2. History and Performace Practice of Adishakti

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Synonym to Conservation of Intangible Cultural Heritage: Folkland, International Centre for Folklore and Culture, Heading for Its 30Th Anniversary

A Synonym to Conservation of Intangible Cultural Heritage: Folkland, International Centre for Folklore and Culture, Heading for Its 30th Anniversary V. Jayarajan Folkland, International Centre for Folklore and Culture Folkland, International Centre for Folklore and Culture is an institution that was first registered on December 20, 1989 under the Societies Registration Act of 1860, vide No. 406/89. Over the last 16 years, it has passed through various stages of growth, especially in the fields of performance, production, documentation, and research, besides the preservation of folk art and culture. Since its inception in 1989, Folkland has passed through various phases of growth into a cultural organization with a global presence. As stated above, Folkland has delved deep into the fields of stage performance, production, documentation, and research, besides the preservation of folk art and culture. It has strived hard and treads the untrodden path with a clear motto of preservation and inculcation of old folk and cultural values in our society. Folkland has a veritable collection of folk songs, folk art forms, riddles, fables, myths, etc. that are on the verge of extinction. This collection has been recorded and archived well for scholastic endeavors and posterity. As such, Folkland defines itself as follows: 1. An international center for folklore and culture. 2. A cultural organization with clearly defined objectives and targets for research and the promotion of folk arts. Folkland has branched out and reached far and wide into almost every nook and corner of the world. The center has been credited with organizing many a festival on folk arts or workshop on folklore, culture, linguistics, etc. -

Particulars of Some Temples of Kerala Contents Particulars of Some

Particulars of some temples of Kerala Contents Particulars of some temples of Kerala .............................................. 1 Introduction ............................................................................................... 9 Temples of Kerala ................................................................................. 10 Temples of Kerala- an over view .................................................... 16 1. Achan Koil Dharma Sastha ...................................................... 23 2. Alathiyur Perumthiri(Hanuman) koil ................................. 24 3. Randu Moorthi temple of Alathur......................................... 27 4. Ambalappuzha Krishnan temple ........................................... 28 5. Amedha Saptha Mathruka Temple ....................................... 31 6. Ananteswar temple of Manjeswar ........................................ 35 7. Anchumana temple , Padivattam, Edapalli....................... 36 8. Aranmula Parthasarathy Temple ......................................... 38 9. Arathil Bhagawathi temple ..................................................... 41 10. Arpuda Narayana temple, Thirukodithaanam ................. 45 11. Aryankavu Dharma Sastha ...................................................... 47 12. Athingal Bhairavi temple ......................................................... 48 13. Attukkal BHagawathy Kshethram, Trivandrum ............. 50 14. Ayilur Akhileswaran (Shiva) and Sri Krishna temples ........................................................................................................... -

Hinduism: a Unit for Junior High and Middle School Social Studies Classes

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 322 075 SO 030 122 AUTHOR Galloway, Louis J. TITLE Hinduism: A Unit for Junior High and Middle School Social Studies Classes. SPONS AGENCY Center for International Education (ED), Washington, DC.; United States Educational Fouldation in India. PUB DATE 89 NOTE 12p. PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom Use - Guides (For Teachers) (052) EDRS PRICE mFol/rcol Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Area Studies; *Asian History; Class Activities; Curriculum Design; Epics; Foreign Countries; Foreign Culture; Global Approach; *History Instruction; Instructional Materials; Junior High Schools; *Non Western Civilization; Social Studies; Visual Aids IDENTIFIERS *Hinduism; *India ABSTRACT As an introduction and explanation of the historical development, major concepts, beliefs, practices, and traditions of Hinduism, this teaching unit provides a course outline for class discussion and activities for reading the classic epic, "The Ramayana." The unit requires 10 class sE,sions and utilizes slides, historical readings, class discussions, and filmstrips. Worksheets accompany the reading of this epic which serves as an introduction to Hinduism and some of its major concepts including: (1) karma; (2) dharma; and (3) reincarnation. (NL) ************************************************************t********** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can Le made * * from the original document. * *********************************************************************** rso Hinduism: A Unit For Junior High and Middle School Social Studies Classes t prepared by Louis J. Galloway CYZ Ladue Junior High School C=1 9701 Conway. Road St. Louis, Mo. 63124 as member of Summer Fulbright Seminar To India, 1988 sponsored by The United States Department of Education and The United States Educational Foundation in India U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Office of Educational Research and Improvement EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC) his document has been reproduced as received from the person or organization originating it. -

