Goldberg Variations” and Ian Mcewan’S Saturday

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sounding Nostalgia in Post-World War I Paris

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2019 Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris Tristan Paré-Morin University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Recommended Citation Paré-Morin, Tristan, "Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris" (2019). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 3399. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3399 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3399 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris Abstract In the years that immediately followed the Armistice of November 11, 1918, Paris was at a turning point in its history: the aftermath of the Great War overlapped with the early stages of what is commonly perceived as a decade of rejuvenation. This transitional period was marked by tension between the preservation (and reconstruction) of a certain prewar heritage and the negation of that heritage through a series of social and cultural innovations. In this dissertation, I examine the intricate role that nostalgia played across various conflicting experiences of sound and music in the cultural institutions and popular media of the city of Paris during that transition to peace, around 1919-1920. I show how artists understood nostalgia as an affective concept and how they employed it as a creative resource that served multiple personal, social, cultural, and national functions. Rather than using the term “nostalgia” as a mere diagnosis of temporal longing, I revert to the capricious definitions of the early twentieth century in order to propose a notion of nostalgia as a set of interconnected forms of longing. -

Collection 1" De Christophe

Collection "Collection 1" de christophe Artiste Titre Format Ref Pays de pressage 10cc The Original Soundtrack LP mip19305 Canada 10cc How Dare You! LP mip 19316 Canada 10cc Deceptive Bends LP 6310502 Pays-Bas 38 Special Tour De Force LP AMlh64971 Pays-Bas 38 Special Strength Numbers LP Inconnu 38 Special Special Forces LP amlh64888 Inconnu Ac Dc For Those About To Rock Maxi 45T atl k 20 276 Allemagne Ac/dc Tnt LP aplpa 016 Australie Ac/dc Rock Or Bust LP Inconnu Ac/dc Powerage LP atl 50 483 Allemagne Ac/dc Let There Be Rock LP atl 50 366 France Ac/dc If You Want Blood You've Got I...LP atl 50 532 Allemagne Ac/dc Highway To Hell LP 50 628 France Ac/dc Highway To Hell LP atl 50 628 Allemagne Ac/dc High Voltage LP atl 50 237 Allemagne Ac/dc For Those About To Rock We Sal...LP atl k 50 851 Allemagne Ac/dc Fly On The Wall LP Inconnu Ac/dc Flick Of The Switch LP Inconnu Ac/dc Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap LP 50323 France Ac/dc Black Ice LP 88697 38377 1 EU Ac/dc Back In Black LP 5107651 EU Ac/dc ...and There Was Guitar LP Inconnu Ac/dc '74 Jailbreak LP 80178 1 Y Etats Unis Amerique Accept Staying A Life LP nl 74720 Allemagne Ace Frehley Frehley's Comet LP 81749 Etats Unis Amerique Adderlay Cannonball Nancy Wilson/cannonball Adderl...LP Inconnu Adderlay Cannonball At San Francisco LP Inconnu Adderly Julian Cannonball 1955 LP Inconnu Aerosmith Toys In The Attic LP cbs 80773 Pays-Bas Aerosmith Rocks LP pc 34165 Etats Unis Amerique Aerosmith Music From Another Dimension 2LP Inconnu Aerosmith Live! Bootleg 2LP Inconnu Aerosmith Get Your Wings LP 466732 1 Pays-Bas Aerosmith Draw The Line LP 82145 Pays-Bas Aerosmith Aerosmith LP 32203 Pays-Bas Airbourne Runnin' Wild LP rrcar7963 1 Allemagne Al Jarreau Al Jarreau - 1965 - Disc'az - .. -

