Fraternity & Sorority Advisor Manual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BGSU Greek Report Data Spring 2018 Community Fall Totals/Averages

BGSU Greek Report Data Spring 2018 Community Fall Totals/Averages Total BGSU Undergraduate Men 5,883 Total BGSU Undergraduate Women 7,750 Total Undergraduate Students 13,633 Total Fraternity Men 694 Total Sorority Women 966 Total Greek Students 1,660 Percentage Greek Students 12.18% All Fraternity GPA 3.06 All Sorority GPA 3.36 All Greek GPA 3.21 All University Male GPA 3.17 All University Female GPA 3.41 All Undergraduate GPA 3.31 Total Philanthropy Dollars Raised $91,625 Total Community Service Hours 25,561 BGSU Greek Report Data - Interfraternity Council (IFC) # of New Total New Change in Money Donated Total Active Community Chapter Members Chapter Mem. semester to Members Sem. GPA Service Hrs Reported Sem. GPA Sem. GPA GPA Philanthropies Alpha Sigma Phi 56 7 2.94 2.98 2.66 -0.02 $2,034.39 640 Alpha Tau Omega 37 6 3.12 3.10 3.27 0.11 2.994.52 430 Delta Tau Delta 37 3 2.88 2.92 2.50 0.22 $400 370 Kappa Sigma 68 9 3.21 3.27 2.80 0.12 $8,149 3048 Lambda Chi Alpha 45 5 3.12 3.14 3.00 0.07 $352 410 Phi Delta Theta 26 4 3.03 3.04 2.95 0.00 $3,200 348 Phi Gamma Delta (FIJI) 66 7 2.97 2.99 2.88 0.01 $118 643 Phi Mu Alpha 39 7 3.33 3.35 3.23 0.07 $108 96 Pi Kappa Alpha 74 12 2.93 2.93 2.95 -0.12 $7,750 5659 Sigma Alpha Epsilon 24 2 3.09 3.02 3.79 0.05 $310 342 Sigma Chi 47 6 2.98 2.92 3.36 -0.14 $10,000 693 Sigma Nu 18 2 3.43 2.64 3.48 0.41 $2,126 256 Sigma Phi Epsilon 54 4 2.86 2.84 3.00 0.03 $4,250 600 Tau Kappa Epsilon 73 4 3.15 3.15 3.09 0.03 $10,976 1877 Theta Chi 7 3 2.74 2.94 2.94 -0.48 ** ** IFC Totals 671 81 $49,774 15412 IFC Averages 45 5 3.01 0.024 $3,829 1101 ** Chapter has not submitted this information to Fraternity & Sorority Life BGSU Greek Report Data - Multicultural Greek Council (MGC) Total Active Change in Money Total # of New Chapter New Mem. -

1 the Sigma Beta Chapter of Phi Mu Alpha Sinfonia

The Sigma Beta Chapter of Phi Mu Alpha Sinfonia Bylaws Adopted: January 31, 2013 Revisions: December 5th 2014 March 21st, 2016 January 29th, 2017 September 20, 2017 1 Table of Contents ARTICLE I ............................................................................................................................... 3 TITLE AND OBJECT ................................................................................................................. 3 ARTICLE II .............................................................................................................................. 3 OFFICERS ............................................................................................................................... 3 ARTICLE III ............................................................................................................................. 5 DUTIES OF OFFICERS .............................................................................................................. 5 ARTICLE IV ............................................................................................................................. 7 MEETINGS ............................................................................................................................. 7 ARTICLE V ............................................................................................................................ 10 CHAPTER COMMITTEES ....................................................................................................... 10 ARTICLE VI -

