The Sociolinguistic Situation of the Kryz in Azerbaijan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Global Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition

Global Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition doi: 10.39127/GJFSN:1000104 Research Article Aliev Z.H. Gl J Food Sci Nutri: GJFSN-104. The Research of The Radial Growth of The Flora Species Which Do Not Have Special Protection on The South Hillsides of Greater Caucasus Prof. Dr. Aliyev Zakir Huseyn Oglu Institute of Soil Science and Agrochemistry of the National Academy of Sciences of Azerbaijan *Corresponding author: Prof. Dr. Aliyev Zakir Huseyn Oglu, Senior Scientific Officer, Erosion and Irrigation Institute of the National Academy of Sciences of the Azerbaijan Republic 1007AZ. Baku city, M. Kashgay house 36, Russia. Tel: +7994 (012) 440-42-67; Email: [email protected] Citation: Aliev Z.H (2020) The Research of The Radial Growth of The Flora Species Which Do Not Have Special Protection on The South Hillsides of Greater Caucasus. Gl J Foo Sci Nutri: GJFSN:104. Received Date: 24 January, 2020; Accepted Date: 30 January, 2020; Published Date: 05 February, 2020. Abstract The radial growth of the trunks of the following flora species which do not have special protection on the south hillsides of Greater Caucasus were studied in the article: Georgioan oak- Quercus iberica M. Bieb Common hornbeam - Caprinus betulus L. Common chestnut - Castanea sativa Mill. Black walnut - Juglans nigra L., Heart leaved alder - Alnus subcordata C.A. Mey. During the dendrochronological analyses, the dynamics of growth over the years were analysed based on the distances between the tree rings. The impact of the climatic factors to the growth of the trees was analysed and the ages of tree species were investigated. -

Təbiəti Qoruyaq! Let’S Protect the Nature!

Hesabat / Report 2013 1 Təbiəti qoruyaq! Let’s protect the nature! Hesabat / Report 2013 Hesabat Report Mündəricat Content Müşahidə Şurası Sədrinin müraciəti / Statement of Supervisory Board Chairman 05 Təməl informasiya / Key information 10 Strategiya və brend quruculuğu / Principles of Corporate Strategy 13 Təşkilatlarda üzvlük / Membership in organizations 16 İdarəetmə sistemi / Management system 20 Korporativ sistem/ Corporate system 21 Təşkilati struktur / Organizational structure 24 Strateji və operativ menecment / Team: strategic and operational management 28 Xarici mühit / Environment 34 Makroiqtisadi vəziyyət / Macroeconomics 35 Bank sistemi / Banking sistem 38 Maliyyə göstəriciləri / Financial Indexes 51 Aktivlər / Assets 52 Aktivlərin dinamikası / Assets breakdown 53 Öhdəliklər / Liabilities 55 Öhdəliklərin strukturu / Liability structure 56 Kapital / Capital 57 Kredit portfeli / Loan portfolio 59 Sektorlar üzrə təhlil / Breakdown by sectors 60 Fiziki şəxslərə verilmiş kreditlər / Loans to individuals 61 Fiziki şəxslərə verilmiş kreditlərin strukturu / Structure of loans to individuals 62 Müştəri hesabları / Customer accounts 63 Gəlirlər / Income 65 Xərclər / Expenses 69 Məhsul və xidmətlər / Products and services 73 Biznes kreditləri / Loans 74 Fiziki şəxslərin kreditləşməsi / Loans to individuals 75 Vəsaitlərin cəlb olunması / Funds Raising 77 Plastik kartlar və pul köçürmə sistemləri / Plastic Cards and Money Transfer 79 FOREX 82 Filiallar / Branches 87 Fəaliyyət şəbəkəsi / Branch network 88 Filialların və şöbələrin siyahısı -

Span Style="Color: Rgb(128, 0, 0);"

