Structures of the Glucocorticoid-Bound Adhesion Receptor GPR97–Go Complex

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sample Lab Report

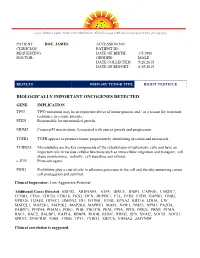

3030 Venture Lane, Suite 108 ● Melbourne, Florida 32934 ● Phone 321-253-5197 ● Fax 321-253-5199 PATIENT: DOE, JAMES ACCESSION NO: CLINICIAN/ PATIENT ID: REQUESTING DATE OF BIRTH: 1/5/1986 DOCTOR: GENDER: MALE DATE COLLECTED: 5/26/2015 DATE OF REPORT: 6/15/2015 RESULTS PRIMARY TUMOR TYPE RIGHT TESTICLE BIOLOGICALLY IMPORTANT ONCOGENES DETECTED GENE IMPLICATION TP53 TP53 mutations may be an important driver of tumorigenesis and / or a reason for treatment resistance in a some patients. PTEN Responsible for uncontrolled growth. MDM2 Causes p53 inactivation. Associated with cancer growth and progression. TGFB1 TGFB appears to promote tumor progession by stimulating invasion and metastasis. TUBB2A Microtubules are the key components of the cytoskeleton of eukaryotic cells and have an important role in various cellular functions such as intracellular migration and transport, cell shape maintenance, polarity, cell signaling and mitosis. c-JUN Proto-oncogene PHB2 Prohibitins play a crucial role in adhesion processes in the cell and thereby sustaining cancer cell propagation and survival. Clinical Impression: Low Aggressive Potential Additional Genes Detected: ABCG2, ARHGAP5, ATF4, BIRC5, BNIP3, CAPNS1, CARD17, CCNB1, CD24, CDC20, CDK18, CKS2, DCN, DEPDC1, FTL, FZD5, FZD9, GAPDH, GNB2, GPR126, H2AFZ, HDAC1, HMGN2, ID1, IFITM1, JUNB, KPNA2, KRT18, LDHA, LTF, MAD2L1, MAP2K1, MAP2K2, MAP2K4, MAPRE1, MAS1, NME1, NME3, NPM1, PA2G4, PABPC1, PFDN4, PGAM1, PGK1, PHB, PIK3CB, PKM, PPIA, PPIH, PRKX, PRNP, PTMA, RAC1, RAC2, RALBP1, RAP1A, RBBP4, RHOB, RHOC, -

Edinburgh Research Explorer

Edinburgh Research Explorer International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXXVIII. G protein-coupled receptor list Citation for published version: Davenport, AP, Alexander, SPH, Sharman, JL, Pawson, AJ, Benson, HE, Monaghan, AE, Liew, WC, Mpamhanga, CP, Bonner, TI, Neubig, RR, Pin, JP, Spedding, M & Harmar, AJ 2013, 'International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXXVIII. G protein-coupled receptor list: recommendations for new pairings with cognate ligands', Pharmacological reviews, vol. 65, no. 3, pp. 967-86. https://doi.org/10.1124/pr.112.007179 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1124/pr.112.007179 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: Pharmacological reviews Publisher Rights Statement: U.S. Government work not protected by U.S. copyright General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 02. Oct. 2021 1521-0081/65/3/967–986$25.00 http://dx.doi.org/10.1124/pr.112.007179 PHARMACOLOGICAL REVIEWS Pharmacol Rev 65:967–986, July 2013 U.S. -

G Protein-Coupled Receptors in Stem Cell Maintenance and Somatic Reprogramming to Pluripotent Or Cancer Stem Cells

