Exploring Postcolonial Themes in the American Road Movie Andy Wright Pitzer College

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Film Analysis Easy Rider - Focus on American Dream, Hippie Life Style and Soundtrack

Film Analysis Easy Rider - Focus on American Dream, Hippie Life Style and Soundtrack - Universität Augsburg Philologisch-Historische Fakultät Lehrstuhl für Amerikanistik PS: The 60s in Retrospect – A Magical History Tour Dozent: Udo Legner Sommersemester 2013 Referenten: Lisa Öxler, Marietta Braun, Tobias Berber Datum: 10.06.2013 Easy Rider – General Information ● Is a 1969 American road movie ● Written by Peter Fonda, Dennis Hopper, and Terry Southern ● Produced by Fonda and directed by Hopper ● Tells the story of two bikers (played by Fonda and Hopper) who travel through the American Southwest and South Easy Rider – General Information ● Success of Easy Rider helped spark the New Hollywood phase of filmmaking during the early 1970s ● Film was added to the Library of Congress National Registry in 1998 ● A landmark counterculture film, and a ”touchstone for a generation“ that ”captured the national imagination“ Easy Rider – General Information ● Easy Rider explores the societal landscape, issues, and tensions in the United States during the 1960s, such as the rise and fall of the hippie movement, drug use, and communal lifestyle ● Easy Rider is famous for its use of real drugs in its portrayal of marijuana and other substances Easy Rider - Plot ● Protagonists are two hippies in the USA of the 1970s: – Wyatt (Fonda), nicknamed "Captain America" dressed in American flag- adorned leather – Billy (Hopper) dressed in Native American-style buckskin pants and shirts and a bushman hat Easy Rider - Plot ● Character's names refer to Wyatt Earp and Billy the Kid ● The former is appreciative of help and of others, while the latter is often hostile and leery of outsiders. -

Jimi Hendrix and the Raconteurs to Rock Guitar Hero(R) World Tour in November

Jimi Hendrix and The Raconteurs to Rock Guitar Hero(R) World Tour in November SANTA MONICA, Calif., Oct 28, 2008 /PRNewswire-FirstCall via COMTEX News Network/ -- The Raconteurs and Jimi Hendrix will both take to the virtual stage this November as downloadable content in Activision Publishing, Inc.'s (Nasdaq: ATVI) Guitar Hero(R) World Tour, the company announced today. Already confirmed to take center stage as a playable character, Jimi Hendrix, one of the most creative and influential musicians of the 20th century, will return with three additional downloadable master tracks. The blues track "If 6 was 9," rhythm and blues classic "Little Wing," and a live version of the iconic Hendrix track "Fire" will all be available as downloadable content for Guitar Hero World Tour on November 13th, 2008. Making their debut appearance in a videogame, charismatic rockers, The Raconteurs are set to leave their mark with three tracks off their second album Consolers of the Lonely. The trio of "Salute Your Solution," "Hold Up" and "Consoler of the Lonely" will debut as part of a three song set list on November 20th, 2008 that will allow virtual rockers the chance to experience the killer sounds of The Raconteurs like never before. The Raconteurs Track Pack and Jimi Hendrix Track Pack will be available on Xbox LIVE(R) Marketplace for Xbox 360(R) video game and entertainment system from Microsoft for 440 Microsoft Points and on the PLAYSTATION(R)Store for the PLAYSTATION(R)3 computer entertainment system for $5.49. In addition, the three tracks from The Raconteurs Track Pack will be released as single downloadable songs for Xbox 360 for 160 Microsoft Points, PLAYSTATION 3 system for $1.99 and Nintendo(R) Wi-Fi Connection for Wii(TM) for 200 Wii Points. -