03-04 Layout 1

From the National Collegiate Representative By Erick Reid, Rho Mu (Norfolk I look forward to meeting many of you this State) 2008, National Collegiate summer at Leadership Institute. This year’s event Representative promises to be even bigger than last year’s record- Greetings Brothers! setting attendance. We’ll have inspiring speakers, I pray that you are having a opportunities for brotherhood, and the excellent great semester so far and staying learning will take place as usual. Mark your calen- on top of those many resolutions dar now and make sure you’re in Evansville this that were stated this New Year’s. coming summer. This experience is one that I have As you approach the end of the enjoyed over the years and has truly become the semester, take a look back at highlight of my summers! some of those goals and measure This issue of the Red and Black is a special one! how well you are doing and where you will need You will have the opportunity to read more excit- improvement to stay on task this year! There is a ing information about Percy Jewett Burrell and the song that is playing all over the world right now topic no one likes to talk about, Risk Management. called “Happy” by Pharrell Williams. I listen to Although risk management is a touchy topic, I this song quite often to remind myself that things encourage you to learn more about it so you can are not always as bad as they seem. Try to find ensure your chapter is doing its due diligence. -

Masculinity, Race, and a Southern University: an Exploration of the Role of Fraternities in College Life

Andrew C. Patty Graduate Student- Divinity School Masculinity, Race, and a Southern University: An Exploration of the Role of Fraternities in College Life During my senior year in college, the history honors program required the writing of a focus paper on a subject that was of new interest to the student. This gave the students the muscles to flex their historical skills to an area that might not have been their concentration. At the time, I was very involved with Greek life as Vice President of the Inter-Fraternity Council and had many questions about the formation of fraternities. Therefore, I took the leap and started a detailed study of Greek life at the University of the South. In the conclusion of the paper, I focused on the integration of African Americans into White Social Fraternities at the national/regional level and at The University of the South: Sewanee. In the writing of this paper, it quickly became obvious that the area of historical study of Greek life has been of less importance in the field of High Education. The task of historical writing has largely been left to those in the fraternities and often do not include the relationships that are developed between fraternities and how they influenced collegiate life. Therefore, I had to source materials across many schools to find the lost narrative of fraternal lives in our universities. The differences in the influence that Greek organizations had on the social life of students and the views on integration were very interesting. It shows that often fraternity chapters were more reflective of the general student body of the school than they were as a national organization. -

GREEK LIFE GRADE REPORT Fall 2019

GREEK LIFE GRADE REPORT Fall 2019 Office of Greek Life Student Center, Office 104 F, G and H SUMMARY CHAPTER REPORT GPAs are calculated on active membership of organizations (identified on organization’s rosters submitted to the Office of Greek Life) and includes any new members brought into the organization recorded at the end of Fall 2019 semester. COMPARISON BREAKDOWN Cumulative GPAs Only GPAs are calculated on active membership of organizations (identified on organization’s rosters submitted to the Office of Greek Life) and includes any new members brought into the organization recorded at the end of Fall 2019 semester. ** Indicates that the chapter has 3 or less members at the end of the semester and therefore grades are kept private to the public ** CHAPTER REPORT ORGANIZATION Fall 19 GPA Cumulative GPA Alpha Chi Rho 3.301 3.276 Alpha Iota Chi 3.123 3.213 Alpha Kappa Alpha 3.043 3.242 Alpha Phi Alpha *** *** Alpha Phi Delta 2.889 3.02 Alpha Phi Omega 3.474 3.457 Alpha Sigma Rho (Colony) 3.283 3.283 Chi Upsilon Sigma 2.977 2.89 Delta Chi 3.156 3.176 Delta Phi Epsilon 3.405 3.345 Delta Sigma Iota *** *** Delta Xi Delta 3.237 3.308 Iota Phi Theta *** *** Kappa Sigma 3.414 3.359 Lambda Sigma Upsilon 2.828 2.926 Lambda Tau Omega 2.834 2.973 Lambda Theta Alpha 3.018 3.206 Lambda Theta Phi *** *** Lambda Upsilon Lambda 2.854 2.993 Mu Sigma Upsilon 2.103 2.899 Omega Phi Chi 2.904 3.085 Omega Psi Phi *** *** Phi Beta Sigma *** *** Phi Alpha Psi Senate *** *** Phi Delta Theta (Colony) 3.472 3.41 Phi Mu Alpha Sinfonia 3.382 3.349 Phi Sigma -