Location Accessibility Contact

Panchayat/ Municipality/ Parakkadavu Panchayat Corporation LOCATION District Ernakulam Nearest Town/ Royal Motors – 700 m Landmark/ Junction Nearest Bus statio Moozhikulam Bus Stop – 750 m Nearest Railway Angamaly Railway Station – 9.8 Km statio Aluva Railway Station – 15.2 Km ACCESSIBILITY Nearest Airport Cochin International Airport – 12 Km Nepathya Centre for Excellence in Koodiyattam Nepathya Koothambalam Moozhikulam-Ambalamuri Road Kurumassery, Aluva Ernakulam – 683579 CONTACT Phone 1: +91-9447209421 Phone 2: +91-7034243436 Email: [email protected] DATES FREQUENCY DURATION TIME April – May (to be advised) Annual 4-5 Days ABOUT THE FESTIVAL (Legend/History/Myth) Gurusmarana is a popular Koodiyattam Festival organized in memory of late Moozhikkulam Kochukuttan Chakyar by the Nepathya Centre for Excellence in Koodiyattam. Also known as the Moozhikulam Kochukuttan Chakyar Koodiyattam Festival, the event is a tribute to the Koodiyattam maestro. A prodigy who performed the entire Ramayana Prabandha within 123 days, he was instrumental in staging the complete version of ‘Ashcharyachoodamani’. He developed a distinctive style of presenting Purusharthavarnam and Prabandhakoothu on a strong traditional foothold. Koodiyattam or Kuttiyattam is a classical theatrical art form indigenous to Kerala and conferred heritage status by UNESCO. International Above 1000 RELEVANCE- NO. OF PEOPLE (Local / National / International) PARTICIPATED EVENTS/PROGRAMS DESCRIPTION (How festival is celebrated) The Sanskrit theatrical art form is presented by eminent artists who have excelled in the classical representation of Memorial Talk mythical stories. Legendary tales associated with Hindu Padakam mythology are presented. Padakam, Nangiarkoothu, Nangiarkoothu Chakyarkoothu, Koodiyattam and Mizhavu Melam are held Chakyarkoothu as part of the Moozhikulam Kochukuttan Chakyar Koodiyattam Koodiyattam Festival. A commemorative talk is held on a Mizhavu Melam topic relevant to the art form. -

Yoga and the Five Prana Vayus CONTENTS

Breath of Life Yoga and the Five Prana Vayus CONTENTS Prana Vayu: 4 The Breath of Vitality Apana Vayu: 9 The Anchoring Breath Samana Vayu: 14 The Breath of Balance Udana Vayu: 19 The Breath of Ascent Vyana Vayu: 24 The Breath of Integration By Sandra Anderson Yoga International senior editor Sandra Anderson is co-author of Yoga: Mastering the Basics and has taught yoga and meditation for over 25 years. Photography: Kathryn LeSoine, Model: Sandra Anderson; Wardrobe: Top by Zobha; Pant by Prana © 2011 Himalayan International Institute of Yoga Science and Philosophy of the U.S.A. All rights reserved. Reproduction or use of editorial or pictorial content in any manner without written permission is prohibited. Introduction t its heart, hatha yoga is more than just flexibility or strength in postures; it is the management of prana, the vital life force that animates all levels of being. Prana enables the body to move and the mind to think. It is the intelligence that coordinates our senses, and the perceptible manifestation of our higher selves. By becoming more attentive to prana—and enhancing and directing its flow through the Apractices of hatha yoga—we can invigorate the body and mind, develop an expanded inner awareness, and open the door to higher states of consciousness. The yoga tradition describes five movements or functions of prana known as the vayus (literally “winds”)—prana vayu (not to be confused with the undivided master prana), apana vayu, samana vayu, udana vayu, and vyana vayu. These five vayus govern different areas of the body and different physical and subtle activities. -