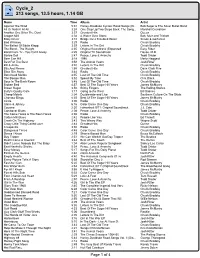

Cycle2 Playlist

Cycle_2 213 songs, 13.5 hours, 1.14 GB Name Time Album Artist Against The Wind 5:31 Harley-Davidson Cycles: Road Songs (Di... Bob Seger & The Silver Bullet Band All Or Nothin' At All 3:24 One Step Up/Two Steps Back: The Song... Marshall Crenshaw Another One Bites The Dust 3:37 Greatest Hits Queen Aragon Mill 4:02 A Water Over Stone Bok, Muir and Trickett Baby Driver 3:18 Bridge Over Troubled Water Simon & Garfunkel Bad Whiskey 3:29 Radio Chuck Brodsky The Ballad Of Eddie Klepp 3:39 Letters In The Dirt Chuck Brodsky The Band - The Weight 4:35 Original Soundtrack (Expanded Easy Rider Band From Tv - You Can't Alway 4:25 Original TV Soundtrack House, M.D. Barbie Doll 2:47 Peace, Love & Anarchy Todd Snider Beer Can Hill 3:18 1996 Merle Haggard Best For The Best 3:58 The Animal Years Josh Ritter Bill & Annie 3:40 Letters In The Dirt Chuck Brodsky Bits And Pieces 1:58 Greatest Hits Dave Clark Five Blow 'Em Away 3:44 Radio Chuck Brodsky Bonehead Merkle 4:35 Last Of The Old Time Chuck Brodsky The Boogie Man 3:52 Spend My Time Clint Black Boys In The Back Room 3:48 Last Of The Old Time Chuck Brodsky Broken Bed 4:57 Best Of The Sugar Hill Years James McMurtry Brown Sugar 3:50 Sticky Fingers The Rolling Stones Buffy's Quality Cafe 3:17 Going to the West Bill Staines Cheap Motels 2:04 Doublewide and Live Southern Culture On The Skids Choctaw Bingo 8:35 Best Of The Sugar Hill Years James McMurtry Circle 3:00 Radio Chuck Brodsky Claire & Johnny 6:16 Color Came One Day Chuck Brodsky Cocaine 2:50 Fahrenheit 9/11: Original Soundtrack J.J. -

Why Call Them "Cult Movies"? American Independent Filmmaking and the Counterculture in the 1960S Mark Shiel, University of Leicester, UK

Why Call them "Cult Movies"? American Independent Filmmaking and the Counterculture in the 1960s Mark Shiel, University of Leicester, UK Preface In response to the recent increased prominence of studies of "cult movies" in academic circles, this essay aims to question the critical usefulness of that term, indeed the very notion of "cult" as a way of talking about cultural practice in general. My intention is to inject a note of caution into that current discourse in Film Studies which valorizes and celebrates "cult movies" in particular, and "cult" in general, by arguing that "cult" is a negative symptom of, rather than a positive response to, the social, cultural, and cinematic conditions in which we live today. The essay consists of two parts: firstly, a general critique of recent "cult movies" criticism; and, secondly, a specific critique of the term "cult movies" as it is sometimes applied to 1960s American independent biker movies -- particularly films by Roger Corman such as The Wild Angels (1966) and The Trip (1967), by Richard Rush such as Hell's Angels on Wheels (1967), The Savage Seven, and Psych-Out (both 1968), and, most famously, Easy Rider (1969) directed by Dennis Hopper. Of course, no-one would want to suggest that it is not acceptable to be a "fan" of movies which have attracted the label "cult". But this essay begins from a position which assumes that the business of Film Studies should be to view films of all types as profoundly and positively "political", in the sense in which Fredric Jameson uses that adjective in his argument that all culture and every cultural object is most fruitfully and meaningfully understood as an articulation of the "political unconscious" of the social and historical context in which it originates, an understanding achieved through "the unmasking of cultural artifacts as socially symbolic acts" (Jameson, 1989: 20). -

Summer Classic Film Series, Now in Its 43Rd Year

Austin has changed a lot over the past decade, but one tradition you can always count on is the Paramount Summer Classic Film Series, now in its 43rd year. We are presenting more than 110 films this summer, so look forward to more well-preserved film prints and dazzling digital restorations, romance and laughs and thrills and more. Escape the unbearable heat (another Austin tradition that isn’t going anywhere) and join us for a three-month-long celebration of the movies! Films screening at SUMMER CLASSIC FILM SERIES the Paramount will be marked with a , while films screening at Stateside will be marked with an . Presented by: A Weekend to Remember – Thurs, May 24 – Sun, May 27 We’re DEFINITELY Not in Kansas Anymore – Sun, June 3 We get the summer started with a weekend of characters and performers you’ll never forget These characters are stepping very far outside their comfort zones OPENING NIGHT FILM! Peter Sellers turns in not one but three incomparably Back to the Future 50TH ANNIVERSARY! hilarious performances, and director Stanley Kubrick Casablanca delivers pitch-dark comedy in this riotous satire of (1985, 116min/color, 35mm) Michael J. Fox, Planet of the Apes (1942, 102min/b&w, 35mm) Humphrey Bogart, Cold War paranoia that suggests we shouldn’t be as Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin (1968, 112min/color, 35mm) Charlton Heston, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad worried about the bomb as we are about the inept Glover . Directed by Robert Zemeckis . Time travel- Roddy McDowell, and Kim Hunter. Directed by Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre. -