Le Monde Des Guitares Taylor/Numero 75 Printemps 2013

La face cachée de l’ébène Éditions limitées de printemps, série 600 Série 400 granadillo Série PS en palissandre du Honduras Grand Orchestra tout koa K28e First Edition Temps forts du NAMM Suivi des progrès au Cameroun Galerie d’art sur mesure 2 www.taylorguitars.com 3 fiques, et je repense souvent à ce jeune un bijou entre les mains ! J’ai joué des avec ma [autre marque acoustique], enfant qui a reçu la Baby de son pro- guitares d’autres marques pendant des mais désormais je n’utiliserai plus Courrier fesseur. J’espère qu’il a tiré profit de ce années, et cette Taylor m’a permis de que cette Taylor ! Le diapason court, Numéro 75 cadeau extraordinaire, et qu’il a fait de multiplier ma confiance envers mon la fantastique combinaison de bois la guitare sa passion d’une vie. Mandy propre jeu. J’essayais de décrire son [NDLR : acacia à bois noir/cèdre] et Printemps 2013 Retrouvez-nous sur Facebook et YouTube. Suivez-nous sur Twitter : @taylorguitars je dois dire que j’adore à la fois la taille joue désormais sur une 314ce, et ma son à un de mes amis, et tout ce que le prix spécial (elle était légèrement de la Mini et le fait que cette taille ne préférée est une GS érable custom ; j’ai trouvé à lui dire, c’est qu’elle me endommagée) m’ont fait revenir dans la sacrifie pas le son, loin de là. Après mais nous nous souviendrons toujours donnait l’impression qu’il y avait toute famille Taylor. -

Borrowed Forms the Music and Ethics of Transnational Fiction

Borrowed Forms The Music and Ethics of Transnational Fiction Lachman, Borrowed Forms.indd 1 06/05/2014 09:30:15 Lachman, Borrowed Forms.indd 2 06/05/2014 09:30:15 Borrowed Forms The Music and Ethics of Transnational Fiction Kathryn Lachman LIVERPOOL UNIVERSITY PRESS Lachman, Borrowed Forms.indd 3 06/05/2014 09:30:15 Borrowed Forms First published 2014 by Liverpool University Press 4 Cambridge Street Liverpool L69 7ZU Copyright © 2014 Kathryn Lachman The right of Kathryn Lachman to be identified as the author of this book has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication data A British Library CIP record is available ISBN 978-1-78138-030-7 Typeset by Carnegie Book Production, Lancaster Printed and bound by Booksfactory.co.uk Lachman, Borrowed Forms.indd 4 06/05/2014 09:30:15 Contents Contents Acknowledgements vii Introduction 1 1 From Mikhail Bakhtin to Maryse Condé: the Problems of Literary Polyphony 29 2 Edward Said and Assia Djebar: Counterpoint and the Practice of Comparative Literature 59 3 Glenn Gould and the Birth of the Author: Variation and Performance in Nancy Huston’s Les variations Goldberg 89 4 Opera and the Limits of Representation in J. M. Coetzee’s Disgrace 113 Conclusion 137 Notes 147 Works Cited 175 Index 195 Lachman, Borrowed Forms.indd 5 06/05/2014 09:30:15 Lachman, Borrowed Forms.indd 6 06/05/2014 09:30:15 Acknowledgements Acknowledgements I completed this book at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, where I have benefited greatly from the support and generosity of my chairs: Julie Hayes, Bill Moebius, Patrick Mensah, David Lenson, and Jim Hicks. -

Vinyls-Collection.Com Page 1/38 - Total : 1482 Vinyls Au 02/10/2021 Collection "Collection 1 Vinyl" De Jj26

Collection "Collection 1 vinyl" de jj26 Artiste Titre Format Ref Pays de pressage 999 Lust Power And Money LP 130093 France Abrial (patrick Abrial) Vidéo LP AVC 130025 France Abrial Patrick (patrick Abrial... Chanson Pour Marie LP S63625 France Abrial Stratageme Group Same LP Inconnu Ac/dc Tnt LP Inconnu Ac/dc Powerage LP Inconnu Ac/dc Let There Be Rock LP Inconnu Ac/dc If You Want Blood You've Got I...LP Inconnu Ac/dc High Voltage LP Inconnu Ac/dc High Voltage LP Australie Ac/dc Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap LP Inconnu Ac/dc Back In Black LP Inconnu Accept Metal Heart LP Inconnu Accept I'm A Rebel LP Inconnu Ace Five A Side LP ANCL 2001 Royaume-Uni Adriano Celentano Tecadisk By Adriano Celentano LP Inconnu Aerosmith Toys In The Attic LP Inconnu Aerosmith Rocks LP Inconnu Aerosmith Live! Bootleg LP Inconnu Aerosmith Get Your Wings LP Inconnu Aerosmith Draw The Line LP Inconnu Aerosmith Aerosmith's Greatest Hits LP Inconnu Aerosmith Aerosmith LP Inconnu Airbourne Black Dog Barking LP Inconnu Alabama The Closer You Get... LP Inconnu Alan White Ramshackled LP Inconnu Alice Cooper Zipper Catches Skin LP Inconnu Alice Cooper Welcome To My Nightmare LP Inconnu Alice Cooper School's Out LP Inconnu Alice Cooper Love It To Death LP Inconnu Alice Cooper Killer LP Inconnu Alice Cooper Easy Action LP Inconnu Alice Cooper Billion Dollar Babies LP Inconnu Alice Cooper Alice Cooper's Greatest Hits LP Inconnu Alien Cosmic Fantasy - 6 Song Ep LP Inconnu Alkatraz Doing A Moonlight By Alkatraz LP Inconnu Alphaville Afternoons In Utopia K7 Inconnu Alvin Lee -

