University of Dundee 'No Cricket Strips Here!' an Interview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guests We Are Pleased to Announce That the Following Guests Have Confirmed That They Can Attend

Welcome to this progress report for the Festival. Every year we start with a big task… be better than before. With 28 years of festivals under our belts it’s a big ask, but from the feedback we receive expectations are usually exceeded. The biggest source of disappointment from attendees is that they didn’t hear about the festival earlier and missed out on some fantastic weekends. The upcoming 29th Festival of Fantastic Films will be held over the weekend of October 26– 28 in the Manchester Conference Centre (The Pendulum Hotel) and looks set to be another cracker. So do everyone a favour and spread the word. Guests We are pleased to announce that the following guests have confirmed that they can attend Michael Craig Simon Andreu Aldo Lado Dez Skinn Ray Brady 1 A message from the Festival’s Chairman And so we approach the 29th Festival - a position that none of us who began it all could ever have envisioned. We thought that if it went on for about five years, we would be happy. My biggest regret is that I am the only one of that original formation group who is still actively involved in the organisation. I'm not sure if that's because I am a real survivor or if I just don't like quitting. Each year as we look at putting on another Festival, I think of those people who were there at the outset - Harry Nadler, Dave Trengove, and Tony Edwards, without whom the event wouldn’t be what it is. -

Alan Moore's Miracleman: Harbinger of the Modern Age of Comics

Alan Moore’s Miracleman: Harbinger of the Modern Age of Comics Jeremy Larance Introduction On May 26, 2014, Marvel Comics ran a full-page advertisement in the New York Times for Alan Moore’s Miracleman, Book One: A Dream of Flying, calling the work “the series that redefined comics… in print for the first time in over 20 years.” Such an ad, particularly one of this size, is a rare move for the comic book industry in general but one especially rare for a graphic novel consisting primarily of just four comic books originally published over thirty years before- hand. Of course, it helps that the series’ author is a profitable lumi- nary such as Moore, but the advertisement inexplicably makes no reference to Moore at all. Instead, Marvel uses a blurb from Time to establish the reputation of its “new” re-release: “A must-read for scholars of the genre, and of the comic book medium as a whole.” That line came from an article written by Graeme McMillan, but it is worth noting that McMillan’s full quote from the original article begins with a specific reference to Moore: “[Miracleman] represents, thanks to an erratic publishing schedule that both predated and fol- lowed Moore’s own Watchmen, Moore’s simultaneous first and last words on ‘realism’ in superhero comics—something that makes it a must-read for scholars of the genre, and of the comic book medium as a whole.” Marvel’s excerpt, in other words, leaves out the very thing that McMillan claims is the most important aspect of Miracle- man’s critical reputation as a “missing link” in the study of Moore’s influence on the superhero genre and on the “medium as a whole.” To be fair to Marvel, for reasons that will be explained below, Moore refused to have his name associated with the Miracleman reprints, so the company was legally obligated to leave his name off of all advertisements. -

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore THE INVENTION OF THE GRAPHIC NOVEL: UNDERGROUND COMIX AND CORPORATE AESTHETICS BY SHAWN PATRICK GILMORE DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Michael Rothberg, Chair Professor Cary Nelson Associate Professor James Hansen Associate Professor Stephanie Foote ii Abstract This dissertation explores what I term the invention of the graphic novel, or more specifically, the process by which stories told in comics (or graphic narratives) form became longer, more complex, concerned with deeper themes and symbolism, and formally more coherent, ultimately requiring a new publication format, which came to be known as the graphic novel. This format was invented in fits and starts throughout the twentieth century, and I argue throughout this dissertation that only by examining the nuances of the publishing history of twentieth-century comics can we fully understand the process by which the graphic novel emerged. In particular, I show that previous studies of the history of comics tend to focus on one of two broad genealogies: 1) corporate, commercially-oriented, typically superhero-focused comic books, produced by teams of artists; 2) individually-produced, counter-cultural, typically autobiographical underground comix and their subsequent progeny. In this dissertation, I bring these two genealogies together, demonstrating that we can only truly understand the evolution of comics toward the graphic novel format by considering the movement of artists between these two camps and the works that they produced along the way. -

