The Adhesion G Protein-Coupled Receptor GPR56 Is a Cell-Autonomous Regulator of Oligodendrocyte Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Killer-Like Receptors and GPR56 Progressive Expression Defines Cytokine Production of Human CD4+ Memory T Cells

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-10018-1 OPEN Killer-like receptors and GPR56 progressive expression defines cytokine production of human CD4+ memory T cells Kim-Long Truong1,7, Stephan Schlickeiser1,2,7, Katrin Vogt1, David Boës1, Katarina Stanko1, Christine Appelt1, Mathias Streitz1, Gerald Grütz1,2, Nadja Stobutzki1, Christian Meisel1, Christina Iwert1, Stefan Tomiuk3, Julia K. Polansky2,4, Andreas Pascher5, Nina Babel2,6, Ulrik Stervbo 6, Igor Sauer 5, Undine Gerlach5 & Birgit Sawitzki1,2 1234567890():,; All memory T cells mount an accelerated response on antigen reencounter, but significant functional heterogeneity is present within the respective memory T-cell subsets as defined by CCR7 and CD45RA expression, thereby warranting further stratification. Here we show that several surface markers, including KLRB1, KLRG1, GPR56, and KLRF1, help define low, high, or exhausted cytokine producers within human peripheral and intrahepatic CD4+ memory T-cell populations. Highest simultaneous production of TNF and IFN-γ is observed in KLRB1+KLRG1+GPR56+ CD4 T cells. By contrast, KLRF1 expression is associated with T-cell exhaustion and reduced TNF/IFN-γ production. Lastly, TCRβ repertoire analysis and in vitro differentiation support a regulated, progressive expression for these markers during CD4+ memory T-cell differentiation. Our results thus help refine the classification of human memory T cells to provide insights on inflammatory disease progression and immunotherapy development. 1 Institute of Medical Immunology, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Freie Universität Berlin, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin and Berlin Institute of Health, 13353 Berlin, Germany. 2 Berlin-Brandenburg Center for Regenerative Therapies (BCRT), Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, 13353 Berlin, Germany. 3 Milteny Biotec GmbH, 51429 Bergisch Gladbach, Germany. -

Distribution and Clinical Significance of Heparan Sulfate Proteoglycans in Ovarian Cancer

5178 Vol. 10, 5178–5186, August 1, 2004 Clinical Cancer Research Distribution and Clinical Significance of Heparan Sulfate Proteoglycans in Ovarian Cancer E. June Davies,1 Fiona H. Blackhall,1 decan-1 and glypican-1 were poor prognostic factors for Jonathan H. Shanks,2 Guido David,3 survival in univariate analysis. Alan T. McGown,4 Ric Swindell,5 Conclusion: We report for the first time distinct pat- 6 7 terns of expression of cell surface and extracellular matrix Richard J. Slade, Pierre Martin-Hirsch, heparan sulfate proteoglycans in normal ovary compared 1 1 John T. Gallagher, and Gordon C. Jayson with ovarian tumors. These data reinforce the role of the 1Cancer Research UK and University of Manchester Department of tumor stroma in ovarian adenocarcinoma and suggest that Medical Oncology, Paterson Institute for Cancer Research, stromal induction of syndecan-1 contributes to the patho- Manchester, England; 2Department of Histopathology, Christie Hospital NHS Trust, Manchester, England; 3Department of Medicine, genesis of this malignancy. University of Leuven, Leuven, Belgium.; 4Cancer Research UK Department of Experimental Pharmacology, Paterson Institute for Cancer Research, Manchester, England; 5Department of Medical INTRODUCTION Statistics, Christie Hospital NHS Trust, Manchester, England; The heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) play diverse 6Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Hope Hospital, Salford, Manchester, England; 7Department of Gynaecological Oncology, St. roles in tumor biology by mediating adhesion and migration -