BMB Reports - Manuscript Submission Manuscript Draft Manuscript Number: BMB-14-250 Title: G protein-coupled receptors in stem cell maintenance and somatic reprogramming to pluripotent or cancer stem cells Article Type: Mini Review Keywords: G protein-coupled receptors; stem cell maintenance; somatic reprogramming; cancer stem cells; pluripotent stem cell Corresponding Author: Ssang-Goo Cho Authors: Ssang-Goo Cho1,*, Hye Yeon Choi1, Subbroto Kumar Saha1, Kyeongseok Kim1, Sangsu Kim1, Gwang-Mo Yang1, BongWoo Kim1, Jin-hoi Kim1 Institution: 1Department of Animal Biotechnology, Animal Resources Research Center, and Incurable Disease Animal Model and Stem Cell Institute (IDASI), Konkuk University, 120 Neungdong-ro, Gwangjin-gu, Seoul 143-701, Republic of Korea, UNCORRECTED PROOF 1 G protein-coupled receptors in stem cell maintenance and somatic reprogramming to 2 pluripotent or cancer stem cells 3 4 Hye Yeon Choi, Subbroto Kumar Saha, Kyeongseok Kim, Sangsu Kim, Gwang-Mo 5 Yang, BongWoo Kim, Jin-hoi Kim, and Ssang-Goo Cho 6 7 Department of Animal Biotechnology, Animal Resources Research Center, and 8 Incurable Disease Animal Model and Stem Cell Institute (IDASI), Konkuk University, 9 120 Neungdong-ro, Gwangjin-gu, Seoul 143-701, Republic of Korea 10 * 11 Address correspondence to Ssang-Goo Cho, Department of Animal Biotechnology and 12 Animal Resources Research Center. Konkuk University, 120 Neungdong-ro, Gwangjin- 13 gu, Seoul 143-701, Republic of Korea. Tel: 82-2-450-4207, Fax: 82-2-450-1044, E-mail: 14 [email protected] 15 16 17 18 19 1 UNCORRECTED PROOF 20 Abstract 21 The G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) compose the third largest gene family in the 22 human genome, representing more than 800 distinct genes and 3–5% of the human genome. -

Eukaryotic Genome Annotation

Comparative Features of Multicellular Eukaryotic Genomes (2017) (First three statistics from www.ensembl.org; other from original papers) C. elegans A. thaliana D. melanogaster M. musculus H. sapiens Species name Nematode Thale Cress Fruit Fly Mouse Human Size (Mb) 103 136 143 3,482 3,555 # Protein-coding genes 20,362 27,655 13,918 22,598 20,338 (25,498 (13,601 original (30,000 (30,000 original est.) original est.) original est.) est.) Transcripts 58,941 55,157 34,749 131,195 200,310 Gene density (#/kb) 1/5 1/4.5 1/8.8 1/83 1/97 LINE/SINE (%) 0.4 0.5 0.7 27.4 33.6 LTR (%) 0.0 4.8 1.5 9.9 8.6 DNA Elements 5.3 5.1 0.7 0.9 3.1 Total repeats 6.5 10.5 3.1 38.6 46.4 Exons % genome size 27 28.8 24.0 per gene 4.0 5.4 4.1 8.4 8.7 average size (bp) 250 506 Introns % genome size 15.6 average size (bp) 168 Arabidopsis Chromosome Structures Sorghum Whole Genome Details Characterizing the Proteome The Protein World • Sequencing has defined o Many, many proteins • How can we use this data to: o Define genes in new genomes o Look for evolutionarily related genes o Follow evolution of genes ▪ Mixing of domains to create new proteins o Uncover important subsets of genes that ▪ That deep phylogenies • Plants vs. animals • Placental vs. non-placental animals • Monocots vs. dicots plants • Common nomenclature needed o Ensure consistency of interpretations InterPro (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/) Classification of Protein Families • Intergrated documentation resource for protein super families, families, domains and functional sites o Mitchell AL, Attwood TK, Babbitt PC, et al. -

Synaptamide Activates the Adhesion GPCR GPR110 (ADGRF1) Through GAIN Domain Binding

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-020-0831-6 OPEN Synaptamide activates the adhesion GPCR GPR110 (ADGRF1) through GAIN domain binding Bill X. Huang1, Xin Hu2, Heung-Sun Kwon1, Cheng Fu1, Ji-Won Lee1, Noel Southall2, Juan Marugan2 & ✉ Hee-Yong Kim1 1234567890():,; Adhesion G protein-coupled receptors (aGPCR) are characterized by a large extracellular region containing a conserved GPCR-autoproteolysis-inducing (GAIN) domain. Despite their relevance to several disease conditions, we do not understand the molecular mechanism by which aGPCRs are physiologically activated. GPR110 (ADGRF1) was recently deorphanized as the functional receptor of N-docosahexaenoylethanolamine (synaptamide), a potent synap- togenic metabolite of docosahexaenoic acid. Thus far, synaptamide is the first and only small- molecule endogenous ligand of an aGPCR. Here, we demonstrate the molecular basis of synaptamide-induced activation of GPR110 in living cells. Using in-cell chemical cross-linking/ mass spectrometry, computational modeling and mutagenesis-assisted functional assays, we discover that synaptamide specifically binds to the interface of GPR110 GAIN subdomains through interactions with residues Q511, N512 and Y513, causing an intracellular conforma- tional change near TM6 that triggers downstream signaling. This ligand-induced GAIN-tar- geted activation mechanism provides a framework for understanding the physiological function of aGPCRs and therapeutic targeting in the GAIN domain. 1 Laboratory of Molecular Signaling, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse -

The Adhesion G Protein-Coupled Receptor GPR56 Is a Cell-Autonomous Regulator of Oligodendrocyte Development

ARTICLE Received 27 May 2014 | Accepted 14 Dec 2014 | Published 21 Jan 2015 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms7121 OPEN The adhesion G protein-coupled receptor GPR56 is a cell-autonomous regulator of oligodendrocyte development Stefanie Giera1,*, Yiyu Deng1,*,w, Rong Luo1,*, Sarah D. Ackerman2, Amit Mogha2, Kelly R. Monk2,3, Yanqin Ying1, Sung-Jin Jeong1,w, Manabu Makinodan4,5, Allison R. Bialas4,5, Bernard S. Chang6, Beth Stevens4,5, Gabriel Corfas4,5,w & Xianhua Piao1 Mutations in GPR56, a member of the adhesion G protein-coupled receptor family, cause a human brain malformation called bilateral frontoparietal polymicrogyria (BFPP). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of BFPP brains reveals myelination defects in addition to brain malformation. However, the cellular role of GPR56 in oligodendrocyte development remains unknown. Here, we demonstrate that loss of Gpr56 leads to hypomyelination of the central nervous system in mice. GPR56 levels are abundant throughout early stages of oligodendrocyte development, but are downregulated in myelinating oligodendrocytes. Gpr56-knockout mice manifest with decreased oligodendrocyte precursor cell (OPC) proliferation and diminished levels of active RhoA, leading to fewer mature oligodendrocytes and a reduced number of myelinated axons in the corpus callosum and optic nerves. Conditional ablation of Gpr56 in OPCs leads to a reduced number of mature oligodendrocytes as seen in constitutive knockout of Gpr56. Together, our data define GPR56 as a cell-autonomous regulator of oligodendrocyte development. 1 Division of Newborn Medicine, Department of Medicine, Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts 02115, USA. 2 Department of Developmental Biology, Washington University School of Medicine, St Louis, Missouri 63110, USA. -

STACK: a Toolkit for Analysing Β-Helix Proteins

STACK: a toolkit for analysing ¯-helix proteins Master of Science Thesis (20 points) Salvatore Cappadona, Lars Diestelhorst Abstract ¯-helix proteins contain a solenoid fold consisting of repeated coils forming parallel ¯-sheets. Our goal is to formalise the intuitive notion of a ¯-helix in an objective algorithm. Our approach is based on first identifying residues stacks — linear spatial arrangements of residues with similar conformations — and then combining these elementary patterns to form ¯-coils and ¯-helices. Our algorithm has been implemented within STACK, a toolkit for analyzing ¯-helix proteins. STACK distinguishes aromatic, aliphatic and amidic stacks such as the asparagine ladder. Geometrical features are computed and stored in a relational database. These features include the axis of the ¯-helix, the stacks, the cross-sectional shape, the area of the coils and related packing information. An interface between STACK and a molecular visualisation program enables structural features to be highlighted automatically. i Contents 1 Introduction 1 2 Biological Background 2 2.1 Basic Concepts of Protein Structure ....................... 2 2.2 Secondary Structure ................................ 2 2.3 The ¯-Helix Fold .................................. 3 3 Parallel ¯-Helices 6 3.1 Introduction ..................................... 6 3.2 Nomenclature .................................... 6 3.2.1 Parallel ¯-Helix and its ¯-Sheets ..................... 6 3.2.2 Stacks ................................... 8 3.2.3 Coils ..................................... 8 3.2.4 The Core Region .............................. 8 3.3 Description of Known Structures ......................... 8 3.3.1 Helix Handedness .............................. 8 3.3.2 Right-Handed Parallel ¯-Helices ..................... 13 3.3.3 Left-Handed Parallel ¯-Helices ...................... 19 3.4 Amyloidosis .................................... 20 4 The STACK Toolkit 24 4.1 Identification of Structural Elements ....................... 24 4.1.1 Stacks ................................... -

