Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Casting Directors Network Index

International Casting Directors Network Index 01 Welcome 02 About the ICDN 04 Index of Profiles 06 Profiles of Casting Directors 76 About European Film Promotion 78 Imprint 79 ICDN Membership Application form Gut instinct and hours of research “A great film can feel a lot like a fantastic dinner party. Actors mingle and clash in the best possible lighting, and conversation is fraught with wit and emotion. The director usually gets the bulk of the credit. But before he or she can play the consummate host, someone must carefully select the right guests, send out the invites, and keep track of the RSVPs”. ‘OSCARS: The Role Of Casting Director’ by Monica Corcoran Harel, The Deadline Team, December 6, 2012 Playing one of the key roles in creating that successful “dinner” is the Casting Director, but someone who is often over-looked in the recognition department. Everyone sees the actor at work, but very few people see the hours of research, the intrinsic skills, the gut instinct that the Casting Director puts into finding just the right person for just the right role. It’s a mix of routine and inspiration which brings the characters we come to love, and sometimes to hate, to the big screen. The Casting Director’s delicate work as liaison between director, actors, their agent/manager and the studio/network figures prominently in decisions which can make or break a project. It’s a job that can't garner an Oscar, but its mighty importance is always felt behind the scenes. In July 2013, the Academy of Motion Pictures of Arts and Sciences (AMPAS) created a new branch for Casting Directors, and we are thrilled that a number of members of the International Casting Directors Network are amongst the first Casting Directors invited into the Academy. -

Press Release a Tribute To... Award to German Director Tom Tykwer One

Press Release A Tribute to... Award to German Director Tom Tykwer One of Europe’s Most Versatile Directors August 24, 2012 This year’s A Tribute to... award goes to author, director and producer Tom Tykwer. This is the first time that a German filmmaker has ever received one of the Zurich Film Festival’s honorary awards. Tykwer will collect his award in person during the Award Night at the Zurich Opera House. The ZFF will screen his most important films in a retrospective held at the Filmpodium. The ZFF is delighted that one of Europe’s most versatile directors is coming to Zurich. “Tom Tykwer has ensured that German film has once more gained in renown, significance and innovation, both on a national and international level,” said the festival management. Born 1965 in Wuppertal, Tom Tykwer shot his first feature DEADLY MARIA in 1993. He founded the X Filme Creative Pool in 1994 together with Stefan Arndt and the directors Wolfgang Becker and Dani Levy. It is currently one of Germany’s most successful production and distribution companies. RUN LOLA RUN Tykwer’s second cinema feature WINTER SLEEPERS (1997) was screened in competition at the Locarno Film Festival. RUN LOLA RUN followed in 1998, with Franka Potente and Moritz Bleibtreu finding themselves as the protagonists in a huge international success. The film won numerous awards, including the Deutscher Filmpreis in Gold for best directing. Next came THE PRINCESS AND THE WARRIOR (2000), also with Frank Potente, followed by Tykwer’s fist English language production HEAVEN (2002), which is based on a screenplay by the Polish director Krzysztof Kieslowski and stars Cate Blanchett and Giovanni Ribisi. -

