Thylacine Conspiracy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Hunter and Biodiversity in Tasmania

The Hunter and Biodiversity in Tasmania The Hunter takes place on Tasmania’s Central Plateau, where “One hundred and sixty-five million years ago potent forces had exploded, clashed, pushed the plateau hundreds of metres into the sky.” [a, 14] The story is about the hunt for the last Tasmanian tiger, described in the novel as: “that monster whose fabulous jaw gapes 120 degrees, the carnivorous marsupial which had so confused the early explorers — a ‘striped wolf’, ‘marsupial wolf.’” [a, 16] Fig 1. Paperbark woodlands and button grass plains near Derwent Bridge, Central Tasmania. Source: J. Stadler, 2010. Biodiversity “Biodiversity”, or biological diversity, refers to variety in all forms of life—all plants and animals, their genes, and the ecosystems they live in. [b] It is important because all living things are connected with each other. For example, humans depend on living things in the environment for clean air to breathe, food to eat, and clean water to drink. Biodiversity is one of the underlying themes in The Hunter, a Tasmanian film directed by David Nettheim in 2011 and based on Julia Leigh’s 1999 novel about the hunt for the last Tasmanian Tiger. The film and the novel showcase problems that arise from loss of species, loss of habitat, and contested ideas about land use. The story is set in the Central Plateau Conservation Area and much of the film is shot just south of that area near Derwent Bridge and in the Florentine Valley. In Tasmania, land clearing is widely considered to be the biggest threat to biodiversity [c, d]. -

Thylacinidae

FAUNA of AUSTRALIA 20. THYLACINIDAE JOAN M. DIXON 1 Thylacine–Thylacinus cynocephalus [F. Knight/ANPWS] 20. THYLACINIDAE DEFINITION AND GENERAL DESCRIPTION The single member of the family Thylacinidae, Thylacinus cynocephalus, known as the Thylacine, Tasmanian Tiger or Wolf, is a large carnivorous marsupial (Fig. 20.1). Generally sandy yellow in colour, it has 15 to 20 distinct transverse dark stripes across the back from shoulders to tail. While the large head is reminiscent of the dog and wolf, the tail is long and characteristically stiff and the legs are relatively short. Body hair is dense, short and soft, up to 15 mm in length. Body proportions are similar to those of the Tasmanian Devil, Sarcophilus harrisii, the Eastern Quoll, Dasyurus viverrinus and the Tiger Quoll, Dasyurus maculatus. The Thylacine is digitigrade. There are five digital pads on the forefoot and four on the hind foot. Figure 20.1 Thylacine, side view of the whole animal. (© ABRS)[D. Kirshner] The face is fox-like in young animals, wolf- or dog-like in adults. Hairs on the cheeks, above the eyes and base of the ears are whitish-brown. Facial vibrissae are relatively shorter, finer and fewer than in Tasmanian Devils and Quolls. The short ears are about 80 mm long, erect, rounded and covered with short fur. Sexual dimorphism occurs, adult males being larger on average. Jaws are long and powerful and the teeth number 46. In the vertebral column there are only two sacrals instead of the usual three and from 23 to 25 caudal vertebrae rather than 20 to 21. -