1 Supplemental Material Maresin 1 Activates LGR6 Receptor

Supplemental Material Maresin 1 Activates LGR6 Receptor Promoting Phagocyte Immunoresolvent Functions Nan Chiang, Stephania Libreros, Paul C. Norris, Xavier de la Rosa, Charles N. Serhan Center for Experimental Therapeutics and Reperfusion Injury, Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative and Pain Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts 02115, USA. 1 Supplemental Table 1. Screening of orphan GPCRs with MaR1 Vehicle Vehicle MaR1 MaR1 mean RLU > GPCR ID SD % Activity Mean RLU Mean RLU + 2 SD Mean RLU Vehicle mean RLU+2 SD? ADMR 930920 33283 997486.5381 863760 -7% BAI1 172580 18362 209304.1828 176160 2% BAI2 26390 1354 29097.71737 26240 -1% BAI3 18040 758 19555.07976 18460 2% CCRL2 15090 402 15893.6583 13840 -8% CMKLR2 30080 1744 33568.954 28240 -6% DARC 119110 4817 128743.8016 126260 6% EBI2 101200 6004 113207.8197 105640 4% GHSR1B 3940 203 4345.298244 3700 -6% GPR101 41740 1593 44926.97349 41580 0% GPR103 21413 1484 24381.25067 23920 12% NO GPR107 366800 11007 388814.4922 360020 -2% GPR12 77980 1563 81105.4653 76260 -2% GPR123 1485190 46446 1578081.986 1342640 -10% GPR132 860940 17473 895885.901 826560 -4% GPR135 18720 1656 22032.6827 17540 -6% GPR137 40973 2285 45544.0809 39140 -4% GPR139 438280 16736 471751.0542 413120 -6% GPR141 30180 2080 34339.2307 29020 -4% GPR142 105250 12089 129427.069 101020 -4% GPR143 89390 5260 99910.40557 89380 0% GPR146 16860 551 17961.75617 16240 -4% GPR148 6160 484 7128.848113 7520 22% YES GPR149 50140 934 52008.76073 49720 -1% GPR15 10110 1086 12282.67884 -

Gpr126 Functions in Schwann Cells to Control Differentiation and Myelination Via G-Protein Activation Amit Mogha Washington University School of Medicine in St

Washington University School of Medicine Digital Commons@Becker Open Access Publications 11-2013 Gpr126 functions in schwann cells to control differentiation and myelination via G-protein activation Amit Mogha Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis Andrew E. Benesh Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis Chinmoy Patra Max Planck Institute for Heart and Lung Research Felix B. Engel University of Erlangen-Nurnberg Torsten Schoneberg University of Leipzig See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wustl.edu/open_access_pubs Recommended Citation Mogha, Amit; Benesh, Andrew E.; Patra, Chinmoy; Engel, Felix B.; Schoneberg, Torsten; Liebscher, Ines; and Monk, Kelly R., ,"Gpr126 functions in schwann cells to control differentiation and myelination via G-protein activation." The ourJ nal of Neuroscience.33,46. 17976-17985. (2013). https://digitalcommons.wustl.edu/open_access_pubs/1894 This Open Access Publication is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons@Becker. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Becker. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Amit Mogha, Andrew E. Benesh, Chinmoy Patra, Felix B. Engel, Torsten Schoneberg, Ines Liebscher, and Kelly R. Monk This open access publication is available at Digital Commons@Becker: https://digitalcommons.wustl.edu/open_access_pubs/1894 17976 • The Journal of Neuroscience, November 13, 2013 • 33(46):17976–17985 Development/Plasticity/Repair Gpr126 Functions in Schwann Cells to Control Differentiation and Myelination via G-Protein Activation Amit Mogha,1 Andrew E. Benesh,1 Chinmoy Patra,3 Felix B. Engel,3,4 Torsten Scho¨neberg,5 Ines Liebscher,5 and Kelly R. -