School of Music 1

School of Music 1 awarding of scholarships to deserving students. For information, visit: SCHOOL OF MUSIC www.financialaid.umd.edu (http://www.financialaid.umd.edu). College of Arts and Humanities Awards and Recognition 2110 Clarice Smith Performing Arts Center The Presser Award is granted each May to a music student with junior 301-405-5549 standing who demonstrates both performance and scholastic excellence, www.music.umd.edu (http://www.music.umd.edu) as determined by the music faculty, and carries with it a significant The objectives of the School of Music are: financial award to help the recipient in his/her senior year. 1. to provide a professional musical education based on a foundation in Academic Programs and Departmental the liberal arts; 2. to help students understand music as an artistic and cultural product; Facilities 3. to prepare the student for professional and graduate work in the field; The UMD School of Music is located in the Clarice Smith Performing and Arts Center, a 318,000 square foot campus facility dedicated to Music, Theatre, Dance and Performance Studies. Completed in 2001, the center 4. to prepare the student to teach music in the public schools. includes six state-of-the-art performance venues, the Michelle Smith Programs Performing Arts Library, and specialized classroom and rehearsal spaces. Major • Music Major (https://academiccatalog.umd.edu/undergraduate/ colleges-schools/arts-humanities/music/music-major/) Minor • Music and Culture Minor (https://academiccatalog.umd.edu/ undergraduate/colleges-schools/arts-humanities/music/music- culture-minor/) • Music Performance Minor (https://academiccatalog.umd.edu/ undergraduate/colleges-schools/arts-humanities/music/music- performance-minor/) Advising Departmental advising is mandatory for all music majors every semester. -

The-Phota-Vol-2-Issue-1-2014

The Phota Fraternity and Sorority Newsletter The Phota (the Greek word for lights) is a publication of the Valparaiso University Panhellenic and Interfraternity Councils January 2014 Over 200 New Members Join Fraternities and Sororities at Valpo in January 2014 The Valparaiso University fraternity and sorority community is excited to welcome more than 200 new members to the community in January 2014. Both the Panhellenic and Interfraternity Councils had record years regarding participation in member recruitment activities. The results of the January 2014 formal recruitment periods for both fraternities and sororities are as follows: Chi Omega – 20 Gamma Phi Beta – 17 Kappa Delta – 18 Kappa Kappa Gamma – 24 Calendar of Events Pi Beta Phi – 20 Jan. 30: Order of Omega Meeting at 8 pm at 807 Mound Street Lambda Chi Alpha – 11 Feb. 1: 2nd Annual Dance Marathon from 2-10 pm at Hilltop Gym Phi Delta Theta – 16 Feb 3: Officer Roundtables at 9 pm Phi Kappa Psi – 13 o Philanthropy/Service Chairs – Ballroom B Phi Mu Alpha Sinfonia – 9 o Public Relations Chairs – Heritage Room Phi Sigma Kappa – 7 o Alumnae Relations Chairs – Victory Bell Room Sigma Chi – 14 Feb 7: Phi Kappa Psi Chili Cook-Off at 5 pm at 801 Mound Street Sigma Phi Epsilon – 28 Sigma Pi - 4 www.Valpo.edu/greek Vol. 2 Issue 1 Fraternities & Sororities Light Up Christmas On December 5, 2013, Valparaiso University celebrated the beginning of the Christmas season with an evening of festivities including the first Jingle Jog, the annual tree lighting ceremony, and a fireworks display. Members of Kappa Delta sorority and Phi Sigma Kappa fraternity were asked to sing carols at the ceremony where President Heckler officially lit the University tree. -

For More Information About Organizations at the University Of

Engineers Climbing Club American Society of Civil Engineers Cognition, Learning, and Development Student American Society of Interior Designers Organization American Society of Landscape Architects Student College of Agricultural Sciences & Natural Chapter Resources Advisory Board American Society of Mechanical Engineers College of Business Administration Student For more information about organizations at Amnesty International Advisory Board the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, check out Animal Science Graduate Student Association College of Business Administration Student involved.unl.edu or call Student Involvement Anthro Group Ambassador Program at 402.472.6797 Arnold Air Society College of Education & Human Sciences Advisory Art League Board 453 Disaster Relief Art Without Walls College of Engineering Ambassadors Abel Residence Association Arts and Sciences Student Advisory Board College of Journalism and Mass Communications ACACIA Asian World Alliance (CoJMC) Ambassadors Actuarial Science Club Associated General Contractors College Republicans Advertising Club Association for Computing Machinery Collegiate Entrepreneurs Organization Afghan Renascent Youth Association Association of Non-Traditional Students Collegiate Music Educators National Conference Afghan Student Association ASUN “Communication Studies Club, UNL” African Student Association Athletic Training Student Association Computer Science and Engineering Graduate Afrikan Peoples Union Azerbaijani American Association Student Association Agricultural Communicators of Tomorrow -