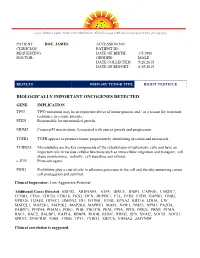

Sample Lab Report

3030 Venture Lane, Suite 108 ● Melbourne, Florida 32934 ● Phone 321-253-5197 ● Fax 321-253-5199 PATIENT: DOE, JAMES ACCESSION NO: CLINICIAN/ PATIENT ID: REQUESTING DATE OF BIRTH: 1/5/1986 DOCTOR: GENDER: MALE DATE COLLECTED: 5/26/2015 DATE OF REPORT: 6/15/2015 RESULTS PRIMARY TUMOR TYPE RIGHT TESTICLE BIOLOGICALLY IMPORTANT ONCOGENES DETECTED GENE IMPLICATION TP53 TP53 mutations may be an important driver of tumorigenesis and / or a reason for treatment resistance in a some patients. PTEN Responsible for uncontrolled growth. MDM2 Causes p53 inactivation. Associated with cancer growth and progression. TGFB1 TGFB appears to promote tumor progession by stimulating invasion and metastasis. TUBB2A Microtubules are the key components of the cytoskeleton of eukaryotic cells and have an important role in various cellular functions such as intracellular migration and transport, cell shape maintenance, polarity, cell signaling and mitosis. c-JUN Proto-oncogene PHB2 Prohibitins play a crucial role in adhesion processes in the cell and thereby sustaining cancer cell propagation and survival. Clinical Impression: Low Aggressive Potential Additional Genes Detected: ABCG2, ARHGAP5, ATF4, BIRC5, BNIP3, CAPNS1, CARD17, CCNB1, CD24, CDC20, CDK18, CKS2, DCN, DEPDC1, FTL, FZD5, FZD9, GAPDH, GNB2, GPR126, H2AFZ, HDAC1, HMGN2, ID1, IFITM1, JUNB, KPNA2, KRT18, LDHA, LTF, MAD2L1, MAP2K1, MAP2K2, MAP2K4, MAPRE1, MAS1, NME1, NME3, NPM1, PA2G4, PABPC1, PFDN4, PGAM1, PGK1, PHB, PIK3CB, PKM, PPIA, PPIH, PRKX, PRNP, PTMA, RAC1, RAC2, RALBP1, RAP1A, RBBP4, RHOB, RHOC, -

And MMP-Mediated Cell–Matrix Interactions in the Tumor Microenvironment

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review Hold on or Cut? Integrin- and MMP-Mediated Cell–Matrix Interactions in the Tumor Microenvironment Stephan Niland and Johannes A. Eble * Institute of Physiological Chemistry and Pathobiochemistry, University of Münster, 48149 Münster, Germany; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The tumor microenvironment (TME) has become the focus of interest in cancer research and treatment. It includes the extracellular matrix (ECM) and ECM-modifying enzymes that are secreted by cancer and neighboring cells. The ECM serves both to anchor the tumor cells embedded in it and as a means of communication between the various cellular and non-cellular components of the TME. The cells of the TME modify their surrounding cancer-characteristic ECM. This in turn provides feedback to them via cellular receptors, thereby regulating, together with cytokines and exosomes, differentiation processes as well as tumor progression and spread. Matrix remodeling is accomplished by altering the repertoire of ECM components and by biophysical changes in stiffness and tension caused by ECM-crosslinking and ECM-degrading enzymes, in particular matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs). These can degrade ECM barriers or, by partial proteolysis, release soluble ECM fragments called matrikines, which influence cells inside and outside the TME. This review examines the changes in the ECM of the TME and the interaction between cells and the ECM, with a particular focus on MMPs. Keywords: tumor microenvironment; extracellular matrix; integrins; matrix metalloproteinases; matrikines Citation: Niland, S.; Eble, J.A. Hold on or Cut? Integrin- and MMP-Mediated Cell–Matrix 1. Introduction Interactions in the Tumor Microenvironment. -

Edinburgh Research Explorer

Edinburgh Research Explorer International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXXVIII. G protein-coupled receptor list Citation for published version: Davenport, AP, Alexander, SPH, Sharman, JL, Pawson, AJ, Benson, HE, Monaghan, AE, Liew, WC, Mpamhanga, CP, Bonner, TI, Neubig, RR, Pin, JP, Spedding, M & Harmar, AJ 2013, 'International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXXVIII. G protein-coupled receptor list: recommendations for new pairings with cognate ligands', Pharmacological reviews, vol. 65, no. 3, pp. 967-86. https://doi.org/10.1124/pr.112.007179 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1124/pr.112.007179 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: Pharmacological reviews Publisher Rights Statement: U.S. Government work not protected by U.S. copyright General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 02. Oct. 2021 1521-0081/65/3/967–986$25.00 http://dx.doi.org/10.1124/pr.112.007179 PHARMACOLOGICAL REVIEWS Pharmacol Rev 65:967–986, July 2013 U.S. -

Protein Identities in Evs Isolated from U87-MG GBM Cells As Determined by NG LC-MS/MS