Calculating the Structure-Based Phylogenetic Relationship

CALCULATING THE STRUCTURE-BASED PHYLOGENETIC RELATIONSHIP OF DISTANTLY RELATED HOMOLOGOUS PROTEINS UTILIZING MAXIMUM LIKELIHOOD STRUCTURAL ALIGNMENT COMBINATORICS AND A NOVEL STRUCTURAL MOLECULAR CLOCK HYPOTHESIS A DISSERTATION IN Molecular Biology and Biochemistry and Cell Biology and Biophysics Presented to the Faculty of the University of Missouri-Kansas City in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy by SCOTT GARRETT FOY B.S., Southwest Baptist University, 2005 B.A., Truman State University, 2007 M.S., University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2009 Kansas City, Missouri 2013 © 2013 SCOTT GARRETT FOY ALL RIGHTS RESERVED CALCULATING THE STRUCTURE-BASED PHYLOGENETIC RELATIONSHIP OF DISTANTLY RELATED HOMOLOGOUS PROTEINS UTILIZING MAXIMUM LIKELIHOOD STRUCTURAL ALIGNMENT COMBINATORICS AND A NOVEL STRUCTURAL MOLECULAR CLOCK HYPOTHESIS Scott Garrett Foy, Candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2013 ABSTRACT Dendrograms establish the evolutionary relationships and homology of species, proteins, or genes. Homology modeling, ligand binding, and pharmaceutical testing all depend upon the homology ascertained by dendrograms. Regardless of the specific algorithm, all dendrograms that ascertain protein evolutionary homology are generated utilizing polypeptide sequences. However, because protein structures superiorly conserve homology and contain more biochemical information than their associated protein sequences, I hypothesize that utilizing the structure of a protein instead -

And Beta-Helical Protein Motifs

Soft Matter Mechanical Unfolding of Alpha- and Beta-helical Protein Motifs Journal: Soft Matter Manuscript ID SM-ART-10-2018-002046.R1 Article Type: Paper Date Submitted by the 28-Nov-2018 Author: Complete List of Authors: DeBenedictis, Elizabeth; Northwestern University Keten, Sinan; Northwestern University, Mechanical Engineering Page 1 of 10 Please doSoft not Matter adjust margins Soft Matter ARTICLE Mechanical Unfolding of Alpha- and Beta-helical Protein Motifs E. P. DeBenedictis and S. Keten* Received 24th September 2018, Alpha helices and beta sheets are the two most common secondary structure motifs in proteins. Beta-helical structures Accepted 00th January 20xx merge features of the two motifs, containing two or three beta-sheet faces connected by loops or turns in a single protein. Beta-helical structures form the basis of proteins with diverse mechanical functions such as bacterial adhesins, phage cell- DOI: 10.1039/x0xx00000x puncture devices, antifreeze proteins, and extracellular matrices. Alpha helices are commonly found in cellular and extracellular matrix components, whereas beta-helices such as curli fibrils are more common as bacterial and biofilm matrix www.rsc.org/ components. It is currently not known whether it may be advantageous to use one helical motif over the other for different structural and mechanical functions. To better understand the mechanical implications of using different helix motifs in networks, here we use Steered Molecular Dynamics (SMD) simulations to mechanically unfold multiple alpha- and beta- helical proteins at constant velocity at the single molecule scale. We focus on the energy dissipated during unfolding as a means of comparison between proteins and work normalized by protein characteristics (initial and final length, # H-bonds, # residues, etc.). -

Introduction to the Local Theory of Curves and Surfaces

Introduction to the Local Theory of Curves and Surfaces Notes of a course for the ICTP-CUI Master of Science in Mathematics Marco Abate, Fabrizio Bianchi (with thanks to Francesca Tovena) (Much more on this subject can be found in [1]) CHAPTER 1 Local theory of curves Elementary geometry gives a fairly accurate and well-established notion of what is a straight line, whereas is somewhat vague about curves in general. Intuitively, the difference between a straight line and a curve is that the former is, well, straight while the latter is curved. But is it possible to measure how curved a curve is, that is, how far it is from being straight? And what, exactly, is a curve? The main goal of this chapter is to answer these questions. After comparing in the first two sections advantages and disadvantages of several ways of giving a formal definition of a curve, in the third section we shall show how Differential Calculus enables us to accurately measure the curvature of a curve. For curves in space, we shall also measure the torsion of a curve, that is, how far a curve is from being contained in a plane, and we shall show how curvature and torsion completely describe a curve in space. 1.1. How to define a curve n What is a curve (in a plane, in space, in R )? Since we are in a mathematical course, rather than in a course about military history of Prussian light cavalry, the only acceptable answer to such a question is a precise definition, identifying exactly the objects that deserve being called curves and those that do not.