WithinWithin the the framework framework of of these these events, events, the the zonal zonal wrestling wrestling competition, competition, held held at at Hovsan Hovsan Olympic Olympic SportsSports Complex, Complex, among among schoolchildren schoolchildren has has ended. ended. In In the the competition, competition, the the athletes athletes competed competed in in 10 10 weight categories in freestyle and Greco-Roman wrestling. 130 athletes from 13 districts of Baku joined thethe fight fight for for the the title title of of winner. winner. According According to to the the results results of of the the competition, competition, the the teams teams of of Narimanov, Narimanov, Nasimi and Khazar districts won 1st, 2nd and 3rd places respectively in team score. TheThe zonal zonal athletics athletics competition competition was was organized organized in Ismayilli in Ismayilli district. district. The Theteams teams of Balakan, of Balakan, Zagatala,Zagatala, Gakh, Gakh, Gabala, Gabala, Oguz, Oguz, Ismayilli, Ismayilli, Shamakhi Shamakhi and and Goychay Goychay regions regions competed competed in in the the competition, competition, heldheld at at Ismayilli Ismayilli Olympic Olympic Sports Sports Complex. Complex. The The teams teams of of Oguz, Oguz, Ismayilli Ismayilli and and Gabala Gabala districts districts won won 1st, 1st, 2nd 2nd and 3rd places respectively. TheThe zonal zonal volleyball volleyball competition competition was was held held in in Oguz Oguz district. district. The The teams teams of of Balakan, Balakan, Oguz Oguz and and Sheki Sheki districtsdistricts won won 1st, 1st, 2nd 2nd and and 3rd 3rd places places respectively respectively in thein the zonal zonal competition, competition, held held at atOlympic Olympic Sports Sports Complex. -

WONDERLAND 2019 Ismayilli

INTERNATIONAL CAMP OF AZERBAIJAN - "WONDERLAND 2019 Ismayilli" Dear Scouts! The Association of Scouts of Azerbaijan invites you to take part in an international scout camp “Wonderland Azerbaijan 2019” which will be held in Ismailli, 1 July - 8 July in 2019. Brief Information: The very first international scout camp, Wonderland was held in Shaki in 2013 which was supported by The Ministry of Youth and Sports of the Azerbaijan Republic. Since then Wonderland has become an annual international scout camp. Next scout camp was held in South part of Azerbaijan in - Lerik, in 2014 where 208 scouts from all regions attended. In 2015 we pitched our tents in the West part of Azerbaijan – in Gadabay. Gadabay is another beautiful region of Azerbaijan. In 2016 the Wonderland was organized in Ganja in the European Youth Capital. Then we decided to organize the camp in Gabala in 2017. And the last camp was held in Nabran in 2018 where 500 scouts attended. This year we have decided to organize the scout camp in Ismayilli. So we decided to set up our tents in that marvelous city. Ismayilli is an ancient city of Azerbaijan. It is a town and capital of the Ismayilli District of Azerbaijan. Population 14,435 (2008). The territory of the district was part of the Albanian state, which was formed in the late 4th century and early 3rd century BC, long before it was erected. Historical facts prove that Mehranis, who belonged to Javanshir, had created Girdiman's prince in Ismayilli territory. Javanshir was of this generation. There is a fortress called Javanshir on the coast of Akchay, 4 km north of the village of Talantan. -