Generating Geographies and Genealogies: Jewish Women

GENERATING GEOGRAPHIES AND GENEALOGIES: JEWISH WOMEN WRITING THE TWENTIETH CENTURY IN FRENCH by NATALIE RACHEL KAFTAN BRENNER A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of Romance Languages and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2019 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Natalie Rachel Kaftan Brenner Title: Generating Geographies and Genealogies: Jewish Women Writing the Twentieth Century in French This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the Department of Romance Languages by: Evlyn Gould Chairperson and Advisor Karen McPherson Core Member Gina Herrmann Core Member Judith Raiskin Institutional Representative and Janet Woodruff-Borden Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2019 ii © 2019 Natalie Rachel Kaftan Brenner iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Natalie Rachel Kaftan Brenner Doctor of Philosophy Department of Romance Languages June 2019 Title: Generating Geographies and Genealogies: Jewish Women Writing the Twentieth Century in French This dissertation offers an alternative account of Jewish history and experience from within the post-Holocaust and postcolonial Francophone world through the study of six autobiographically-inclined texts written by three generations of Francophone Jewish women of diverse geographical origins. While France was the first European nation-state to grant citizenship to Jews in 1791 and the French Republic has since branded itself as a beacon of tolerance, this tolerance has been contingent upon a strict politics of assimilation and has been challenged by French colonization and participation in the Holocaust. -

Faouda Wa Ruina: a History of Moroccan Punk Rock and Heavy Metal Brian Kenneth Trott University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations May 2018 Faouda Wa Ruina: A History of Moroccan Punk Rock and Heavy Metal Brian Kenneth Trott University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Islamic World and Near East History Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Trott, Brian Kenneth, "Faouda Wa Ruina: A History of Moroccan Punk Rock and Heavy Metal" (2018). Theses and Dissertations. 1934. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/1934 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FAOUDA WA RUINA: A HISTORY OF MOROCCAN PUNK ROCK AND HEAVY METAL by Brian Trott A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of a Degree of Master of Arts In History at The University of Wisconsin - Milwaukee May 2018 ABSTRACT FAOUDA WA RUINA: A HISTORY OF MOROCCAN PUNK ROCK AND HEAVY METAL by Brian Trott The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2018 Under the Supervision of Professor Gregory Carter While the punk rock and heavy metal subcultures have spread through much of the world since the 1980s, a heavy metal scene did not take shape in Morocco until the mid-1990s. There had yet to be a punk rock band there until the mid-2000s. In the following paper, I detail the rise of heavy metal in Morocco. Beginning with the early metal scene, I trace through critical moments in its growth, building up to the origins of the Moroccan punk scene and the state of those subcultures in recent years. -