Off the Beaten Track

Off the Beaten Track To have your recording considered for review in Sing Out!, please submit two copies (one for one of our reviewers and one for in- house editorial work, song selection for the magazine and eventual inclusion in the Sing Out! Resource Center). All recordings received are included in “Publication Noted” (which follows “Off the Beaten Track”). Send two copies of your recording, and the appropriate background material, to Sing Out!, P.O. Box 5460 (for shipping: 512 E. Fourth St.), Bethlehem, PA 18015, Attention “Off The Beaten Track.” Sincere thanks to this issue’s panel of musical experts: Richard Dorsett, Tom Druckenmiller, Mark Greenberg, Victor K. Heyman, Stephanie P. Ledgin, John Lupton, Angela Page, Mike Regenstreif, Seth Rogovoy, Ken Roseman, Peter Spencer, Michael Tearson, Theodoros Toskos, Rich Warren, Matt Watroba, Rob Weir and Sule Greg Wilson. that led to a career traveling across coun- the two keyboard instruments. How I try as “The Singing Troubadour.” He per- would have loved to hear some of the more formed in a variety of settings with a rep- unusual groupings of instruments as pic- ertoire that ranged from opera to traditional tured in the notes. The sound of saxo- songs. He also began an investigation of phones, trumpets, violins and cellos must the music of various utopian societies in have been glorious! The singing is strong America. and sincere with nary a hint of sophistica- With his investigation of the music of tion, as of course it should be, as the Shak- VARIOUS the Shakers he found a sect which both ers were hardly ostentatious. -

2010 Palm Beach International Film Festival April 22-26, 2010 Winner of Platinum Clubs of America 5 Star Award

Palm Beach International Designed by:Designed Kevin Manger Cobb Theatres are proud sponsors of the Palm Beach International Film Festival Cobb Theatres: K Art & Independent Films K Metropolitan Opera Live Events K Fathom Special Events K 3-D Capability K Online Ticketing Available K All Stadium Seating K Digital Projection and Sound Downtown at Jupiter the Gardens 16 Stadium 18 www.CobbTheatres.com Downtown at the Gardens 16 | 11701 Lake Victoria Gardens Ave. | Palm Beach Gardens, Florida | 561.253.1444 Jupiter Stadium 18 | 201 North US Highway 1 | Jupiter, Florida | 561.747.7333 The City of Boca Raton is proud to support the 2010 Palm Beach International Film Festival April 22-26, 2010 Winner of Platinum Clubs of America 5 Star Award Boca West...Still the Best • For Quality of Membership • A Sense of Tradition #1 Country Club in the State of Florida • First Class Amenities #1 Residential Country Club in the United States • Quality of Management & Staff 20588 Boca West Drive, Boca Raton, FL 33434 561.488.6990 www.bocawestcc.org Live The Life...We Can Make It Happen! Travel Services ® Representative LET OUR CENTURY OF EXPERIENCE AND HIGHLY PERSONALIZED SERVICE BE YOUR PASSPORT For The Best Times In Your Life www.fugazytravel.com 6006 SW 18th Street, Suite B-3, Boca Raton, FL 33433 561.447.7555 800.852.7613 M-F 9:00am – 5:30pm PALM BEACH INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVALWelcomeWELCOME DEAR FRIENDS, Welcome to the 15th Anniversary of the Palm Beach International Film Festival. It is truly a privilege for me to celebrate this momentous accomplishment! I have been honored to have led this prestigious organization over the past six years and been involved since the beginning. -

