Sibbald Creek: a Record of 11,000 Years Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vernon & District Family History Society Library Catalogue

Vernon & District Family History Society Library Catalogue Location Title Auth. Last Notes Magazine - American Ancestors 4 issues. A local history book and is a record of the pioneer days of the 80 Years of Progress (Westlock, AB Committee Westlock District. Many photos and family stories. Family Alberta) name index. 929 pgs History of Kingman and Districts early years in the 1700s, (the AB A Harvest of Memories Kingman native peoples) 1854 the Hudson Bay followed by settlers. Family histories, photographs. 658 pgs Newspapers are arranged under the place of publication then under chronological order. Names of ethnic newspapers also AB Alberta Newspapers 1880 - 1982 Strathern listed. Photos of some of the newspapers and employees. 568 pgs A history of the Lyalta, Ardenode, Dalroy Districts. Contains AB Along the Fireguard Trail Lyalta photos, and family stories. Index of surnames. 343 pgs A local history book on a small area of northwestern Alberta from Flying Shot to South Wapiti and from Grovedale to AB Along the Wapiti Society Klondyke Trail. Family stories and many photos. Surname index. 431 pgs Alberta, formerly a part of the North-West Territories. An An Index to Birth, Marriage & Death AB Alberta index to Birth, Marriage and Death Registrations prior to Registrations prior to 1900 1900. 448 pgs AB Ann's Story Clifford The story of Pat Burns and his ranching empire. History of the Lower Peace River District. The contribution of AB Around the Lower Peace Gordon the people of Alberta, through Alberta Culture, acknowledged. 84 pgs Illustrated Starting with the early settlers and homesteaders, up to and AB As The Years Go By... -

2010 Final Receipt Point Rates: ($/103M3/Month, Except IT Which Is $/103M3/D) Effective from November 1, 2010

Summary of 2010 Final Receipt Point Rates: ($/103m3/month, except IT which is $/103m3/d) Effective from November 1, 2010 Average Receipt Price: 207.61 Receipt Price Floor: 121.71 Receipt Price Ceiling: 293.51 Point C Point B Point A Premium/Discount: 105% 100% 95% 110% 115% FT-RN PRICE 1 Year FT-R PRICE FT-R PRICE FT-R PRICE Non- Station Station 1 to < 3 3 to < 5 > 5 Renewable IT-R Project Number Station Name Mnemonic Year Term Year Term Year Term Firm PRICE Area 1001 BINDLOSS SOUTH BINDS 127.80 121.71 115.62 133.88 4.60 NE 1002 BINDLOSS N. #1 BINN1 127.80 121.71 115.62 133.88 4.60 NE 1003 PROVOST NORTH PROVN 192.21 183.06 173.91 201.37 6.92 NE 1004 CESSFORD WARDLO CEWRD 127.80 121.71 115.62 133.88 4.60 NE 1007 OYEN OYNXX 158.34 150.80 143.26 165.88 5.70 NE 1008 SIBBALD SIBBD 205.07 195.30 185.54 214.83 7.38 ML 1009 ATLEE-BUFFALO ATBUF 127.80 121.71 115.62 133.88 4.60 ML 1010 PRINCESS-DENHAR PRNDT 127.80 121.71 115.62 133.88 4.60 ML 1012 CESSFORD WEST CESFW 127.80 121.71 115.62 133.88 4.60 NE 1013 PROVOST SOUTH PROVS 209.54 199.56 189.58 219.52 7.55 NE 1015 COUNTESS MAKEPEACE CONTM 127.80 121.71 115.62 133.88 4.60 ML 1016 HUSSAR-CHANCELL HUCHA 127.80 121.71 115.62 133.88 4.60 ML 1017 MED HAT N. -