Course Outline

Prof. Fatima Naqvi German 01:470:360:01; cross-listed with 01:175:377:01 (Core approval only for 470:360:01!) Fall 2018 Tu 2nd + 3rd Period (9:50-12:30), Scott Hall 114 [email protected] Office hour: Tu 1:10-2:30, New Academic Building or by appointment, Rm. 4130 (4th Floor) Classics of German Cinema: From Haunted Screen to Hyperreality Description: This course introduces students to canonical films of the Weimar, Nazi, post-war and post-wall period. In exploring issues of class, gender, nation, and conflict by means of close analysis, the course seeks to sensitize students to the cultural context of these films and the changing socio-political and historical climates in which they arose. Special attention will be paid to the issue of film style. We will also reflect on what constitutes the “canon” when discussing films, especially those of recent vintage. Directors include Robert Wiene, F.W. Murnau, Fritz Lang, Lotte Reiniger, Leni Riefenstahl, Alexander Kluge, Volker Schlöndorff, Werner Herzog, Wim Wenders, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Andreas Dresen, Christian Petzold, Jessica Hausner, Michael Haneke, Angela Schanelec, Barbara Albert. The films are available at the Douglass Media Center for viewing. Taught in English. Required Texts: Anton Kaes, M ISBN-13: 978-0851703701 Recommended Texts (on reserve at Alexander Library): Timothy Corrigan, A Short Guide to Writing about Film Rob Burns (ed.), German Cultural Studies Lotte Eisner, The Haunted Screen Sigmund Freud, Writings on Art and Literature Siegfried Kracauer, From Caligari to Hitler Anton Kaes, Shell Shock Cinema: Weimar Cinema and the Wounds of War Noah Isenberg, Weimar Cinema Gerd Gemünden, Continental Strangers Gerd Gemünden, A Foreign Affair: Billy Wilder’s American Films Sabine Hake, German National Cinema Béla Balász, Early Film Theory Siegfried Kracauer, The Mass Ornament Brad Prager, The Cinema of Werner Herzog Eric Ames, Ferocious Reality: Documentary according to Werner Herzog Eric Ames, Werner Herzog: Interviews N. -

FLM302 Reading German Film 3 Module Outline 2019-20

FLM302: READING GERMAN FILM 3: CONTEMPORARY GERMAN CINEMA Course Outline, 2019-2020 Semester A 15 credits Course Organiser Dr Alasdair King [email protected] Arts 1: 2.08 Office hours: Wednesday 11-1 Timetable Screenings: Tuesday 10-12, Arts 1 G.34 Lectures: Tuesday 1-2, Bancroft G.07 Seminars: Thursday 2-3, Arts 2 3.17 Course Description This module will allow students to analyse various aspects of German film culture in the new millennium. It explores developments in recent German filmmaking in the context of the increasing globalisation of media industries and images and in the context of contemporary cinema’s relationship to other media forms. Stu- dents will explore the dynamics of recent German cinema, including its successes at major award ceremonies and at film festivals, its relationship to Hollywood and to other international cinemas, its distinct approach to questions of the audience, of auteurism and of production, and to transnational images, particularly con- cerning the emergence of Turkish-German filmmaking. Students will also address the representation of politics, terrorism, history, heritage and the national past, the engagement with issues of performance, gender and sexuality, the use of genre and popular commercial film styles, and the re-emergence of a ‘counter cinema’ in the work of the ‘Berlin School’ and after. Seminar work on current trends will allow students to work independently to research an individual case study of a chosen film and its significance to contemporary German cinema. Recommended Reading Abel, M (2013) The Counter-Cinema of the Berlin School. Rochester, NY: Camden House. -

Through FILMS 70 Years of European History Through Films Is a Product in Erasmus+ Project „70 Years of European History 1945-2015”

through FILMS 70 years of European History through films is a product in Erasmus+ project „70 years of European History 1945-2015”. It was prepared by the teachers and students involved in the project – from: Greece, Czech Republic, Italy, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Spain, Turkey. It’ll be a teaching aid and the source of information about the recent European history. A DANGEROUS METHOD (2011) Director: David Cronenberg Writers: Christopher Hampton, Christopher Hampton Stars: Michael Fassbender, Keira Knightley, Viggo Mortensen Country: UK | GE | Canada | CH Genres: Biography | Drama | Romance | Thriller Trailer In the early twentieth century, Zurich-based Carl Jung is a follower in the new theories of psychoanalysis of Vienna-based Sigmund Freud, who states that all psychological problems are rooted in sex. Jung uses those theories for the first time as part of his treatment of Sabina Spielrein, a young Russian woman bro- ught to his care. She is obviously troubled despite her assertions that she is not crazy. Jung is able to uncover the reasons for Sa- bina’s psychological problems, she who is an aspiring physician herself. In this latter role, Jung employs her to work in his own research, which often includes him and his wife Emma as test subjects. Jung is eventually able to meet Freud himself, they, ba- sed on their enthusiasm, who develop a friendship driven by the- ir lengthy philosophical discussions on psychoanalysis. Actions by Jung based on his discussions with another patient, a fellow psychoanalyst named Otto Gross, lead to fundamental chan- ges in Jung’s relationships with Freud, Sabina and Emma. -