BT Manuel.Pdf

BLUZJAM REALISÉ PAR BLUZ TRACK BLUZ PAR REALISÉ BLUZ TRACK organise régulièrement des Jams Sessions, s’il est plutôt facile de venir « faire le bœuf » pour un musicien professionnel ou les habitués de la scène blues, cela peut être déroutant pour un débutant ou un musicien venant d’un autre style. Ce livret a pour but d’aider les débutants à accéder à notre scène ouverte avec une explication rapide des codes, de la grille et de la gamme Blues. Nous avons aussi inclus les paroles et les grilles de quelques standards que l’on retrouve fréquemment dans nos « bœufs » afin que vous puissiez être plus à l’aise pour venir partager un bon moment avec nous ainsi qu’une liste de classiques que tout amateur de blues a déjà entendus au moins une fois. L’Équipe Bluz Track Bluz Track Manuel de la Jam 2 SOMMAIRE La Grille Blues 4 Exemples de Grilles 4 La Gamme Blues 7 Généralités 8 Guitare 9 Piano 10 Harmonica Diatonique 11 Saxophone Ténor ou Instrument en Sib 12 Le Blues & le Ternaire 13 Shuffle – définition et notation 13 La Bluz Jam 15 Standards 16 Sources 31 Conception & réalisation 31 Bluz Track Manuel de la Jam 3 La Grille Blues La grille blues standard tourne autour de trois accords : les accords de Ier, IVème et Vième degrés. Que signifient ces degrés ? Pour ceux qui n'ont pas cette connaissance théorique, voici une courte explication : Les degrés permettent de positionner une note ou un accord par rapport à n'importe quelle gamme afin de garder une cohérence. -

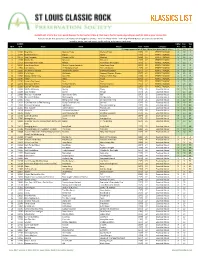

KLASSICS LIST Criteria

KLASSICS LIST criteria: 8 or more points (two per fan list, two for U-Man A-Z list, two to five for Top 95, depending on quartile); 1984 or prior release date Sources: ten fan lists (online and otherwise; see last page for details) + 2011-12 U-Man A-Z list + 2014 Top 95 KSHE Klassics (as voted on by listeners) sorted by points, Fan Lists count, Top 95 ranking, artist name, track name SLCRPS UMan Fan Top ID # ID # Track Artist Album Year Points Category A-Z Lists 95 35 songs appeared on all lists, these have green count info >> X 10 n 1 12404 Blue Mist Mama's Pride Mama's Pride 1975 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 1 2 12299 Dead And Gone Gypsy Gypsy 1970 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 2 3 11672 Two Hangmen Mason Proffit Wanted 1969 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 5 4 11578 Movin' On Missouri Missouri 1977 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 6 5 11717 Remember the Future Nektar Remember the Future 1973 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 7 6 10024 Lake Shore Drive Aliotta Haynes Jeremiah Lake Shore Drive 1971 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 9 7 11654 Last Illusion J.F. Murphy & Salt The Last Illusion 1973 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 12 8 13195 The Martian Boogie Brownsville Station Brownsville Station 1977 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 13 9 13202 Fly At Night Chilliwack Dreams, Dreams, Dreams 1977 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 14 10 11696 Mama Let Him Play Doucette Mama Let Him Play 1978 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 15 11 11547 Tower Angel Angel 1975 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 19 12 11730 From A Dry Camel Dust Dust 1971 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 20 13 12131 Rosewood Bitters Michael Stanley Michael Stanley 1972 27 PERFECT -

KKUP-2019-Gifts-Ver-14-06-13-19

Page Artist Title / Description Pledge In Psych We Trust! (Band & Artist Spotlight) 6 The Byrds “Original Album Classics” 5-CD Box Set $80.00 7 The Byrds “Sweethearts of The Radio” (&) “Untitled / Unissued” Deluxe Edition 2-CD Sets with One Tote Bag or $100.0 Sports Cap 8 The Flying Burrito Bros “The Gilded Palace of Sin”, “Burrito Deluxe” (&) “Authorized Bootleg: Fillmore East, N.Y., N.Y. Late $100.00 Show, Nov. 7 1970” Limited Edition Sets with One Tote Bag or Sports Cap 9 Free “Five Album Classics” 5-CD Box Set $80.00 10 The Guess Who “Five Original Album Classics” 5-CD Box Set $80.00 11 The Hollies “The Clarke Hicks & Nash Years” 6-CD Imported Deluxe Box Set with One Tote Bag or Sports Cap $100.00 12 Jethro Tull “This Was” Super Deluxe Edition 3-CD / 1-DVD Audio Box Set with One Tote Bag (&) One Sports Cap $100.00 13 The Lovin’ Spoonful “Original Album Classics” 5-CD Box Set $80.00 14 Mountain “Original Album Classics” 5-CD Box Set $80.00 15 Sly & The Family Stone “Five Original Album Classics” 5-CD Box Set $80.00 16 Tommy James & The Shondells “Original Album Classics” 5-CD Box Set $80.00 17 Traffic “Five Classic Albums” 5-CD Box Set $80.00 Progaholic Deluvian-Delights (Special Progressive Rock Anthologies) 19 Deep Purple “In Rock” & “Made in Japan” Special 2-CD Bundle $80.00 20 Emerson, Lake & Palmer “Lucky Man (The Masters Collection)” 2-CD Anthology $80.00 21 Genesis & Pink Floyd Genesis’ “Selling England by The Pound” (&) Pink Floyd’s “Meddle” Special 2-CD Bundle $80.00 22 The Moody Blues “Five Classic Albums” Imported 5-CD Box -