Specialized and Rural Municipalities and Their Communities

Specialized and Rural Municipalities and Their Communities Updated December 18, 2020 Municipal Services Branch 17th Floor Commerce Place 10155 - 102 Street Edmonton, Alberta T5J 4L4 Phone: 780-427-2225 Fax: 780-420-1016 E-mail: [email protected] SPECIALIZED AND RURAL MUNICIPALITIES AND THEIR COMMUNITIES MUNICIPALITY COMMUNITIES COMMUNITY STATUS SPECIALIZED MUNICIPALITES Crowsnest Pass, Municipality of None Jasper, Municipality of None Lac La Biche County Beaver Lake Hamlet Hylo Hamlet Lac La Biche Hamlet Plamondon Hamlet Venice Hamlet Mackenzie County HIGH LEVEL Town RAINBOW LAKE Town Fort Vermilion Hamlet La Crete Hamlet Zama City Hamlet Strathcona County Antler Lake Hamlet Ardrossan Hamlet Collingwood Cove Hamlet Half Moon Lake Hamlet Hastings Lake Hamlet Josephburg Hamlet North Cooking Lake Hamlet Sherwood Park Hamlet South Cooking Lake Hamlet Wood Buffalo, Regional Municipality of Anzac Hamlet Conklin Hamlet Fort Chipewyan Hamlet Fort MacKay Hamlet Fort McMurray Hamlet December 18, 2020 Page 1 of 25 Gregoire Lake Estates Hamlet Janvier South Hamlet Saprae Creek Hamlet December 18, 2020 Page 2 of 25 MUNICIPALITY COMMUNITIES COMMUNITY STATUS MUNICIPAL DISTRICTS Acadia No. 34, M.D. of Acadia Valley Hamlet Athabasca County ATHABASCA Town BOYLE Village BONDISS Summer Village ISLAND LAKE SOUTH Summer Village ISLAND LAKE Summer Village MEWATHA BEACH Summer Village SOUTH BAPTISTE Summer Village SUNSET BEACH Summer Village WEST BAPTISTE Summer Village WHISPERING HILLS Summer Village Atmore Hamlet Breynat Hamlet Caslan Hamlet Colinton Hamlet -

St2 St9 St1 St3 St2

! SUPP2-Attachment 07 Page 1 of 8 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! .! ! ! ! ! ! SM O K Y L A K E C O U N T Y O F ! Redwater ! Busby Legal 9L960/9L961 57 ! 57! LAMONT 57 Elk Point 57 ! COUNTY ST . P A U L Proposed! Heathfield ! ! Lindbergh ! Lafond .! 56 STURGEON! ! COUNTY N O . 1 9 .! ! .! Alcomdale ! ! Andrew ! Riverview ! Converter Station ! . ! COUNTY ! .! . ! Whitford Mearns 942L/943L ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 56 ! 56 Bon Accord ! Sandy .! Willingdon ! 29 ! ! ! ! .! Wostok ST Beach ! 56 ! ! ! ! .!Star St. Michael ! ! Morinville ! ! ! Gibbons ! ! ! ! ! Brosseau ! ! ! Bruderheim ! . Sunrise ! ! .! .! ! ! Heinsburg ! ! Duvernay ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! 18 3 Beach .! Riviere Qui .! ! ! 4 2 Cardiff ! 7 6 5 55 L ! .! 55 9 8 ! ! 11 Barre 7 ! 12 55 .! 27 25 2423 22 ! 15 14 13 9 ! 21 55 19 17 16 ! Tulliby¯ Lake ! ! ! .! .! 9 ! ! ! Hairy Hill ! Carbondale !! Pine Sands / !! ! 44 ! ! L ! ! ! 2 Lamont Krakow ! Two Hills ST ! ! Namao 4 ! .Fort! ! ! .! 9 ! ! .! 37 ! ! . ! Josephburg ! Calahoo ST ! Musidora ! ! .! 54 ! ! ! 2 ! ST Saskatchewan! Chipman Morecambe Myrnam ! 54 54 Villeneuve ! 54 .! .! ! .! 45 ! .! ! ! ! ! ! ST ! ! I.D. Beauvallon Derwent ! ! ! ! ! ! ! STRATHCONA ! ! !! .! C O U N T Y O F ! 15 Hilliard ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! N O . 1 3 St. Albert! ! ST !! Spruce ! ! ! ! ! !! !! COUNTY ! TW O HI L L S 53 ! 45 Dewberry ! ! Mundare ST ! (ELK ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! . ! ! Clandonald ! ! N O . 2 1 53 ! Grove !53! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ISLAND) ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Ardrossan -

