A Journal of Theory and Practice Fall 2016 (8:3)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Film Analysis Easy Rider - Focus on American Dream, Hippie Life Style and Soundtrack

Film Analysis Easy Rider - Focus on American Dream, Hippie Life Style and Soundtrack - Universität Augsburg Philologisch-Historische Fakultät Lehrstuhl für Amerikanistik PS: The 60s in Retrospect – A Magical History Tour Dozent: Udo Legner Sommersemester 2013 Referenten: Lisa Öxler, Marietta Braun, Tobias Berber Datum: 10.06.2013 Easy Rider – General Information ● Is a 1969 American road movie ● Written by Peter Fonda, Dennis Hopper, and Terry Southern ● Produced by Fonda and directed by Hopper ● Tells the story of two bikers (played by Fonda and Hopper) who travel through the American Southwest and South Easy Rider – General Information ● Success of Easy Rider helped spark the New Hollywood phase of filmmaking during the early 1970s ● Film was added to the Library of Congress National Registry in 1998 ● A landmark counterculture film, and a ”touchstone for a generation“ that ”captured the national imagination“ Easy Rider – General Information ● Easy Rider explores the societal landscape, issues, and tensions in the United States during the 1960s, such as the rise and fall of the hippie movement, drug use, and communal lifestyle ● Easy Rider is famous for its use of real drugs in its portrayal of marijuana and other substances Easy Rider - Plot ● Protagonists are two hippies in the USA of the 1970s: – Wyatt (Fonda), nicknamed "Captain America" dressed in American flag- adorned leather – Billy (Hopper) dressed in Native American-style buckskin pants and shirts and a bushman hat Easy Rider - Plot ● Character's names refer to Wyatt Earp and Billy the Kid ● The former is appreciative of help and of others, while the latter is often hostile and leery of outsiders. -

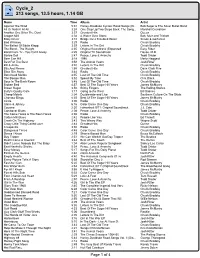

Cycle2 Playlist

Cycle_2 213 songs, 13.5 hours, 1.14 GB Name Time Album Artist Against The Wind 5:31 Harley-Davidson Cycles: Road Songs (Di... Bob Seger & The Silver Bullet Band All Or Nothin' At All 3:24 One Step Up/Two Steps Back: The Song... Marshall Crenshaw Another One Bites The Dust 3:37 Greatest Hits Queen Aragon Mill 4:02 A Water Over Stone Bok, Muir and Trickett Baby Driver 3:18 Bridge Over Troubled Water Simon & Garfunkel Bad Whiskey 3:29 Radio Chuck Brodsky The Ballad Of Eddie Klepp 3:39 Letters In The Dirt Chuck Brodsky The Band - The Weight 4:35 Original Soundtrack (Expanded Easy Rider Band From Tv - You Can't Alway 4:25 Original TV Soundtrack House, M.D. Barbie Doll 2:47 Peace, Love & Anarchy Todd Snider Beer Can Hill 3:18 1996 Merle Haggard Best For The Best 3:58 The Animal Years Josh Ritter Bill & Annie 3:40 Letters In The Dirt Chuck Brodsky Bits And Pieces 1:58 Greatest Hits Dave Clark Five Blow 'Em Away 3:44 Radio Chuck Brodsky Bonehead Merkle 4:35 Last Of The Old Time Chuck Brodsky The Boogie Man 3:52 Spend My Time Clint Black Boys In The Back Room 3:48 Last Of The Old Time Chuck Brodsky Broken Bed 4:57 Best Of The Sugar Hill Years James McMurtry Brown Sugar 3:50 Sticky Fingers The Rolling Stones Buffy's Quality Cafe 3:17 Going to the West Bill Staines Cheap Motels 2:04 Doublewide and Live Southern Culture On The Skids Choctaw Bingo 8:35 Best Of The Sugar Hill Years James McMurtry Circle 3:00 Radio Chuck Brodsky Claire & Johnny 6:16 Color Came One Day Chuck Brodsky Cocaine 2:50 Fahrenheit 9/11: Original Soundtrack J.J. -