Protein identities in EVs isolated from U87-MG GBM cells as determined by NG LC-MS/MS. No. Accession Description Σ Coverage Σ# Proteins Σ# Unique Peptides Σ# Peptides Σ# PSMs # AAs MW [kDa] calc. pI 1 A8MS94 Putative golgin subfamily A member 2-like protein 5 OS=Homo sapiens PE=5 SV=2 - [GG2L5_HUMAN] 100 1 1 7 88 110 12,03704523 5,681152344 2 P60660 Myosin light polypeptide 6 OS=Homo sapiens GN=MYL6 PE=1 SV=2 - [MYL6_HUMAN] 100 3 5 17 173 151 16,91913397 4,652832031 3 Q6ZYL4 General transcription factor IIH subunit 5 OS=Homo sapiens GN=GTF2H5 PE=1 SV=1 - [TF2H5_HUMAN] 98,59 1 1 4 13 71 8,048185945 4,652832031 4 P60709 Actin, cytoplasmic 1 OS=Homo sapiens GN=ACTB PE=1 SV=1 - [ACTB_HUMAN] 97,6 5 5 35 917 375 41,70973209 5,478027344 5 P13489 Ribonuclease inhibitor OS=Homo sapiens GN=RNH1 PE=1 SV=2 - [RINI_HUMAN] 96,75 1 12 37 173 461 49,94108966 4,817871094 6 P09382 Galectin-1 OS=Homo sapiens GN=LGALS1 PE=1 SV=2 - [LEG1_HUMAN] 96,3 1 7 14 283 135 14,70620005 5,503417969 7 P60174 Triosephosphate isomerase OS=Homo sapiens GN=TPI1 PE=1 SV=3 - [TPIS_HUMAN] 95,1 3 16 25 375 286 30,77169764 5,922363281 8 P04406 Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase OS=Homo sapiens GN=GAPDH PE=1 SV=3 - [G3P_HUMAN] 94,63 2 13 31 509 335 36,03039959 8,455566406 9 Q15185 Prostaglandin E synthase 3 OS=Homo sapiens GN=PTGES3 PE=1 SV=1 - [TEBP_HUMAN] 93,13 1 5 12 74 160 18,68541938 4,538574219 10 P09417 Dihydropteridine reductase OS=Homo sapiens GN=QDPR PE=1 SV=2 - [DHPR_HUMAN] 93,03 1 1 17 69 244 25,77302971 7,371582031 11 P01911 HLA class II histocompatibility antigen, -

Biosynthesized Multivalent Lacritin Peptides Stimulate Exosome Production in Human Corneal Epithelium

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Article Biosynthesized Multivalent Lacritin Peptides Stimulate Exosome Production in Human Corneal Epithelium Changrim Lee 1, Maria C. Edman 2 , Gordon W. Laurie 3 , Sarah F. Hamm-Alvarez 1,2,* and J. Andrew MacKay 1,2,4,* 1 Department of Pharmacology and Pharmaceutical Sciences, School of Pharmacy, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90033, USA; [email protected] 2 Department of Ophthalmology, USC Roski Eye Institute and Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90033, USA; [email protected] 3 Department of Cell Biology, School of Medicine, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA 22908, USA; [email protected] 4 Department of Biomedical Engineering, Viterbi School of Engineering, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90089, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] (S.F.H.-A.); [email protected] (J.A.M.) Received: 30 July 2020; Accepted: 24 August 2020; Published: 26 August 2020 Abstract: Lacripep is a therapeutic peptide derived from the human tear protein, Lacritin. Lacripep interacts with syndecan-1 and induces mitogenesis upon the removal of heparan sulfates (HS) that are attached at the extracellular domain of syndecan-1. The presence of HS is a prerequisite for the syndecan-1 clustering that stimulates exosome biogenesis and release. Therefore, syndecan-1- mediated mitogenesis versus HS-mediated exosome biogenesis are assumed to be mutually exclusive. This study introduces a biosynthesized fusion between Lacripep and an elastin-like polypeptide named LP-A96, and evaluates its activity on cell motility enhancement versus exosome biogenesis. LP-A96 activates both downstream pathways in a dose-dependent manner. -

Progastrin Production Transitions from Bmi1+/Prox1+ to Lgr5high Cells During Early Intestinal Tumorigenesis Julie Giraud, M

