From Network Microeconomics to Network Infrastructure Emergence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deflation: a Business Perspective

Deflation: a business perspective Prepared by the Corporate Economists Advisory Group Introduction Early in 2003, ICC's Corporate Economists Advisory Group discussed the risk of deflation in some of the world's major economies, and possible consequences for business. The fear was that historically low levels of inflation and faltering economic growth could lead to deflation - a persistent decline in the general level of prices - which in turn could trigger economic depression, with widespread company and bank failures, a collapse in world trade, mass unemployment and years of shrinking economic activity. While the risk of deflation is now remote in most countries - given the increasingly unambiguous signs of global economic recovery - its potential costs are very high and would directly affect companies. This issues paper was developed to help companies better understand the phenomenon of deflation, and to give them practical guidance on possible measures to take if and when the threat of deflation turns into reality on a future occasion. What is deflation? Deflation is defined as a sustained fall in an aggregate measure of prices (such as the consumer price index). By this definition, changes in prices in one economic sector or falling prices over short periods (e.g., one or two quarters) do not qualify as deflation. Dec lining prices can be driven by an increase in supply due to technological innovation and rapid productivity gains. These supply-induced shocks are usually not problematic and can even be accompanied by robust growth, as experienced by China. A fall in prices led by a drop in demand - due to a severe economic cycle, tight economic policies or a demand-side shock - or by persistent excess capacity can be much more harmful, and is more likely to lead to persistent deflation. -

Carbonomics Innovation, Deflation and Affordable De-Carbonization

EQUITY RESEARCH | October 13, 2020 | 9:24PM BST Carbonomics Innovation, Deflation and Affordable De-carbonization Net zero is becoming more affordable as technological and financial innovation, supported by policy, are flattening the de-carbonization cost curve. We update our 2019 Carbonomics cost curve to reflect innovation across c.100 different technologies to de- carbonize power, mobility, buildings, agriculture and industry, and draw three key conclusions: 1) low-cost de-carbonization technologies (mostly renewable power) continue to improve consistently through scale, reducing the lower half of the cost curve by 20% on average vs. our 2019 cost curve; 2) clean hydrogen emerges as the breakthrough technology in the upper half of the cost curve, lowering the cost of de-carbonizing emissions in more difficult sectors (industry, heating, heavy transport) by 30% and increasing the proportion of abatable emissions from 75% to 85% of total emissions; and 3) financial innovation and a lower cost of capital for low-carbon activities have driven around one-third of renewables cost deflation since 2010, highlighting the importance of shareholder engagement in climate change, monetary stimulus and stable regulatory frameworks. The result of these developments is very encouraging, shaving US$1 tn pa from the cost of the path towards net zero and creating a broader connected ecosystem for de- carbonization that includes renewables, clean hydrogen (both blue and green), batteries and carbon capture. Michele Della Vigna, CFA Zoe Stavrinou Alberto Gandolfi +44 20 7552-9383 +44 20 7051-2816 +44 20 7552-2539 [email protected] [email protected] alberto.gandolfi@gs.com Goldman Sachs International Goldman Sachs International Goldman Sachs International Goldman Sachs does and seeks to do business with companies covered in its research reports. -