The Earliest Motion Picture Footage of the Last Captive Thylacine? Stephen R

The earliest motion picture footage of the last captive thylacine? Stephen R. Sleightholme1 and Cameron R. Campbell2 1 Project Director - International Thylacine Specimen Database (ITSD), 26 Bitham Mill, Westbury, BA13 3DJ, UK. E-mail: [email protected] 2 Curator of the online Thylacine Museum: http://www.naturalworlds.org/thylacine/ 8707 Eagle Mountain Circle, Fort Worth, TX 76135, USA. E-mail: [email protected] Downloaded from http://meridian.allenpress.com/australian-zoologist/article-pdf/37/3/282/1587738/az_2014_021.pdf by guest on 02 October 2021 David Fleay’s 1933 motion film footage of the last captive thylacine at the Beaumaris Zoo in Hobart was thought to be the only film record of this thylacine. The authors provide evidence to confirm that two earlier motion picture films, erroneously dated to 1928, also show the last captive specimen at the zoo. ABSTRACT Key Words: Thylacine, Thylacinus cynocephalus, motion picture, Beaumaris Zoo, David Fleay. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7882/AZ.2014.021 Introduction The thylacine or Tasmanian tiger (Thylacinus cynocephalus) is the largest marsupial carnivore to have existed into modern times. The last known captive specimen, a male (Sleightholme, 2011), died at the Beaumaris Zoo on the Queen’s Domain in Hobart on the night of the 7th September 1936. There are seven historical motion picture films known to exist of captive thylacines, all of which were made between 1911 and 1933 (Fig. 1, [i-vii]) 1. Five of the films were recorded at the Beaumaris Zoo in Hobart, and the remaining two at the London Zoo, Regent’s Park. The earliest known footage was filmed by a Mr. -

The Perils of De-Extinction

MINDING NATURE 8.1 The Perils of De-extinction By BEN A. MINTEER TASMANIA’S LOST TIGER Neither tiger nor wolf, the “Thylacine” (as it became t wasn’t a tiger, at least not in the biological known after several taxonomic fits and starts), was, in sense. But in the cultural imagination of British fact, a marsupial mammal roughly the size of a hyena. It and Irish sheepherders transplanted to “Van Di- went extinct on the Australian mainland around 35,000 I emen’s Land” of the southeastern coast of Aus- years ago, a period that corresponded with the arrival of tralia in the early nineteenth century, the carnivorous, the dingo (the natural history of the species, however, is striped creature with the stealthy nature certainly ft a bit foggy). Tasmania, an island state around the size of the bill.1 Dubbed the Tasmanian tiger—or, alterna- Ireland or West Virginia, only ever held a small remnant tively, Tasmanian wolf (which it also was not)—the population of Thylacines, probably not more than five elusive animal was viewed as a threat to the island’s thousand at the time of British settlement in 1803.2 rapidly growing though ultimately ill-suited sheep in- The species would be decimated in the nineteenth dustry, an unwanted varmint that was also seen as an century by bounty hunters working at the behest of the impediment to the development of the Tasmanian wil- Van Diemen’s Land Company, a United Kingdom–based derness. wool-growing venture with a myopic desire for a pred- ator-free landscape. -

Convergent Regulatory Evolution and the Origin of Flightlessness in Palaeognathous Birds

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/262584; this version posted February 8, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Convergent regulatory evolution and the origin of flightlessness in palaeognathous birds Timothy B. Sackton* (1,2), Phil Grayson (2,3), Alison Cloutier (2,3), Zhirui Hu (4), Jun S. Liu (4), Nicole E. Wheeler (5,6), Paul P. Gardner (5,7), Julia A. Clarke (8), Allan J. Baker (9,10), Michele Clamp (1), Scott V. Edwards* (2,3) Affiliations: 1) Informatics Group, Harvard University, Cambridge, USA 2) Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University, Cambridge, USA 3) Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University, Cambridge, USA 4) Department of Statistics, Harvard University, Cambridge, USA 5) School of Biological Sciences, University of Canterbury, New Zealand 6) Wellcome Sanger Institute, Wellcome Genome Campus, Cambridge, UK 7) Department of Biochemistry, University of Otago, New Zealand 8) Jackson School of Geosciences, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, USA 9) Department of Natural History, Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, Canada 10) Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada *correspondence to: TBS ([email protected]) or SVE ([email protected]) bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/262584; this version posted February 8, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. The relative roles of regulatory and protein evolution in the origin and loss of convergent phenotypic traits is a core question in evolutionary biology. -