Progastrin production transitions from Bmi1+/Prox1+ to Lgr5high cells during early intestinal tumorigenesis Julie Giraud, M. Foroutan, Jihane Boubaker-Vitre, Fanny Grillet, Z. Homayed, U. Jadhav, Philippe Crespy, Cyril Breuker, J-F. Bourgaux, J. Hazerbroucq, et al. To cite this version: Julie Giraud, M. Foroutan, Jihane Boubaker-Vitre, Fanny Grillet, Z. Homayed, et al.. Progastrin production transitions from Bmi1+/Prox1+ to Lgr5high cells during early intestinal tumorigene- sis. Translational Oncology, Elsevier, 2020, 14 (2), pp.101001. 10.1016/j.tranon.2020.101001. hal- 03090781 HAL Id: hal-03090781 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03090781 Submitted on 12 Jan 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License Translational Oncology 14 (2021) 101001 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Translational Oncology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/tranon Original Research + + high Progastrin production transitions from Bmi1 /Prox1 to Lgr5 cells during early intestinal tumorigenesis J. Giraud a, M. Foroutan b,c,1, J. Boubaker-Vitre a,1, F. Grillet a, Z. Homayed a, U. Jadhav d, P. Crespy a, C. Breuker a, J-F. -

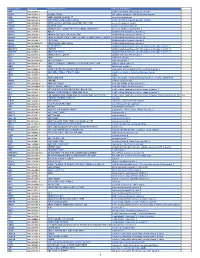

Pancancer Progression Human Vjune2017

Gene Symbol Accession Alias/Prev Symbol Official Full Name AAMP NM_001087.3 - angio-associated, migratory cell protein ABI3BP NM_015429.3 NESHBP|TARSH ABI family, member 3 (NESH) binding protein ACHE NM_000665.3 ACEE|ARACHE|N-ACHE|YT acetylcholinesterase ACTG2 NM_001615.3 ACT|ACTA3|ACTE|ACTL3|ACTSG actin, gamma 2, smooth muscle, enteric ACVR1 NM_001105.2 ACTRI|ACVR1A|ACVRLK2|ALK2|FOP|SKR1|TSRI activin A receptor, type I ACVR1C NM_145259.2 ACVRLK7|ALK7 activin A receptor, type IC ACVRL1 NM_000020.1 ACVRLK1|ALK-1|ALK1|HHT|HHT2|ORW2|SKR3|TSR-I activin A receptor type II-like 1 ADAM15 NM_207195.1 MDC15 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 15 ADAM17 NM_003183.4 ADAM18|CD156B|CSVP|NISBD|TACE ADAM metallopeptidase domain 17 ADAM28 NM_014265.4 ADAM 28|ADAM23|MDC-L|MDC-Lm|MDC-Ls|MDCL|eMDC II|eMDCII ADAM metallopeptidase domain 28 ADAM8 NM_001109.4 CD156|MS2 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 8 ADAM9 NM_001005845.1 CORD9|MCMP|MDC9|Mltng ADAM metallopeptidase domain 9 ADAMTS1 NM_006988.3 C3-C5|METH1 ADAM metallopeptidase with thrombospondin type 1 motif, 1 ADAMTS12 NM_030955.2 PRO4389 ADAM metallopeptidase with thrombospondin type 1 motif, 12 ADAMTS8 NM_007037.4 ADAM-TS8|METH2 ADAM metallopeptidase with thrombospondin type 1 motif, 8 ADAP1 NM_006869.2 CENTA1|GCS1L|p42IP4 ArfGAP with dual PH domains 1 ADD1 NM_001119.4 ADDA adducin 1 (alpha) ADM2 NM_001253845.1 AM2|dJ579N16.4 adrenomedullin 2 ADRA2B NM_000682.4 ADRA2L1|ADRA2RL1|ADRARL1|ALPHA2BAR|alpha-2BAR adrenoceptor alpha 2B AEBP1 NM_001129.3 ACLP AE binding protein 1 AGGF1 NM_018046.3 GPATC7|GPATCH7|HSU84971|HUS84971|VG5Q -

Analysis of Transport and Targeting of Syndecan-1: Effect of Cytoplasmic Tail Deletions Heini M

