Occidental Impressions of the Sultanate Architecture of Chanderi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Peste-Des-Petits-Ruminants: an Indian Perspective

Advances in Animal and Veterinary Sciences Review Article Peste-Des-Petits-Ruminants: An Indian Perspective 1* 1 1 DHANAVELU MUTHUCHELVAN , KAUSHAL KISHOR RAJAK , MUTHANNAN ANDAVAR RAMAKRISHNAN , 1 1 2 1 DHEERAJ CHOUDHARY , SAKSHI BHADOURIYA ,PARAMASIVAM SARAVANAN , AWADH BIHARI PANDEY , 3 RAJ KUMAR SINGH 1Division of Virology, Indian Veterinary Research Institute, Mukteswar Campus, Nainital, Uttarakhand 263 138, India; 2Indian Veterinary Research Institute, Hebbal Bengaluru, 560024, Karnataka, India; 3Indian Veterinary Research Institute, Izatnagar, 243122, India. Abstract | Peste-des-petits-ruminants (PPR) is an acute or subacute, highly contagious viral disease of small rumi- nants, characterized by fever, oculonasal discharges, stomatitis, diarrhoea and pneumonia with high morbidity and mortality. Peste-des-petits-ruminants virus (PPRV), the etiological agent of PPR, is antigenically related to another rinderpest virus (RP) which was globally eradicated. PPR is gaining worldwide attention through the concerted effort of scientists working together under the aegis of global PPR research alliance (GPRA). The first homologous live at- tenuated vaccine was developed using Nigeria 75/1, which has been used worldwide. In India, live attenuated vaccines have been developed using Sungri 96, Arasur 87 and Coimbatore 97 viruses. In this review, the status of PPR and control strategy with special reference to the Indian context is comprehensively discussed. Keywords | PPR, PPRV, Vaccine, DIVA, Eradication, Symptoms, Epidemiology, Diagnosis, Vaccines, Immunity, Control programme, Replication Editor | Muhammad Munir (DVM, PhD), Avian Viral Diseases Program, Compton Laboratory, Newbury, Berkshire, RG20 7NN, UK. Received | April 27, 2015; Revised | June 16, 2015; Accepted | June 18, 2015; Published | June 24, 2015 *Correspondence | Dhanavelu Muthuchelvan, Indian Veterinary Research Institute, Nainital, Uttarakhand, India; Email: [email protected] Citation | Muthuchelvan D, Rajak KK, Ramakrishnan MA, Choudhary D, Bhadouriya S, Saravanan P, Pandey AB, Singh RK (2015). -