Dennis Hopper

GALERIE THADDAEUS ROPAC DENNIS HOPPER ICONS OF THE SIXTIES PARIS PANTIN 21 Oct 2015 - 27 Feb 2016 OPENING: WEDNESDAY, 21 OCTOBER 2015, 7PM-9PM Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac Paris Pantin is delighted to present Dennis Hopper’s exhibition Icons of the Sixties, a selection of photographs and personal objects alongside an emblematic sculpture as well as an installation composed of two canvases and an experimental film. The multitalented actor, director, photographer and painter Dennis Hopper (1936 – 2010) was known as an icon of the New Hollywood and of the artistic underground in California. In his early age he started as an actor alongside James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause (1955), working within the traditional Hollywood studio system, yet he felt driven to other artistic fields. Dean advised him to pick up a photo camera to investigate new creative territories. At this time Hopper painted a lot, “influenced by abstract expressionism and jazz” as he said, but after a fire devastated his house in Bel Air in 1961 and destroyed almost all his paintings, he stopped painting and turned more and more to photography. In the following years he always walked around with a camera, as a chronicler of his time, eager to capture the cultural and social seism that hit the American way of life specifically on the West coast – with its revolutionary wave of beat, pop and art. At the centre of the exhibition in Paris Pantin we present a selection of hand-signed vintage photographic prints by Dennis Hopper where he experimented with an irregular black frame produced by the photo-emulsion. -

Photographs by Dennis Hopper

G A G O S I A N G A L L E R Y 9 September 2014 PRESS RELEASE GAGOSIAN GALLERY VIA FRANCESCO CRISPI 16 T. +39.06.4208.6498 00187 ROME F. +39.06.4201.4765 GALLERY HOURS: Tue–Sat: 10:30am–7:00pm and by appointment SCRATCHING THE SURFACE: Photographs by Dennis Hopper Tuesday, 23 September–Saturday, 8 November 2014 Opening reception: Tuesday, September 23rd, from 6:00 to 8:00pm This is a story of a man/child who chose to develop his five senses and live and experience rather than just read. —Dennis Hopper Gagosian Rome is pleased to announce an exhibition of the late Dennis Hopper’s photographs of the 1960s, together with the Drugstore Camera series of the early 1970s and continuous screenings of his films and interviews. This will be the first major exhibition of Hopper's work in Rome. Hopper established his reputation as a cult actor and director with Easy Rider (1969), and maintained this status with gritty performances in The American Friend (1977), Apocalypse Now (1979), Blue Velvet (1986), Hoosiers (1986), and as director of Colors (1988). During his rise to Hollywood stardom, he captured the establishment-busting spirit of the 1960s in photographs that travel from Los Angeles to Harlem to Tijuana, Mexico, and which portray iconic figures including Jane Fonda, Andy Warhol, and John Wayne. Spontaneous portraits of now-legendary artists, actors, and musicians are among a selection of nearly one hundred signed vintage prints. Claes Oldenburg appears at a wedding, standing among plaster cake slices that he created as party favors, plated and placed in uniform rows on the ground. -

Imperialism and Exploration in the American Road Movie Andy Wright Pitzer College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Pitzer Senior Theses Pitzer Student Scholarship 2016 Off The Road: Imperialism And Exploration in the American Road Movie Andy Wright Pitzer College Recommended Citation Wright, Andy, "Off The Road: Imperialism And Exploration in the American Road Movie" (2016). Pitzer Senior Theses. Paper 75. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/pitzer_theses/75 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Pitzer Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pitzer Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Wright 1 OFF THE ROAD Imperialism And Exploration In The American Road Movie “Road movies are too cool to address serious socio-political issues. Instead, they express the fury and suffering at the extremities of a civilized life, and give their restless protagonists the false hope of a one-way ticket to nowhere.” –Michael Atkinson, quoted in “The Road Movie Book” (1). “‘Imperialism’ means the practice, the theory, and the attitudes of a dominating metropolitan center ruling a distant territory; ‘colonialism’, which is almost always a consequence of imperialism, is the implanting of settlements on distant territory” –Edward Said, Culture and Imperialism (9) “I am still a little bit scared of flying, but I am definitely far more scared of all the disgusting trash in between places” -Cy Amundson, This Is Not Happening “This is gonna be exactly like Eurotrip, except it’s not gonna suck” -Kumar Patel, Harold and Kumar Escape From Guantanamo Bay Wright 2 Off The Road Abstract: This essay explores the imperialist nature of the American road movie as it is defined by the film’s era of release, specifically through the lens of how road movies abuse the lands that are travelled through. -

