Python Brongersmai (Stull, 1938) Python Brongersmai Se Aprovecha

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Final Rule to List Reticulated Python And

Vol. 80 Tuesday, No. 46 March 10, 2015 Part II Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife 50 CFR Part 16 Injurious Wildlife Species; Listing Three Anaconda Species and One Python Species as Injurious Reptiles; Final Rule VerDate Sep<11>2014 18:14 Mar 09, 2015 Jkt 235001 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4717 Sfmt 4717 E:\FR\FM\10MRR2.SGM 10MRR2 mstockstill on DSK4VPTVN1PROD with RULES2 12702 Federal Register / Vol. 80, No. 46 / Tuesday, March 10, 2015 / Rules and Regulations DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Services Office, U.S. Fish and Wildlife 3330) to list Burmese (and Indian) Service, 1339 20th Street, Vero Beach, pythons, Northern African pythons, Fish and Wildlife Service FL 32960–3559; telephone 772–562– Southern African pythons, and yellow 3909 ext. 256; facsimile 772–562–4288. anacondas as injurious wildlife under 50 CFR Part 16 FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Bob the Lacey Act. The remaining five RIN 1018–AV68 Progulske, Everglades Program species (reticulated python, boa Supervisor, South Florida Ecological constrictor, green anaconda, [Docket No. FWS–R9–FHC–2008–0015; Services Office, U.S. Fish and Wildlife DeSchauensee’s anaconda, and Beni FXFR13360900000–145–FF09F14000] Service, 1339 20th Street, Vero Beach, anaconda) were not listed at that time and remained under consideration for Injurious Wildlife Species; Listing FL 32960–3559; telephone 772–469– 4299. If you use a telecommunications listing. With this final rule, we are Three Anaconda Species and One listing four of those species (reticulated Python Species as Injurious Reptiles device for the deaf (TDD), please call the Federal Information Relay Service python, green anaconda, AGENCY: Fish and Wildlife Service, (FIRS) at 800–877–8339. -

Investigations Into the Presence of Nidoviruses in Pythons Silvia Blahak1, Maria Jenckel2,3, Dirk Höper2, Martin Beer2, Bernd Hoffmann2 and Kore Schlottau2*

Blahak et al. Virology Journal (2020) 17:6 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-020-1279-5 RESEARCH Open Access Investigations into the presence of nidoviruses in pythons Silvia Blahak1, Maria Jenckel2,3, Dirk Höper2, Martin Beer2, Bernd Hoffmann2 and Kore Schlottau2* Abstract Background: Pneumonia and stomatitis represent severe and often fatal diseases in different captive snakes. Apart from bacterial infections, paramyxo-, adeno-, reo- and arenaviruses cause these diseases. In 2014, new viruses emerged as the cause of pneumonia in pythons. In a few publications, nidoviruses have been reported in association with pneumonia in ball pythons and a tiger python. The viruses were found using new sequencing methods from the organ tissue of dead animals. Methods: Severe pneumonia and stomatitis resulted in a high mortality rate in a captive breeding collection of green tree pythons. Unbiased deep sequencing lead to the detection of nidoviral sequences. A developed RT-qPCR was used to confirm the metagenome results and to determine the importance of this virus. A total of 1554 different boid snakes, including animals suffering from respiratory diseases as well as healthy controls, were screened for nidoviruses. Furthermore, in addition to two full-length sequences, partial sequences were generated from different snake species. Results: The assembled full-length snake nidovirus genomes share only an overall genome sequence identity of less than 66.9% to other published snake nidoviruses and new partial sequences vary between 99.89 and 79.4%. Highest viral loads were detected in lung samples. The snake nidovirus was not only present in diseased animals, but also in snakes showing no typical clinical signs. -