The Endangered Kiwi: a Review

REVIEW ARTICLE Folia Zool. – 54(1–2): 1–20 (2005) The endangered kiwi: a review James SALES Bosman street 39, Stellenbosch 7600, South Africa; e-mail: [email protected] Received 13 December 2004; Accepted 1 May 2005 A b s t r a c t . Interest in ratites has necessitated a review of available information on the unique endangered kiwi (Apteryx spp.). Five different species of kiwis, endemic to the three islands of New Zealand, are recognized by the Department of Conservation, New Zealand, according to genetic and biological differences: the North Island Brown Kiwi (Apteryx mantelli), Okarito Brown Kiwi/Rowi (A. rowi), Tokoeka (A. australis), Great Spotted Kiwi/Roroa (A. haastii), and Little Spotted Kiwi (A owenii). As predators were found to be the main reason for declining kiwi numbers, predator control is a main objective of management techniques to prevent kiwis becoming extinct in New Zealand. Further considerations include captive breeding and release, and establishment of kiwi sanctuaries. Body size and bill measurements are different between species and genders within species. Kiwis have the lowest basal rates of metabolism compared with all avian standards. A relative low body temperature (38 ºC), burrowing, a highly developed sense of smell, paired ovaries in females, and a low growth rate, separate kiwis from other avian species. Kiwis have long-term partnerships. Females lay an egg that is approximately 400 % above the allometrically expected value, with an incubation period of 75–85 days. Kiwis mainly feed on soil invertebrate, with the main constituent being earthworms, and are prone to parasites and diseases found in other avian species. -

Ontogenetic Origins of Cranial Convergence Between the Extinct Marsupial Thylacine and Placental Gray Wolf ✉ ✉ Axel H

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-020-01569-x OPEN Ontogenetic origins of cranial convergence between the extinct marsupial thylacine and placental gray wolf ✉ ✉ Axel H. Newton 1,2,3 , Vera Weisbecker 4, Andrew J. Pask2,3,5 & Christy A. Hipsley 2,3,5 1234567890():,; Phenotypic convergence, describing the independent evolution of similar characteristics, offers unique insights into how natural selection influences developmental and molecular processes to generate shared adaptations. The extinct marsupial thylacine and placental gray wolf represent one of the most extraordinary cases of convergent evolution in mammals, sharing striking cranial similarities despite 160 million years of independent evolution. We digitally reconstructed their cranial ontogeny from birth to adulthood to examine how and when convergence arises through patterns of allometry, mosaicism, modularity, and inte- gration. We find the thylacine and wolf crania develop along nearly parallel growth trajec- tories, despite lineage-specific constraints and heterochrony in timing of ossification. These constraints were found to enforce distinct cranial modularity and integration patterns during development, which were unable to explain their adult convergence. Instead, we identify a developmental origin for their convergent cranial morphologies through patterns of mosaic evolution, occurring within bone groups sharing conserved embryonic tissue origins. Inter- estingly, these patterns are accompanied by homoplasy in gene regulatory networks asso- ciated with neural crest cells, critical for skull patterning. Together, our findings establish empirical links between adaptive phenotypic and genotypic convergence and provides a digital resource for further investigations into the developmental basis of mammalian evolution. 1 School of Biomedical Sciences, Monash University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia. 2 School of BioSciences, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC, Australia. -

Gastrointestinal Parasites of a Population of Emus (Dromaius Novaehollandiae) in Brazil S

Brazilian Journal of Biology https://doi.org/10.1590/1519-6984.189922 ISSN 1519-6984 (Print) Original Article ISSN 1678-4375 (Online) Gastrointestinal parasites of a population of emus (Dromaius novaehollandiae) in Brazil S. S. M. Galloa , C. S. Teixeiraa , N. B. Ederlib and F. C. R. Oliveiraa* aLaboratório de Sanidade Animal – LSA, Centro de Ciências e Tecnologias Agropecuárias – CCTA, Universidade Estadual do Norte Fluminense – UENF, CEP 28035-302, Campos dos Goytacazes, RJ, Brasil bInstituto do Noroeste Fluminense de Educação Superior – INFES, Universidade Federal Fluminense – UFF, 28470-000, Santo Antônio de Pádua, RJ, Brasil *e-mail: [email protected] Received: January 9, 2018 – Accepted: June 19, 2018 – Distributed: February 28, 2020 (With 2 figures) Abstract Emus are large flightless birds in the ratite group and are native to Australia. Since the mid-1980s, there has been increased interest in the captive breeding of emus for the production of leather, meat and oil. The aim of this study was to identify gastrointestinal parasites in the feces of emus Dromaius novaehollandiae from a South American scientific breeding. Fecal samples collected from 13 birds were examined by direct smears, both with and without centrifugation, as well as by the fecal flotation technique using Sheather’s sugar solution. Trophozoites, cysts and oocysts of protozoa and nematode eggs were morphologically and morphometrically evaluated. Molecular analysis using PCR assays with specific primers for the genera Entamoeba, Giardia and Cryptosporidium were performed. Trophozoites and cysts of Entamoeba spp. and Giardia spp., oocysts of Eimeria spp. and Isospora dromaii, as well as eggs belonging to the Ascaridida order were found in the feces. -