Arts of Kerala - a Deeper Exploration of Our Classical Art Forms

Arts of Kerala - a deeper exploration of our classical art forms Culture, especially classical performing arts of Kerala, is the raison d’etre for Neelambari. The beautiful one of its kind Koothambalam that is central to the facility, its location in the cultural capital of Kerala surrounded by a rich tradition and legendary artistes, and the deep rooted passion of its promoters for the cultural treasure of Kerala all combine to make Neelambari the idea stopover for an enchanting acquaintance with the classical arts of Kerala. The arts of Kerala package is for the aesthetically inclined, who would like to scratch beneath the surface of the rich classical tradition of Kerala, and by extension India. Duration: 5 nights Number of pax: 10 - 16 Day 1 Check in to Neelambari. No specific activity is scheduled on this date. An introduction to the facility will be provided with emphasis to its traditional performance theater (Koothambalam) and series of murals done in classical Kerala style. Day 2 Koodiyattam: This Sanskrit theatre is one of the oldest extant art forms in the world and was recognized by UNESCO as an Intangible Heritage of Humanity. Despite its ancient roots, Koodiyattam is surprisingly contemporary in its approach to theater, sensibility to characters and gender parity. The area around Neelambari is a haven for this classical art form, with prestigious institutions and acclaimed artistes making it their base. We will get introduced to the art form in a three four process - we will start with a multimedia presentation that summarizes the genesis and sensibilities of the art form. -

The Heart of Kerala!

Welcome to the Heart of Kerala! http://www.neelambari.co.in w: +91 9400 525150 [email protected] f: http://www.facebook.com/NeelambariKerala Overview Neelambari is a luxurious resort on the banks of Karuvannur puzha (river). It is constructed in authentic Kerala style and evokes grandeur and tradition. The central building consists of a classical performance arena (Koothambalam) and a traditional courtyard (Nalukettu). The cottages are luxurious with their own private balconies, spacious and clean bathrooms and well appointed bedrooms (each unit has a space of more than 75 sqm). Neelambari is situated in a very serene atmosphere right on the bank of a river, in a quiet, verdant village in central Kerala. There are several natural and historical attractions in the vicinity. Despite its rural charm, the facility is well connected, being less than an hour drive from Cochin International Airport. It is also easily accessible by rail and road and the nearest city is Thrissur, just 13 kms away. The facility offers authentic Ayurveda treatment, Yoga lessons, nature and village tourism, kayak and traditional boat trips in the river as well as traditional cultural performances in its Koothambalam. http://www.neelambari.co.in w: +91 9400 525150 [email protected] f: http://www.facebook.com/NeelambariKerala Our location Neelambari is located in Arattupuzha, a serene little village in the outskirts of Thrissur City. Thrissur has a rightful claim as the cultural capital of Kerala for more reasons than one. A host of prestigious institutions that assiduously preserve and nurture the cultural traditions of Kerala such as the Kerala Sangeetha Nataka Academy, Kerala Sahitya Academy, Kerala Lalitha Kala Academy, Kerala Kalamandalam, Unnayi Warrier Kalanilayam are located in Thrissur. -