P. 1 AC27 Inf. 7 (English Only / Únicamente En Inglés / Seulement

AC27 Inf. 7 (English only / únicamente en inglés / seulement en anglais) CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA ____________ Twenty-seventh meeting of the Animals Committee Veracruz (Mexico), 28 April – 3 May 2014 Species trade and conservation IUCN RED LIST ASSESSMENTS OF ASIAN SNAKE SPECIES [DECISION 16.104] 1. The attached information document has been submitted by IUCN (International Union for Conservation of * Nature) . It related to agenda item 19. * The geographical designations employed in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CITES Secretariat or the United Nations Environment Programme concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The responsibility for the contents of the document rests exclusively with its author. AC27 Inf. 7 – p. 1 Global Species Programme Tel. +44 (0) 1223 277 966 219c Huntingdon Road Fax +44 (0) 1223 277 845 Cambridge CB3 ODL www.iucn.org United Kingdom IUCN Red List assessments of Asian snake species [Decision 16.104] 1. Introduction 2 2. Summary of published IUCN Red List assessments 3 a. Threats 3 b. Use and Trade 5 c. Overlap between international trade and intentional use being a threat 7 3. Further details on species for which international trade is a potential concern 8 a. Species accounts of threatened and Near Threatened species 8 i. Euprepiophis perlacea – Sichuan Rat Snake 9 ii. Orthriophis moellendorfi – Moellendorff's Trinket Snake 9 iii. Bungarus slowinskii – Red River Krait 10 iv. Laticauda semifasciata – Chinese Sea Snake 10 v. -

AC27 Inf. 17 (Rev.1) (English Only / Únicamente En Inglés / Seulement En Anglais)

AC27 Inf. 17 (Rev.1) (English only / únicamente en inglés / seulement en anglais) CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA ____________ Twenty-seventh meeting of the Animals Committee Veracruz (Mexico), 28 April – 3 May 2014 INSPECTION MANUAL FOR USE IN COMMERCIAL REPTILE BREEDING FACILITIES IN SOUTHEAST ASIA 1. The attached information document has been submitted by the Secretariat and has been prepared by TRAFFIC* in relation to agenda item 9. * The geographical designations employed in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CITES Secretariat or the United Nations Environment Programme concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The responsibility for the contents of the document rests exclusively with its author. AC27 Doc. 17 (Rev.1) – p. 1 Inspection Manual for use in Commercial Reptile Breeding Facilities in Southeast Asia EU- CITES Capacity - building project N o . S - 408 2013 CITES Secretariat About the EU-CITES Capacity-building project The project Strengthening CITES implementation capacity of developing countries to ensure sustainable wildlife management and non-detrimental trade was approved for funding by the European Union in 2009. A major challenge for many countries is the difficulty in meeting the requirements for trade in CITES-listed species, ranging from legal sourcing and sustainability requirements, to the effective control of legal trade and deterrence of illegal trade. Mechanisms exist in CITES and in both exporting and importing countries that promote and facilitate compliance – although Parties are often hampered by a lack of capacity or a lack of current biological or trade information with respect to certain species. -

The Discovery of XY Sex Chromosomes in a Boa and Python

Current Biology, Volume 27 Supplemental Information The Discovery of XY Sex Chromosomes in a Boa and Python Tony Gamble, Todd A. Castoe, Stuart V. Nielsen, Jaison L. Banks, Daren C. Card, Drew R. Schield, Gordon W. Schuett, and Warren Booth Figure S1. PCR validation of male-specific RAD markers in boa and python. Related to Figure 1. A. Male-biased amplification of RAD marker TCBoa_2918 in eleven male and eleven female Boa imperator. Individual specimen ID numbers are listed below the gel image. B. Male-biased amplification of RAD marker TCBoa_2918 in an additional eight male and eleven female Boa imperator. Individual specimen ID numbers are listed below the gel image. C. Photograph of South American Boa (Boa constrictor) from Goiás, Brazil. D. Male-biased amplification of RAD marker TCBoa_2918 in three male and three female Boa constrictor. Individual specimen ID numbers are listed below the gel image. E. Male-biased amplification of RAD marker M3 in twelve male and twelve female Python bivittatus. Individual specimen ID numbers are listed below the gel image in panel F. F. Male-specific restriction digest of PCR amplicon (PCR-RFLP) from RAD marker M10 in twelve male and twelve female Python bivittatus. Individual specimen ID numbers are listed below the gel image. G. Cartoon illustrating PCR amplicons from the python RAD marker M10. The X and Y alleles are illustrated including the approximate position of the Y chromosome-specific SpeI restriction site. H. Gel image of python RAD marker M10 showing difference between digested and undigested PCR amplicons from a male Python bivittatus. -