Bank Wise-District Wise Bank Branches (Excluding Cooperative

Bank wise-District wise Bank Branches (Excluding Cooperative Bank/District No. of Branches Allahabad Bank 205 Agar-Malwa 2 Anuppur 2 Balaghat 4 Bhopal 25 Burhanpur 1 Chhatarpur 3 Chhindwara 8 Damoh 3 Datia 1 Dewas 1 Dhar 1 Dindori 1 East Nimar 1 Gwalior 3 Harda 1 Hoshangabad 3 Indore 12 Jabalpur 24 Katni 6 Mandla 4 Mandsaur 2 Morena 1 Narsinghpur 7 Neemuch 2 Panna 3 Raisen 1 Rajgarh 2 Ratlam 2 Rewa 16 Sagar 6 Satna 28 Sehore 2 Seoni 2 Shahdol 3 Shajapur 1 Shivpuri 2 Sidhi 5 Singrauli 6 Tikamgarh 1 Ujjain 2 Vidisha 4 West Nimar 1 Andhra Bank 45 Betul 1 Bhind 1 Bhopal 8 Burhanpur 1 Chhindwara 1 Dewas 1 Dhar 1 East Nimar 1 Gwalior 2 Harda 1 Hoshangabad 2 Indore 11 Jabalpur 3 Katni 1 Narsinghpur 2 Rewa 1 Sagar 1 Satna 1 Sehore 2 Ujjain 1 Vidisha 2 Au Small Finance Bank Ltd. 37 Agar-Malwa 1 Barwani 1 Betul 1 Bhopal 2 Chhatarpur 1 Chhindwara 2 Dewas 2 Dhar 2 East Nimar 1 Hoshangabad 1 Indore 2 Jabalpur 1 Katni 1 Mandla 1 Mandsaur 2 Neemuch 1 Raisen 2 Rajgarh 1 Ratlam 2 Rewa 1 Satna 1 Sehore 2 Shajapur 1 Tikamgarh 1 Ujjain 1 Vidisha 2 West Nimar 1 Axis Bank Ltd. 136 Agar-Malwa 1 Alirajpur 1 Anuppur 1 Ashoknagar 1 Balaghat 1 Barwani 3 Betul 2 Bhind 1 Bhopal 20 Burhanpur 1 Chhatarpur 1 Chhindwara 2 Damoh 1 Datia 1 Dewas 1 Dhar 4 Dindori 1 East Nimar 1 Guna 2 Gwalior 10 Harda 1 Hoshangabad 3 Indore 26 Jabalpur 5 Jhabua 2 Katni 1 Mandla 1 Mandsaur 1 Morena 1 Narsinghpur 1 Neemuch 1 Panna 1 Raisen 2 Rajgarh 2 Ratlam 2 Rewa 1 Sagar 3 Satna 2 Sehore 1 Seoni 1 Shahdol 1 Shajapur 2 Sheopur 1 Shivpuri 2 Sidhi 2 Singrauli 2 Tikamgarh 1 Ujjain 5 Vidisha 2 West Nimar 4 Bandhan Bank Ltd. -

The Place of Performance in a Landscape of Conquest: Raja Mansingh's Akhārā in Gwalior

South Asian History and Culture ISSN: 1947-2498 (Print) 1947-2501 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rsac20 The place of performance in a landscape of conquest: Raja Mansingh’s akhārā in Gwalior Saarthak Singh To cite this article: Saarthak Singh (2020): The place of performance in a landscape of conquest: Raja Mansingh’s akhārā in Gwalior, South Asian History and Culture, DOI: 10.1080/19472498.2020.1719756 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/19472498.2020.1719756 Published online: 30 Jan 2020. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 21 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rsac20 SOUTH ASIAN HISTORY AND CULTURE https://doi.org/10.1080/19472498.2020.1719756 The place of performance in a landscape of conquest: Raja Mansingh’s akhārā in Gwalior Saarthak Singh Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, New York, NY, USA ABSTRACT KEYWORDS In the forested countryside of Gwalior lie the vestiges of a little-known akhārā; landscape; amphitheatre (akhārā) attributed to Raja Mansingh Tomar (r. 1488–1518). performance; performativity; A bastioned rampart encloses the once-vibrant dance arena: a circular stage dhrupad; rāsalīlā in the centre, surrounded by orchestral platforms and an elevated viewing gallery. This purpose-built performance space is a unique monumentalized instance of widely-prevalent courtly gatherings, featuring interpretive dance accompanied by music. What makes it most intriguing is the archi- tectural play between inside|outside, between the performance stage and the wilderness landscape. -