Off the Beaten Track

Off the Beaten Track To have your recording considered for review in Sing Out!, please submit two copies (one for one of our reviewers and one for in- house editorial work, song selection for the magazine and eventual inclusion in the Sing Out! Resource Center). All recordings received are included in “Publication Noted” (which follows “Off the Beaten Track”). Send two copies of your recording, and the appropriate background material, to Sing Out!, P.O. Box 5460 (for shipping: 512 E. Fourth St.), Bethlehem, PA 18015, Attention “Off The Beaten Track.” Sincere thanks to this issue’s panel of musical experts: Richard Dorsett, Tom Druckenmiller, Mark Greenberg, Victor K. Heyman, Stephanie P. Ledgin, John Lupton, Angela Page, Mike Regenstreif, Seth Rogovoy, Ken Roseman, Peter Spencer, Michael Tearson, Theodoros Toskos, Rich Warren, Matt Watroba, Rob Weir and Sule Greg Wilson. that led to a career traveling across coun- the two keyboard instruments. How I try as “The Singing Troubadour.” He per- would have loved to hear some of the more formed in a variety of settings with a rep- unusual groupings of instruments as pic- ertoire that ranged from opera to traditional tured in the notes. The sound of saxo- songs. He also began an investigation of phones, trumpets, violins and cellos must the music of various utopian societies in have been glorious! The singing is strong America. and sincere with nary a hint of sophistica- With his investigation of the music of tion, as of course it should be, as the Shak- VARIOUS the Shakers he found a sect which both ers were hardly ostentatious. -

Imperialism and Exploration in the American Road Movie Andy Wright Pitzer College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Pitzer Senior Theses Pitzer Student Scholarship 2016 Off The Road: Imperialism And Exploration in the American Road Movie Andy Wright Pitzer College Recommended Citation Wright, Andy, "Off The Road: Imperialism And Exploration in the American Road Movie" (2016). Pitzer Senior Theses. Paper 75. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/pitzer_theses/75 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Pitzer Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pitzer Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Wright 1 OFF THE ROAD Imperialism And Exploration In The American Road Movie “Road movies are too cool to address serious socio-political issues. Instead, they express the fury and suffering at the extremities of a civilized life, and give their restless protagonists the false hope of a one-way ticket to nowhere.” –Michael Atkinson, quoted in “The Road Movie Book” (1). “‘Imperialism’ means the practice, the theory, and the attitudes of a dominating metropolitan center ruling a distant territory; ‘colonialism’, which is almost always a consequence of imperialism, is the implanting of settlements on distant territory” –Edward Said, Culture and Imperialism (9) “I am still a little bit scared of flying, but I am definitely far more scared of all the disgusting trash in between places” -Cy Amundson, This Is Not Happening “This is gonna be exactly like Eurotrip, except it’s not gonna suck” -Kumar Patel, Harold and Kumar Escape From Guantanamo Bay Wright 2 Off The Road Abstract: This essay explores the imperialist nature of the American road movie as it is defined by the film’s era of release, specifically through the lens of how road movies abuse the lands that are travelled through. -