The Great Divergence the Princeton Economic History

THE GREAT DIVERGENCE THE PRINCETON ECONOMIC HISTORY OF THE WESTERN WORLD Joel Mokyr, Editor Growth in a Traditional Society: The French Countryside, 1450–1815, by Philip T. Hoffman The Vanishing Irish: Households, Migration, and the Rural Economy in Ireland, 1850–1914, by Timothy W. Guinnane Black ’47 and Beyond: The Great Irish Famine in History, Economy, and Memory, by Cormac k Gráda The Great Divergence: China, Europe, and the Making of the Modern World Economy, by Kenneth Pomeranz THE GREAT DIVERGENCE CHINA, EUROPE, AND THE MAKING OF THE MODERN WORLD ECONOMY Kenneth Pomeranz PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS PRINCETON AND OXFORD COPYRIGHT 2000 BY PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS PUBLISHED BY PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS, 41 WILLIAM STREET, PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY 08540 IN THE UNITED KINGDOM: PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS, 3 MARKET PLACE, WOODSTOCK, OXFORDSHIRE OX20 1SY ALL RIGHTS RESERVED LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA POMERANZ, KENNETH THE GREAT DIVERGENCE : CHINA, EUROPE, AND THE MAKING OF THE MODERN WORLD ECONOMY / KENNETH POMERANZ. P. CM. — (THE PRINCETON ECONOMIC HISTORY OF THE WESTERN WORLD) INCLUDES BIBLIOGRAPHICAL REFERENCES AND INDEX. ISBN 0-691-00543-5 (CL : ALK. PAPER) 1. EUROPE—ECONOMIC CONDITIONS—18TH CENTURY. 2. EUROPE—ECONOMIC CONDITIONS—19TH CENTURY. 3. CHINA— ECONOMIC CONDITIONS—1644–1912. 4. ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT—HISTORY. 5. COMPARATIVE ECONOMICS. I. TITLE. II. SERIES. HC240.P5965 2000 337—DC21 99-27681 THIS BOOK HAS BEEN COMPOSED IN TIMES ROMAN THE PAPER USED IN THIS PUBLICATION MEETS THE MINIMUM REQUIREMENTS OF ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R1997) (PERMANENCE OF PAPER) WWW.PUP.PRINCETON.EDU PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA 3579108642 Disclaimer: Some images in the original version of this book are not available for inclusion in the eBook. -

The First Great Divergence

Mellon-Sawyer Seminar 2007/8 “The first great divergence: China and Europe, 500-800 CE” Organized by Ian Morris, Walter Scheidel, and Mark Lewis, Departments of Classics and History, Stanford University Sponsored by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Six hundred years ago China was the most powerful state on earth. The eunuch admiral Zheng He spent 1406 cruising around the Indian Ocean at the head of 30,000 crew in a fleet of giant Chinese “treasure ships,” trading, collecting tribute, and setting up and deposing client kings at will. By 1433, Chinese ships were visiting Arabia, Ethiopia, and Kenya, and probably Australia too. By any reasonable estimate, China seemed set to become the world’s first global power. But that did not happen. Anti-trade Confucian factions won out in struggles at the Ming court, and long-distance voyages were banned. By 1467, most records of Zheng’s voyages were lost or destroyed. Half a millennium later, far from dominating as the world, China seemed – at least to western observers – to be going backward. When a dispute over opium trading escalated uncontrollably in 1839, the British sent a small naval force to claim damages from the governor of Canton. A single ironclad gunboat blasted its way through all the Chinese defenses, and in 1842, with the Grand Canal under British control, Nanjing facing plunder, and famine closing in on Beijing, China conceded British demands for open ports and the right to send missionaries deep into the country. This defeat triggered crises that brought China to the verge of partition. One Hong Xiuquan, a failed civil service candidate who developed his own bizarre version of Christianity out of the teachings of the missionaries at Canton, led the massive Taiping Rebellion to install a Heavenly Kingdom of Great Peace. -