Judge Dredd: V. 1: the Restricted Files Free

FREE JUDGE DREDD: V. 1: THE RESTRICTED FILES PDF John Wagner,Alan Grant | 320 pages | 15 Feb 2010 | Rebellion | 9781906735333 | English | Oxford, United Kingdom Judge Dredd: The Restricted Files 01 by John Wagner Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Judge Dredd: v. 1: The Restricted Files rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. Preview — Judge Dredd by John Wagner. Alan Grant. Steve Moore. Carlos Ezquerra Illustrator. Mike McMahon Illustrator. Kevin O'Neill Illustrator. Ian Gibson Illustrator. Brian Bolland Illustrator. Collects together forgetten and rare gens from the Thrill-power archives. Readers can experience Dredd strips that haven't been reprinted in over 30 years. This collection of classic strips in a must-read for any comic fan! Get A Copy. Paperbackpages. More Details Original Title. Mega-City One United States. Other Editions 1. Friend Reviews. To see Judge Dredd: v. 1: The Restricted Files your friends thought of this book, please sign up. To ask other readers questions about Judge Dreddplease sign up. Lists with This Book. Community Reviews. Showing Average rating 3. Rating details. More filters. Sort order. Aug 15, Eamonn Murphy rated it liked it. This nice book, much of it in colour, collects Judge Dredd stories from various AD Summer Specials and Annuals between and Being culled from Specials and Annuals it features no long, continuing stories, only short one-offs. -

Crime, Law Enforcement, and Punishment

Shirley Papers 48 Research Materials, Crime Series Inventory Box Folder Folder Title Research Materials Crime, Law Enforcement, and Punishment Capital Punishment 152 1 Newspaper clippings, 1951-1988 2 Newspaper clippings, 1891-1938 3 Newspaper clippings, 1990-1993 4 Newspaper clippings, 1994 5 Newspaper clippings, 1995 6 Newspaper clippings, 1996 7 Newspaper clippings, 1997 153 1 Newspaper clippings, 1998 2 Newspaper clippings, 1999 3 Newspaper clippings, 2000 4 Newspaper clippings, 2001-2002 Crime Cases Arizona 154 1 Cochise County 2 Coconino County 3 Gila County 4 Graham County 5-7 Maricopa County 8 Mohave County 9 Navajo County 10 Pima County 11 Pinal County 12 Santa Cruz County 13 Yavapai County 14 Yuma County Arkansas 155 1 Arkansas County 2 Ashley County 3 Baxter County 4 Benton County 5 Boone County 6 Calhoun County 7 Carroll County 8 Clark County 9 Clay County 10 Cleveland County 11 Columbia County 12 Conway County 13 Craighead County 14 Crawford County 15 Crittendon County 16 Cross County 17 Dallas County 18 Faulkner County 19 Franklin County Shirley Papers 49 Research Materials, Crime Series Inventory Box Folder Folder Title 20 Fulton County 21 Garland County 22 Grant County 23 Greene County 24 Hot Springs County 25 Howard County 26 Independence County 27 Izard County 28 Jackson County 29 Jefferson County 30 Johnson County 31 Lafayette County 32 Lincoln County 33 Little River County 34 Logan County 35 Lonoke County 36 Madison County 37 Marion County 156 1 Miller County 2 Mississippi County 3 Monroe County 4 Montgomery County -