Published Local Histories

ALBERTA HISTORIES Published Local Histories assembled by the Friends of Geographical Names Society as part of a Local History Mapping Project (in 1995) May 1999 ALBERTA LOCAL HISTORIES Alphabetical Listing of Local Histories by Book Title 100 Years Between the Rivers: A History of Glenwood, includes: Acme, Ardlebank, Bancroft, Berkeley, Hartley & Standoff — May Archibald, Helen Bircham, Davis, Delft, Gobert, Greenacres, Kia Ora, Leavitt, and Brenda Ferris, e , published by: Lilydale, Lorne, Selkirk, Simcoe, Sterlingville, Glenwood Historical Society [1984] FGN#587, Acres and Empires: A History of the Municipal District of CPL-F, PAA-T Rocky View No. 44 — Tracey Read , published by: includes: Glenwood, Hartley, Hillspring, Lone Municipal District of Rocky View No. 44 [1989] Rock, Mountain View, Wood, FGN#394, CPL-T, PAA-T 49ers [The], Stories of the Early Settlers — Margaret V. includes: Airdrie, Balzac, Beiseker, Bottrell, Bragg Green , published by: Thomasville Community Club Creek, Chestermere Lake, Cochrane, Conrich, [1967] FGN#225, CPL-F, PAA-T Crossfield, Dalemead, Dalroy, Delacour, Glenbow, includes: Kinella, Kinnaird, Thomasville, Indus, Irricana, Kathyrn, Keoma, Langdon, Madden, 50 Golden Years— Bonnyville, Alta — Bonnyville Mitford, Sampsontown, Shepard, Tribune , published by: Bonnyville Tribune [1957] Across the Smoky — Winnie Moore & Fran Moore, ed. , FGN#102, CPL-F, PAA-T published by: Debolt & District Pioneer Museum includes: Bonnyville, Moose Lake, Onion Lake, Society [1978] FGN#10, CPL-T, PAA-T 60 Years: Hilda’s Heritage, -

2017 Municipal Codes

2017 Municipal Codes Updated December 22, 2017 Municipal Services Branch 17th Floor Commerce Place 10155 - 102 Street Edmonton, Alberta T5J 4L4 Phone: 780-427-2225 Fax: 780-420-1016 E-mail: [email protected] 2017 MUNICIPAL CHANGES STATUS CHANGES: 0315 - The Village of Thorsby became the Town of Thorsby (effective January 1, 2017). NAME CHANGES: 0315- The Town of Thorsby (effective January 1, 2017) from Village of Thorsby. AMALGAMATED: FORMATIONS: DISSOLVED: 0038 –The Village of Botha dissolved and became part of the County of Stettler (effective September 1, 2017). 0352 –The Village of Willingdon dissolved and became part of the County of Two Hills (effective September 1, 2017). CODE NUMBERS RESERVED: 4737 Capital Region Board 0522 Metis Settlements General Council 0524 R.M. of Brittania (Sask.) 0462 Townsite of Redwood Meadows 5284 Calgary Regional Partnership STATUS CODES: 01 Cities (18)* 15 Hamlet & Urban Services Areas (396) 09 Specialized Municipalities (5) 20 Services Commissions (71) 06 Municipal Districts (64) 25 First Nations (52) 02 Towns (108) 26 Indian Reserves (138) 03 Villages (87) 50 Local Government Associations (22) 04 Summer Villages (51) 60 Emergency Districts (12) 07 Improvement Districts (8) 98 Reserved Codes (5) 08 Special Areas (3) 11 Metis Settlements (8) * (Includes Lloydminster) December 22, 2017 Page 1 of 13 CITIES CODE CITIES CODE NO. NO. Airdrie 0003 Brooks 0043 Calgary 0046 Camrose 0048 Chestermere 0356 Cold Lake 0525 Edmonton 0098 Fort Saskatchewan 0117 Grande Prairie 0132 Lacombe 0194 Leduc 0200 Lethbridge 0203 Lloydminster* 0206 Medicine Hat 0217 Red Deer 0262 Spruce Grove 0291 St. Albert 0292 Wetaskiwin 0347 *Alberta only SPECIALIZED MUNICIPALITY CODE SPECIALIZED MUNICIPALITY CODE NO. -