The Keynesian Model in the General Theory: a Tutorial

The Keynesian Model in the General Theory: A Tutorial Raúl Rojas Freie Universität Berlin January 2012 This small overview of the General Theory is the kind of summary I would have liked to have read, before embarking in a comprehensive study of the General Theory at the time I was a student. As shown here, the main ideas are quite simple and easy to visualize. Unfortunately, numerous introductions to Keynesian theory are not actually based on Keynes opus magnum, but in obscure neo‐classical reinterpretations. This is completely pointless since Keynes’ book is so readable. Introduction John Maynard Keynes (1883‐1946) completed the General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money [1] in December of 1935, right in the middle of the Great Depression. At that point, millions of workers in the US and Europe had been unemployed for years, and economic orthodoxy could not account for this “anomalous” situation. Keynes’ General Theory tries to tackle exactly this problem. Keynes rejected classical theories based on the idea that production creates its own demand, that is, that the economy always recovers to full employment after a shock. Therefore, Keynes called his treatise the General Theory because he conceived classical doctrine as only a special case of a more complete approach: “The classical theorists resemble Euclidean geometers in a non‐Euclidean world who, discovering that in experience straight lines apparently parallel often meet, rebuke the lines for not keeping straight (...) Yet, in truth, there is no remedy except to throw over the axiom of parallels and to work out a non‐Euclidean geometry. -

A Primer on Modern Monetary Theory

2021 A Primer on Modern Monetary Theory Steven Globerman fraserinstitute.org Contents Executive Summary / i 1. Introducing Modern Monetary Theory / 1 2. Implementing MMT / 4 3. Has Canada Adopted MMT? / 10 4. Proposed Economic and Social Justifications for MMT / 17 5. MMT and Inflation / 23 Concluding Comments / 27 References / 29 About the author / 33 Acknowledgments / 33 Publishing information / 34 Supporting the Fraser Institute / 35 Purpose, funding, and independence / 35 About the Fraser Institute / 36 Editorial Advisory Board / 37 fraserinstitute.org fraserinstitute.org Executive Summary Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) is a policy model for funding govern- ment spending. While MMT is not new, it has recently received wide- spread attention, particularly as government spending has increased dramatically in response to the ongoing COVID-19 crisis and concerns grow about how to pay for this increased spending. The essential message of MMT is that there is no financial constraint on government spending as long as a country is a sovereign issuer of cur- rency and does not tie the value of its currency to another currency. Both Canada and the US are examples of countries that are sovereign issuers of currency. In principle, being a sovereign issuer of currency endows the government with the ability to borrow money from the country’s cen- tral bank. The central bank can effectively credit the government’s bank account at the central bank for an unlimited amount of money without either charging the government interest or, indeed, demanding repayment of the government bonds the central bank has acquired. In 2020, the cen- tral banks in both Canada and the US bought a disproportionately large share of government bonds compared to previous years, which has led some observers to argue that the governments of Canada and the United States are practicing MMT. -

The Impact of Inflation on Social Security Benefits

RETIREMENT RESEARCH August 2021, Number 21-14 THE IMPACT OF INFLATION ON SOCIAL SECURITY BENEFITS By Alicia H. Munnell and Patrick Hubbard* Introduction This fall, the U.S. Social Security Administration is The third section explores how inflation affects the likely to announce that benefits will be increased by taxation of benefits. The final section concludes that, around 6 percent beginning January 1, 2022. This while the inflation adjustment in Social Security is ex- cost-of-living-adjustment (COLA), which would be tremely valuable, the rise in Medicare premiums and the largest in 40 years, is an important reminder that the extension of taxation under the personal income keeping pace with inflation is one of the attributes tax limits the ability of beneficiaries to fully maintain that makes Social Security benefits such a unique their purchasing power. source of retirement income. A spurt in inflation, however, affects two other factors that determine the net amount that retirees Social Security’s COLA receive from Social Security. The first is the Medicare premiums for Part B, which are deducted automati- Social Security benefits are subject each year to a 1 cally from Social Security benefits. To the extent that COLA. This adjustment, based on the change in the premiums rise faster than the COLA, the net benefit Consumer Price Index for Urban Wage Earners and will not keep pace with inflation. The second issue Clerical Workers (CPI-W) over the last year, protects pertains to taxation under the personal income tax. beneficiaries against the effects of inflation. Without Because taxes are levied on Social Security benefits such automatic adjustments, the government would only for households with income above certain have to make frequent changes to benefits to prevent 2 thresholds ($25,000 for single taxpayers and $32,000 retirees’ standard of living from eroding as they age. -