Mandsaur PDF\2316

CENSUS OF INDIA 2011 MADHYA PRADESH SERIES -24 PART XII-A DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK MANDSAUR VILLAGE AND TOWN DIRECTORY DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS MADHYA PRADESH 2011 INDIA MADHYA PRADESH DISTRICT MANDSAUR To Kota To Chittorgarh N KILOMETRES To Kota !GANDHI SAGAR 4 2 0 4 8 12 16 HYDEL COLONY A C.D. B L O C K From Rampura B H A N P U R A H G To Kota A ! Sandhara BHANPURA To C Jhalrapatan ! J H U RS . R l J a b M !! Bhensoda ! ! ! ! m ! ! ! a ! h ! C ! ! E ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! From Neemuch ! ! ! R ! ! ! ! ! I ! ! E ! ! T T C ! T N From Ajmer S C To Mandsaur I GAROTH RS ! ! ! J ( D ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! MALHARGARH ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! From Jiran ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! C.D. B L O C K G ! A R O T H ! ! ( NARAYANGARH ! G ! ! R ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Boliya ! B ! To Kotri ! ! G !! ! ! ! Budha ! S ! ! ! RS ! ! ! ! ! D ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Chandwasa C.D. B L O C K M A L H A R G A R H ! ! ! . ! ! ! ! SHAMGARH Sh a R ! ! i vn ! N PIPLYA MANDI ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! R RS G ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! J ! ! RS ! ! ! Nahargarh ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! . ! ! ! ! ! ! ! RS ! G ! ! ! ! R A ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! l ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! a ! NH79 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! b ! ! ! ! ! ! ! m ! G ! ! ! a ! ! ! ! )M ! Kayampur h ! Multanpura ! H C A ! ! G)E ! SUWASRA H ! ! ! ! ! ! ! MANDSAUR ! G R ! RS P ! ! ! ( ! ! ! ! ! ! SH 14 ! C.D. B L O C K S I T A M A U ! ! E ! T ! ! SITAMAU ! Kilchipura !! ! ! ( R From ! ! ! ! G ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Pratappur ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! Ladoona ! ! ! ! ! J ! ! ! S ! ! -

In the Heart of India

Au coeur de l'Inde Jours: 16 Prix: 1480 EUR Vol international non inclus Confort: Difficulté: Culture Ce voyage de seize jours au cœur de deux grands états de l’Inde centrale, le Madhya Pradesh et le Maharashtra, offre différents aspects. Dédié principalement au patrimoine architectural, il nous conduit sur les traces des anciens empires et offre, en cours de route, de magnifiques paysages. Notre voyage démarre dans la capitale indienne. Agra est la première étape du chemin du patrimoine. Le fort rouge et le Taj Mahal, véritable incarnation de l’amour, constituent les principaux monuments. Etape suivante, Gwalior, où le fort et ses dépendances en parfait état, abritent de très nombreux édifices historiques : temples, palais et réservoirs. La route, entre Gwalior et Khajuraho, donne l’occasion de visiter de petites bourgades, importantes sur le plan historique, telles Orcha ou Datia. Les sculptures, érotiques ou autres, ornant les murs des trois groupes de temples de Khajurao (tous inscrits au patrimoine mondial de l’humanité), sont certainement parmi les plus belles au monde. Près de Bhopal, halte au remarquable stupa de Sanchi, bel exemple d’architecture bouddhiste. D’autres étapes méritent une halte : Indore, Ujjain, Dhar, Mandu avant d’arriver à Aurangabad. La cité, qui doit son nom à l’illustre empereur moghol Aurangzeb, constitue le point de départ idéal pour explorer les célèbres grottes bouddhistes d’Ajanta et d’Ellora. Creusées dans le basalte entre les VI° et VIII° siècles, les artistes bouddhistes les ont remarquablement décorées. Après cette immersion historique, envol pour Mumbai. Le cœur de la cité a vu s’ériger quelques-uns des plus majestueux bâtiments coloniaux, mais il faut prendre le temps d’explorer les bazars, les temples hindous, les enclaves hipsters… Ici notre voyage se termine. -

List of Cooperative Societies / Banks Registered Under MSCS Act W.E.F. 1986 Onwards Principal Date of Registration No