Communities Within Specialized and Rural Municipalities (May 2019)

Communities Within Specialized and Rural Municipalities Updated May 24, 2019 Municipal Services Branch 17th Floor Commerce Place 10155 - 102 Street Edmonton, Alberta T5J 4L4 Phone: 780-427-2225 Fax: 780-420-1016 E-mail: [email protected] COMMUNITIES WITHIN SPECIALIZED AND RURAL MUNICIPAL BOUNDARIES COMMUNITY STATUS MUNICIPALITY Abee Hamlet Thorhild County Acadia Valley Hamlet Municipal District of Acadia No. 34 ACME Village Kneehill County Aetna Hamlet Cardston County ALBERTA BEACH Village Lac Ste. Anne County Alcomdale Hamlet Sturgeon County Alder Flats Hamlet County of Wetaskiwin No. 10 Aldersyde Hamlet Foothills County Alhambra Hamlet Clearwater County ALIX Village Lacombe County ALLIANCE Village Flagstaff County Altario Hamlet Special Areas Board AMISK Village Municipal District of Provost No. 52 ANDREW Village Lamont County Antler Lake Hamlet Strathcona County Anzac Hamlet Regional Municipality of Wood Buffalo Ardley Hamlet Red Deer County Ardmore Hamlet Municipal District of Bonnyville No. 87 Ardrossan Hamlet Strathcona County ARGENTIA BEACH Summer Village County of Wetaskiwin No. 10 Armena Hamlet Camrose County ARROWWOOD Village Vulcan County Ashmont Hamlet County of St. Paul No. 19 ATHABASCA Town Athabasca County Atmore Hamlet Athabasca County Balzac Hamlet Rocky View County BANFF Town Improvement District No. 09 (Banff) BARNWELL Village Municipal District of Taber BARONS Village Lethbridge County BARRHEAD Town County of Barrhead No. 11 BASHAW Town Camrose County BASSANO Town County of Newell BAWLF Village Camrose County Beauvallon Hamlet County of Two Hills No. 21 Beaver Crossing Hamlet Municipal District of Bonnyville No. 87 Beaver Lake Hamlet Lac La Biche County Beaver Mines Hamlet Municipal District of Pincher Creek No. 9 Beaverdam Hamlet Municipal District of Bonnyville No. -

Regional Waste Management Authority Contact List 2016

Regional Waste Management Authority Contact List 2016 July 29, 2016 Table of Contents NORTHERN ALBERTA....................................................................................................................................................... 5 ATHABASCA REGIONAL WASTE MANAGEMENT SERVICES COMMISSION ......................... 5 BEAVER RIVER REGIONAL WASTE MANAGEMENT COMMISSION ........................................ 5 CENTRAL PEACE REGIONAL WASTE MANAGEMENT COMMISSION ..................................... 6 PEACE REGIONAL WASTE MANAGEMENT COMPANY ................................................................ 6 EVERGREEN REGIONAL WASTE MANAGEMENT SERVICES COMMISSION ......................... 7 GREENVIEW REGIONAL WASTE MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY ............................................... 8 HIGH PRAIRIE & DISTRICT REGIONAL SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY ......... 9 ST. MICHAEL REGIONAL SOLID WASTE COMMISSION ............................................................. 9 LESSER SLAVE LAKE REGIONAL WASTE MANAGEMENT SERVICES COMMISSION ....... 10 LONG LAKE REGIONAL WASTE MANAGEMENT SERVICES COMMISSION ......................... 10 MACKENZIE REGIONAL WASTE MANAGEMENT COMMISSION ............................................ 11 NORTH PEACE REGIONAL LANDFILL (formerly Fairview) .......................................................... 11 ROSERIDGE WASTE MANAGEMENT SERVICES COMMISSION .............................................. 12 SMOKY RIVER REGIONAL WASTE MANAGEMENT COMMISSION ........................................ 12 WEST GRANDE -