The Basic Economics of Internet Infrastructure

Journal of Economic Perspectives—Volume 34, Number 2—Spring 2020—Pages 192–214 The Basic Economics of Internet Infrastructure Shane Greenstein his internet barely existed in a commercial sense 25 years ago. In the mid- 1990s, when the data packets travelled to users over dial-up, the main internet T traffic consisted of email, file transfer, and a few web applications. For such content, users typically could tolerate delays. Of course, the internet today is a vast and interconnected system of software applications and computing devices, which society uses to exchange information and services to support business, shopping, and leisure. Not only does data traffic for streaming, video, and gaming applications comprise the majority of traffic for internet service providers and reach users primarily through broadband lines, but typically those users would not tolerate delays in these applica- tions (for usage statistics, see Nevo, Turner, and Williams 2016; McManus et al. 2018; Huston 2017). In recent years, the rise of smartphones and Wi-Fi access has supported growth of an enormous range of new businesses in the “sharing economy” (like, Uber, Lyft, and Airbnb), in mobile information services (like, social media, ticketing, and messaging), and in many other applications. More than 80 percent of US households own at least one smartphone, rising from virtually zero in 2007 (available at the Pew Research Center 2019 Mobile Fact Sheet). More than 86 percent of homes with access to broadband internet employ some form of Wi-Fi for accessing applications (Internet and Television Association 2018). It seems likely that standard procedures for GDP accounting underestimate the output of the internet, including the output affiliated with “free” goods and the restructuring of economic activity wrought by changes in the composition of firms who use advertising (for discussion, see Nakamura, Samuels, and Soloveichik ■ Shane Greenstein is the Martin Marshall Professor of Business Administration, Harvard Business School, Boston, Massachusetts. -

Modern Monetary Theory: a Marxist Critique

Class, Race and Corporate Power Volume 7 Issue 1 Article 1 2019 Modern Monetary Theory: A Marxist Critique Michael Roberts [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/classracecorporatepower Part of the Economics Commons Recommended Citation Roberts, Michael (2019) "Modern Monetary Theory: A Marxist Critique," Class, Race and Corporate Power: Vol. 7 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. DOI: 10.25148/CRCP.7.1.008316 Available at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/classracecorporatepower/vol7/iss1/1 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts, Sciences & Education at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Class, Race and Corporate Power by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Modern Monetary Theory: A Marxist Critique Abstract Compiled from a series of blog posts which can be found at "The Next Recession." Modern monetary theory (MMT) has become flavor of the time among many leftist economic views in recent years. MMT has some traction in the left as it appears to offer theoretical support for policies of fiscal spending funded yb central bank money and running up budget deficits and public debt without earf of crises – and thus backing policies of government spending on infrastructure projects, job creation and industry in direct contrast to neoliberal mainstream policies of austerity and minimal government intervention. Here I will offer my view on the worth of MMT and its policy implications for the labor movement. First, I’ll try and give broad outline to bring out the similarities and difference with Marx’s monetary theory. -

Employment Situation of Veterans — 2020

For release 10:00 a.m. (ET) Thursday, March 18, 2021 USDL-21-0438 Technical information: (202) 691-6378 • [email protected] • www.bls.gov/cps Media contact: (202) 691-5902 • [email protected] EMPLOYMENT SITUATION OF VETERANS — 2020 The unemployment rate for veterans who served on active duty in the U.S. Armed Forces at any time since September 2001—a group referred to as Gulf War-era II veterans—rose to 7.3 percent in 2020, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported today. The jobless rate for all veterans increased to 6.5 percent in 2020. These increases reflect the effect of the coronavirus (COVID- 19) pandemic on the labor market. In August 2020, 40 percent of Gulf War-era II veterans had a service-connected disability, compared with 26 percent of all veterans. This information was obtained from the Current Population Survey (CPS), a monthly sample survey of about 60,000 eligible households that provides data on employment, unemployment, and persons not in the labor force in the United States. Data about veterans are collected monthly in the CPS; these monthly data are the source of the 2020 annual averages presented in this news release. In August 2020, a supplement to the CPS collected additional information about veterans on topics such as service-connected disability and veterans' current or past Reserve or National Guard membership. Information from the supplement is also presented in this news release. The supplement was co-sponsored by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and the U.S. Department of Labor's Veterans' Employment and Training Service. -