Title of the Paper

Nabiyev et al.: Formation characteristics of the mudflow process in Azerbaijan and the division into districts of territory based on risk level (on the example of the Greater Caucasus) - 5275 - FORMATION CHARACTERISTICS OF THE MUDFLOW PROCESS IN AZERBAIJAN AND THE DIVISION INTO DISTRICTS OF TERRITORY BASED ON RISK LEVEL (ON THE EXAMPLE OF THE GREATER CAUCASUS) NABIYEV, G. – TARIKHAZER, S.* – KULIYEVA, S. – MARDANOV, I. – ALIYEVA, S. Institute of Geography Named After Acad. H. Aliyev, Azerbaijan National Academy of Sciences 115, av. H. Cavid, Baku, Azerbaijan (phone: +994-50-386-8667; fax: +994-12-539-6966) *Corresponding author e-mail: [email protected] (Received 25th Jan 2019; accepted 6th Mar 2019) Abstract. In Azerbaijani part of the Greater Caucasus, which has been intensively developed in recent years in order to exploit recreational resources. Based on the interpretation of the ASP within the Azerbaijani part of the Greater Caucasus based on the derived from the effect of mudflow processes (the amount of material taken out, the erosive effect of the flow on the valley, the accounting of the mudflows and the basin as a whole, and the prevailing types and classes of mudflows, the geomorphological conditions of formation and passage mudflows, and statistical data on past mudflows) on the actual and possible damage affecting the population from mudflows a map-scheme was drawn up according to five- point scale. On the scale there are zones with a high (once in two-three years, one strong mudflow is possible) - V, with an average (possibility for one strong mudflow every three-five years) - IV, with a weak (every five-ten years is possible 1 strong mudflow) - III, with potential mudflow hazard - II and where no mudflow processes are observed - I. -

Administrative Territorial Divisions in Different Historical Periods

Administrative Department of the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan P R E S I D E N T I A L L I B R A R Y TERRITORIAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE UNITS C O N T E N T I. GENERAL INFORMATION ................................................................................................................. 3 II. BAKU ....................................................................................................................................................... 4 1. General background of Baku ............................................................................................................................ 5 2. History of the city of Baku ................................................................................................................................. 7 3. Museums ........................................................................................................................................................... 16 4. Historical Monuments ...................................................................................................................................... 20 The Maiden Tower ............................................................................................................................................ 20 The Shirvanshahs’ Palace ensemble ................................................................................................................ 22 The Sabael Castle ............................................................................................................................................. -

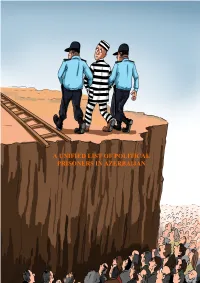

A Unified List of Political Prisoners in Azerbaijan

A UNIFIED LIST OF POLITICAL PRISONERS IN AZERBAIJAN A UNIFIED LIST OF POLITICAL PRISONERS IN AZERBAIJAN Covering the period up to 25 November 2019 Contents INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................... 3 THE DEFINITION OF POLITICAL PRISONERS ...................................................... 4 POLITICAL PRISONERS ............................................................................................ 5 A. JOURNALISTS AND BLOGGERS .................................................................... 5 B. POLITICAL AND SOCIAL ACTIVISTS .......................................................... 13 A case of financing of the opposition party ......................................................... 19 C. RELIGIOUS ACTIVISTS .................................................................................. 24 (1) Members of Muslim Unity Movement and people arrested in Nardaran Settlement ............................................................................................................ 24 (2) Chairman of Islamic Party of Azerbaijan and persons arrested together with him ....................................................................................................................... 51 (3) Other religious activists .................................................................................. 56 D. LIFETIME PRISONERS ................................................................................... 59 E. POLITICAL HOSTAGES ................................................................................ -