2019 Alberta Highway Historical ESAL Report (PDF Version)

ALBERTA HIGHWAY HISTORICAL ESAL REPORT 2019 Alberta Transportation Produced: 10-Mar-2020 By CornerStone Solutions Inc. Length ESAL / Day / Dir Hwy CS TCS Muni From To in Km WAADT 2019 2018 2017 2016 2015 2014 2013 2012 2011 2010 2009 2008 2007 2006 1 2 4 Bigh BANFF PARK GATE W OF 1A NW OF CANMORE WJ 3.777 23570 2220 2140 1760 1710 1600 1470 1370 1610 1550 1550 1530 1370 1400 1370 1 2 8 Bigh E OF 1A NW OF CANMORE WJ W OF 1A S OF CANMORE EJ 4.741 20610 2050 1980 1730 1690 1590 1620 1530 1570 1500 1250 1230 1140 1160 1300 1 2 12 KanC E OF 1A S OF CANMORE EJ W OF 1X S OF SEEBE 23.165 22470 2050 1980 1680 1660 1570 1510 1420 1810 1730 1680 1660 1700 1710 1690 1 2 16 KanC E OF 1X S OF SEEBE KANANASKIS RIVER 0.896 22790 2750 2650 2360 2350 2240 2080 1970 2050 1960 1960 1920 2110 2110 2020 1 2 BANFF PARK GATE KANANASKIS RIVER 32.579 22336 2090 2010 1720 1690 1590 1530 1440 1750 1670 1600 1580 1590 1600 1610 1 4 4 Bigh KANANASKIS RIVER W OF 40 AT SEEBE 3.228 22790 2140 2070 1820 1810 1720 1600 1510 1630 1560 1560 1530 1520 1530 1460 1 4 8 Bigh E OF 40 AT SEEBE E BDY STONY INDIAN RESERVE 22.296 24210 2470 2380 2310 2310 2230 2070 1960 1980 1650 1650 1580 1270 1230 1170 1 4 KANANASKIS RIVER E BDY STONY INDIAN RESERVE 25.524 24030 2430 2340 2240 2240 2160 2010 1900 1940 1640 1630 1570 1300 1270 1210 1 6 4 Rkyv E BDY STONY INDIAN RESERVE W OF JCT 68 3.166 23390 1990 1920 2040 2040 1950 1810 1710 2140 2040 2030 1970 2250 2250 2150 1 6 8 Rkyv E OF JCT 68 W OF 22 S OF COCHRANE 17.235 23890 2410 2330 2520 2530 2640 2490 2360 2410 2010 2000 1960 1880 1800 1690 1 6 E BDY STONY INDIAN RESERVE W OF 22 S OF COCHRANE 20.401 23812 2360 2280 2450 2450 2540 2390 2260 2360 2010 2000 1950 1930 1880 1760 1 8 4 Rkyv E OF 22 S OF COCHRANE W OF 563 W OF CALGARY 11.441 30670 1960 1630 1610 1570 1550 1380 1300 1160 1110 1100 1060 1020 1010 940 1 8 8 Rkyv E OF 563 W OF CALGARY CALGARY W.C.L. -

Le Grand Sentier D'alberta

The Great Trail in Alberta Le Grand Sentier d’Alberta This marks the connection of Alberta’s section of The Great Trail of Canada in honour of Canada’s 150th anniversary Ceci marque le raccordement du Grand Sentier à travers d’Alberta pour le 150e anniversaire de la Confédération of Confederation in 2017. canadienne en 2017. À partir d’où vous êtes, vous pouvez entreprendre l’un des voyages les plus beaux et les plus diversifiés du monde. From where you are standing, you can embark upon one of the most magnificent and diverse journeys in the world. Que vous vous dirigiez vers l’est, l’ouest, le nord ou le sud, Le Grand Sentier du Canada — créé par le sentier Whether heading east, west, north or south, The Great Trail—created by Trans Canada Trail (TCT) and its partners— Transcanadien (STC) et ses partenaires — vous offre ses multiples beautés naturelles ainsi que la riche histoire et offers all the natural beauty, rich history and enduring spirit of our land and its peoples. l’esprit qui perdure de notre pays et des gens qui l’habitent. Launched in 1992, just after Canada’s 125th anniversary of Confederation The Great Trail was conceived by a group of Lancé en 1992, juste après le 125e anniversaire de la Confédération du Canada, Le Grand Sentier a été conçu, par un visionary and patriotic individuals as a means to connect Canadians from coast to coast to coast. groupe de visionnaires et de patriotes, comme le moyen de relier les Canadiens d’un océan aux deux autres. -