BOB DYLAN 1966. Jan. 25. Columbia Recording Studios According to The

BOB DYLAN 1966. Jan. 25. Columbia Recording Studios According to the CD-2 “No Direction Home”, Michael Bloomfield plays the guitar intro and a solo later and Dylan plays the opening solo (his one and only recorded electric solo?) 1. “Leopard-skin Pill-box Hat” (6.24) (take 1) slow 2. “Leopard-skin Pill-box Hat” (3.58) Bloomfield solo 3. “Leopard-skin Pill-box Hat” (3.58) Dylan & Bloomfield guitar solo 4. “Leopard-skin Pill-box Hat” (6.23) extra verse On track (2) there is very fine playing from MB and no guitar solo from Uncle Bob, but a harmonica solo. 1966 3 – LP-2 “BLONDE ON BLONDE” COLUMBIA 1966? 3 – EP “BOB DYLAN” CBS EP 6345 (Portugal) 1987? 3 – CD “BLONDE ON BLONDE” CBS CDCBS 66012 (UK) 546 1992? 3 – CD “BOB DYLAN’S GREATEST HITS 2” COLUMBIA 471243 2 (AUT) 109 2005 1 – CD-2 “NO DIRECTION HOME – THE SOUNDTRACK” THE BOOTLEG SERIES VOL. 7 - COLUMBIA C2K 93937 (US) 529 Alternate take 1 2005 1 – CD-2 “NO DIRECTION HOME – THE SOUNDTRACK” THE BOOTLEG SERIES VOL. 7 – COL 520358-2 (UK) 562 Alternate take 1 ***** Febr. 4.-11, 1966 – The Paul Butterfield Blues Band at Whiskey a Go Go, LA, CA Feb. 25, 1966 – Butterfield Blues Band -- Fillmore ***** THE CHICAGO LOOP 1966 Prod. Bob Crewe and Al Kasha 1,3,4 - Al Kasha 2 Judy Novy, vocals, percussion - Bob Slawson, vocals, rhythm guitar - Barry Goldberg, organ, piano - Carmine Riale, bass - John Siomos, drums - Michael Bloomfield, guitar 1 - John Savanno, guitar, 2-4 1. "(When She Wants Good Lovin') She Comes To Me" (2.49) 1a. -

EASY RIDER Stars and Stripes Teardrop Tank, Fifty Years After the ‘Pullquote, Gleaming in the Californian Sun, I Was Austin on My Imaginary “Chopper” with Him

6 *** Sunday 24 November 2019 The Sunday Telegraph USA ‘Along the Loop Road, I felt the pure joy of biking’ EASY RIDER stars and stripes teardrop tank, Fifty years after the ‘Pullquote, gleaming in the Californian sun, I was Austin on my imaginary “chopper” with him. release of the classic Technically, the movie starts in Los deck light Angeles, as our banditos head for Mardi Gras in New Orleans, 2,000 film,Chris Coplans 16pt on miles (3,200km) away. However, the 16pt. movie kick-starts 300 miles (480km) jumps on to a Harley further east in Needles, California Pullquote, where the credits roll to the driving and hits Route 66 beat of Steppenwolf ’s classic Born To Austin Be Wild. I headed to Needles on my didn’t do no drug deal, modern Harley Davidson Sportster smoke weed or drop deck light from Las Vegas, a much shorter and acid. Nor did I visit a 16pt on easier ride than from LA. Those brothel. But I did ride a pulsating opening credits were filmed Harley Davidson from 16pt’ along Route 66 between Needles and the Californian desert to Flagstaff, a rip-roaring 200-mile the bayous of southern (320km) ride to the east. I gunned my I Louisiana. When Easy Harley into action and with a twist of Rider burst onto our screens 50 years the throttle and a rumble of the 1200cc ALLSTAR/COLUMBIA ago, the super cool “Captain V-twin engine, followed in their America” Peter Fonda (Wyatt) and counterculture tyre tracks. the crazed Denis Hopper (Billy) did Route 66 climbs, winds and snakes THE BIKES all of the above and, according to its way through canyons and valleys, legend, much more. -