Phylogeny, Transposable Element and Sex Chromosome Evolution of The

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/750109; this version posted August 28, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Phylogeny, transposable element and sex chromosome evolution of the basal lineage of birds Zongji Wang1,2,3,* Jilin Zhang4,*, Xiaoman Xu1, Christopher Witt5, Yuan Deng3, Guangji Chen3, Guanliang Meng3, Shaohong Feng3, Tamas Szekely6,7, Guojie Zhang3,8,9,10,#, Qi Zhou1,2,11,# 1. MOE Laboratory of Biosystems Homeostasis & Protection, Life Sciences Institute, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, 310058, China 2. Department of Molecular Evolution and Development, University of Vienna, Vienna, 1090, Austria 3. BGI-Shenzhen, Beishan Industrial Zone, Shenzhen 518083, China 4. Department of Medical Biochemistry and Biophysics, Karolinska Institutet, SE-171 77, Stockholm, Sweden 5. Department of Biology and the Museum of Southwestern Biology, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM 87131, USA 6. State Key Laboratory of Biocontrol, Department of Ecology, School of Life Sciences, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, 510275, China 7. Milner Center for Evolution, Department of Biology and Biochemistry, University of Bath, Bath, BA1 7AY, UK 8 State Key Laboratory of Genetic Resources and Evolution, Kunming Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming 650223, China 9. Section for Ecology and Evolution, Department of Biology, University of Copenhagen, DK-2100 Copenhagen, Denmark 10. Center for Excellence in Animal Evolution and Genetics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming, 650223, China 11. Center for Reproductive Medicine, The 2nd Affiliated Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University * These authors contributed equally to the work. -

Emu Production

This article was originally published online in 1996. It was converted to a PDF file, 10/2001 EMU PRODUCTION Dr. Joan S. Jefferey Extension Veterinarian Texas Agricultural Extension Service The Texas A&M University System Emus are native to Australia. Commercial production there and in the United States is a very recent development. The first emu producer's organization started in Texas in 1989. PRODUCTS Emu products include leather, meat and oil. Leather from emu hides is thinner and finer textured than ostrich leather. Anticipated uses include clothing and accessories. Emu meat, like ostrich meat, is being promoted as a low-fat, low-cholesterol red meat. Slaughter statistics from Emu Ranchers Incorporated (ERI) report average carcass weight is 80 pounds, with a 53.75 percent dressed yield. The average meat per carcass is 26 pounds and average fat is 17 pounds. ERI anticipates the sale price of emu meat to the public will be $20.00 per pound. A private company is processing under the name brand New Breed(r). New Breed(r) meat products include sausage, hot links and summer sausage at $15.00 per pound, jerky at $5.00 per packet and steak at $20.00 per pound. Emu oil, rendered from emu fat, is being used in skin care products in Australia (Emmuman(r)). One emu will yield 4 to 5 liters of oil. Emu producers in the U.S. are developing products and have two nearing the market stage: Emuri(r) Daytime Skin Therapy with Sunscreen (spf 8)- 1.7 ounces for $36.00; and Emuri(r) Night Revitalizing Cream - 1.7 ounces for $45.00. -