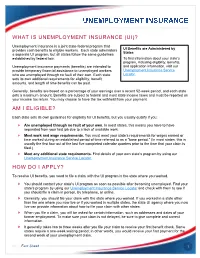

What Is Unemployment Insurance (Ui)? Am I Eligible? How Do I Apply?

WHAT IS UNEMPLOYMENT INSURANCE (UI)? Unemployment Insurance is a joint state-federal program that provides cash benefits to eligible workers. Each state administers UI Benefits are Administered by States a separate UI program, but all states follow the same guidelines established by federal law. To find information about your state’s program, including eligibility, benefits, Unemployment insurance payments (benefits) are intended to and application information, visit our provide temporary financial assistance to unemployed workers Unemployment Insurance Service who are unemployed through no fault of their own. Each state Locator. sets its own additional requirements for eligibility, benefit amounts, and length of time benefits can be paid. Generally, benefits are based on a percentage of your earnings over a recent 52-week period, and each state sets a maximum amount. Benefits are subject to federal and most state income taxes and must be reported on your income tax return. You may choose to have the tax withheld from your payment. AM I ELIGIBLE? Each state sets its own guidelines for eligibility for UI benefits, but you usually qualify if you: Are unemployed through no fault of your own. In most states, this means you have to have separated from your last job due to a lack of available work. Meet work and wage requirements. You must meet your state’s requirements for wages earned or time worked during an established period of time referred to as a "base period." (In most states, this is usually the first four out of the last five completed calendar quarters prior to the time that your claim is filed.) Meet any additional state requirements. -

A Glossary of Fiscal Terms & Acronyms

AUGUST7,1998VOLUME13,NO .VII A Publication of the House Fiscal Analysis Department on Government Finance Issues A GLOSSARY OF FISCAL TERMS & ACRONYMS 1998 Revised Edition Abstract. This issue of Money Matters is a resource document containing terms and acronyms commonly used by and in legislative fiscal committees and in the discussion of state budget and tax issues. The first section contains terms and abbreviations used in all fiscal committees and divisions. The remaining sections contain terms for particular budget categories and accounts, organized according to fiscal subject areas. This edition has new sections containing economic development, family and early childhood, and housing terms and acronyms. The other sections are revised and updated to reflect changes in terminology, particularly the human services section. For further information, contact the Chief Fiscal Analyst or the fiscal analyst assigned to the respective House fiscal committee or division. A directory of House Fiscal Analysis Department personnel and their committee/division assignments for the 1998 legislative session appears on the next page. Originally issued January 1997 Revised August 1998 House Fiscal Analysis Department Staff Assignments — 1998 Session Committee/Division Fiscal Analyst Telephone Room Chief Fiscal Analyst Bill Marx 296-7176 373 Capital Investment John Walz 296-8236 376 EDIT— Economic Development Finance CJ Eisenbarth Hager 296-5813 428 EDIT— Housing Finance Cynthia Coronado 296-5384 361 Environment & Natural Resources Finance Jim Reinholdz 296-4119 370 Education — Higher Education Finance Doug Berg 296-5346 372 K-12 Education Finance Greg Crowe 296-7165 378 Family & Early Childhood Finance Cynthia Coronado 296-5384 361 Health & Human Services Finance Joe Flores 296-5483 385 Judiciary Finance Gary Karger 296-4181 383 State Government Finance Helen Roberts 296-4117 374 Transportation Finance John Walz 296-8236 376 Taxes — Income, sales, misc.