Le Blues Style De Musique

Le Blues Style de musique PDF générés en utilisant l’atelier en source ouvert « mwlib ». Voir http://code.pediapress.com/ pour plus d’informations. PDF generated at: Wed, 20 Mar 2013 19:02:25 UTC Contenus Articles Origine et Style 1 Origines du blues 1 Musique afro-américaine 4 Blues 15 Negro spiritual 27 Notes et Instruments 32 Note bleue 32 Harmonica 34 Piano 40 Guitare 59 Grands musiciens 76 Ma Rainey 76 Muddy Waters 77 B. B. King 82 Stevie Ray Vaughan 87 Références Sources et contributeurs de l’article 92 Source des images, licences et contributeurs 94 Licence des articles Licence 96 1 Origine et Style Origines du blues Cet article est une ébauche concernant le blues. Vous pouvez partager vos connaissances en l’améliorant (comment ?) selon les recommandations des projets correspondants. On sait peu de choses à propos des origines exactes de la musique que l'on désigne aujourd'hui comme le blues. Il est difficile de dater précisément les origines du blues, en grande partie parce que ce style de musique a évolué sur une longue période et existait avant même que l'on utilise le terme "blues". Une référence importante à ce qui se rapproche étroitement du blues date de 1901, lorsqu'un archéologue du Mississippi a décrit les chansons des ouvriers et esclaves noirs dont les chants reposaient sur des thèmes et des éléments techniques caractéristiques du blues. Blues et africain spiritual Il y a de nombreuses origines probables du blues dont les racines sont multiples et plongent au cœur de l'histoire du peuplement de l'Amérique du Nord (Americana, Fayard). -

Dossier Hard Rock

Hard rock : le rêve sur amplifié J’aime imaginer la réaction des premiers spectateurs de Jimi Hendix lorsque celui-ci foula pour la première fois une scène anglaise en première partie d’Eric Clapton. Certes Clapton avait lui-même initié la tendance à la sur amplification avec le trio cream. Mais, peut enclin aux grandes démonstrations de forces, celui que l’on appelait déjà dieux faisait partie d’un groupe ou chaque membre avait la même importance. Cette égalité, Hendrix la dynamitait grâce à son génie et son sens du spectacle, et les musiciens de l’expérience restait gentiment au second plan. Avec son attitude, la puissance de ses riffs et son charisme sur scène, Hendrix inventait le culte du guitar hero. D’autres éléments viendront initier le son et l’esthétique du hard rock. Parmi les plus fameux on peut citer le rock psychélique agressif de blue cheer et autres vanilla fudge ou le fameux born to be wild de steppenwolf. Mais tous ces élément ne seront réunit qu’a partir de la sortie du premier led zeppelin. Ce premier album est le premier à proposer du blues surpuissant, avec pour seul temps mort des ballades mélodique comme le hard rock saura en produire par la suite. A partir de cet acte fondateur paru en 1969, les groupes amoureux de gros son allaient se multiplier pour élargir le spectre musical du hard rock. Deep Purple : un rendez vous manqué avec l’histoire Loins d’étre un descendant de led zeppelin, Deep purple se forme en 1968. Mais ce groupe n’aura pas une vision artisique aussi claire et lui faudra sortir 3 albums avant de trouver sa voie.