FM 201 Introduction to Film Studies: German Cinema

FM 201 Introduction to Film Studies: German Cinema Seminar Leader: Matthias Hurst Course Times: Monday, 14.00 – 15.30; Tuesday, 19.30 – 22.00 (weekly film screening); Wednesday, 14.00 – 15.30 Email: [email protected] Office Hours: Tuesday, 13.30 – 15.00 Course Description In this introductory class basic knowledge of film history and theory, film aesthetics and cinematic language will be provided; central topics are the characteristics of film as visual form of representation, the development of film language since the beginning of the 20th century, styles of filmic discourse, film analysis and different approaches to film interpretation. The thematic focus will be on German cinema with classical films by Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau, Fritz Lang, Leni Riefenstahl, Wim Wenders, Volker Schlöndorff, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Margarethe von Trotta, Tom Tykwer and others, reflecting historical and cultural experiences and changes in German history and society as well as developments in aesthetics and cinematic style. Foundational module: Approaching Arts Through Theory Credits: 8 ECTS, 4 U.S. credits Requirements No prerequisites. Attendance is mandatory for all seminars and film screenings. Students are expected to come to seminars and film screenings punctually and prepared, to participate actively in the class discussions and to do all the course assignments on time. * Please, do not use cell phones, smart phones or similar electronic devices during seminars and screenings! Academic Integrity Bard College Berlin maintains the staunchest regard for academic integrity and expects good academic practice from students in their studies. Instances in which students fail to meet the expected standards of academic integrity will be dealt with under the Code of Student Conduct, Section III Academic Misconduct. -

The 12Th Annual Jerusalem Pitch Point

The 12th Annual Jerusalem Pitch Point 01. pitchpoint past projects Saving Neta Youth Fill the Void Tikkun In Between Scaffolding That Lovely Girl Zero Motivation Policeman .02 03. SCHEDULE INDUSTRY DAYS EVENTS 2017 SUNDAY, JULY 16th reading of a trade publication from the recent Marché du Film in Cannes, and the large variety of advertising contained within. 10:00-12:15 Are there absolute rules to be followed or mistakes to be avoided? How does one stand out from Pitch Point Production Competition the crowd? How can design allow a project to reach or create an audience without betraying Open to the general public its artistic spirit and creative integrity? Theater 4, Jerusalem Cinematheque 16:00-17:30 13:00-18:45 Based on a True Story – A Documentary Panel Industry Panels Finding a new subject for a documentary film can be very exciting. But after the precious Open to the general public story is found, how do you tell it? Sinai Abt (Kan - Israeli Public Broadcasting Corporation), Theater 4, Jerusalem Cinematheque Joëlle Alexis (Film Editor), Osnat Trabelsi (Israeli Documentary Filmmakers Forum) and Maya Zinshtein (Forever Pure) discuss the ups and downs of “writing” reality, from the blank page to the editing bay. Moderated by Osnat Trabelsi 13:00-14:30 One Film, Many Platforms - A Distribution Panel 17:45-18:45 The “Digital Revolution” has had an effect on every aspect of our lives, including our industry. Jerusalem Through the Director’s Viewfinder - The Quarters Panel Alongside groundbreaking advances in filmmaking, film distribution is in the midst of a digital Four acclaimed international directors – Todd Solondz (Happiness), Anna Muylaert (The Second transformation. -

![Inmedia, 3 | 2013, « Cinema and Marketing » [Online], Online Since 22 April 2013, Connection on 22 September 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3954/inmedia-3-2013-%C2%AB-cinema-and-marketing-%C2%BB-online-online-since-22-april-2013-connection-on-22-september-2020-603954.webp)

Inmedia, 3 | 2013, « Cinema and Marketing » [Online], Online Since 22 April 2013, Connection on 22 September 2020