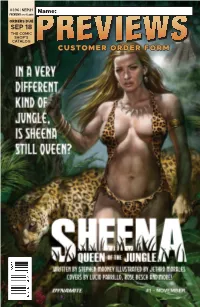

Customer Order Form

#396 | SEP21 PREVIEWS world.com Name: ORDERS DUE SEP 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM Sep21 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 8/5/2021 10:52:51 AM GTM_Previews_ROF.indd 1 8/5/2021 8:54:18 AM PREMIER COMICS NEWBURN #1 IMAGE COMICS 34 A THING CALLED TRUTH #1 IMAGE COMICS 38 JOY OPERATIONS #1 DARK HORSE COMICS 84 HELLBOY: THE BONES OF GIANTS #1 DARK HORSE COMICS 86 SONIC THE HEDGEHOG: IMPOSTER SYNDROME #1 IDW PUBLISHING 114 SHEENA, QUEEN OF THE JUNGLE #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 132 POWER RANGERS UNIVERSE #1 BOOM! STUDIOS 184 HULK #1 MARVEL COMICS MP-4 Sep21 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 8/5/2021 10:52:11 AM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Guillem March’s Laura #1 l ABLAZE The Heathens #1 l AFTERSHOCK COMICS Fathom: The Core #1 l ASPEN COMICS Watch Dogs: Legion #1 l BEHEMOTH ENTERTAINMENT 1 Tuki Volume 1 GN l CARTOON BOOKS Mutiny Magazine #1 l FAIRSQUARE COMICS Lure HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS 1 The Overstreet Guide to Lost Universes SC/HC l GEMSTONE PUBLISHING Carbon & Silicon l MAGNETIC PRESS Petrograd TP l ONI PRESS Dreadnoughts: Breaking Ground TP l REBELLION / 2000AD Doctor Who: Empire of the Wolf #1 l TITAN COMICS Blade Runner 2029 #9 l TITAN COMICS The Man Who Shot Chris Kyle: An American Legend HC l TITAN COMICS Star Trek Explorer Magazine #1 l TITAN COMICS John Severin: Two-Fisted Comic Book Artist HC l TWOMORROWS PUBLISHING The Harbinger #2 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT Lunar Room #1 l VAULT COMICS MANGA 2 My Hero Academia: Ultra Analysis Character Guide SC l VIZ MEDIA Aidalro Illustrations: Toilet-Bound Hanako Kun Ark Book SC l YEN PRESS Rent-A-(Really Shy!)-Girlfriend Volume 1 GN l KODANSHA COMICS Lupin III (Lupin The 3rd): Greatest Heists--The Classic Manga Collection HC l SEVEN SEAS ENTERTAINMENT APPAREL 2 Halloween: “Can’t Kill the Boogeyman” T-Shirt l HORROR Trese Vol. -

Fudge the Elf

1 Fudge The Elf Ken Reid The Laura Maguire collection Published October 2019 All Rights Reserved Sometime in the late nineteen nineties, my daughter Laura, started collecting Fudge books, the creation of the highly individual Ken Reid. The books, the daily strip in 'The Manchester Evening News, had been a part of my childhood. Laura and her brother Adam avidly read the few dog eared volumes I had managed to retain over the years. In 2004 I created a 'Fudge The Elf' website. This brought in many contacts, collectors, individuals trying to find copies of the books, Ken's Son, the illustrator and colourist John Ridgeway, et al. For various reasons I have decided to take the existing website off-line. The PDF faithfully reflects the entire contents of the original website. Should you wish to get in touch with me: [email protected] Best Regards, Peter Maguire, Brussels 2019 2 CONTENTS 4. Ken Reid (1919–1987) 5. Why This Website - Introduction 2004 6. Adventures of Fudge 8. Frolics With Fudge 10. Fudge's Trip To The Moon 12. Fudge And The Dragon 14. Fudge In Bubbleville 16. Fudge In Toffee Town 18. Fudge Turns Detective Savoy Books Editions 20. Fudge And The Dragon 22. Fudge In Bubbleville The Brockhampton Press Ltd 24. The Adventures Of Dilly Duckling Collectors 25. Arthur Gilbert 35. Peter Hansen 36. Anne Wilikinson 37. Les Speakman Colourist And Illustrator 38. John Ridgeway Appendix 39. Ken Reid-The Comic Genius 3 Ken Reid (1919–1987) Ken Reid enjoyed a career as a children's illustrator for more than forty years. -