List of Political Prisoners

LIST OF POLITICAL PRISONERS Union for the Freedom for Political Prisoners of Azerbaijan on 10 August 2020 191 persons After former KGB general Heydar Aliyev came to power in 1993, in Azerbaijan, political repressions began in the country. In 2003, he was replaced by his son Ilham Aliyev, and the repressions against dissidents became systematic. Azerbaijani human rights defenders regularly compile the list of “prisoners of conscience” and political prisoners. Current list, by August 10, 2020, includes all arrested and convicted on political motives, about whom it was possible to collect detailed information. This list consists of 9 groups and includes 191 people: Group № 1 Journalists and Bloggers – 7 persons Group № 2 Members of Opposition Parties and Movements – 11 persons Group № 3 Arrested after the rally on July 14-15, 2020 – 36 persons Group № 4 Victims of Crimes in the MNS – 1 person Group № 5 Peaceful Believers – 51 persons Group № 6 Hostages - 1 person Group № 7 Convicted in Tartar case - 25 persons Group № 8 Convicted in Ganja case - 45 persons Group № 9 Life Term Sentenced – 14 persons Above the list of authors: Leyla Yunus (former "prisoner of conscience"), Director of the Institute for Peace and Democracy E-mail: [email protected] Skype: arif.yunusov1 Tel.: +31 611 43 59 90 Elshan Hasanov (former "prisoner of conscience"), Head of the Public Union "Center for Monitoring Political Prisoners" E-mail: [email protected] Tel.: +99 4556109144 Work method: Given list is compiled in accordance with a norm that defines the concept of “political prisoner” expounded in corresponding Resolution # 1900, adopted at the Parliamentary Assembly Session of the Council of Europe (PACE) in October 2012. -

The State of Armenian Historical Monuments In

THE STATE OF ARMENIAN HISTORICAL MONUMENTS IN AZERBAIJAN AND ARTSAKH THIS CURRENT RESEARCH HAS BEEN CARRIED OUT BY THE RESEARCH ON ARMENIAN ARCHITECTURE (RAA) FOUNDATION, YEREVAN, ARMENIA Author-Compiler Samvel Karapetian Translator and editor of the English text Gayane Movsissian Computer Design Armen Gevorgian ISBN 978-9939-843-00-1 © 2011, Research on Armenian Architecture (RAA) Foundation, Yerevan, Armenia THE STATE OF ARMENIAN HISTORICAL the Armenian heritage in its territory. MONUMENTS IN AZERBAIJAN AND ARTSAKH The year 1918 marked the foundation of the Republic of Azerbaijan, which came into being as a result of a diplomatic INTRODUCTION victory won by, and through the strenuous efforts of, its “godfa- ther,” i.e. Turkey. A large part of the newly-established state The Armenian Highland, which has been inhabited by comprised the territory of Historical Armenia, the rest of it Armenians since time immemorial, and which used to be home extending within the borders of the historical land of Caucasian to the kingdoms of Metz Hayk (Armenia Major) and Pokr Hayk Albania boasting an abundance of Armenian cultural monu- (Armenia Minor), abounds in a wide variety of centuries-old his- ments. In 1920 the Bolsheviks ratified the existence of this state, torical monuments created by its natives. the authorities of which showed a biased—if not hostile—atti- The present-day Republic of Armenia covers over 10 %— tude towards the Armenian historical monuments which had thus about 14 % together with the Republic of Artsakh (Nagorno- appeared within their rule from the very first years of their com- Karabakh)—of the vast territory of the Armenian Highland or ing to power. -

Studies Prepared Under the Project “Promoting Green Economy in GUAM Countries: Promotion of Renewable Energy Sources”

Studies prepared under the project “Promoting Green Economy in GUAM Countries: Promotion of Renewable Energy Sources” Azerbaijan, Georgia, Moldova, Ukraine February 2014 The project was implemented with the support of the Government of Japan through the Japan Special Fund (JSF), managed by the Regional Environmental Center for Central and Eastern Europe. Introduction The project “Promoting Green Economy in GUAM Countries: Promotion of Renewable Energy Sources” is supported by the Government of Japan through the Japan Special Fund (JSF) managed by the Regional Environmental Center for Central and Eastern Europe (REC). The JSF programme focuses on building capacities in the countries of Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) and beyond to develop climate policy and to support the implementation of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). The project targets Georgia, Ukraine, Azerbaijan and Moldova, focusing on how to increase the share of renewable energy sources (RES) at national level. Information for this analysis of the RES situation in the GUAM countries was gathered at a seminar held in cooperation with the GUAM Secretariat in Kiev on October 17–18, 2013, by representatives of the GUAM countries. Further information was subsequently obtained via desk research. The country studies describe the general situation and role of RES, including the institutional context; relevant national policies and legislation; the current share of RES in energy production; the technical possibilities for its enhancement; fiscal initiatives; RES potential in terms of biomass, solar, wind and hydro; and RES-related projections and targets. At the end of each study, gaps are identified and recommendations made for further action. -