A Brief Mention of Agni in Brihatrayee

ISSN 2664-3987 (Print) & ISSN 2664-6722 (Online) South Asian Research Journal of Medical Sciences Abbreviated Key Title: South Asian Res J Med Sci | Volume-1 | Issue-1| Jun-Jul -2019 | Review Article A Brief Mention of Agni in Brihatrayee Dr. Chumi Bhatta1*, Dr. Khagen Basumatary2 1P.G Scholar, Department of Samhita and Siddhanta, Government Ayurvedic college, Jalukbari-14, Assam, India 2Professor and HOD, Department of Samhita and Siddhanta, Government Ayurvedic college, Jalukbari-14, Assam, India *Corresponding Author Dr. Chumi Bhatta Article History Received: 21.06.2019 Accepted: 12.07.2019 Published: 30.07.2019 Abstract: The primary aim and objective of Ayurveda is to maintain the health of healthy person and to eradicate the diseases of a diseased person is the secondary one. One whose dosa, agni, dhatu and malas are in balanced state and whose senses, mind and soul are functioning properly is a healthy individual. Agni maintains the physiology of this deha desha. In other words agni controls the state of biological equilibrium of dosha, dhatu and mala. The derangement of agni produces various diseases and it is the root cause of all diseases. In Ayurveda the term agni is used in the sense of digestion of food and metabolic products.Agni converts food in the form of energy, which is responsible for all the vital functions of our body. So it is necessary to know all the reference found in brihatrayee. Keywords: ayurveda, agni, dosha, dhatu, mala INTRODUCTION The Ayurvedic concept of agni is critically important to our overall health. Agni is the force of intelligence within each cell, each tissue and every system within the body. -

HINDU GODS and GODDESSES 1. BRAHMA the First Deity of The

HINDU GODS AND GODDESSES 1. BRAHMA The first deity of the Hindu trinity, Lord Brahma is considered to be the god of Creation, including the cosmos and all of its beings. Brahma also symbolizes the mind and intellect since he is the source of all knowledge necessary for the universe. Typically you’ll find Brahma depicted with four faces, which symbolize the completeness of his knowledge, as well as four hands that each represent an aspect of the human personality (mind, intellect, ego and consciousness). 2. VISHNU The second deity of the Hindu trinity, Vishnu is the Preserver (of life). He is believed to sustain life through his adherence to principle, order, righteousness and truth. He also encourages his devotees to show kindness and compassion to all creatures. Vishnu is typically depicted with four arms to represent his omnipotence and omnipresence. It is also common to see Vishnu seated upon a coiled snake, symbolizing the ability to remain at peace in the face of fear or worry. 3. SHIVA The final deity of the Hindu trinity is Shiva, also known as the Destroyer. He is said to protect his followers from greed, lust and anger, as well as the illusion and ignorance that stand in the way of divine enlightenment. However, he is also considered to be responsible for death, destroying in order to bring rebirth and new life. Shiva is often depicted with a serpent around his neck, which represents Kundalini, or life energy. 4. GANESHA One of the most prevalent and best-known deities is Ganesha, easily recognized by his elephant head. -

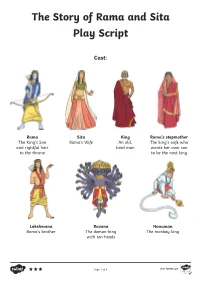

The Story of Rama and Sita Play Script

The Story of Rama and Sita Play Script Cast: Rama Sita King Rama’s stepmother The King’s Son Rama’s Wife An old, The king’s wife who and rightful heir tired man wants her own son to the throne to be the next king Lakshmana Ravana Hanuman Rama’s brother The demon-king The monkey king with ten heads Cast continued: Fawn Monkey Army Narrator 1 Monkey 1 Narrator 2 Monkey 2 Narrator 3 Monkey 3 Narrator 4 Monkey 4 Monkey 5 Prop Ideas: Character Masks Throne Cloak Gold Bracelets Walking Stick Bow and Arrow Diva Lamps (Health and Safety Note-candles should not be used) Audio Ideas: Bird Song Forest Animal Noises Lights up. The palace gardens. Rama and Sita enter the stage. They walk around, talking and laughing as the narrator speaks. Birds can be heard in the background. Once upon a time, there was a great warrior, Prince Rama, who had a beautiful Narrator 1: wife named Sita. Rama and Sita stop walking and stand in the middle of the stage. Sita: (looking up to the sky) What a beautiful day. Rama: (looking at Sita) Nothing compares to your beauty. Sita: (smiling) Come, let’s continue. Rama and Sita continue to walk around the stage, talking and laughing as the narrator continues. Rama was the eldest son of the king. He was a good man and popular with Narrator 1: the people of the land. He would become king one day, however his stepmother wanted her son to inherit the throne instead. Rama’s stepmother enters the stage. -

