“Everything Was in Flames” the Attack on a Displaced Persons Camp in Alindao

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Les Publications À L'occasion Du Centenaire De L'ã©Vangã©Lisation En RéPublique Centrafricaine

Mémoire Spiritaine Volume 1 De l'importance des Ancêtres pour inventer Article 13 l'avenir... April 1995 Les publications à l'occasion du centenaire de l'évangélisation en République Centrafricaine Ghislain de Banville Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/memoire-spiritaine Part of the Catholic Studies Commons Recommended Citation de Banville, G. (2019). Les publications à l'occasion du centenaire de l'évangélisation en République Centrafricaine. Mémoire Spiritaine, 1 (1). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/memoire-spiritaine/vol1/iss1/13 This Chroniques et commentaires is brought to you for free and open access by the Spiritan Collection at Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mémoire Spiritaine by an authorized editor of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. Fondation de Saint-Paul des Rapides, à Bangui, par Mgr Prosper Augouard ( 1894 ). Reproduction d'une carte postale éditée à l'occasion du centenaire. CHRONIQUES ET COMMENTAIRES Mémoire Spiritaine, avril 1995, p. 147 à 150 Les publications à Foccasion du centenaire de révangélisation en R.C.A. Ghislain de Banville* 13 février 1894 Fondation de la mission Saint-Paul des Rapides, à Bangui. 2 novembre 1894 Fondation de la mission Sainte-Famille des Banziris, à Ouadda 1^' ( transférée le février 1895 à Bessou ). Ces deux créations de stations missionnaires par Mgr Prosper Augouard, vicaire apostolique à Brazzaville, marquent le début de l'évangélisation en Centrafrique. De l'Epiphanie 1994 à l'Epiphanie 1995, l'Éghse cathoHque a célébré l'événement. Sur ces festivités, préparées depuis janvier 1993, il cette chronique est seulement de y aurait beaucoup à dire ; mais l'objet de faire le point sur les pubhcations mises à la disposition des chrétiens à l'occa- sion de ce centenaire. -

472,864 25% USD 243.8 Million

CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC SITUATION UNHCR REGIONAL UPDATE 65 1 – 29 February 2016 HIGHLIGHTS KEY FIGURES . In the Central African Republic, UNHCR finalized the IDP registration 472,864 exercise in the capital city Bangui and provided emergency assistance to Central African refugees in displaced families affected by multiple fire outbreaks in IDP sites; Cameroon, Chad, DRC and Congo . UNHCR launched a youth community project in Chad, an initiative providing young Central African refugees with the opportunity to develop their own projects; . The biometric registration of urban refugees in Cameroon is completed in the 25% capital Yaoundé and ongoing in the city of Douala; IDPs in CAR located in the capital . In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, UNHCR registered 4,376 Central Bangui African refugees living on several islands in the Ubangi River; . Refugees benefit from a country-wide vaccination campaign in the Republic of the Congo. The persistent dire funding situation of UNHCR’s operations in all countries is worrisome and additional contributions are required immediately to meet FUNDING urgent protection and humanitarian needs. USD 243.8 million required for the situation in 2016 917,131 persons of concern Funded 0.2% IDPs in CAR 435,165 Gap Refugees in 270,562 99.8% Cameroon Refugees in DRC 108,107 PRIORITIES Refugees in Chad 65,961 . CAR: Reinforce protection mechanisms from sexual exploitation and abuse and strengthen coordination with Refugees in Congo 28,234 relevant actors. Cameroon: Continue biometric registration; strengthen the WASH response in all refugee sites. Chad: Strengthen advocacy to improve refugees’ access to arable land; promote refugee’s self-sufficiency. -

Central African Republic Emergency Situation UNHCR Regional Bureau for Africa As of 26 September 2014

Central African Republic Emergency Situation UNHCR Regional Bureau for Africa as of 26 September 2014 N'Djamena UNHCR Representation NIGERIA UNHCR Sub-Office Kerfi SUDAN UNHCR Field Office Bir Nahal Maroua UNHCR Field Unit CHAD Refugee Sites 18,000 Haraze Town/Village of interest Birao Instability area Moyo VAKAGA CAR refugees since 1 Dec 2013 Sarh Number of IDPs Moundou Doba Entry points Belom Ndele Dosseye Sam Ouandja Amboko Sido Maro Gondje Moyen Sido BAMINGUI- Goré Kabo Bitoye BANGORAN Bekoninga NANA- Yamba Markounda Batangafo HAUTE-KOTTO Borgop Bocaranga GRIBIZI Paoua OUHAM 487,580 Ngam CAMEROON OUHAM Nana Bakassa Kaga Bandoro Ngaoui SOUTH SUDAN Meiganga PENDÉ Gbatoua Ngodole Bouca OUAKA Bozoum Bossangoa Total population Garoua Boulai Bambari HAUT- Sibut of CAR refugees Bouar MBOMOU GadoNANA- Grimari Cameroon 236,685 Betare Oya Yaloké Bossembélé MBOMOU MAMBÉRÉ KÉMO Zemio Chad 95,326 Damara DR Congo 66,881 Carnot Boali BASSE- Bertoua Timangolo Gbiti MAMBÉRÉ- OMBELLA Congo 19,556 LOBAYE Bangui KOTTO KADÉÏ M'POKO Mbobayi Total 418,448 Batouri Lolo Kentzou Berbérati Boda Zongo Ango Mbilé Yaoundé Gamboula Mbaiki Mole Gbadolite Gari Gombo Inke Yakoma Mboti Yokadouma Boyabu Nola Batalimo 130,200 Libenge 62,580 IDPs Mboy in Bangui SANGHA- Enyelle 22,214 MBAÉRÉ Betou Creation date: 26 Sep 2014 Batanga Sources: UNCS, SIGCAF, UNHCR 9,664 Feedback: [email protected] Impfondo Filename: caf_reference_131216 DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC The boundaries and names shown and the OF THE CONGO designations used on this map do not imply GABON official endorsement or acceptance by the United CONGO Nations. Final boundary between the Republic of Sudan and the Republic of South Sudan has not yet been determined. -

Central African Republic Humanitarian Situation Report

Central African Republic Humanitarian Situation Report © UNICEFCAR/2018/Jonnaert September 2018 SITUATION IN NUMBERS Highlights 1.3 million # of children in need of humanitarian assistance - On 17 September, the school year was officially launched by the President in Bangui. UNICEF technically and financially supported 2.5 million the Ministry of Education (MoE) in the implementation of the # of people in need (OCHA, June 2018) national ‘Back to School’ mass communication campaign in all 8 Academic Inspections. The Education Cluster estimates that 280,000 621,035 school-age children were displaced, including 116,000 who had # of Internally displaced persons (OCHA, August 2018) dropped out of school Outside CAR - The Rapid Response Mechanism (RRM) hit a record month, with partners ensuring 10 interventions across crisis-affected areas, 572, 984 reaching 38,640 children and family members with NFI kits, and # of registered CAR refugees 59,443 with WASH services (UNHCR, August 2018) - In September, 19 violent incidents against humanitarian actors were 2018 UNICEF Appeal recorded, including UNICEF partners, leading to interruptions of assistance, just as dozens of thousands of new IDPs fleeing violence US$ 56.5 million reached Bria Sector/Cluster UNICEF Funding status* (US$) Key Programme Indicators Cluster Cumulative UNICEF Cumulative Target results (#) Target results (#) WASH: Number of affected people Funding gap : Funds provided with access to improved 900,000 633,795 600,000 82,140 $32.4M (57%) received: sources of water as per agreed $24.6M standards Education: Number of Children (boys and girls 3-17yrs) in areas 94,400 79,741 85,000 69,719 affected by crisis accessing education Required: Health: Number of children under 5 $56.5M in IDP sites and enclaves with access N/A 500,000 13,053 to essential health services and medicines. -

Interagency Assessment Report

AA SS SS EE SS SS MM EE NN TT RR EE PP OO RR TT Clearing of site for returning refugees from Chad, Moyenne Sido, 18 Feb. 2008 Moyenne Sido Sous-Prefecture, Ouham 17 – 19 February 2008 Contents 1. Introduction & Context………………………………………………………………. 2. Participants & Itinerary ……………………………………………………………... 3. Key Findings …………………………………………………. ……………………. 4. Assessment Methodology………………………………………………………..... 5. Sectoral Findings: NFI’s, Health & Nutrition, WASH, Protection, Education ………………………. 6. Recommendations & Proposed Response…………. …………….................... 2 Introduction & Context The sous prefecture of Moyenne Sido came into creation in March 2007, making it the newest sous- prefecture in the country. As a result, it has a little civil structure and has not received any major investment from the governmental level, and currently there is only the Mayor who is struggling to meet the needs of both the returnees and the host population, the latter is estimated at 17,000 persons. During the course of the visit, he was followed by several groups of elderly men (heads of families) who were requesting food from him, or any other form of assistance. The Mayor was distressed that neither the governmental authorities nor humanitarian agencies have yet been able to provide him with advice or assistance. The returnees are mainly Central African Republic citizens who fled to southern Chad after the coup in 2003. Since then, they have been residing at Yarounga refugee camp in Chad. Nine months ago, they received seeds from an NGO called Africa Concern, which they were supposed to plant and therefore be able to provide food for themselves. However, the returnees have consistently stated that the land they were set aside for farming was dry and arid, and they were unable to grow their crops there. -

ACTIVE USG HUMANITARIAN PROGRAMS in CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC Last Updated 11/21/14

ACTIVE USG HUMANITARIAN PROGRAMS IN CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC Last Updated 11/21/14 COUNTRYWIDE PROGRAM KEY FAO USAID/OFDA USAID/FFP SUDAN State/PRM IFRC VAKAGA Agriculture and Food Security IOM Am Dafok IMC Birao Economic Recovery and Market NetHope CHAD Systems OCHA Evacuation and On-arrival Assistance Food Assistance UNDSS BAMINGUI-BANGORAN VAKAGA Food Vouchers UNHAS DRC Health UNICEF OUHAM Garba Humanitarian Air Service WFP ACF HAUTE-KOTTO Ouanda Djalle Humanitarian Coordination IMC WHO CRS and Information Management UNICEF DRC Locally and Regionally Procured Food Ndele Ouandjia WFP IMC Logistics and Relief Commodities ICRC Mentor BAMINGUI-BANGORAN Ouadda Multi-Sector Assistance Kadja IOM Nutrition UNHCR Protection Bamingui HAUTE-KOTTO WFP NANA- Boulouba Refugee Assistance Paoua Batangafo GRIBIZI OUHAM-PENDÉ Shelter and Settlements Kaga Bandoro ACTED Bocaranga OUHAM Yangalia Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene OUAKA DRC OUHAM- Bossangoa IMC Bria Yalinga IRC PENDÉ Bouca HAUT-MBOMOU SOUTH Bozoum Dekoa Mentor SUDAN KÉMO Ippy Djema Bouar NRC OUAKA Baboua Grimari Sibut Bakouma NANA- Bambari MAMBÉRÉ Baoro Bogangolo MBOMOU KÉMO Obo NANA-MAMBÉRÉ Yaloke Bossembele Mingala SC/US BASSE- Rafai OMBELLA OMBELLA M’POKO Kouango Carnot Djomo KOTTO Zemio HAUT-MBOMOU M'POKO World Vision Bangassou MBOMOU SC/US N MAMBÉRÉ-KADEÏ Mobaye Berberati Boda Bimbo Bangui Mercy Corps Gamboula Ouango OO LOBAYE BANGUI R Soso MAMBÉRÉ-KADEÏ Mbaiki ACTED NRC Nola Regional Assistance to People Fleeing CAR SANGHA- LOBAYE CAME MBAÉRÉ Tearfund DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC WFP LWF OF THE CONGO CARE Mentor CSSI UNFPA INFORMA IC TI PH O REPUBLIC A N R U IMC UNHCR G N O I T E 0 50 100 mi G OF THE IOM UNICEF U S A A D CONGO 0 50 100 150 km I F IRC WHO D O / D C H A /. -

The Central African Republic Diamond Database—A Geodatabase of Archival Diamond Occurrences and Areas of Recent Artisanal and Small-Scale Diamond Mining

Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Agency for International Development under the auspices of the U.S. Department of State The Central African Republic Diamond Database—A Geodatabase of Archival Diamond Occurrences and Areas of Recent Artisanal and Small-Scale Diamond Mining Open-File Report 2018–1088 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover. The main road west of Bambari toward Bria and the Mouka-Ouadda plateau, Central African Republic, 2006. Photograph by Peter Chirico, U.S. Geological Survey. The Central African Republic Diamond Database—A Geodatabase of Archival Diamond Occurrences and Areas of Recent Artisanal and Small-Scale Diamond Mining By Jessica D. DeWitt, Peter G. Chirico, Sarah E. Bergstresser, and Inga E. Clark Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Agency for International Development under the auspices of the U.S. Department of State Open-File Report 2018–1088 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior RYAN K. ZINKE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey James F. Reilly II, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2018 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit https://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit https://store.usgs.gov. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materials as noted in the text. -

MSF: Unprotected: Summary of Internal Review on the October 31St Events in Batangafo, Central African Republic

MSF February 2019 Unprotected Summary of internal review on the October 31st events in Batangafo, Central African Republic Unprotected. Summary of internal review on the October 31st events in Batangafo, Central African Republic. February 2019 The Centre for Applied Reflection on Humanitarian Practice (ARHP) documents and reflects upon the operational challenges and dilemmas faced by the field teams of the MSF Operational Centre Barcelona (MSF OCBA). This report is available at the ARHP website: https://arhp.msf.es © MSF C/ Nou de la Rambla, 26 08001 Barcelona Spain Pictures by Helena Cardellach. FRONT-PAGE PICTURE: IDP site burned, November 1st 2018. Batangafo, Central African Republic. Contents 5 Methodology 7 Executive summary 9 Brief chronology of events 10 Violence-related background of Central African Republic and Batangafo 15 Description and analysis of events 20 Consequences of violence 23 The humanitarian response 25 A hospital at the centre of the power struggle 28 Civilians UN-protected? 29 Conclusions 31 Asks 32 MSF in CAR and Batangafo 3 MSF | Unprotected. Summary of internal review on the October 31st events in Batangafo (CAR) Acronyms used AB Antibalaka CAR Central African Republic DRC Danish Refugee Council ES Ex Séléka FPRC Popular Front for the Rebirth of CAR GoCAR Government of CAR HC Humanitarian Coordinator (UN) IDP Internal Displaced People IHL International Humanitarian Law MINUSCA UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in CAR MPC Central African Patriotic Movement TOB (UN) Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs UN Temporary Operational Base UNOCHA United Nations UNSC UN Security Council 4 MSF | Unprotected. Summary of internal review on the October 31st events in Batangafo (CAR) Methodology This report has been elaborated by the MSF’s Centre for Applied Research on Humanitarian Practice (ARHP) between November 2018 and early January 2019. -

Central African Rep.: Sub-Prefectures 09 Jun 2015

Central African Rep.: Sub-Prefectures 09 Jun 2015 NIGERIA Maroua SUDAN Birao Birao Abyei REP. OF Garoua CHAD Ouanda-Djallé Ouanda-Djalle Ndélé Ndele Ouadda Ouadda Kabo Bamingui SOUTH Markounda Kabo Ngaounday Bamingui SUDAN Markounda CAMEROON Djakon Mbodo Dompta Batangafo Yalinga Goundjel Ndip Ngaoundaye Boguila Batangafo Belel Yamba Paoua Nangha Kaga-Bandoro Digou Bocaranga Nana-Bakassa Borgop Yarmbang Boguila Mbrès Nyambaka Adamou Djohong Ouro-Adde Koui Nana-Bakassa Kaga-Bandoro Dakere Babongo Ngaoui Koui Mboula Mbarang Fada Djohong Garga Pela Bocaranga MbrÞs Bria Djéma Ngam Bigoro Garga Bria Meiganga Alhamdou Bouca Bakala Ippy Yalinga Simi Libona Ngazi Meidougou Bagodo Bozoum Dekoa Goro Ippy Dir Kounde Gadi Lokoti Bozoum Bouca Gbatoua Gbatoua Bakala Foulbe Dékoa Godole Mala Mbale Bossangoa Djema Bindiba Dang Mbonga Bouar Gado Bossemtélé Rafai Patou Garoua-BoulaiBadzere Baboua Bouar Mborguene Baoro Sibut Grimari Bambari Bakouma Yokosire Baboua Bossemptele Sibut Grimari Betare Mombal Bogangolo Bambari Ndokayo Nandoungue Yaloké Bakouma Oya Zémio Sodenou Zembe Baoro Bogangolo Obo Bambouti Ndanga Abba Yaloke Obo Borongo Bossembele Ndjoukou Bambouti Woumbou Mingala Gandima Garga Abba Bossembélé Djoukou Guiwa Sarali Ouli Tocktoyo Mingala Kouango Alindao Yangamo Carnot Damara Kouango Bangassou Rafa´ Zemio Zémio Samba Kette Gadzi Boali Damara Alindao Roma Carnot Boulembe Mboumama Bedobo Amada-Gaza Gadzi Bangassou Adinkol Boubara Amada-Gaza Boganangone Boali Gambo Mandjou Boganangone Kembe Gbakim Gamboula Zangba Gambo Belebina Bombe Kembé Ouango -

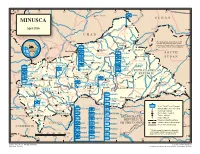

MINUSCA T a Ou M L B U a a O L H R a R S H Birao E a L April 2016 R B Al Fifi 'A 10 H R 10 ° a a ° B B C H a VAKAGA R I CHAD

14° 16° 18° 20° 22° 24° 26° ZAMBIA Am Timan é Aoukal SUDAN MINUSCA t a ou m l B u a a O l h a r r S h Birao e a l April 2016 r B Al Fifi 'A 10 h r 10 ° a a ° B b C h a VAKAGA r i CHAD Sarh Garba The boundaries and names shown ouk ahr A Ouanda and the designations used on this B Djallé map do not imply official endorsement Doba HQ Sector Center or acceptance by the United Nations. CENTRAL AFRICAN Sam Ouandja Ndélé K REPUBLIC Maïkouma PAKISTAN o t t SOUTH BAMINGUI HQ Sector East o BANGORAN 8 BANGLADESH Kaouadja 8° ° SUDAN Goré i MOROCCO u a g n i n i Kabo n BANGLADESH i V i u HAUTE-KOTTO b b g BENIN i Markounda i Bamingui n r r i Sector G Batangafo G PAKISTAN m Paoua a CAMBODIA HQ Sector West B EAST CAMEROON Kaga Bandoro Yangalia RWANDA CENTRAL AFRICAN BANGLADESH m a NANA Mbrès h OUAKA REPUBLIC OUHAM u GRÉBIZI HAUT- O ka Bria Yalinga Bossangoa o NIGER -PENDÉ a k MBOMOU Bouca u n Dékoa MAURITANIA i O h Bozoum C FPU CAMEROON 1 OUHAM Ippy i 6 BURUNDI Sector r Djéma 6 ° a ° Bambari b ra Bouar CENTER M Ouar Baoro Sector Sibut Baboua Grimari Bakouma NANA-MAMBÉRÉ KÉMO- BASSE MBOMOU M WEST Obo a Yaloke KOTTO m Bossembélé GRIBINGUI M b angúi bo er ub FPU BURUNDI 1 mo e OMBELLA-MPOKOYaloke Zémio u O Rafaï Boali Kouango Carnot L Bangassou o FPU BURUNDI 2 MAMBÉRÉ b a y -KADEI CONGO e Bangui Boda FPU CAMEROON 2 Berberati Ouango JTB Joint Task Force Bangui LOBAYE i Gamboula FORCE HQ FPU CONGO Miltary Observer Position 4 Kade HQ EGYPT 4° ° Mbaïki Uele National Capital SANGHA Bondo Mongoumba JTB INDONESIA FPU MAURITANIA Préfecture Capital Yokadouma Tomori Nola Town, Village DEMOCRATICDEMOCRATIC Major Airport MBAÉRÉ UNPOL PAKISTAN PSU RWANDA REPUBLICREPUBLIC International Boundary Salo i Titule g Undetermined Boundary* CONGO n EGYPT PERU OFOF THE THE CONGO CONGO a FPU RWANDA 1 a Préfecture Boundary h b g CAMEROON U Buta n GABON SENEGAL a gala FPU RWANDA 2 S n o M * Final boundary between the Republic RWANDA SERBIA Bumba of the Sudan and the Republic of South 0 50 100 150 200 250 km FPU SENEGAL Sudan has not yet been determined. -

Central African Republic ECHO FACTSHEET

Central African Republic ECHO FACTSHEET shortage Facts & Figures Number of internally displaced (UNHCR): over 450 000, including over 48 000 in the capital Bangui Number of Central African refugees (UNHCR): about 463 500 in neighbouring countries 2.7 million people are in need of humanitarian assistance Around 2.5 million people are food insecure 2.4 million children are affected by the crisis (UNICEF) Other data Population: 4.6 million people Key messages HDI ranking: 185 of 187 countries (UNDP) The humanitarian situation in the Central African Republic (CAR) remains extremely serious over two years after the current crisis erupted in December 2013. Some 2.7 million European Commission humanitarian aid since people – or more than half of the population – are in need of December 2013: humanitarian assistance. 2.4 million children are affected by EUR 103.5million (in addition to €26 million for the crisis, according to UNICEF. Central African refugees in neighbouring countries) The situation has recently worsened after fighting broke out between rival groups in the capital Bangui at the end of EU humanitarian September 2015. It led to at least 75 deaths, more than 400 assistance (European Commission and EU injured and over 20 000 newly displaced. In the last months Member States) since of 2015, violent incidents have continued in Bangui and 2014: spread to the provinces (Batangafo, Bambari). Over € 255 million Humanitarian needs are on the rise, but regular fighting and access constraints complicate aid organisations' work and Humanitarian Aid and access to people in need. Civil Protection B-1049 Brussels, Belgium With over €255 million provided since 2014, the European * Sources: UNHCR; UNDP, ECHO/EDRIS Tel.: (+32 2) 295 44 00 Union is the largest donor of humanitarian assistance to CAR. -

Bulletin 4: Février 2021

Perceptions d’informateurs clés sur la COVID-19: République Centrafricaine Bulletin 4: Février 2021 Introduction Ippy (2) En février 2021, Ground Truth Solutions (GTS) 1 Chef d’association de Bria (6) femmes 1 Enseignant a mené des enquêtes téléphoniques auprès de 1 Président 2 Chefs religieux Bambari (6) d’association de jeunes 1 Transporteur 35 informateurs clés au sein de six localités de la 1 Membre d’une ONG locale 2 Cultivateurs Paoua (8) 1 Travailleur social République Centrafricaine. Le but de cette enquête 1 Chef de communauté 2 Agents de santé 2 Chefs de quartier/ est de comprendre les perceptions de ces membres 1 Commerçant groupe 1 Membre d’une ONG 1 Commerçant clés des communautés affectées sur : 1) le partage locale d’information, 2) le respect des gestes barrières par 4 Travailleurs sociaux les membres de leurs communautés, 3) l’impact socio- économique de la COVID-19 et 4) la vaccination contre la COVID-19. Les données récoltées avec le soutien du Conseil Danois pour les Réfugiés (DRC) permettront d’informer les acteurs humanitaires et d’orienter la réponse humanitaire selon ces perceptions. Sélection des localités À la suite de consultations avec les acteurs humanitaires, Alindao (2) 2 Chefs de groupe de les informateurs clés ont été sélectionnés au sein des six Bangui (11) retournés 1 Agent de santé villes suivantes : Paoua, Bangui, Ippy, Bambari, Bria et 2 Chefs de quartier / groupe Alindao. 1 Commerçant 4 Maires d’arrondissement / sous-commune Localités ciblées 1 Travailleur social Préfectures Les villes ont été sélectionnés selon les critères 1 Transporteur 1 Membre d’une ONG locale Source: Ground Truth Solutions, 2021 suivants : 1.