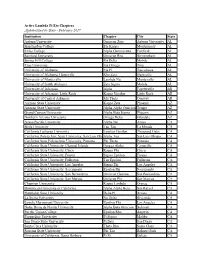

Active Lambda Pi Eta Chapters Alphabetized by State

Active Lambda Pi Eta Chapters Alphabetized by State - February 2017 Institution Chapter City State Auburn University Omicron Zeta Auburn University AL Huntingdon College Eta Kappa Montgomery AL Miles College Alpha Gamma Iota Fairfield AL Samford University Omicron Rho Birmingham AL Spring Hill College Psi Delta Mobile AL Troy University Eta Omega Troy AL University of Alabama Eta Pi Tuscaloosa AL University of Alabama, Huntsville Rho Zeta Huntsville AL University of Montevallo Lambda Nu Montevallo AL University of South Alabama Zeta Sigma Mobile AL University of Arkansas Alpha Fayetteville AR University of Arkansas, Little Rock Kappa Upsilon Little Rock AR University of Central Arkansas Mu Theta Conway AR Arizona State University Kappa Zeta Phoenix AZ Arizona State University Alpha Alpha Omicron Tempe AZ Grand Canyon University Alpha Beta Sigma Phoenix AZ Northern Arizona University Omega Delta Glendale AZ Azusa Pacific University Alpha Nu Azusa CA Biola University Tau Tau La Mirada CA California Lutheran University Upsilon Upsilon Thousand Oaks CA California Polytechnic State University, San Luis ObispoAlpha Tau San Luis Obispo CA California State Polytechnic University, Pomona Phi Theta Pomona CA California State University, Channel Islands Omega Alpha Camarillo CA California State University, Chico Kappa Phi Chico CA California State University, Fresno Sigma Epsilon Fresno CA California State University, Fullerton Tau Epsilon Fullerton CA California State University, Los Angeles Sigma Phi Los Angeles CA California State University, -

Fall 2010 Greek Report Interfraternity Council (IFC) Rank Chapter Sem

Fraternity and Sorority Life Office of Residence Life Division of Student Affairs Bowling Green State University: Fall 2010 Greek Report Interfraternity Council (IFC) Rank Chapter Sem. GPA Cum. GPA Total # Involvement % Money Donated to Community Academic Incentives Philanthropies Service Hours Awarded 1 Lambda Chi Alpha 3.0000 2.8876 34 2 Phi Kappa Psi 2.8655 2.8973 26 276 3 Alpha Tau Omega 2.8283 2.9667 25 28% $4000.00 160 4 Alpha Sigma Phi 2.6896 2.8968 45 75.6% $2000.00 379 $20.00 5 Phi Delta Theta 2.6565 2.9067 25 6 Tau Kappa Epsilon (Colony) 2.6179 2.7635 32 31.3% $471.00 137.5 $5.00 7 Pi Kappa Phi 2.5919 2.7305 26 8 Delta Chi 2.5865 2.8011 31 9 Sigma Alpha Epsilon 2.5536 2.5957 17 10 Pi Kappa Alpha 2.5328 2.7132 81 11 Sigma Nu 2.5260 2.9009 17 12 Kappa Sigma 2.5010 2.7106 37 8.1% $375.00 78 $3500.00 13 Delta Tau Delta 2.4173 2.6388 30 102 14 Phi Gamma Delta (FIJI) 2.3881 2.5702 37 15 Kappa Alpha Order 2.3543 2.5115 29 16 Sigma Phi Epsilon 2.2663 2.6692 49 20% $1300.00 450 None National Pan-Hellenic Council (NPHC) Rank Chapter Sem. GPA Cum. GPA Total # Involvement % Money Donated to Community Academic Incentives Philanthropies Service Hours Awarded 1 Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Inc. 3.2812 3.3133 7 57.1% $140 20 None 2 Kappa Alpha Psi Fraternity, Inc. -