Springfield, Millburn Join in Memorial Day Parade

COMPLETE OVERSiOOO— Coverage in News and People in Springfield Circulation - - - Read 1 It liTtbe Sun Read the Sun Each Week vni yyiii,KJn: 79 OFFICIAL NEWSPAPER • ' SPRINGFIELD, N7"Jr,~ THURSDAY, MAY 20, 1948 OFFICIAL NEWSPAPER . DOHOUGll OF MOUNTAINSIDE TOWNSHIP OF SPRINGFIELD 6c A COPY, $2.50 BY THE YEAR Full Principal Well Known Bike Rider DiesSchool Aid Tax LISTEN^ WFirsi'mFatarAccident Springfield, Millburn Join Haymond B" Puterbaugh, 33 Dengler. Death was attributed, to For Chisholm years old, of 52 Hudson, street, a fractured skull. For Springfield East- Orange, promlnont amateur Wllliam-H-0'Hern7-23~-of-E«st In Memorial Day Parade bicyclist and president of the Hanover, driver of the auto, ww Olympic Bicycle Roller Club, was arraigned . after the accident be- Totals $10,733 I School Urged instantly killed Sunday at 10 a. m., fore Recorder Spinning on a MUMPS EPIDEMIC Veterans, Scouts, Others to when hi» bicycle swerved into the charge of causing death, with a HERE IN APRIL rear end of an auto on Mountain motors-vehicle. Patrolman Nelson 'avenue, 800-feet south of Shunpike Stiles was the complainant. He Springfield passed through Need Stressed in Taxpayers Saved an epidemic stage of mumps Take Part in Ceremonies ~road;—- \ :• •--•-,—- . pleaded/not guilty and • was re- during April, according to_a Puterbaugh was taken to Over- le"o»ed ~fn—$500— bond for Grand iPlans are.nearing-completion for the annual Spring- Recommendation Large. Sum by report submitted-to-the.-Board look Hospital, Summit, in the Jury action. _..•.•• field-Millburn Memorial Day parade to be held Monday, May -of Health last night by Robert 31, All local participating units will assemble in the area of To Local Board township ambulance by Patrol- First PtttalHy This Year Cigarette Levy D. -

![[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3367/japan-sala-giochi-arcade-1000-miglia-393367.webp)

[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia

SCHEDA NEW PLATINUM PI4 EDITION La seguente lista elenca la maggior parte dei titoli emulati dalla scheda NEW PLATINUM Pi4 (20.000). - I giochi per computer (Amiga, Commodore, Pc, etc) richiedono una tastiera per computer e talvolta un mouse USB da collegare alla console (in quanto tali sistemi funzionavano con mouse e tastiera). - I giochi che richiedono spinner (es. Arkanoid), volanti (giochi di corse), pistole (es. Duck Hunt) potrebbero non essere controllabili con joystick, ma richiedono periferiche ad hoc, al momento non configurabili. - I giochi che richiedono controller analogici (Playstation, Nintendo 64, etc etc) potrebbero non essere controllabili con plance a levetta singola, ma richiedono, appunto, un joypad con analogici (venduto separatamente). - Questo elenco è relativo alla scheda NEW PLATINUM EDITION basata su Raspberry Pi4. - Gli emulatori di sistemi 3D (Playstation, Nintendo64, Dreamcast) e PC (Amiga, Commodore) sono presenti SOLO nella NEW PLATINUM Pi4 e non sulle versioni Pi3 Plus e Gold. - Gli emulatori Atomiswave, Sega Naomi (Virtua Tennis, Virtua Striker, etc.) sono presenti SOLO nelle schede Pi4. - La versione PLUS Pi3B+ emula solo 550 titoli ARCADE, generati casualmente al momento dell'acquisto e non modificabile. Ultimo aggiornamento 2 Settembre 2020 NOME GIOCO EMULATORE 005 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1 On 1 Government [Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 10-Yard Fight SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 18 Holes Pro Golf SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1941: Counter Attack SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1942 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943: The Battle of Midway [Europe] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1944 : The Loop Master [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1945k III SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 19XX : The War Against Destiny [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 4-D Warriors SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 64th. -

The 2000 AD Script Book Free

FREE THE 2000 AD SCRIPT BOOK PDF Pat Mills,John Wagner,Peter Milligan,Al Ewing,Rob Williams,Dan Abnett,Emma Beeby,Gordon Rennie,Ian Edginton,Alan Grant | 192 pages | 03 Nov 2016 | Rebellion | 9781781084670 | English | Oxford, United Kingdom The AD Script Book : Pat Mills : Original scripts by leading comics writers accompanied by the final art, taken from the pages of the world famous AD comic. Featuring original script drafts and the final published artwork for comparison, this is a must have for fans of AD and is an essential purchase for anyone interested in writing comics. Pat Mills is the creator and first editor of AD. He wrote Third World War for Crisis! John Wagner The 2000 AD Script Book been scripting for AD for more years than he cares to remember. The 2000 AD Script Book Ewing is a British novelist and American comic book writer, currently responsible for much of Marvel Comics' Avengers titles. He came to prominence with the 1 UK comic AD and then wrote a sequence of novels for Abaddon, of which the El Sombra books are the most celebrated, before becomiing the regular writer for Doctor Who: The Eleventh Doctor and a leading Marvel writer. He lives in York, England. John Reppion has been writing for thirteen years. He is tired. So tired. Will work for beer. By clicking 'Sign me up' I acknowledge that I have read and agree to the privacy policy and terms of use. Must redeem within 90 days. See full terms and conditions and this month's choices. Tell us what you like and we'll recommend books you'll love. -

Thje Story Jpajpjer Cojljljector N:.��1�:1�:�.4

THJE STORY JPAJPJER COJLJLJECTOR N:.��1�:1�:�.4 ···················································································· ···················································································· Research on Modern "Comics" HERE Is Buying Guidance investigators compared the num on almost everything today ber of beats of a comic on a T and the "comic paper" is window sill, before the paper no exception. The boys of became useless. One of the boys Form 2J at Wakefield Cathedral had the use of a fish and chip Secondary School in England shop, where resistance to grease, have put the modern "comic" salt, and vinegar was measured. under the microscope. Their At first I thought that these findings have been published in tests were something entirely Mitre, the school magazine. new, but on examining some of Five boys of thirteen years did the old comics in my collection the research out of school hours, I see that these, too, have ap and most thoroughly did they parently been used for fly-swat go to work. They nominated as ting, and from the food-stains the best comic one which they on some of them they have also found not only best to read, but been tested as table-cloths! also the best for holding fish and I still have in my possession a chips, for fly-swatting, and for frantic letter from a postal mem fire-lighting! ber of the Northern Section The winning comic-unfortu [Old Boys' Book Club] library nately the name is not given in telling me that his wife had lit the report-took 66 minutes, 38 the fire with a Magnet from the seconds to read, against 9 min Secret Society series. -

Buster Turns Kristin Smart Case Upside-Down!

http://CaliforniaRegister.com SAN LUIS OBISPO - SPECIAL EDITION Volume 3 - Issue 1 JANUARY 15, 2015 PRSRT STD “Congress shall make no law ... **********ECRWSSEDDM**** ECRWSS abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press...” U.S. POSTAGE PAID Residential Customer PISMO BEACH, CA Ratified by Congress: December 15, 1791 PERMIT NO. 99 Buster Turns Kristin Smart Case Upside-Down! Search Dog “Buster” Detects Human Remains Behind Arroyo Grande Home Soil Sample Contains a Human-Specific Chemical, but Sheriff Ignores it All! specific chemical normally found response. The lack of action by the found a woman’s earring. On the The following article is an update in human remains. San Luis Obispo Sheriff’s department following day, Joseph Lassiter while for those who have been following • August 1, 2014, Buster alerts in was disappointing and troublesome. being deposed stated he and his wife the Kristin Smart disappearance. the backyard of 523 E. Branch When Mrs. Smart asked the sheriff were in possession of the earring. Newcomers to the Kristin Smart St., Arroyo Grande. A forensic about it, he dismissed the dog alerts Joseph Lassiter described the earring case are encouraged to first read the scientist and a retired police because Buster was not a “certified” as: hooped with beads and a flat piece entire story at: CaliforniaRegister. search dog. Additionally, Parkinson which connects to the ear, a “little com/kristin-smart/ detective believe human-specific chemicals are present in the soil did not place too much faith in the beaded thing that hangs down.” around the backyard of 529 E. soil-sample analysis either.