Janette Cohen Scalie Redoctane +46 (0)8 44 18 615 [email protected]

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE For media inquiries, please contact: Janette Cohen Scalie RedOctane +46 (0)8 44 18 615 [email protected] GUITAR HERO® CATALOG EXPANDS WITH NEW MUSIC FROM ROCK ‘N’ ROLL ICONS QUEEN AND JIMI HENDRIX THIS MONTH Six Additional Tracks from Countries throughout Europe and the James Bond Theme Song Further Add to Guitar Hero World Tour’s Downloadable Content Set List SANTA MONICA, CA – March 3, 2009 – This month, gamers will again be able to expand their virtual set lists with over a dozen new downloadable tracks for Activision Publishing, Inc.’s (Nasdaq: ATVI) Guitar Hero® World Tour. With over 37 million songs downloaded for the franchise to date, Guitar Hero® fans will soon be able to experience more awesome music – from the likes of English rock ‘n’ roll icons Queen, guitar legend Jimi Hendrix, a host of European superstars and more – which will join the more than 550 songs rocking the Guitar Hero catalog already. On March 5th, Guitar Hero World Tour’s global music library will continue to grow with three additional tracks from some of Europe’s greatest bands. The third European Track Pack, which includes the hit song “Break It Out” by Italian pop punk band Vanilla Sky and “In the Shadows” by one of Finland’s most successful bands, The Rasmus, will also contain “Cʹest Comme Ça” the top single from French pop rock duo Les Rita Mitsouko’s 1986 album The No Comprendo. As a follow‐up to the third European Track Pack, rockers from the Netherlands, Germany and Spain will also be contributing to Guitar Hero World Tour’s increasing catalog of downloadable content. -

BOB DYLAN 1966. Jan. 25. Columbia Recording Studios According to The

BOB DYLAN 1966. Jan. 25. Columbia Recording Studios According to the CD-2 “No Direction Home”, Michael Bloomfield plays the guitar intro and a solo later and Dylan plays the opening solo (his one and only recorded electric solo?) 1. “Leopard-skin Pill-box Hat” (6.24) (take 1) slow 2. “Leopard-skin Pill-box Hat” (3.58) Bloomfield solo 3. “Leopard-skin Pill-box Hat” (3.58) Dylan & Bloomfield guitar solo 4. “Leopard-skin Pill-box Hat” (6.23) extra verse On track (2) there is very fine playing from MB and no guitar solo from Uncle Bob, but a harmonica solo. 1966 3 – LP-2 “BLONDE ON BLONDE” COLUMBIA 1966? 3 – EP “BOB DYLAN” CBS EP 6345 (Portugal) 1987? 3 – CD “BLONDE ON BLONDE” CBS CDCBS 66012 (UK) 546 1992? 3 – CD “BOB DYLAN’S GREATEST HITS 2” COLUMBIA 471243 2 (AUT) 109 2005 1 – CD-2 “NO DIRECTION HOME – THE SOUNDTRACK” THE BOOTLEG SERIES VOL. 7 - COLUMBIA C2K 93937 (US) 529 Alternate take 1 2005 1 – CD-2 “NO DIRECTION HOME – THE SOUNDTRACK” THE BOOTLEG SERIES VOL. 7 – COL 520358-2 (UK) 562 Alternate take 1 ***** Febr. 4.-11, 1966 – The Paul Butterfield Blues Band at Whiskey a Go Go, LA, CA Feb. 25, 1966 – Butterfield Blues Band -- Fillmore ***** THE CHICAGO LOOP 1966 Prod. Bob Crewe and Al Kasha 1,3,4 - Al Kasha 2 Judy Novy, vocals, percussion - Bob Slawson, vocals, rhythm guitar - Barry Goldberg, organ, piano - Carmine Riale, bass - John Siomos, drums - Michael Bloomfield, guitar 1 - John Savanno, guitar, 2-4 1. "(When She Wants Good Lovin') She Comes To Me" (2.49) 1a.