Fall-2018-FSL-Community-Report.Pdf

COMMUNITY REPORT Presented by Fraternity and Sorority Life Bowling Green State University ● Fall 2018 Important Spring 2019 Dates January 28 First Day of classes February 5 February Presidents Gathering February 7- February 10 AFLV/NBGLC in indianapolis, indiana February 18- February 22 fsl showcase week March 5 march presidents gathering March 6 advisor roundtable March 18- March 22 spring break March 29 gsoe goal completion deadline April 2 april presidents gathering april 3 gsoe roundatable April 24 Advisor Roundtable April 25- April 28 greek weekend May 2 greek gala May 7 may presidents gathering May 17- May 18 graduation Community Impact 12.56% 14,726.5 $46,912.08 of our campus is active in a social total service hours Total Dollars raised greek-lettered organization! completed in fall 2018 in fall 2018 Fall 2018 Total Community Size 1836 MEMBERSHIP Interfraternity Council 814 Multicultural Greek Council 78 National Pan-Hellenic Council 36 Panhellenic Association 908 Total active Total new Spring 18 to Fall 17 to Fall Council Members Members Fall 18 Change 18 Change ΑΤΩ ALPHA TAU OMEGA IFC 29 33 25 20 ΣΧ SIGMA CHI IFC 42 21 16 18 ΣΚ SIGMA KAPPA PHA 51 25 12 13 ΚΣ KAPPA SIGMA IFC 58 15 5 9 ΠΒΦ PI BETA PHI PHA 61 27 9 9 ΑΣΦ ALPHA SIGMA PHI IFC 49 14 7 8 ΑΞΔ ALPHA XI DELTA PHA 55 26 5 7 ΔΓ DELTA GAMMA PHA 59 25 5 7 ΚΔ KAPPA DELTA PHA 61 26 7 6 ΠΚΑ PI KAPPA ALPHA IFC 68 18 12 6 ΑΧΩ ALPHA CHI OMEGA PHA 58 27 9 4 ΣΓΡ SIGMA GAMMA RHO NPHC 9 0 -3 4 TKE TAU KAPPA EPSILON IFC 62 17 6 3 ΣΝ SIGMA NU IFC 15 9 6 1 ΑΦΑ ALPHA PHI ALPHA NPHC 6 0 0 -

Society of Women Engineers Omega Phi Alpha Pre-Dental Association at Eastern Michigan University Professional Development Sellin

Neuroscience Interdisciplinary Council The Neuroscience Interdisciplinary Council is a public student organization that aids students in recognizing and learning about the studies involving neuroscience. NIC provides aspiring students in the pre-health fields to get involved and learn about the brain and nervous systems along with public representation of leaders in today’s neuroscience fields. Omega Phi Alpha Omega Phi Alpha is the only National Service Sorority on Eastern Michigan University's campus. Our cardinal principles are friendship, leadership, and service. We promote service to the university community, community at large, members of the sorority, and nations of the world. Optimize Eastern Optimize is a social entrepreneurship organization that focuses on inspiring students. Pre-Dental Association at Eastern Michigan University The Pre-Dental Association at Eastern Michigan University is a campus organization devoted to providing guidance to the undergraduate interested in a future in dentistry or related fields. The club provides up to date information used in the profession. Pre-med Club The purpose of the EMU Pre-medicine Club is to provide academic and service opportunities, as well as fellowship for pre-medical professional students on campus. We welcome any and all students who are interested in medicine or are planning a future career as a health professional and who are seeking to be involved in beneficial pre-medicine experiences and volunteer opportunities. Professional Development Selling Club The Professional Development and Selling Club aims to grow professional selling skills, increase networking opportunities, and set students up for career success. Project Big Sister Woman empowerment organization and we focus on women between the ages 12-19.