List of Cooperative Societies / Banks registered under MSCS Act w.e.f. 1986 onwards Principal Date of Registration No. S No Name of the Cooperative and its address Area of operation Type Remarks place Registration and file No. 1 All India Scheduled Castes Development Coop. Society All India Delhi 5.9.1986 MSCS Act/CR-1/86 Welfare Ltd.11, Race Course Road, New Delhi 110003 L.11015/3/86-L&M 2 Tribal Cooperative Marketing Development federation All India Delhi 6.8.1987 MSCS Act/CR-2/87 Marketing of India(TRIFED), Savitri Sadan, 15, Preet Vihar L.11015/10/87-L&M Community Center, Delhi 110092 3 All India Cooperative Cotton Federation Ltd., C/o All India Delhi 3.3.1988 MSCS Act/CR-3/88 Federation National Agricultural Cooperative Marketing L11015/11/84-L&M Federation of India Ltd. Sapna Building, 54, East of Kailash, New Delhi 110065 4 The British Council Division Calcutta L/E Staff Co- West Bengal, Tamil Kolkata 11.4.1988 MSCS Act/CR-4/88 Credit Converted into operative Credit Society Ltd , 5, Shakespeare Sarani, Nadu, Maharashtra & L.11016/8/88-L&M MSCS Kolkata, West Bengal 700017 Delhi 5 National Tree Growers Cooperative Federation Ltd., A.P., Gujarat, Odisha, Gujarat 13.5.1988 MSCS Act/CR-5/88 Credit C/o N.D.D.B, Anand-388001, District Kheda, Gujarat. Rajasthan & Karnataka L 11015/7/87-L&M 6 New Name : Ideal Commercial Credit Multistate Co- Maharashtra, Gujarat, Pune 22.6.1988 MSCS Act/CR-6/88 Amendment on Operative Society Ltd Karnataka, Goa, Tamil L 11016/49/87-L&M 23-02-2008 New Address: 1143, Khodayar Society, Model Nadu, Seemandhra, & 18-11-2014, Colony, Near Shivaji Nagar Police ground, Shivaji Telangana and New Amend on Nagar, Pune, 411016, Maharashtra 12-01-2017 Delhi. -

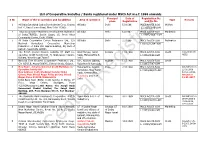

Expenditure Incurred on Historical Monuments / Sites for Conservation and Preservation During the Last Five Year and Current Ye

Expenditure incurred on Historical Monuments / Sites for Conservation and Preservation during the last Five year and current year upto September2011 Monument wise under the Jurisdiction of Bhopal Circle, Bhopal in Madhya Pradesh SNo Name of the Monuments Site Location 2006-07 2007-08 2008-09 2009-10 2010-11 2011 -12 upto September Locality District State Plan Non Plan Plan Non Plan Plan Non Plan Plan Non Plan Plan Non Plan Plan Non Plan 1 Karan Temple Amarkantak Anuppur M.P. 3,85,736/- 22,981/- 11,05,211/ 48,341/ 4,85,019 8,11,410/- 5,040/- 2,58,537/- 3,21,231/- 2,93,058/- 39846.00 38948.00 2 Siva Temple Amarkantak Anuppur M.P. 6,03,581/- 3,15,129/- 6,09,534/- 29,381/- 2,79,578/- 3,65,730/- 2,830/- 6,21,514/- 3,900/- 1,35,990/- 439220.00 89997.00 3 Temple of Patalesvara Amarkantak Anuppur M.P. 00.00 6,14,615/- 12,261/- 65,432/- 12,261/- 7,42,249/- 12,23,534/- 5,87,165/- 3,17,994/- 3,57,695/- 73120.00 35461.00 4 Caves bearing inscriptions of Silhara Anuppur M.P. 00.00 10,797/- 00.00 13,300/- 00.00 00.00 00.00 3,500/- 00.00 50,210/- 00.00 7235.00 1st century AD 5 Jain Temples 1 to 5 Budichan-deri Ashok Nagar M.P. 00.00 43,862/- 00.00 1,07,485/- 00.00 00.00 00.00 97,829/- 00.00 2,00,038/- 00.00 98841.00 6 Chanderi Fort Chanderi Ashok Nagar M.P. -