Eastern Partnership Enhancing Judicial Reform in the Eastern Partnership Countries

Eastern Partnership Enhancing Judicial Reform in the Eastern Partnership Countries Efficient Judicial Systems Report 2014 Directorate General of Human Rights and Rule of Law Strasbourg, December 2014 1 The Efficient Judicial Systems 2014 report has been prepared by: Mr Adiz Hodzic, Member of the Working Group on Evaluation of Judicial systems of the European Commission for the Efficiency of Justice (CEPEJ) Mr Frans van der Doelen, Programme Manager of the Department of the Justice System, Ministry of Security and Justice, The Netherlands, Member of the Working Group on Evaluation of Judicial systems of the CEPEJ Mr Georg Stawa, Head of the Department for Projects, Strategy and Innovation, Federal Ministry of Justice, Austria, Chair of the CEPEJ 2 Table of content Conclusions and recommendations 3 Part I: Comparing Judicial Systems: Performance, Budget and Management Chapter 1: Introduction 11 Chapter 2: Disposition time and quality 17 Chapter 3: Public budget 26 Chapter 4: Management 35 Chapter 5: Efficiency: comparing resources, workload and performance (28 indicators) 44 Armenia 46 Azerbaijan 49 Georgia 51 Republic of Moldova 55 Ukraine 58 Chapter 6: Effectiveness: scoring on international indexes on the rule of law 64 Part II: Comparing Courts: Caseflow, Productivity and Efficiency 68 Armenia 74 Azerbaijan 90 Georgia 119 Republic of Moldova 139 Ukraine 158 Part III: Policy Making Capacities 178 Annexes 185 3 Conclusions and recommendations 1. Introduction This report focuses on efficiency of courts and the judicial systems of Azerbaijan, Armenia, Georgia, the Republic of Moldova and Ukraine, commonly referred the Easter Partnership Countries (EPCs) after the Eastern Partnership Programme of the European Union. -

Report Submitted by the Authorities of Azerbaijan on Measures Taken To

Committee of the Parties to the Council of Europe Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings CP(2019)01 Report submitted by the authorities of Azerbaijan on measures taken to comply with Committee of the Parties Recommendation CP(2018)24 on the implementation of the Council of Europe Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings Second evaluation round Received on 9 November 2019 Ce document n’est disponible qu’en anglais. Secretariat of the Council of Europe Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings 2 CP(2019)01 _______________________________________________________________________________________________________ - Develop a comprehensive statistical system on trafficking in human beings by compiling reliable statistical data on presumed and formally identified victims of THB from all main actors, including specialised NGOs and international organisations, as well as on the investigation, prosecution and adjudication of human trafficking cases, allowing disaggregation concerning sex, age, type of exploitation, and country of origin and/or destination. This should be accompanied by all the necessary measures to respect the right of data subjects to personal data protection, including when NGOs working with victims of trafficking are asked to provide information for the national database Response: Under the Law of the Republic of Azerbaijan “On Combating Trafficking in Human Beings”, a special police unit (Main Department on Combating Trafficking in Human Beings at the Ministry of Internal Affairs) was established on August 01, 2016 in order to effectively execute the tasks indicated in the National Action Plan, ensure the security of THB victims, provide them with professional aid, summarize and store THB related information in a single centre and to ensure that anti-trafficking measures are carried out by experienced and specially trained police officers and specially equipped police units.