Honeypots: Not for Winnie the Pooh But

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Internet and Drug Markets

INSIGHTS EN ISSN THE INTERNET AND DRUG MARKETS 2314-9264 The internet and drug markets 21 The internet and drug markets EMCDDA project group Jane Mounteney, Alessandra Bo and Alberto Oteo 21 Legal notice This publication of the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) is protected by copyright. The EMCDDA accepts no responsibility or liability for any consequences arising from the use of the data contained in this document. The contents of this publication do not necessarily reflect the official opinions of the EMCDDA’s partners, any EU Member State or any agency or institution of the European Union. Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) The information given is free, as are most calls (though some operators, phone boxes or hotels may charge you). More information on the European Union is available on the internet (http://europa.eu). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2016 ISBN: 978-92-9168-841-8 doi:10.2810/324608 © European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, 2016 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. This publication should be referenced as: European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (2016), The internet and drug markets, EMCDDA Insights 21, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg. References to chapters in this publication should include, where relevant, references to the authors of each chapter, together with a reference to the wider publication. For example: Mounteney, J., Oteo, A. and Griffiths, P. -

Sex, Drugs, and Bitcoin: How Much Illegal Activity Is Financed Through Cryptocurrencies? *

Sex, drugs, and bitcoin: How much illegal activity is financed through cryptocurrencies? * Sean Foley a, Jonathan R. Karlsen b, Tālis J. Putniņš b, c a University of Sydney b University of Technology Sydney c Stockholm School of Economics in Riga January, 2018 Abstract Cryptocurrencies are among the largest unregulated markets in the world. We find that approximately one-quarter of bitcoin users and one-half of bitcoin transactions are associated with illegal activity. Around $72 billion of illegal activity per year involves bitcoin, which is close to the scale of the US and European markets for illegal drugs. The illegal share of bitcoin activity declines with mainstream interest in bitcoin and with the emergence of more opaque cryptocurrencies. The techniques developed in this paper have applications in cryptocurrency surveillance. Our findings suggest that cryptocurrencies are transforming the way black markets operate by enabling “black e-commerce”. JEL classification: G18, O31, O32, O33 Keywords: blockchain, bitcoin, detection controlled estimation, illegal trade * We thank an anonymous referee, Andrew Karolyi, Maureen O’Hara, Paolo Tasca, Michael Weber, as well as the conference/seminar participants of the RFS FinTech Workshop of Registered Reports, the Behavioral Finance and Capital Markets Conference, the UBS Equity Markets Conference, and the University of Technology Sydney. Jonathan Karlsen acknowledges financial support from the Capital Markets Co-operative Research Centre. Tālis Putniņš acknowledges financial support from the Australian Research Council (ARC) under grant number DE150101889. The Online Appendix that accompanies this paper can be found at goo.gl/GvsERL Send correspondence to Tālis Putniņš, UTS Business School, University of Technology Sydney, PO Box 123 Broadway, NSW 2007, Australia; telephone: +61 2 95143088. -

Deepweb and Cybercrime It’S Not All About TOR

A Trend Micro Research Paper Deepweb and Cybercrime It’s Not All About TOR Vincenzo Ciancaglini, Marco Balduzzi, Max Goncharov, and Robert McArdle Forward-Looking Threat Research Team Trend Micro | Deepweb and Cybercrime Contents Abstract ..................................................................................................................................................3 Introduction ...........................................................................................................................................3 Overview of Existing Deepweb Networks ......................................................................................5 TOR ............................................................................................................................................5 I2P ...............................................................................................................................................6 Freenet .......................................................................................................................................7 Alternative Domain Roots ......................................................................................................7 Cybercrime in the TOR Network .......................................................................................................9 TOR Marketplace Overview ..................................................................................................9 TOR Private Offerings ..........................................................................................................14 -

Economics of Illicit Behaviors: Exchange in the Internet Wild West

ECONOMICS OF ILLICIT BEHAVIORS: EXCHANGE IN THE INTERNET WILD WEST by Julia R. Norgaard A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of George Mason University in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Economics Committee: ___________________________________________ Director ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ Department Chairperson ___________________________________________ Program Director ___________________________________________ Dean, College of Humanities and Social Sciences Date: _____________________________________ Spring Semester 2017 George Mason University Fairfax, VA Economics of Illicit Behaviors: Exchange in the Internet Wild West A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at George Mason University By Julia R. Norgaard Master of Arts George Mason University, 2015 Bachelor of Arts University of San Diego, 2012 Director: Dr. Thomas Stratmann, Professor and Dissertation Chair Department of Economics Spring Semester 2017 George Mason University Fairfax, VA Copyright 2017 Julia R. Norgaard All Rights Reserved ii Dedication This is dedicated to my wonderful parents Clark and Jill, who introduced me to economics and taught me how to be a dedicated scholar and a good and faithful person. iii Acknowledgements Thank you to my family and friends who have supported me throughout my graduate journey. My boyfriend, Ennio, who gave -