G Iant Snakes

Copyrighted Material Some pages are omitted from this book preview. Giant Snakes Giant Giant Snakes A Natural History John C. Murphy & Tom Crutchfield Snakes, particularly venomous snakes and exceptionally large constricting snakes, have haunted the human brain for a millennium. They appear to be responsible for our excellent vision, as well as the John C. Murphy & Tom Crutchfield & Tom C. Murphy John anxiety we feel. Despite the dangers we faced in prehistory, snakes now hold clues to solving some of humankind’s most debilitating diseases. Pythons and boas are capable of eating prey that is equal to more than their body weight, and their adaptations for this are providing insight into diabetes. Fascination with snakes has also drawn many to keep them as pets, including the largest species. Their popularity in the pet trade has led to these large constrictors inhabiting southern Florida. This book explores what we know about the largest snakes, how they are kept in captivity, and how they have managed to traverse ocean barriers with our help. Copyrighted Material Some pages are omitted from this book preview. Copyrighted Material Some pages are omitted from this book preview. Giant Snakes A Natural History John C. Murphy & Tom Crutchfield Copyrighted Material Some pages are omitted from this book preview. Giant Snakes Copyright © 2019 by John C. Murphy & Tom Cructhfield All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America First Printing March 2019 ISBN 978-1-64516-232-2 Paperback ISBN 978-1-64516-233-9 Hardcover Published by: Book Services www.BookServices.us ii Copyrighted Material Some pages are omitted from this book preview. -

Meeting Handout

CONGRESSIONAL BUDGET OFFICE COST ESTIMATE October 9, 2009 H.R.2811 A bill to amend title 18, United States Code, to include constrictor snakes of the species Python genera as an inj urious animal As ordered reported by the House Committee on the Judicimy on July 29, 2009 CBO estimates that implementing H.R. 2811 would have no significant cost to the federal government. Enacting the bill could affect direct spending and revenues, but CBO estimates that any such effects would not be significant. H.R. 2811 would make it a federal crime to impOli or ship certain snakes into the United States. Because the bill would establish a new offense, the government would be able to pursue cases that it otherwise would not be able to prosecute. We expect that H.R. 2811 would apply to a relatively small number of offenders, so any increase in costs for law enforcement, court proceedings, or prison operations would not be significant. Any such costs would be subject to the availability of appropriated funds. Because those prosecuted and convicted under H.R. 2811 could be subject to criminal [mes, the federal government might collect additional fines if the legislation is enacted. Criminal fines are recorded as revenues, deposited in the Crime Victims Fund, and later spent. CBO expects that any additional revenues and direct spending would not be significant because of the small number of cases likely to be affected. Under H.R. 2811, entities such as zoos would need permits to import or transport the affected species of snakes. Based on information provided by the U.S. -

Harvest Monitoring of Snakes in Trade a Guide for Wildlife Managers

Harvest monitoring of snakes in trade A guide for wildlife managers D.J.D. Natusch, L. Fitzgerald, J.A. Lyons, A.S.C. Toudonou, P. Micucci and T. Waller OCCASIONAL PAPER OF THE IUCN SPECIES SURVIVAL COMMISSION NO. 65 Southeast Asian Reptile Conservation Alliance About IUCN IUCN is a membership Union uniquely com- posed of both government and civil socie- ty organisations. It provides public, private and non-governmental organisations with the knowledge and tools that enable human progress, economic development and nature conservation to take place together. Created in 1948, IUCN is now the world’s larg- est and most diverse environmental network, harnessing the knowledge, resources and reach of more than 1,300 Member organisa- tions and some 13,000 experts. It is a leading provider of conservation data, assessments and analysis. Its broad membership enables IUCN to fill the role of incubator and trusted repository of best practices, tools and inter- national standards. IUCN provides a neutral space in which di- verse stakeholders including governments, NGOs, scientists, businesses, local commu- nities, indigenous peoples organisations and others can work together to forge and imple- ment solutions to environmental challenges and achieve sustainable development. Working with many partners and supporters, IUCN implements a large and diverse portfo- lio of conservation projects worldwide. Com- bining the latest science with the traditional knowledge of local communities, these pro- jects work to reverse habitat loss, restore eco- systems and improve people’s well-being. www.iucn.org https://twitter.com/IUCN/ Harvest monitoring of snakes in trade A guide for wildlife managers Harvest monitoring of snakes in trade A guide for wildlife managers D.J.D. -