ANSWERED ON:06.02.2017 E-Ticketing at Monuments Gavit Dr

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA CULTURE LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO:659 ANSWERED ON:06.02.2017 e-Ticketing at Monuments Gavit Dr. Heena Vijaykumar;Jayavardhan Dr. Jayakumar;Mahadik Shri Dhananjay Bhimrao;Patil Shri Vijaysinh Mohite;Satav Shri Rajeev Shankarrao;Sule Smt. Supriya Sadanand Will the Minister of CULTURE be pleased to state: (a) whether the Government has launched e-ticketing facility at Monuments to provide an online booking facility for foreign and domestic visitors and if so, the details thereof; (b) whether this facility is introduced in all the monuments and if so, the details thereof vis-a-vis the number of monuments of ASI where fees are charged from visitors to visit the monuments; (c) whether the Government is also in the process to procure hardware to have computerized facility for the sale of e-tickets at monuments and if so, the details thereof; and (d) whether the Government has launched a portal in this regard and if so, the details thereof? Answer MINISTER OF STATE, (INDEPENDENT CHARGE) CULTURE & TOURISM (DR. MAHESH SHARMA) (a) Yes Madam, the E-ticketing facilities have already introduced on 116 ticketed monuments with effect from 25th December, 2015. The online ticketing system is in operation for 109 ticketed monuments / sites out of 116 ticketed monuments under Archaeological Survey of India. Details are given at Annexure-1. (b) There are 116 ticketed monuments / sites out of 3687 monuments / sites of national importance under ASI where fees are being charged from the visitors for visiting these monuments. Details are given at Annexure-2. (c) The hardware has already been procured for facilitating computerize E-ticketing at all 116 ticketed monuments / sites. -

4. Maharashtra Before the Times of Shivaji Maharaj

The Coordination Committee formed by GR No. Abhyas - 2116/(Pra.Kra.43/16) SD - 4 Dated 25.4.2016 has given approval to prescribe this textbook in its meeting held on 3.3.2017 HISTORY AND CIVICS STANDARD SEVEN Maharashtra State Bureau of Textbook Production and Curriculum Research, Pune - 411 004. First Edition : 2017 © Maharashtra State Bureau of Textbook Production and Curriculum Research, Reprint : September 2020 Pune - 411 004. The Maharashtra State Bureau of Textbook Production and Curriculum Research reserves all rights relating to the book. No part of this book should be reproduced without the written permission of the Director, Maharashtra State Bureau of Textbook Production and Curriculum Research, ‘Balbharati’, Senapati Bapat Marg, Pune 411004. History Subject Committee : Cartographer : Dr Sadanand More, Chairman Shri. Ravikiran Jadhav Shri. Mohan Shete, Member Coordination : Shri. Pandurang Balkawade, Member Mogal Jadhav Dr Abhiram Dixit, Member Special Officer, History and Civics Shri. Bapusaheb Shinde, Member Varsha Sarode Shri. Balkrishna Chopde, Member Subject Assistant, History and Civics Shri. Prashant Sarudkar, Member Shri. Mogal Jadhav, Member-Secretary Translation : Shri. Aniruddha Chitnis Civics Subject Committee : Shri. Sushrut Kulkarni Dr Shrikant Paranjape, Chairman Smt. Aarti Khatu Prof. Sadhana Kulkarni, Member Scrutiny : Dr Mohan Kashikar, Member Dr Ganesh Raut Shri. Vaijnath Kale, Member Prof. Sadhana Kulkarni Shri. Mogal Jadhav, Member-Secretary Coordination : Dhanavanti Hardikar History and Civics Study Group : Academic Secretary for Languages Shri. Rahul Prabhu Dr Raosaheb Shelke Shri. Sanjay Vazarekar Shri. Mariba Chandanshive Santosh J. Pawar Assistant Special Officer, English Shri. Subhash Rathod Shri. Santosh Shinde Smt Sunita Dalvi Dr Satish Chaple Typesetting : Dr Shivani Limaye Shri. -