(Microsoft Powerpoint

KUINKAS SITTEN KÄVIKÄÄN? Kryptomarkkinoiden pökerryttävä historia ja arvaamaton tulevaisuus Antti Järventaus Lähihistoria Darknetin kasvu TOR-KÄYTTÄJIEN MÄÄRÄ GOOGLE-HAUT TERMILLÄ ”DARKNET” BITCOININ ARVO Rakennus- palikat Anonyymi- verkot Virtuaali Krypto- Salaus- valuutat markkinat teknologia Kauppa- paikka- teknologia Historia pähkinänkuoressa > 100 000 GAWKER & SILK ROAD TAPAUS ULBRICHT HUUMELISTAUSTA SEN. SCHUMER SULJETAAN & OP. ONYMOUS 32 000 42 000 SILK ROAD HUUMELISTAUSTA ALOITTAA 01/2011 01/2012 01/2013 01/2014 01/2015 01/2016 FOORUMIT, FARMER’S MARKET OLIGOPOLI: SILK ROAD, BLACK MARKET RELOADED, ATLANTIS 30 40 60 50 MONIPUOLISTUMINEN ??? Nykytila Markkinapaikat ja tuotteet Markkinapaikat Markkinapaikka Markkinapaikan URL Forumin URL Subreddit Alphabay http://pwoah7foa6au2pul.onion http://pwoah7foa6au2pul.onion/forum http://www.reddit.com/r/AlphaBay/ Dream Market http://lchudifyeqm4ldjj.onion http://tmskhzavkycdupbr.onion Valhalla (Silkkitie) http://valhallaxmn3fydu.onion http://thehub7gqe43miyc.onion/index.php?board=37.20 Hansa Market http://hansamkt2rr6nfg3.onion http://www.reddit.com/r/HansaMarket Outlaw Market http://outfor6jwcztwbpd.onion http://outforumbpapnpqr.onion http://www.reddit.com/r/Outlaw_Market Python Market http://25cs4ammearqrw4e.onion http://25cs4ammearqrw4e.onion https://www.reddit.com/r/PythonMarket/ Acropolis Market http://acropol4ti6ytzeh.onion http://acropolhwczbgbkh.onion http://www.reddit.com/r/AcropolisMarket Dr. D's Market http://drddrddig5z3524v.onion Tochka http://tochka3evlj3sxdv.onion Built-in -

The Payments Ecosystem: Security Challenges in the 21St Century

The Payments Ecosystem: Security Challenges in the 21st Century Phil Smith III Senior Architect & Product Manager, Mainframe & Enterprise Distinguished Technologist Micro Focus International Agenda A Short History of Payments The Payments Landscape Today Anatomy of a Card Swipe Card Fraud: How It Happens Protecting Yourself and Your Company Evolution (and Intelligent Design?) A Short History of Payments In the Beginning… Early Currencies Large Purchases Small Purchases Purchases on Yap (island of stone money) Evolution • “Lighter than goats!” • Chek invented: Persia, 550–330 BC • Achaemenid Empire (remember them?) • India, Rome, Knights Templar used cheques More Modern Uses • Cheques revived in 17th century England • Soon after: preprinted, numbered, etc. • Magnetic Ink Character Recognition added in 1960s MICR Modern Payments Systems Many Alternatives to Checks • Not the only game in town any more… • Online payment services (PayPal, WorldPay…) • Electronic bill payments (Internet banking et sim.) • Wire transfer (local or international) • Direct credit, initiated by payer: ACH in U.S. giro in Europe • Direct debit, initiated by payee • Debit cards • Credit cards We’ll focus on these • …and of course good ol’ cash! Charge Cards vs Credit Cards • Terms often interchanged, but quite different • Charge cards must be paid off that month • Credit cards offer “revolving credit” • Credit card actually “invented” back in 1888: “… a credit card issued him with which he procures at the public storehouses, found in every community, whatever he desires -