New World Extinctions: Where Next? Mammals: the Recently Departed

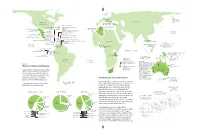

GERMANY BERING SEA Bavarian Commander I. pine vole 1962 EURASIA Stellerís sea cow NORTH 1768 CORSICA & SARDINIA AMERICA Sardinian pika Late 18th C. WEST INDIES CUBA MEDITERRANEAN Cuban spiny rats (2 species)* HAITI/ DOMINICAN REPUBLIC ALGERIA Hutia (6 species)* San Pedro Nolasco I. Cuban island shrews (4 species)* CANARY ISLANDS Red gazelle Arredondoís solenodon* Quemi* Volcano mouse* Late 19th c. Pembertonís Hispaniolan spiny rats (2 species)* deer mouse 1931 CAYMAN IS. Hispaniolan island shrews (3 species)* PACIFIC Cayman island shrews Marcanoís solenodon* OCEAN (2 species)* Maria Madre I. PUERTO RICO Nelsonís rice rat 1897 Cayman coneys (two species)* Puerto Rican spiny rats (2 species)* Cayman hutia* MEXICO Omilteme cottontail 1991 BARBUDA Barbuda muskrat* CARIBBEAN Little Swan I. Caribbean MARTINIQUE Martinique muskrat 1902 Little Swan Island coney 1950s-60s PHILIPPINES: Ilin I. Monk seal BARBADOS Barbados rice rat 1847-1890 AFRICA J AMAICA 1950s Small Ilin cloud rat 1953 Jamaican rice rat 1877 ST. VINCENT GUAM Jamaican monkey* St. Vincent rice rat 1890s Guam flying fox 1967 PACIFIC ST. LUCIA PHILIPPINES: Negros I. GHANA Philippine bare- OCEAN St. Lucia muskrat Groove-toothed forest CAROLINES: Palau I. pre-1881 backed fruit bat Palau flying fox 1874 mouse 1890 1975 GAL¡PAGOS ISLANDS San Salvador I. INDIAN OCEAN San Salvador rice rat 1965 Santa Cruz I. Curioís large rice rat* SOLOMON ISLANDS: Guadalcanal Isabela I. Gal·pagos rice rat Little pig rat 1887 Large rice rat* 1930s TANZANIA Giant naked-tailed rat 1960s Small rice rats (2 species)* Painted bat 1878 NEW GUINEA CHRISTMAS I. Large-eared Maclearís rat 1908 nyctophilus (bat) 1890 MADAGASCAR Bulldog rat 1908 Santa Cruz I. -

Disclosure and Revision in Photographs of the Thylacine

Society and Animals 15 (2007) 241-256 www.brill.nl/soan Imaging Extinction: Disclosure and Revision in Photographs of the Th ylacine (Tasmanian tiger) Carol Freeman Honorary Research Associate, School of Geography & Environmental Studies, University of Tasmania, Private Bag 78, HOBART Tasmania 7001 Email [email protected] Received 15 December 2006, Accepted 14 March 2007 Abstract Th e thylacine was a shy and elusive nonhuman animal who survived in small numbers on the island of Tasmania, Australia, when European settlers arrived in 1803. After a deliberate cam- paign of eradication, the species disappeared 130 years later. Visual and verbal constructions in the nineteenth century labeled the thylacine a ferocious predator, but photographs of individuals in British and American zoos that were used to illustrate early twentieth-century zoological works presented a very different impression of the animal. Th e publication of these photographs, however, had little effect on the relentless progress of extermination. Th is essay focuses on the relationship between photographs of thylacines and the process of extinction, between images and words, and between pictures of dead animals and live ones. Th e procedures, claims, and limitations of photography are crucial to the messages generated by these images and to the role they played in the representation of the species. Th is essay explains why the medium of photog- raphy and pleas for preservation could not save the thylacine. Keywords thylacine, representation, photography, human-animal interactions, extinction Introduction References to photography in nineteenth-century zoological publications often stress its difference from previous picture-making traditions; for instance, naturalist Agassiz (1871) commented that “the accuracy of a photographic illustration is of course far beyond that of an engraving or lithograph” (p.