Movie in Search of America: the Rhetoric of Myth in Easy Rider

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 2005 Movie in search of America: The rhetoric of myth in Easy Rider Hayley Susan Raynes Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the American Film Studies Commons, and the Rhetoric Commons Recommended Citation Raynes, Hayley Susan, "Movie in search of America: The rhetoric of myth in Easy Rider" (2005). Theses Digitization Project. 2804. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/2804 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MOVIE IN SEARCH OF AMERICA: THE RHETORIC OF MYTH IN EASY RIDER A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in English Composition by Hayley Susan Raynes March 2005 MOVIE IN SEARCH OF AMERICA: THE RHETORIC OF MYTH IN EASY RIDER A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino' by Hayley Susan Raynes March 2005 © 2005 Hayley Susan Raynes ABSTRACT Chronicling the cross-country journey of two hippies on motorcycles, Easy Rider is an historical fiction embodying the ideals, naivete, politics and hypocrisies of 1960's America. This thesis is a rhetorical analysis of Easy Rider exploring how auteurs Peter Fonda, Dennis Hopper and Terry Southern's use of road, regional and cowboy mythology creates a text that simultaneously exposes and is dominated by the ironies inherent in American culture while breathing new life into the cowboy myth and reaffirming his place as one of America's most enduring cultural icons. -

Preproduction (1967) Production (Feb- April 1968) Post-Production

Easy Rider: Circumstances of Production The Berra chapter assigned for 4/7 describes in detail the production of Easy Rider, noting that some elements of the filmmaking process remain ambiguous due to competing stories from director Dennis Hopper, star Peter Fonda, and writer Terry Southern. Nevertheless, I wanted to offer an outline of the film’s circumstances of production and list stylistic features to watch for as you screen Easy Rider. You should also review the questions for Thursday’s electronic response before you view the film. Production Timeline Preproduction Post-Production (1967) (1968-1969) • Hopper produces •Peter Fonda Production (Feb- develops idea for various long edits Easy Rider after April 1968) of film (2.75-5 hrs) viewing MPAA exhibit • Mardi Gras scenes • Executive (and filmed prior to producer Bert drinking/smoking rest, with 16 mm Schneider forces pot) in Toronto while Hopper on promoting The Trip camera and on location in New vacation, then has •Fonda contacts editor Donn friend Dennis Hopper Orleans with and pair decides to actors Fonda, Cambern recut collaborate, with Hopper, Black and film to marketable Fonda as producer Basil length and Hopper as • Shoot unorganized • Raybert makes director and drug-fueled, distribution deal •Writer Terry with problems with Columbia Southern and developing • Easy Rider collaborates with between Hopper premieres 14 July Fonda on story and Fonda 1969 in New York treatment (later lawsuits between • Crew returns to City and earns Hopper and LA, where other $19,000,000 Southern) -

Whats Purple and Goes Buzz Buzz?: a Conversation with the Electric Prunes’ James Lowe

A Quinn Martin Production Subscribe to feed ABOUT Whats Purple and Goes Buzz Buzz?: A Conversation with The Electric Prunes’ James Lowe Sam Tweedle: The Electric Prunes are one of the great 60’s groups that sat on the fringes of SAM TWEEDLE – THE POP CULTURE ADDICT the rock n’ roll scene. Sam Tweedle is a writer and pop James Lowe: Well, I was culture addict who has been surprised that anybody knew entertaining and educating fans of about us when we came back the pop culture journey for a decade. and started playing again. His writing has been featured in The National Post, CNN.com, and Sam: Really? Why is that? Filmfax magazine. James: I think essentially THE POP CULTURE ADDICT AND because the people that we were FRIENDS! involved with made us feel that what we did, when we did it, was Visit the gallery to see more photos a failure. So I never admitted that of Sam Tweedle and his close I was in The Electric Prunes for a encounters! lot of years. [The label] expected us to be like The Beatles and sell a lot of records, but we didn’t do “I was surprised that anybody knew about us when we came that. I’m kind of surprised that we back and started playing again…. I never admitted that I was have fans. in The Electric Prunes for a lot of years.” Sam: Well I always put The Electric Prunes in the same league with some of the era’s cult favourites, like The Velvet Underground or The New Colony Six. -