InMedia The French Journal of Media Studies 3 | 2013 Cinema and Marketing Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/inmedia/524 DOI: 10.4000/inmedia.524 ISSN: 2259-4728 Publisher Center for Research on the English-Speaking World (CREW) Electronic reference InMedia, 3 | 2013, « Cinema and Marketing » [Online], Online since 22 April 2013, connection on 22 September 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/inmedia/524 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/ inmedia.524 This text was automatically generated on 22 September 2020. © InMedia 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Cinema and Marketing When Cultural Demands Meet Industrial Practices Cinema and Marketing: When Cultural Demands Meet Industrial Practices Nathalie Dupont and Joël Augros Jerry Pickman: “The Picture Worked.” Reminiscences of a Hollywood publicist Sheldon Hall “To prevent the present heat from dissipating”: Stanley Kubrick and the Marketing of Dr. Strangelove (1964) Peter Krämer Targeting American Women: Movie Marketing, Genre History, and the Hollywood Women- in-Danger Film Richard Nowell Marketing Films to the American Conservative Christians: The Case of The Chronicles of Narnia Nathalie Dupont “Paris . As You’ve Never Seen It Before!!!”: The Promotion of Hollywood Foreign Productions in the Postwar Era Daniel Steinhart The Multiple Facets of Enter the Dragon (Robert Clouse, 1973) Pierre-François Peirano Woody Allen’s French Marketing: Everyone Says Je l’aime, Or Do They? Frédérique Brisset Varia Images of the Protestants in Northern Ireland: A Cinematic Deficit or an Exclusive -

Set in Scotland a Film Fan's Odyssey

Set in Scotland A Film Fan’s Odyssey visitscotland.com Cover Image: Daniel Craig as James Bond 007 in Skyfall, filmed in Glen Coe. Picture: United Archives/TopFoto This page: Eilean Donan Castle Contents 01 * >> Foreword 02-03 A Aberdeen & Aberdeenshire 04-07 B Argyll & The Isles 08-11 C Ayrshire & Arran 12-15 D Dumfries & Galloway 16-19 E Dundee & Angus 20-23 F Edinburgh & The Lothians 24-27 G Glasgow & The Clyde Valley 28-31 H The Highlands & Skye 32-35 I The Kingdom of Fife 36-39 J Orkney 40-43 K The Outer Hebrides 44-47 L Perthshire 48-51 M Scottish Borders 52-55 N Shetland 56-59 O Stirling, Loch Lomond, The Trossachs & Forth Valley 60-63 Hooray for Bollywood 64-65 Licensed to Thrill 66-67 Locations Guide 68-69 Set in Scotland Christopher Lambert in Highlander. Picture: Studiocanal 03 Foreword 03 >> In a 2015 online poll by USA Today, Scotland was voted the world’s Best Cinematic Destination. And it’s easy to see why. Films from all around the world have been shot in Scotland. Its rich array of film locations include ancient mountain ranges, mysterious stone circles, lush green glens, deep lochs, castles, stately homes, and vibrant cities complete with festivals, bustling streets and colourful night life. Little wonder the country has attracted filmmakers and cinemagoers since the movies began. This guide provides an introduction to just some of the many Scottish locations seen on the silver screen. The Inaccessible Pinnacle. Numerous Holy Grail to Stardust, The Dark Knight Scottish stars have twinkled in Hollywood’s Rises, Prometheus, Cloud Atlas, World firmament, from Sean Connery to War Z and Brave, various hidden gems Tilda Swinton and Ewan McGregor. -