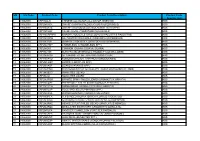

Product-Code-For-Cites-(Animal).Pdf

S/N HS Code Product Code Product Code Description Product Code Quantity Unit 1 01062000 CRP1NALSI CHINESE ALLIGATOR (ALLIGATOR SINENSIS) HDS 2 01062000 CRP2NPAPA DWARF CAIMAN (PALEOSUCHUS PALPEBROSUS) HDS 3 01062000 CRP1NOSTE DWARF CROCODILE (OSTEOLAEMUS TETRASPIS) HDS 4 01062000 CRP1NTOSC FALSE GAVIAL (TOMISTOMA SCHLEGELII) HDS 5 01062000 CRP1NCRPAPA MARSH CROCODILE (CROCODYLUS PALUSTRIS PALUSTRIS) HDS 6 01062000 CRP1NCRPO SALTWATER CROCODILE (CROCODYLUS POROSUS) HDS 7 01062000 CRP1NCRSI SIAMESE CROCODILE (CROCODYLUS SIAMENSIS) HDS 8 01062000 CRP2NCHSP CHAMELEON (CHAMAELEON SPP.) HDS 9 01062000 CRP2NIGIG COMMON IGUANA (IGUANA IGUANA) HDS 10 01062000 CRP1NLYWI ELECTRIC BLUE GECKO (LYGODACTYLUS WILLIAMSI) HDS 11 01062000 CRP2NHESU GILA MONSTER (HELODERMA SUSPECTUM) HDS 12 01062000 CRP1NVAKO KOMODO DRAGON (VARANUS KOMODOENSIS) HDS 13 01062000 CRP2NCOSP LIZARD (CORDYLUS SPP.) HDS 14 01062000 CRP2NVASP LIZARD (VARANUS SPP.) HDS 15 01062000 CRP2NPHMA MADAGASCAR DAY GECKO (PHELSUMA MADAGASCARIENSIS) HDS 16 01062000 CRP0NGESP NON-CITES GECKO HDS 17 01062000 CRP0NLILI NON-CITES LIZARD HDS 18 01062000 CRP2NUROR ORNATE SPINY-TAILED LIZARD (UROMASTYX ORNATA) HDS 19 01062000 CRP2NCOZE PREHENSILE-TAILED SKINK (CORUCIA ZEBRATA) HDS 20 01062000 CRP1NCYCO RHINOCEROS IGUANA (CYCLURA CORNUTA) HDS 21 01062000 CRP2NTUSP TEGU SPECIES (TUPINAMBIS SPP.) HDS 22 01062000 CRP2NVASA WATER MONITOR (VARANUS SALVATOR) HDS 23 01062000 CRP1NBRFA FIJI BANDED IGUANA (BRACHYLOPHUS FASCIATUS) HDS 24 01062000 CRP2NDRGU GUYANAN CAIMAN LIZARD (DRACAENA GUIANENESIS) HDS 25 01062000 -

Potential Invasion Risk of Pet Traded Lizards, Snakes, Crocodiles

diversity Article Potential Invasion Risk of Pet Traded Lizards, Snakes, Crocodiles, and Tuatara in the EU on the Basis of a Risk Assessment Model (RAM) and Aquatic Species Invasiveness Screening Kit (AS-ISK) OldˇrichKopecký *, Anna Bílková, Veronika Hamatová, Dominika K ˇnazovická, Lucie Konrádová, Barbora Kunzová, Jana Slamˇeníková, OndˇrejSlanina, Tereza Šmídová and Tereza Zemancová Department of Zoology and Fisheries, Faculty of Agrobiology, Food and Natural Resources, Czech University of Life Sciences Prague, Kamýcká 129, Praha 6 - Suchdol 165 21, Prague, Czech Republic; [email protected] (A.B.); [email protected] (V.H.); [email protected] (D.K.); [email protected] (L.K.); [email protected] (J.S.); [email protected] (B.K.); [email protected] (O.S.); [email protected] (T.S.); [email protected] (T.Z.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +420-22438-2955 Received: 30 June 2019; Accepted: 9 September 2019; Published: 13 September 2019 Abstract: Because biological invasions can cause many negative impacts, accurate predictions are necessary for implementing effective restrictions aimed at specific high-risk taxa. The pet trade in recent years became the most important pathway for the introduction of non-indigenous species of reptiles worldwide. Therefore, we decided to determine the most common species of lizards, snakes, and crocodiles traded as pets on the basis of market surveys in the Czech Republic, which is an export hub for ornamental animals in the European Union (EU). Subsequently, the establishment and invasion potential for the entire EU was determined for 308 species using proven risk assessment models (RAM, AS-ISK). Species with high establishment potential (determined by RAM) and at the same time with high potential to significantly harm native ecosystems (determined by AS-ISK) included the snakes Thamnophis sirtalis (Colubridae), Morelia spilota (Pythonidae) and also the lizards Tiliqua scincoides (Scincidae) and Intellagama lesueurii (Agamidae). -