Exploring Postcolonial Themes in the American Road Movie Andy Wright Pitzer College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Pitzer Senior Theses Pitzer Student Scholarship 2016 Off the Road: Exploring Postcolonial Themes in the American Road Movie Andy Wright Pitzer College Recommended Citation Wright, Andy, "Off the Road: Exploring Postcolonial Themes in the American Road Movie" (2016). Pitzer Senior Theses. Paper 67. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/pitzer_theses/67 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Pitzer Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pitzer Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Wright 1 OFF THE ROAD Exploring Postcolonial Themes in the American Road Movie “Road movies are too cool to address serious socio-political issues. Instead, they express the fury and suffering at the extremities of a civilized life, and give their restless protagonists the false hope of a one-way ticket to nowhere.” –Michael Atkinson, quoted in “The Road Movie Book” (1). “This is gonna be exactly like Eurotrip, except it’s not gonna suck.” –Kumar Patel, “Harold and Kumar Escape from Guantanamo Bay” Wright 2 Off the Road: Exploring Postcolonial Themes in the American Road Movie Abstract: This essay explores the colonial nature of the American road movie, specifically through the lens of how road movies treat the South according to Stuart Hall’s concepts of identity and Edward Said’s on Othering and the colonial gaze. To accomplish this, the essay analyzes the classic 1969 road movie, “Easy Rider”, and the more contemporary parody from 2008, “Harold and Kumar Escape from Guantanamo Bay.” The thrust of this paper becomes: if a progressive parody of road movies cannot escape the trappings of colonialism “Easy Rider” displays, perhaps the road movie itself is flawed. -

Easy Rider Filmmusikanalyse

Easy Rider Filmmusikanalyse Hausarbeit im Masterstudiengang Audiovisuelle Medien, Schwerpunkt Ton im Modul „Komposition und Film“ (253082a) vorgelegt von Marcel Remy Matr.-Nr.: 37445 am 31. Juli 2019 Dozent: Professor Oliver Curdt Inhaltsverzeichnis II Inhaltsverzeichnis Inhaltsverzeichnis ...................................................................................................... II 1 Fakten zum Film ................................................................................................. 1 2 Handlung ............................................................................................................ 2 3 Relevanz des Films .............................................................................................. 3 4 Die Charaktere ................................................................................................... 4 4.1 Wyatt/Captain America ............................................................................... 4 4.2 Billy ............................................................................................................. 4 4.3 Jesus ............................................................................................................ 5 4.4 George Hanson ............................................................................................ 5 5 Soundtrack-Analyse ............................................................................................ 6 5.1 Techniken und Besonderheiten ................................................................... 6 5.2 -

Chapter Five “Days of Future Passed”

Chapter Five “Days of Future Passed” Chapter 5 Overview The Beatles Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967) was a dramatic departure from previous rock music. No longer restricted to teenage dance music, the Sgt. Pepper album ushered in a period of music for listening or "album oriented rock" (AOR) Classic concept albums such as Days of Future Passed by the Moody Blues used orchestral settings and Pink Floyd employed electronic experimentation and the elements of the avant garde. Rock musicals such as Hair, (1967) and rock operas such as Tommy, (1968) elevated rock music to a much higher artistic level. In general, pieces become longer, more complex and experimental often using electronic music, noise, and non-western musical idioms. The hippie subculture's emphasis on visual and musical diversity encouraged rock to splinter into many sub-styles such as heavy metal, glitter/glam, progressive rock, and theatre rock. 1 The End of the Hippie Counter-Culture Movement By 1970, signs that the hippie counterculture was declining became apparent. 1. During a ten month period rock lost three of its legends: Jimi Hendrix, September 18, 1970; Janis Joplin October 4, 1970; and Jim Morrison July 3, 1971 all the result of drug related causes. 2. In 1970 four anti-war protesters were shot to death by National Guardsmen at Kent State University. Most universities were shut down in the resulting nationwide campus protests. Kent State effectively brought to an end the free speech movement at American Universities. 3. The Beatles, in many ways the spokesmen of the counterculture, broke up in 1970.