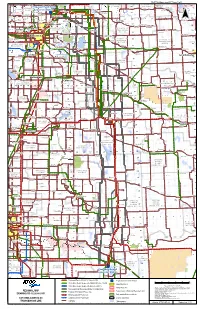

Legend - AUPE Area Councils Whiskey Gap Del Bonita Coutts

Indian Cabins Steen River Peace Point Meander River 35 Carlson Landing Sweet Grass Landing Habay Fort Chipewyan 58 Quatre Fourches High Level Rocky Lane Rainbow Lake Fox Lake Embarras Portage #1 North Vermilion Settlemen Little Red River Jackfish Fort Vermilion Vermilion Chutes Fitzgerald Embarras Paddle Prairie Hay Camp Carcajou Bitumount 35 Garden Creek Little Fishery Fort Mackay Fifth Meridian Hotchkiss Mildred Lake Notikewin Chipewyan Lake Manning North Star Chipewyan Lake Deadwood Fort McMurray Peerless Lake #16 Clear Prairie Dixonville Loon Lake Red Earth Creek Trout Lake #2 Anzac Royce Hines Creek Peace River Cherry Point Grimshaw Gage 2 58 Brownvale Harmon Valley Highland Park 49 Reno Blueberry Mountain Springburn Atikameg Wabasca-desmarais Bonanza Fairview Jean Cote Gordondale Gift Lake Bay Tree #3 Tangent Rycroft Wanham Eaglesham Girouxville Spirit River Mclennan Prestville Watino Donnelly Silverwood Conklin Kathleen Woking Guy Kenzie Demmitt Valhalla Centre Webster 2A Triangle High Prairie #4 63 Canyon Creek 2 La Glace Sexsmith Enilda Joussard Lymburn Hythe 2 Faust Albright Clairmont 49 Slave Lake #7 Calling Lake Beaverlodge 43 Saulteaux Spurfield Wandering River Bezanson Debolt Wembley Crooked Creek Sunset House 2 Smith Breynat Hondo Amesbury Elmworth Grande Calais Ranch 33 Prairie Valleyview #5 Chisholm 2 #10 #11 Grassland Plamondon 43 Athabasca Atmore 55 #6 Little Smoky Lac La Biche Swan Hills Flatbush Hylo #12 Colinton Boyle Fawcett Meanook Cold Rich Lake Regional Ofces Jarvie Perryvale 33 2 36 Lake Fox Creek 32 Grand Centre Rochester 63 Fort Assiniboine Dapp Peace River Two Creeks Tawatinaw St. Lina Ardmore #9 Pibroch Nestow Abee Mallaig Glendon Windfall Tiger Lily Thorhild Whitecourt #8 Clyde Spedden Grande Prairie Westlock Waskatenau Bellis Vilna Bonnyville #13 Barrhead Ashmont St. -

2017 ABVMA Member Directory

2017 MEMBER DIRECTORY ELLNESS FOR THE VETERINARY TEAM W body mind spirit heart The responsibilities of caring for patients, clients and our families can sometimes lead to burnout, compassion fatigue, and suicidal thoughts. IF YOU ARE FEELING SAD OR DEPRESSED PLEASE REACH OUT ABVMA Member Wellness Program (for Veterinarians and AHTs): 780-435-5908 or 1-888-399-9876 For all members of the Veterinary Team (24 hour): HealthLink: 1-866-408-5465 Urgent Services: 780-342-7777 Crisis/Distress Line: Edmonton and area: 780-342-7600 Calgary and area: 403-266-1605 PROFESSIONALS HELPING PROFESSIONALS TABLE OF CONTENTS ABVMA Leadership The Alberta Veterinary Medical Association ....................................................................................................................................4 Staff 2017 ..........................................................................................................................................................................................4 Privacy Statement .............................................................................................................................................................................4 Canadian Veterinary Oath ................................................................................................................................................................5 2017 ABVMA Council.....................................................................................................................................................................5