The Deep Dark

THE DEEP DARK WEB Pierluigi Paganini—Richard Amores Published by Paganini Amores at Smashwords Copyright 2012 Paganini–Amores The Deep Dark Web - paganini/amores publishing 212 providence St, West Warwick, RI 02893 - 401-400-2932 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. This book contains material protected under International and Federal Copyright Laws and Treaties. Any unauthorized reprint or use of this material is prohibited. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system without express written permission from the author / publisher. The information in this book is distributed on an “As Is and for educational only” basis, without warranty. While every precaution has been taken in the preparation of this work, neither the author nor Paganini-Amores publishing. shall have any liability to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the information contained in this book. ISBN: 9781301147106 Publisher – Paganini – Amores For information on book distributors or translations, please contact Publisher Paganini –Amores 212 Providence St Rhode Island 02893 Or Via Dell'Epomeo 180 Parco del Pino Fab.C Sc. A 80126 - Napoli (ITALY) Phone 401-400-2932 – [email protected] deepdarkweb.com – uscyberlabs.com – securityaffairs.co Graphics Designer – Gianni Motta was born in Naples in 1977. He is a creative with over ten years in the field of communication, graphic and web designer. Currently he is in charge for Communication Manager in a cyber security firm. -

The Dark Web

THE DARK WEB FOR THE RATIONAL linkcabin The Dark Web For The Rational I dedicate this book to the late Heather Heyer, Barnaby Jack, Aaron Swartz and Jo Cox. 1 The Dark Web For The Rational ABOUT THE AUTHOR My first name is Jack. I am a security researcher who is interested in many subjects not only limited to IT security. I aim to make positive changes in the world for the vast amount of people and not a small pocket of people. This book was written while I was in university and also after I graduated. Website: https://itsjack.cc Twitter: https://twitter.com/linkcabin ABOUT THE COVER The cover was made by selecting all of the client side code from a popular ‘dark market’ forum and appending it into the image of the ‘Silk Road’ camel commonly associated with the famous ‘Silk Road dark market’ which was run by Ross Ulbricht. The code is appended by using a hex editor, which is then later viewed by an early version of MS paint which renders the appended client side code into a distorted form. This was then copied and stretched to produce the background of the cover, essentially providing a visual representation of the HTML/CSS/JS code from the ‘dark market’. The ‘Silk Road’ camel was then put on top of the distorted background. 2 The Dark Web For The Rational Contents The Birth ...................................................................................................................................................................... 7 MEDIA ........................................................................................................................................................................... -

Internet-Facilitated Drugs Trade

Internet-facilitated drugs trade An analysis of the size, scope and the role of the Netherlands Kristy Kruithof, Judith Aldridge, David Décary-Hétu, Megan Sim, Elma Dujso, Stijn Hoorens For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR1607 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif., and Cambridge, UK R® is a registered trademark. © 2016 WODC, Ministerie van Veiligheid en Justitie Cover image shared by Jo Naylor via Flickr; CC BY 2.0. RAND Europe is an independent, not-for-profit policy research organisation that aims to improve policy and decisionmaking in the public interest through research and analysis. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the sponsor. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org www.rand.org/randeurope Preface The potential role of the Internet in facilitating drugs trade first gained mass attention with the rise and fall of Silk Road; the first major online market place for illegal goods on the dark web. After Silk Road was taken down by the FBI in October 2013, it was only a matter of weeks before copycats filled the void. Today, there are around 50 so-called cryptomarkets and vendor shops where vendors and buyers find each other anonymously to trade illegal drugs, new psychoactive substances, prescription drugs and other goods and services. -