Harmony and Beauty in Ramayana 3

36 Summer Showers - 2002 3 Harmony and Beauty in Ramayana Daivadhinam jagat Sarvam Sathyadhinam tu Daivatam Tat Sathyam Uttamadhinam Uttamo Paradevata The entire creation is under the control of God. That God is under the control of Truth. That truth is under the control of noble ones. The noble people are greater than gods. (Sanskrit Verse) Embodiments of Love! HE society today is in utter need of Ramayana. We do not have children who re- Tspect their parents, nor do we have parents who have great affection for their children. We do not have disciples today who revere their preceptors; nor do we have preceptors who have great love for their 38 Summer Showers - 2002 Summer Showers - 2002 39 disciples. We do not have homes where parents shine as And moderately. role models for their children. We do not have homes Go to school where brothers live with mutual love and affection; nor And study diligently. do we have homes where wives and husbands shine as Earn a good name that ideals to others by virtue of their mutual love and You are an obedient student. affection. Good manners and courtesies have vanished. The Ramayana stands as an ideal for the trouble-torn Don’t move society of today in various fields of activities. When weather is damp. House is the First School And never go near ditches. Run and play The parents of today do not bother to find out the ways and means of bringing up their children and Have fun and frolic. keeping them under control. They think that their If you abide by responsibility is over after admitting them into a primary All the principles mentioned above school or a village school. -

Vishvarupadarsana Yoga (Vision of the Divine Cosmic Form)

Vishvarupadarsana Yoga (Vision of the Divine Cosmic form) 55 Verses Index S. No. Title Page No. 1. Introduction 1 2. Verse 1 5 3. Verse 2 15 4. Verse 3 19 5. Verse 4 22 6. Verse 6 28 7. Verse 7 31 8. Verse 8 33 9. Verse 9 34 10. Verse 10 36 11. Verse 11 40 12. Verse 12 42 13. Verse 13 43 14. Verse 14 45 15. Verse 15 47 16. Verse 16 50 17. Verse 17 53 18. Verse 18 58 19. Verse 19 68 S. No. Title Page No. 20. Verse 20 72 21. Verse 21 79 22. Verse 22 81 23. Verse 23 84 24. Verse 24 87 25. Verse 25 89 26. Verse 26 93 27. Verse 27 95 28. Verse 28 & 29 97 29. Verse 30 102 30. Verse 31 106 31. Verse 32 112 32. Verse 33 116 33. Verse 34 120 34. Verse 35 125 35. Verse 36 132 36. Verse 37 139 37. Verse 38 147 38. Verse 39 154 39. Verse 40 157 S. No. Title Page No. 40. Verse 41 161 41. Verse 42 168 42. Verse 43 175 43. Verse 44 184 44. Verse 45 187 45. Verse 46 190 46. Verse 47 192 47. Verse 48 196 48. Verse 49 200 49. Verse 50 204 50. Verse 51 206 51. Verse 52 208 52. Verse 53 210 53. Verse 54 212 54. Verse 55 216 CHAPTER - 11 Introduction : - All Vibhutis in form of Manifestations / Glories in world enumerated in Chapter 10. Previous Description : - Each object in creation taken up and Bagawan said, I am essence of that object means, Bagawan is in each of them… Bagawan is in everything.