 'non-commercial' expeditions were filled by experienced climbers able to supply substantial funds from their own, or sponsors', resources. -

Route Was Then Soloed on the Right Side Ofthe W Face Ofbatian (V + ,A·L) by Drlik, Which Is Now Established As the Classic Hard Line on the Mountain

route was then soloed on the right side ofthe W face ofBatian (V + ,A·l) by Drlik, which is now established as the classic hard line on the mountain. On the Buttress Original Route, Americans GeoffTobin and Bob Shapiro made a completely free ascent, eliminating the tension traverse; they assessed the climb as 5.10 + . Elsewhere, at Embaribal attention has concentrated on the Rift Valley crag-further details are given in Mountain 73 17. Montagnes 21 82 has an article by Christian Recking on the Hoggar which gives brief descriptions of 7 of the massifs and other more general information on access ete. The following guide book is noted: Atlas Mountains Morocco R. G. Collomb (West Col Productions, 1980, pp13l, photos and maps, £6.00) ASIA PAMIRS Russian, Polish, Yugoslav and Czechoslovak parties were responsible for a variety ofnew routes in 1979. A Polish expedition led by Janusz Maczka established a new extremely hard route on the E face of Liap Nazar (5974m), up a prominent rock pillar dubbed 'one of the mOSt serious rock problems of the Pamir'. It involved 70 pitches, 40 ofthem V and VI, all free climbed in 5 days, the summit being reached on 6 August. The party's activities were halted at one point by stone avalanches. On the 3000m SW face ofPeak Revolution (6974m) 2 teams, one Russian and one Czech/Russian, climbed different routes in July 1979. KARAKORAM Beginning in late March 1980, Galen Rowell, leader, Dan Asay, Ned Gillette and Kim Schmitz made a 435km ski traverse of the Karakoram in 42 days, setting off carrying 50kg packs. -

Alps & Dolomites 2015

Area Notes John Harlin Rob Fairley, 1969. (Acrylic on board. 150cm x 120cm. Destroyed.) 269 LINDSAY GRIFFIN Alps & Dolomites 2015 or a variety of reasons – weather, politics and, in the case of Nepal, Fearthquakes – significantly fewer major new lines than normal were completed in the world’s mountains during 2015. This was also true in the Alps, where dry conditions and, during the summer, incredibly warm tem- peratures, confined most to objectively safe rock. Although there were a number of new additions to the Mont Blanc range, there appear to have been no leading first ascents. On 18 August 1983, three of the top alpinists of that time, Eric Bellin, Jean-Marc Boivin and Martial Moioli started up the compact granite face to the right of the initial corner system of the American Route on the south face of the Fou, emerging at the summit the following night under a full moon. Their route, Balade au Clair de Lune, is mixed free and aid, and has seen few repeats. There are several fine but often poorly protected pitches of free climbing up to 6c, and at least one demanding aid pitch of A3/A4 (hooks and copperheads) above the point where the line crosses the famous Diagonal Crack. Ascents of the south face have declined in recent years due to the danger of access during the summer months. Climbers now either choose spring to approach on ski or the more lengthy option of traversing the main ridge of the Aiguilles from the Aiguille du Midi and abseiling to the base of the route.