A Case of City of Joy Maandav, Dist. Dhar, Madhya Pradesh

International Journal of Innovations in Engineering and Technology (IJIET) http://dx.doi.org/10.21172/ijiet.124.02 Legacy That Historic Cities Carry: A Case of City of Joy Maandav, Dist. Dhar, Madhya Pradesh Ar. Garima Sharma1, Dr. S.S. Jadon2 1,2Department of Architecture & Planning, MITS, Gwalior, Madhya Pradesh, India Abstract- India is home to more than 300 historic cities with very unique character in each of them. These cities carry a legacy since times immemorial, of art, culture, tradition, architecture, planning, engineering, ancient forms and so on. Historic cities are best understood through understanding basics of heritage, land, context & cities. Heritage : Heritage is what we inherit from our ancestors & from our past Land: The land & the people are two integral components of the heritage. Indian context: Heritage in India is result of development in the society, economy, culture, architecture & lifestyle of the people Cities: Those active human settlements strongly conditioned by a physical structure originating in the past & recognizable as representing the evolution of its people (Source: S. Mutal) This definition recognizes that a historical city is not constituted only by a material and physical heritage. It comprises not only Buildings, Streets, Squares, Fountains, Arches, Sculptures, Lamp posts but includes the natural landscape, and of course: • Its residents, • Customs, • Jobs, • Economic and social relations, • Beliefs and urban rituals. This definition also includes the important presence of the past and understands by “historical” all those cultural, architectural, and urban expressions which are recognized as relevant and which express the social and cultural life of a community. It eliminates any selection based on restricted interpretation of the term historical and an outlook which places more value on past periods of history. -

Printpdf/Madhya-Pradesh-Public-Service-Commission-Mppcs-Gk-State-Pcs-English

Drishti IAS Coaching in Delhi, Online IAS Test Series & Study Material drishtiias.com/printpdf/madhya-pradesh-public-service-commission-mppcs-gk-state-pcs-english Madhya Pradesh Public Service Commission (MPPCS) GK Madhya Pradesh GK Formation 1st november, 1956 Capital Bhopal Population 7,26,26,809 Region 3,08,252 sq. km. Population density in state 236 persons per sq.km. Total Districts 52 (52nd District – Niwari) Other Name of State Hriday Pradesh, Soya State, Tiger State, Leopard State High Court Jabalpur (Bench – Indore, Gwalior) 1/16 State Symbol State Animal: State Flower: Barahsingha (reindeer) White Lily State Bird: State Dance: Dudhraj (Shah Bulbul) Rai 2/16 State Tree: Banyan Official Game: Malkhamb Madhya Pradesh : General Information State – Madhya Pradesh Constitution – 01 November, 1956 (Present Form – 1 November 2000) Area – 3,08,252 sq. km. Population – 7,26,26,809 Capital – Bhopal Total District – 52 No. of Divisions – 10 Block – 313 Tehsil (January 2019) – 424 The largest tehsil (area) of the state – Indore The smallest tehsil (area) of the state – Ajaygarh (Panna) Town/city – 476 Municipal Corporation (2018-19) – 16 Municipality – 98 City Council – 294 Municipality – 98 (As per Government Diary 2021: 99) Total Village – 54903 Zilla Panchayat – 51 Gram Panchayat – 22812 (2019–20) Tribal Development Block – 89 State Symbol – A circle inside the 24 stupa shape, in which there are earrings of wheat and paddy. State River – Narmada State Theater – Mach Official Anthem – Mera Madhya Pradesh Hai (Composer – Mahesh Srivastava) -

Heritage Madhya Pradesh Top Sights • Food • Shopping

A guide to heritage trips in Madhya Pradesh HERITAGE H eritage MADHYA M adhya PRADESH P TOP SIGHTS • FOOD • SHOPPING radesh All you need to know about Madhya Pradesh • Top historic destinations of Madhya Pradesh • Options for staying, eating and shopping • Everything you need to know while planning a trip • Tips on music, art, cuisine and festivals of the state WHY YOU CAN TRUST US... World’s Our job is to make amazing travel Leading experiences happen. We visit the places Travel we write about each and every edition. We Expert never take freebies for positive coverage, so 1ST EDITION Published January 2018 you can always rely on us to tell it like it is. Not for sale HERITAGE MADHYA PRADESH TOP SIGHTS • FOOD • SHOPPING This guide is researched and written by Supriya Sehgal Contents Need to Know ............................................................ 04 Best Trips Gwalior ............................................................................. 06 Orchha .............................................................................. 12 Khajuraho ......................................................................... 18 Bhopal ...............................................................................28 Sanchi ...............................................................................34 Mandu ...............................................................................38 Burhanpur ........................................................................44 Index ............................................................................48