Annotated Checklist of the Recent and Extinct Pythons (Serpentes, Pythonidae), with Notes on Nomenclature, Taxonomy, and Distribution

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeysAnnotated 66: 29–79 (2010)checklist of the recent and extinct pythons (Serpentes, Pythonidae), with notes on... 29 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.66.683 CATALOGUE www.zookeys.org Launched to accelerate biodiversity research Annotated checklist of the recent and extinct pythons (Serpentes, Pythonidae), with notes on nomenclature, taxonomy, and distribution Wulf D. Schleip1, Mark O’Shea2,3 1 Fichtenweg 11, 53340 Meckenheim, Germany 2 Australian Venom Research Unit, Dept. Pharmacology, University of Melbourne, Vic., 3010, Australia 3 Reptile Department, West Midland Safari Park, Bewdley, Worcs., DY12 1LF, United Kingdom Corresponding authors : Wulf D. Schleip ( [email protected] ), Mark O’Shea ( [email protected] ) Academic editor: Hans-Dieter Sues | Received 11 December 2009 | Accepted 22 September 2010 | Published 4 November 2010 Citation: Schleip WD, O’Shea M (2010) Annotated checklist of the recent and extinct pythons (Serpentes, Pythonidae), with notes on nomenclature, taxonomy, and distribution. ZooKeys 66 : 29 – 79 . doi: 10.3897/zookeys.66.683 Abstract McDiarmid et al. (1999) published the fi rst part of their planned taxonomic catalog of the snakes of the world. Since then, several new python taxa have been described in both the scientifi c literature and non- peer-reviewed publications. Th is checklist evaluates the nomenclatural status of the names and discusses the taxonomic status of the new taxa, and aims to continue the work of McDiarmid et al. (1999) for the family Pythonidae, covering the period 1999 to 2010. Numerous new taxa are listed, and where appropri- ate recent synonymies are included and annotations are made. A checklist and a taxonomic identifi cation key of valid taxa are provided. -

Determination of the Phytochemical Properties of Oil Extracted from Meat of Python Bivittatus

IOSR Journal of Environmental Science, Toxicology and Food Technology (IOSR-JESTFT) e-ISSN: 2319-2402,p- ISSN: 2319-2399.Volume 13, Issue 11 Ser. I (November. 2019), PP 16-20 www.iosrjournals.org Determination of the Phytochemical Properties of Oil Extracted From Meat of Python Bivittatus 11Offurum, J.C.; 2Chukwu M.M.; 3Mbadike C.A.; 4Nwakaudu A.A.; 5Iheme C. 1,2,3,5Department of Chemical Engineering, Imo State Polytechnic, Umuagwo-Ohaji. 4Department of Food Science Technology, Federal University of Technology, Owerri. Abstract: This research work focused on the determination of the phytochemical properties of oil extracted from the meat of nonvenomous snake specie, ‘Python Bivittatus’, a Burmese Python, which is considered as sub- specie of the Python Molurus. Varying forms of snake (python) oils exist, with varying characteristics, each having different concentrations/strengths of activity. The python oil used for this study was collected from the extraction point at Umunnochi in Isukwuato L.G.A. of Abia State of Nigeria, where the dealers employed local (smoking) techniques to separate the oil from the meat of the already-dead python. The oil was subjected to centrifugation to remove inherent particulate matters. Phytochemical analysis (qualitatively and quantitative) were conducted on the oil sample, using the standard stipulated by the Association of Official Analytical Chemist (1997) as revised. The results of qualitative analysis showed that there is a little presence of alkaloids, tannis, and cardiac glycosides (+) in the sample; phenols indicated moderate presence (++), while saponins, Terpenoids, steroids and flavonoids showed heavy presence in the sample (+++). The quantitative analysis showed that tannins, saponins, alkaloids, flavonoids, phenol, steroids, terpenoids and cardiac glycosides were 61 .43%, 16.32%, 0.72%, 467.65µg/ml, 0.160mg/g, 5.91mg/100g, 206.08mg/100mg 82.40% respectively.