Önder Gürbüz

Önder Gürbüz Tadında, bir kılavuz ki rehber olsun sana. Ne uzun uzadıya nede çok kısa, içinde fuhuşta var, silahta. Esrar ve gizli ilimler, gizliden gizliye bilgiler, belgeler. Bilinmeyenler, gizemin en karanlığı. Ruhum dediğimde, dünyanın bir köşesinden diğerine! Saniyeler içeresinde, yeryüzünden, güneş pırıltısına, yedi kat yerin dibine. http://www.gurbuz.net http://wordpress.gurbuz.net 26.07.2016 Daha Facebook’da yazıp çizerken birisi bana sormuştu “bilgileri nasıl elde ediyorsun?” diye… Yasal zemin dururken yasadışı hareket etmenin âlemi yok… Ancak bu yöntemler ile bir sonuca varamazsanız eğer başka yöntemlere başvurulabilir! Birinci ve en önemli kural: Ne aradığınız hakkında bir fikriniz olmalı… Sonra kelime dağarcığınızda belli oranda kelimelerin mevcudiyeti çok önemli. Son olarak Boole Cebir’i denen operatörlerin kullanımını bilmelisiniz. Çok kısa bir hatırlatmada bulundum çünkü bu konu hakkında gerçekten çok yazmıştım. Benim niyetim buradan uzun uzun ahkâm kesmek değil elinize bir nevi kılavuz, rehber vermek. Online Anonymisierungsdienst ∙ Anonymizer ∙ Anonimleştirme (kimliğinizi, IP adresinizi gizleme) https://www.proxymus.de/ http://anonymouse.org/anonwww_de.html https://hide.me/de/proxy Başka bir yöntem ki aslında hem basit hem etkili, yani en azından yasadışı bir niyetiniz yoksa hedef adresinize birkaç arama motoru üzerinden gitmeniz. Örnek vermek gerekirse… Mesela beni arıyorsunuz, Önder Gürbüz. Arama hedefiniz benim, Google üzerinden Bing’i, Bing üzerinden Yahoo ve Yahoo üzerinden beni arıyorsunuz. Ne kadar çok arama motoru -

Measuring the Longitudinal Evolution of the Online Anonymous

Measuring the Longitudinal Evolution of the Online Anonymous Marketplace Ecosystem Kyle Soska and Nicolas Christin, Carnegie Mellon University https://www.usenix.org/conference/usenixsecurity15/technical-sessions/presentation/soska This paper is included in the Proceedings of the 24th USENIX Security Symposium August 12–14, 2015 • Washington, D.C. ISBN 978-1-939133-11-3 Open access to the Proceedings of the 24th USENIX Security Symposium is sponsored by USENIX Measuring the Longitudinal Evolution of the Online Anonymous Marketplace Ecosystem Kyle Soska and Nicolas Christin Carnegie Mellon University ksoska, nicolasc @cmu.edu { } Abstract and sellers could meet and conduct electronic commerce transactions in a manner similar to the Amazon Market- February 2011 saw the emergence of Silk Road, the first place, or the fixed price listings of eBay. The key inno- successful online anonymous marketplace, in which buy- vation in Silk Road was to guarantee stronger anonymity ers and sellers could transact with anonymity properties properties to its participants than any other online mar- far superior to those available in alternative online or of- ketplace. The anonymity properties were achieved by fline means of commerce. Business on Silk Road, pri- combining the network anonymity properties of Tor hid- marily involving narcotics trafficking, rapidly boomed, den services—which make the IP addresses of both the and competitors emerged. At the same time, law enforce- client and the server unknown to each other and to out- ment did not sit idle, and eventually managed to shut side observers—with the use of the pseudonymous, de- down Silk Road in October 2013 and arrest its operator. -

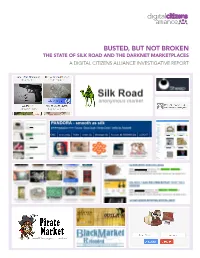

Busted, but Not Broken

BUSTED, BUT NOT BROKEN THE STATE OF SILK ROAD AND THE DARKNET MARKETPLACES A DIGITAL CITIZENS ALLIANCE INVESTIGATIVE REPORT Ten months ago, the Digital Citizens Alliance began researching illicit online marketplaces, including Silk Road (pre- and post-arrest of Ross Ulbricht, accused of being Silk Road’s notorious operator “Dread Pirate Roberts”). This report details the findings of Digital Citizens researchers, including the following key takeaways: Key takeaways: • Approximately 13,648 listings for drugs are now available on Silk Road compared to the 13,000 that were listed shortly before the FBI arrested Ulbricht and shut down the site. In comparison, Silk Road’s closest competitor, Agora, has just roughly 7,400 drug listings. • There is significantly more competition today than when the original Silk Road was seized. Silk Road 2.0 currently contains 5% more listings for drugs than its predecessor held at the time of its seizure. By comparison, the Darknet drug economy as a whole contains 75% more listings for drugs. • Silk Road and other Darknet marketplaces continue to do steady business despite the arrests of additional alleged operators who authorities say worked for Ulbricht. • A series of scam markets, which appeared as opportunists tried to fill the void while the original Silk Road was shut down, created distrust among customers after the operators allegedly stole tens of millions of dollars worth of bitcoin. It is speculated that the resulting distrust may be one of the factors helping Silk Road rebuild its user base so quickly. • In chat rooms used by both operators and customers, many believe that the fallout from Ulbricht’s arrest is complete.