Molecular Biology of the Cell Vol. 5, 1325-1339, December 1994 Analysis of Transport and Targeting of Syndecan-1: Effect of Cytoplasmic Tail Deletions Heini M. Miettinen,*t# Susan N. Edwards,* and Markku Jalkanen* *Centre for Biotechnology, FIN-20521 Turku, Finland; and tDepartment of Medical Biochemistry, University of Turku, FIN-20520 Turku, Finland Submitted October 6, 1994; Accepted October 26, 1994 Monitoring Editor: Richard Hynes Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells and Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells were transfected with wild-type and cytoplasmic deletion mutants of mouse syndecan-1 to study the requirements for transport and polarized expression of this proteoglycan. Expression in MDCK cells revealed that wild-type syndecan-1 is directed to the basolateral surface via a brefeldin A-insensitive route. A deletion of the last 12 amino acids of the syndecan- 1 cytoplasmic tail (CT22) was sufficient to result in the appearance of mutant proteoglycans at both the basolateral and apical cell surfaces. Treatment with brefeldin A was able to prevent apical transport of the mutants. We thus propose that the C-terminal part of the cytoplasmic tail is required for steady-state basolateral distribution of syndecan-1. In CHO cells a deletion of the last 25 or 33 amino acids of the 34-residue cytoplasmic domain (CT9 and CT1, respectively) resulted in partial retention of the mutants in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). A deletion mutant lacking the last 12 amino acids (CT22) was not retained. Interestingly, the unglycosylated core proteins of the CT9 and CT1 mutants showed a significantly lower apparent molecular weight when analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis than wild-type syndecan- 1. -

GPR56 Regulates VEGF Production and Angiogenesis During Melanoma Progression

Published OnlineFirst July 1, 2011; DOI: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4543 Cancer Tumor and Stem Cell Biology Research GPR56 Regulates VEGF Production and Angiogenesis during Melanoma Progression Liquan Yang1, Guangchun Chen1, Sonali Mohanty1, Glynis Scott2, Fabeha Fazal3, Arshad Rahman3, Shahinoor Begum4, Richard O. Hynes4, and Lei Xu1,2 Abstract Angiogenesis is a critical step during cancer progression. The VEGF is a major stimulator for angiogenesis and is predominantly contributed by cancer cells in tumors. Inhibition of the VEGF signaling pathway has shown promising therapeutic benefits for cancer patients, but adaptive tumor responses are often observed, indicating the need for further understanding of VEGF regulation. We report that a novel G protein–coupled receptor, GPR56, inhibits VEGF production from the melanoma cell lines and impedes melanoma angiogen- esis and growth, through the serine threonine proline-rich segment in its N-terminus and a signaling pathway involving protein kinase Ca. We also present evidence that the two fragments of GPR56, which are generated by autocatalyzed cleavage, played distinct roles in regulating VEGF production and melanoma progression. Finally, consistent with its suppressive roles in melanoma progression, the expression levels of GPR56 are inversely correlated with the malignancy of melanomas in human subjects. We propose that components of the GPR56-mediated signaling pathway may serve as new targets for antiangiogenic treatment of melanoma. Cancer Res; 71(16); 1–11. Ó2011 AACR. Introduction its occurrence strongly argues for combinations of antiangio- genic regimens to effectively treat cancer. Angiogenesis is a process of nascent blood vessel formation VEGF is a potent growth factor for angiogenesis and is a (1) and is critical for tumor growth and metastasis (2). -

Synaptamide Activates the Adhesion GPCR GPR110 (ADGRF1) Through GAIN Domain Binding

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-020-0831-6 OPEN Synaptamide activates the adhesion GPCR GPR110 (ADGRF1) through GAIN domain binding Bill X. Huang1, Xin Hu2, Heung-Sun Kwon1, Cheng Fu1, Ji-Won Lee1, Noel Southall2, Juan Marugan2 & ✉ Hee-Yong Kim1 1234567890():,; Adhesion G protein-coupled receptors (aGPCR) are characterized by a large extracellular region containing a conserved GPCR-autoproteolysis-inducing (GAIN) domain. Despite their relevance to several disease conditions, we do not understand the molecular mechanism by which aGPCRs are physiologically activated. GPR110 (ADGRF1) was recently deorphanized as the functional receptor of N-docosahexaenoylethanolamine (synaptamide), a potent synap- togenic metabolite of docosahexaenoic acid. Thus far, synaptamide is the first and only small- molecule endogenous ligand of an aGPCR. Here, we demonstrate the molecular basis of synaptamide-induced activation of GPR110 in living cells. Using in-cell chemical cross-linking/ mass spectrometry, computational modeling and mutagenesis-assisted functional assays, we discover that synaptamide specifically binds to the interface of GPR110 GAIN subdomains through interactions with residues Q511, N512 and Y513, causing an intracellular conforma- tional change near TM6 that triggers downstream signaling. This ligand-induced GAIN-tar- geted activation mechanism provides a framework for understanding the physiological function of aGPCRs and therapeutic targeting in the GAIN domain. 1 Laboratory of Molecular Signaling, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse