South Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nineteenth-Century Lunatic Asylums in South Australia and Tasmania (1830-1883)

AUSTRALASIAN HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY, 19,2001 Convicts and the Free: Nineteenth-century lunatic asylums in South Australia and Tasmania (1830-1883) SUSAN PIDDOCK While most ofus are familiar with the idea ofthe lunatic asylum, few people realise that lunatic asylums were intended to be curative places where the insane were return to sanity. In the early nineteenth century a new treatment regime that emphasised the moral management of the insane person in the appropriate environment became popular. This environment was to be provided in the new lunatic asylums being built. This article looks at what this moral environment was and then considers it in the context ofthe provisions made for the insane in two colonies: South Australia and Tasmania. These colonies had totally different backgrounds, one as a colony offree settlers and the other as a convict colony. The continuing use ofnineteenth-century lunatic asylums as modern mental hospitals means that alternative approaches to the traditional approaches ofarchaeology have to be considered, and this article discusses documentary archaeology as one possibility. INTRODUCTION and Australia. In this paper a part of this study is highlighted, that being the provision of lunatic asylums in two colonies of While lunacy and the lunatic asylum are often the subject of Australia: South Australia and Tasmania. The first a colony academic research, little attention has been focused on the that prided itself on the lack of convicts within its society, and asylums themselves, as built environments in which the insane the second a colony which received convicts through the were to be bought back to sanity and returned to society. -

SA Climate Ready Climate Projections for South Australia

South East SA Climate Ready Climate projections for South Australia This document provides a summary of rainfall The region and temperature (maximum and minimum) information for the South East (SE) Natural Resources The SE NRM region (from the Management (NRM) region generated using the northern Coorong and Tatiara districts latest group of international global climate models. to the coast in the south and west, Information in this document is based on a more and Victoria to the east) has wet, cool detailed regional projections report available winters and dry, mild-hot summers; at www.goyderinstitute.org. with increasing rainfall from north to south; coastal zones are dominated by Climate projections at a glance winter rainfall, whilst more summer rain is experienced in inland areas. The future climate of the SE NRM region will be drier and hotter, though the amount of global action on decreasing greenhouse The SA Climate Ready project gas emissions will influence the speed and severity of change. The Goyder Institute is a partnership between the South Decreases in rainfall are projected for all seasons, Australian Government through the Department of Environment, with the greatest decreases in spring. Water and Natural Resources, CSIRO, Flinders University, Average temperatures (maximum and minimum) are University of Adelaide, and the University of South Australia. projected to increase for all seasons. Slightly larger increases In 2011, the Goyder Institute commenced SA Climate Ready, in maximum temperature occur for the spring season. a project to develop climate projections for South Australia. The resulting information provides a common platform on which Government, business and the community can By the end of the 21st century develop solutions to climate change adaptation challenges. -

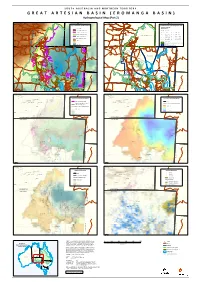

GREAT ARTESIAN BASIN Responsibility to Any Person Using the Information Or Advice Contained Herein

S O U T H A U S T R A L I A A N D N O R T H E R N T E R R I T O R Y G R E A T A R T E S I A N B A S I N ( E RNturiyNaturiyaO M A N G A B A S I N ) Pmara JutPumntaara Jutunta YuenduYmuuendumuYuelamu " " Y"uelamu Hydrogeological Map (Part " 2) Nyirri"pi " " Papunya Papunya ! Mount Liebig " Mount Liebig " " " Haasts Bluff Haasts Bluff ! " Ground Elevation & Aquifer Conditions " Groundwater Salinity & Management Zones ! ! !! GAB Wells and Springs Amoonguna ! Amoonguna " GAB Spring " ! ! ! Salinity (μ S/cm) Hermannsburg Hermannsburg ! " " ! Areyonga GAB Spring Exclusion Zone Areyonga ! Well D Spring " Wallace Rockhole Santa Teresa " Wallace Rockhole Santa Teresa " " " " Extent of Saturated Aquifer ! D 1 - 500 ! D 5001 - 7000 Extent of Confined Aquifer ! D 501 - 1000 ! D 7001 - 10000 Titjikala Titjikala " " NT GAB Management Zone ! D ! Extent of Artesian Water 1001 - 1500 D 10001 - 25000 ! D ! Land Surface Elevation (m AHD) 1501 - 2000 D 25001 - 50000 Imanpa Imanpa ! " " ! ! D 2001 - 3000 ! ! 50001 - 100000 High : 1515 ! Mutitjulu Mutitjulu ! ! D " " ! 3001 - 5000 ! ! ! Finke Finke ! ! ! " !"!!! ! Northern Territory GAB Water Control District ! ! ! Low : -15 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! FNWAP Management Zone NORTHERN TERRITORY Birdsville NORTHERN TERRITORY ! ! ! Birdsville " ! ! ! " ! ! SOUTH AUSTRALIA SOUTH AUSTRALIA ! ! ! ! ! ! !!!!!!! !!!! D !! D !!! DD ! DD ! !D ! ! DD !! D !! !D !! D !! D ! D ! D ! D ! D ! !! D ! D ! D ! D ! DDDD ! Western D !! ! ! ! ! Recharge Zone ! ! ! ! ! ! D D ! ! ! ! ! ! N N ! ! A A ! L L ! ! ! ! S S ! ! N N ! ! Western Zone E -

European Discovery and South Australian Administration of the Northern Territory

3 Prior to 1911: European discovery and South Australian administration of the Northern Territory The first of five time periods that will be used to structure this account of the development and deployment of vocational education and training in the Northern Territory covers the era when European explorers initially intruded upon the ancient Aboriginal tribal lands and culminates with the colony of South Australia gaining control of the jurisdiction. Great Britain took possession of the northern Australian coastline in 1824 when Captain Bremer declared this section of the continent as part of New South Wales. While there were several abortive attempts to establish settlements along the tropical north coast, the climate and isolation provided insurmountable difficulties for the would-be residents. Similarly, the arid southern portion of this territory proved to be inhospitable and difficult to settle. As part of an ongoing project of establishing the borders of the Australian colonies, the Northern Territory became physically separated from New South Wales when the Colonial Office of Great Britain gave control of the jurisdiction to the Government of the Colony of South Australia in 1863 (The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia 1974, p. 83) following the first non-Indigenous south to north crossing of the continent by the South Australian-based explorer John McDouall Stuart in the previous year. 35 VocatioNAL EducatioN ANd TRAiNiNg On the political front, in 1888 South Australia designated the Northern Territory as a single electoral district returning two members to its Legislative Assembly and gave representation in the Upper House in Adelaide. Full adult suffrage was extended by South Australia to all Northern Territory white residents in 1890 that demonstrated an explicit and purposeful disenfranchisement of the much more numerous Asian and Aboriginal populations. -

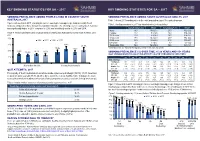

Key Smoking Statistics for Sa – 2017 Key Smoking Statistics for Sa – 2017

KEY SMOKING STATISTICS FOR SA – 2017 KEY SMOKING STATISTICS FOR SA – 2017 SMOKING PREVALENCE AMONG PEOPLE LIVING IN COUNTRY SOUTH SMOKING PREVALENCE AMONG SOUTH AUSTRALIAN ADULTS, 2017 AUSTRALIA, 2017 Table 1 shows 2017 smoking rates in the adult population (aged 15+) and sub-groups. Figure 4 shows that in 2017, smoking prevalence was higher among people living in country South Table 1: Smoking prevalence in 2017 (age standardised to 2006 population) Australia compared to those living in metropolitan Adelaide. The smoking rate for country South Australia was significantly higher in 2017 compared to 2016 and statistically similar to 2015 and 2014. Daily Smokers (%) 95%CI All smokers^ (%) 95%CI Males 18.0 15.6-20.4 20.7 18.2-23.2 Figure 4: Smoking prevalence (CI) for people living and metropolitan Adelaide and country South Australia, 2015- Females 10.7 8.8-12.6 12.4 10.4-14.4 2017 15-29 years 11.4 8.4-14.4 14.7 11.4-18.0 40% 30-44 years 17.5 14.2-20.8 20.7 17.2-24.2 2014 2015 2016 2017 45-59 years 20.3 16.8-23.8 21.5 17.9-25.1 60+ years 7.5 5.4-9.6 8.7 6.5-10.9 30% 23.4% 21.8% Total adults (15+) 14.3 12.8-15.8 16.5 14.9-18.1 17.9% 17.2% ^ Defined as those who reported smoking daily, weekly or less often than weekly 20% 14.2% 12.8% 14.0% 13.5% SMOKING PREVALENCE (%) OVER TIME, 15-29 YEARS AND 15+ YEARS (AGE STANDARDISED TO 2006 POPULATION TO ALLOW COMPARISON OVER TIME) 10% 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Daily smoking 15-29 years 18.1 15.8 17.3 13.6 14.6 14.4 9.9 11.6 10.5 11.4 0% (95% CI) (3.4) (3.2) (3.2) (3.0) (3.1) (3.1) (2.7) (2.8) (2.7) (3.0) Metropolitan Adelaide Country South Australia Adults (15+) 17.4 17.7 17.2 15.2 14.4 16.2 12.8 13.6 12.9 14.3 (95% CI) (1.7) (1.6) (1.6) (1.5) (1.5) (1.6) (1.5) (1.5) (1.4) (1.5) QUIT ATTEMPTS, 2017 All smoking The majority of South Australian smokers have made a previous quit attempt (74.9%); 35.9% have tried 15-29 years 23.4 21.6 22.9 17.6 18.2 19.5 14.8 16.9 12.3 14.7 to quit in the past year and 55.3% intend to try to quit in the next six months. -

Governance in the Early Colony

GOVERNANCE IN THE EARLY COLONY The History Trust of South Australia HISTORY TRUST OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA CENTRE OF DEMOCRACY developed this education resource using The History Trust of South Australia operates The Centre of Democracy is a collaboration the expertise, collections and resources three museums - the Migration Museum, between the History Trust of South Australia of the History Trust of South Australia, the National Motor Museum and the South and the State Library of South Australia. It is its museums and partners. Our learning Australian Maritime Museum, along with supported by the South Australian Government. programs bring to life the stories, the Centre of Democracy managed in Its vibrant program of education, public, objects and people that make up South collaboration with the State Library of South and online programs engage and inform Australia’s rich and vibrant history. Australia. The History Trust’s role is to visitors about the ideas behind democracy, encourage current and future generations political participation and citizenship. The of South Australians to discover this state’s gallery features state treasures from History rich, relevant and fascinating past through Trust and State Library collections, as well as its public programs and museums including items on loan from State Records of South the Migration Museum, the South Australian Australia, the Art Gallery of South Australia, Maritime Museum, the National Motor the Courts Authority, Parliament House, Museum and the Centre of Democracy. Government House and private lenders. history.sa.gov.au centreofdemocracy.sa.gov.au Torrens Parade Ground, Victoria Dr, Adelaide Institute Building, Kintore Ave, Adelaide (08) 8203 9888 (08) 8203 9888 GOVERNANCE IN THE EARLY COLONY AN EDUCATION RESOURCE FOR SECONDARY & SENIOR TEACHERS CONTENTS USING THIS RESOURCE KEY INQUIRY QUESTIONS 02 THE PROVINCE OF This resource is intended to be used in • How have laws affected the lives of SOUTH AUSTRALIA conjunction with three videos produced by people, past and present? the History Trust. -

South Australia's Time Zone

South Australia’s time zone Frequently asked questions Community engagement on South Australia’s time zone 1. What time zone are we currently on? A change to UCT + 10 would mean that the sun would rise and set half an hour later, by the clock, than at present. South Australia’s time zone is 9.5 hours ahead of Coordinated Some people argue that this could have significant negative Universal Time (UTC + 9.5) – the same as the Northern Territory. impacts on the farming sector and social wellbeing, including the safety of children waiting at bus stops in the South Australia is one of only seven places in the world dark, particularly on the West Coast where sunrise times with a half-hour reference point against UTC. are already later than in eastern parts of the state. But Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria, Tasmania and the others speak about the benefits of having an additional 30 Australian Capital Territory all have a time zone of UTC + 10. minutes of sunlight at the end of the day all year round, Western Australia has a time zone of UTC + 8. i.e. for exercise, eating out and heading for the beach. 2. What are the options open for discussion 4. What are some of the impacts for changing South Australia’s time zone? for changing our time zone to be closer to Western Australia? The main options in comments and submissions received to date in the community engagement process are: A change to UCT + 9 would align South Australia • align with the eastern states (UTC + 10) more closely to the same time zone as major trading partners in Asia, such as Japan and Korea (both UCT • move closer to Western Australian time (for example, UTC + 9) + 9) and China, Singapore and Malaysia (UCT + 8). -

South Australia & Northern Territory

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd South Australia & Northern Territory Darwin & the Top End (p142) Uluru & Outback Northern Territory (p179) Outback South Australia (p129) Western South Australia (p120) Barossa Valley & Southeastern South Australia Adelaide (p99) & Around (p52) Anthony Ham & Charles Rawlings-Way PLAN YOUR TRIP ON THE ROAD Welcome to ADELAIDE & Barmera & Around . .. 111 SA & NT . 4 AROUND . 52 Loxton . 112 SA & NT Map . 6 Adelaide . 53 Berri . 113 SA & NT’s Top 12 . .. 8 Adelaide Hills . 76 Renmark & Paringa . 113 Need to Know . 16 Hahndorf . 77 Limestone Coast . 114 First Time . .18 Stirling Area . 78 Robe . 115 Meningie & If You Like . 20 Gumeracha, Birdwood & Lobethal . 80 Coorong National Park . 116 Month by Month . 24 Mt Barker . 81 Mount Gambier . 117 Itineraries . 28 Fleurieu Peninsula . 81 Penola & the Coonawarra Wine Region . 119 South Australian McLaren Vale . 81 Wine & Food . 33 Willunga . 83 Your Outback Trip . 38 Gulf St Vincent Beaches . 84 WESTERN Travel with Children . 47 Victor Harbor . 86 SOUTH AUSTRALIA 120 Regions at a Glance . 49 Port Elliot . 87 Yorke Peninsula . 121 Goolwa . 88 West Coast . 121 Kangaroo Island . 89 East Coast . 122 MATT MUNRO/LONELY PLANET © PLANET MUNRO/LONELY MATT Penneshaw & South Coast & Dudley Peninsula . 92 Innes National Park . 122 American River . 93 Eyre Peninsula & the West Coast . 124 Kingscote . .. 94 Port Augusta . 124 North Coast Road . 95 Port Lincoln . 125 South Coast Road . 96 Coffin Bay . 127 Flinders Chase National Park . 97 Streaky Bay & Around . 127 Ceduna . 128 BAROSSA VALLEY & Ceduna to the Western SOUTHEASTERN Australia Border . 128 ALICE SPRINGS P196 SOUTH AUSTRALIA 99 Barossa Valley . 102 OUTBACK Tanunda . -

Demographics

Data Compendium Demographics Chief Public Health Officer’s Report 2016-2018 DEMOGRAPHICS Population Indicator: estimated resident population (ERP) Measure: Annual percentage change in estimated resident population in South Australia. Australian Bureau of Statistics estimated the resident population of South Australia to be 1,712,843 people in June 2016, representing about 7.1% of the total Australian population (24.2 million people).[2] Over three quarters of South Australia’s population reside in the greater Adelaide region. Between the years 2011 to 2016, the population in South Australia increased by 4.5% (73,229 people). The annual population growth rate from 2011 to 2016 for South Australia ranged from the lowest 0.60% in 2016 to the highest 0.93% in 2014. South Australia had the third slowest growth across all States and Territories in 2016 (ahead of Tasmania and Northern Territory).[3] Table 1: Estimated resident population, South Australia, 2006-2017 Year 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 Greater Adelaide 1189243 1204210 1219523 1237354 1253097 1264091 Rest of SA 363286 366409 369142 371548 374225 375523 South Australia 1552529 1570619 1588665 1608902 1627322 1639614 Year 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 Greater Adelaide 1277850 1289696 1302079 1313419 1324057 1334167 Rest of SA 378875 381792 384866 387249 388786 389504 South Australia 1656725 1671488 1686945 1700668 1712843 1723671 Population are at the end of June of each year, and 2017 population is subject to revision according to ABS. Source: 3101.0 Australian Demographic Statistics, -

South Australia's Climate Change Challenge and Opportunity

South Australia’s Climate Change Challenge and Opportunity Ross Garnaut September 2020 PB South Australia’s Climate Change Challenge and Opportunity Ross Garnaut September 2020 1 Summary of key points South Australia has a compelling interest in the success of the global effort to reduce damage from climate change. It can prosper exceptionally in success. Low renewable electricity Manufacturing and mining prices are the foundation for emissions are high and have not global competitiveness in fallen since 2009. These industries new manufacturing, including can move towards zero net the processing of South emissions over the next decade and Australian raw materials. during this time expand greatly. • South Australia has led a transition to • The largest miners and metal manufacturers a more reliable and secure low-carbon are committed to zero net emissions. power supply and now has lower wholesale There are advantages for trading zero- electricity prices than the most populous carbon metals within European markets states and is a net electricity exporter. now and other markets thereafter. • Renewable energy and storage investment • Green steel holds great opportunity in South can quickly lift employment and incomes in Australia from magnetite deposits, low South Australia’s post-pandemic recovery cost renewable energy for hydrogen, and as well as support electrification of transport bolstered by Whyalla human skills, education and expansion of energy-intensive industry. and training facilities. South Australia has the required physical infrastructure in place for • The biggest constraint on renewables expanding zero emission manufacturing. expansion is in planning and regulating the transmission and distribution network. Priority: Provide fiscal support for innovation to accelerate low-emission industrial inputs such as Priority: Facilitate investment in new energy hydrogen in heavy industry, iron-processing and transmission to enable increased energy other minerals processing. -

A Colonial History of the River Murray Dispute

Adam Webster* A COLONIAL HISTORY OF THE RIVER MURRAY DISPUTE ABSTRACT This article examines the history of the dispute over the sharing of the waters of the River Murray between the colonies, with particular emphasis on the period from the mid-1880s to the mid-1890s. The article shows that the change in water use by the colonies during this period had a signifi- cant impact on the question of how the water should be shared between the colonies. The article examines the early legal arguments regarding the ‘rights’ of the colonies to the waters of the River Murray and argues that these early legal analyses influenced the drafting of the Australian Consti- tution, which in turn has influenced the way similar disputes between the states are resolved today. I INTRODUCTION alk of reducing the flow of the waters of the River Murray evokes strong emotions in South Australians, and especially in their members of parliament.1 TThis is not a recent phenomenon and has been the case since colonial times.2 This article examines the history of the dispute over the sharing of the waters of the River Murray between the colonies, with particular emphasis on the period from the mid-1880s to the mid-1890s. I argue that this period, in the lead up to the Austra- lasian Federal Conventions of the 1890s, shaped the Convention debates, which in turn influenced the drafting of the Australian Constitution and the way in which the issue of the sharing of the waters of the River Murray between the states has been dealt with since Federation. -

Early European Interaction with Aboriginal Hunters and Gatherers on Kangaroo Island, South Australia

Early European interaction with Aboriginal hunters and gatherers on Kangaroo Island, South Australia Philip A. Clarke The earlier written history of European settlement in Australia generally portrays the Aboriginal inhabitants as being at best inconsequential or at worst a hindrance to the development of a Western nation. For instance, early this century, Blacket gave his impression of the role of Aboriginal people in the early years of European settlement in South Australia by saying These children of the bush...gave the early settlers much trouble.'639582*l1 Similar opinions of South Australian history were later provided by Price and Gibbs.“ However, elsewhere modern scholars, such as Baker and Reynolds, are putting forward views that Aboriginal people had important roles in the setting up of the British colonies across Australia.' They demonstrate that the contribution of Aboriginal people to the colonising process has been an underestimated aspect of Australian history. Following this argument, I am concerned here with assessing the importance of Aboriginal hunter/gatherer knowledge and technology to the early European settlement of South Australia. Kangaroo Island is where the first unofficial settlements were established by European sealers, who brought with them Aboriginal people from Tasmania, and obtained others from the adjacent coastal areas of South Australia. This is an important region for the study of the early phases of European interaction with Aboriginal people. Thus, this paper is primarily a discussion of how and what European settlers absorbed from Aboriginal people and their landscape. The period focussed upon is from the early nineteenth century to just after the foundation of the Colony of South Australia in 1836.