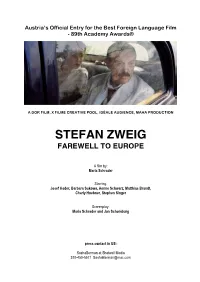

Stefan Zweig Farewell to Europe

Austria’s Official Entry for the Best Foreign Language Film - 89th Academy Awards® A DOR FILM, X FILME CREATIVE POOL, IDÉALE AUDIENCE, MAHA PRODUCTION STEFAN ZWEIG FAREWELL TO EUROPE A film by: Maria Schrader Starring: Josef Hader, Barbara Sukowa, Aenne Schwarz, Matthias Brandt, Charly Huebner, Stephen SInger Screenplay: Maria Schrader and Jan Schomburg press contact in US: SashaBerman at Shotwell Media 310-450-5571 [email protected] Table of Contents Short synopsis & press note …………………………………………………………………… 3 Cast ……............................................................................................................................ 4 Crew ……………………………………………………………………………………………… 6 Long Synopsis …………………………………………………………………………………… 7 Persons Index…………………………………………………………………………………….. 14 Interview with Maria Schrader ……………………………………………………………….... 17 Backround ………………………………………………………………………………………. 19 In front of the camera Josef Hader (Stefan Zweig)……………………………………...……………………………… 21 Barbara Sukowa (Friderike Zweig) ……………………………………………………………. 22 Aenne Schwarz (Lotte Zweig) …………………………….…………………………………… 23 Behind the camera Maria Schrader………………………………………….…………………………………………… 24 Jan Schomburg…………………………….………...……………………………………………….. 25 Danny Krausz ……………………………………………………………………………………… 26 Stefan Arndt …………..…………………………………………………………………….……… 27 Contacts……………..……………………………..………………………………………………… 28 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Technical details Austria/Germany/France, 2016 Running time 106 Minutes Aspect ratio 2,39:1 Audio format 5.1 ! 2! “Each one of us, even the smallest and the most insignificant, -

GN375 Revi Sed _____ Title of Course: the History of German Film New X__

Southeast Missouri State University Depar tment of Foreign Languages Course No. GN375 Revi sed _____ Title of Course: The History of German Film New _ X__ I. Catalog Descr iption and Cr edit Hour s of Cour se: A study of the history of German film from 1919 to the present, including the Weimar Republic, the Third Reich, Post War East and West Germany, and contemporary developments. 3 credit hours II. Pr er equi si t es: German 220 (German Literature) or equivalent or consent of the instructor. III. Cour se Obj ect i ves: A. To introduce the students to the major German film directors and films of the twentieth- century. B. To develop an approach to interpret these films as an outgrowth of their cultural, political, and soci o-economic milieu. C. To gain an understanding of Germany and appreciation of the German-speaki ng world based on their films. IV. Expectations of Students: A. Assignments: Students ar e exp ected to attend al l cl asses, compl ete al l assi gned r eadi ngs, and see al l r equi r ed f i lms. All films shown are in German with English subtitles. Students will see them outside of class. Only short subjects, clips etc. will be shown in class. B. Resear ch Pr oj ect: Students will select one film director or film for their semester project. They pr esent thei r pr oj ect i n Ger man dur i ng the l ast week of cl ass. C. In-Cl ass Repor ts: Students ar e exp ected to compl ete i n-class reports on events in the German- speaki ng world, the assigned readings, and related assignments. -

From Weimar to Winnipeg: German Expressionism and Guy Maddin Andrew Burke University of Winnipeg (Canada) E-Mail: [email protected]

ACTA UNIV. SAPIENTIAE, FILM AND MEDIA STUDIES, 16 (2019) 59–79 DOI: 10.2478/ausfm-2019-0004 From Weimar to Winnipeg: German Expressionism and Guy Maddin Andrew Burke University of Winnipeg (Canada) E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. The films of Guy Maddin, from his debut feature Tales from the Gimli Hospital (1988) to his most recent one, The Forbidden Room (2015), draw extensively on the visual vocabulary and narrative conventions of 1920s and 1930s German cinema. These cinematic revisitations, however, are no mere exercise in sentimental cinephilia or empty pastiche. What distinguishes Maddin’s compulsive returns to the era of German Expressionism is the desire to both archive and awaken the past. Careful (1992), Maddin’s mountain film, reanimates an anachronistic genre in order to craft an elegant allegory about the apprehensions and anxieties of everyday social and political life. My Winnipeg (2006) rescores the city symphony to reveal how personal history and cultural memory combine to structure the experience of the modern metropolis, whether it is Weimar Berlin or wintry Winnipeg. In this paper, I explore the influence of German Expressionism on Maddin’s work as well as argue that Maddin’s films preserve and perpetuate the energies and idiosyncrasies of Weimar cinema. Keywords: Guy Maddin, Canadian film, German Expressionism, Weimar cinema, cinephilia. Any effort to catalogue completely the references to, and reanimations of, German Expressionist cinema in the films of Guy Maddin would be a difficult, if not impossible, task. From his earliest work to his most recent, Maddin’s films are suffused with images and iconography drawn from the German films of the 1920s.