'Relocalization and Prefigurative Movements

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Art Schools Burning and Other Songs of Love and War: Anti-Capitalist

Art Schools Burning and Other Songs of Love and War: Anti-Capitalist Vectors and Rhizomes By Gene Ray Kurfürstenstr. 4A D-10785 Berlin Email: [email protected] Ku’e! out to the comrades on the occupied island of O’ahu. Table of Contents Acknowledgments iv Preface: Is Another Art World Possible? v Part I: The One into Two 1 1. Art Schools Burning and Other Songs of Love and War 2 2. Tactical Media and the End of the End of History 64 3. Avant-Gardes as Anti-Capitalist Vector 94 Part II: The Two into... X [“V,” “R,” “M,” “C,”...] 131 4. Flag Rage: Responding to John Sims’s Recoloration Proclamation 132 5. “Everything for Everyone, and For Free, Too!”: A Conversation with Berlin Umsonst 152 6. Something Like That 175 Notes 188 Acknowledgments As ever, these textual traces of a thinking in process only became possible through a process of thinking with others. Many warm thanks to the friends who at various times have read all or parts of the manuscript and have generously shared their responses and criticisms: Iain Boal, Rozalinda Borcila, Gaye Chan, Steven Corcoran, Theodore Harris, Brian Holmes, Henrik Lebuhn, Thomas Pepper, Csaba Polony, Gregory Sholette, Joni Spigler, Ursula Tax and Dan Wang. And thanks to Antje, Kalle and Peter for the guided glimpse into their part of the rhizomes. With this book as with the last one, my wife Gaby has been nothing less than the necessary condition of my own possibility; now as then, my gratitude for that gift is more than I can bring to words. -

Solidarity Economy: Key Concepts and Issues

Published in Kawano, Emily and Tom Masterson and Jonathan Teller-Ellsberg (eds). Solidarity Economy I: Building Alternatives for People and Planet. Amherst, MA: Center for Popular Economics. 2010. Solidarity Economy: Key Concepts and Issues Ethan Miller People across the United States and throughout the world are experiencing the devastating effects of an economy that places the profit of a few above the well being of everyone else. The political and business leaders who benefit from this arrangement consistently proclaim that there are no real alternatives, yet citizens and grassroots organizations around the world are boldly demonstrating otherwise. A compelling array of grassroots economic initiatives already exist, often hidden or marginalized, in the “nooks and crannies” of the dominant economy: worker, consumer and producer cooperatives; fair trade initiatives; intentional communities; alternative currencies; community-run social centers and resource libraries; community development credit unions; community gardens; open source free software initiatives; community supported agriculture (CSA) programs; community land trusts and more. While incredibly diverse, these initiatives share a broad set of values that stand in bold contrast to those of the dominant economy. Instead of enforcing a culture of cutthroat competition, they build cultures and communities of cooperation. Rather than isolating us from one another, they foster relationships of mutual support and solidarity. In place of centralized structures of control, they move us towards shared responsibility and directly democratic decision-making. Instead of imposing a single global monoculture, they strengthen the diversity of local cultures and environments. Instead of prioritizing profit over all else, they encourage commitment to broader work for social, economic, and environmental justice. -

The Social and Solidarity Economy: Towards an ‘Alternative’ Globalisation*

The Social and Solidarity Economy: Towards an ‘Alternative’ Globalisation* Background paper prepared by: NANCY NEAMTAN Présidente du Chantier de l’économie sociale In preparation for the symposium Citizenship and Globalization: Exploring Participation and Democracy in a Global Context Sponsored by: The Carold Institute for the Advancement of Citizenship in Social Change Langara College, Vancouver, June 14-16, 2002 *Translation: Anika Mendell The Carold Institute appreciates the financial assistance for translation provided by the Canadian Commission for UNESCO. The Social and Solidarity Economy: Towards an “Alternative” Globalisation Introduction The social and solidarity economy are concepts that have become increasingly recognised and used in Quebec since 1995. Following the examples of certain European, as well as Latin American countries, these terms emerged in Quebec as part of a growing will and desire on the part of social movements to propose an alternative model of development, in response to the dominant neo-liberal model. The emergence of this movement has not been without debate, nor obstacles. In fact, the contours and composition of the social economy are still being determined; its definition continues to evolve. However, after the second World Social Forum, which took place in Porto Alegre in February 2002, where the social and solidarity economy were important themes, it is now clear that this movement is firmly inscribed in an international movement for an alternative globalisation. Defining the social and solidarity economy Since the terms “social economy” or “economy of solidarity” are not yet widely used in Canada, outside of Quebec, it is important to establish certain defining elements. The social economy combines two terms that are often contradictory: • “economy” refers to the concrete production of goods or of services by business or enterprise that contributes to a net increase in collective wealth. -

Marxism and the Solidarity Economy: Toward a New Theory of Revolution

Class, Race and Corporate Power Volume 9 Issue 1 Article 2 2021 Marxism and the Solidarity Economy: Toward a New Theory of Revolution Chris Wright [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/classracecorporatepower Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Wright, Chris (2021) "Marxism and the Solidarity Economy: Toward a New Theory of Revolution," Class, Race and Corporate Power: Vol. 9 : Iss. 1 , Article 2. DOI: 10.25148/CRCP.9.1.009647 Available at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/classracecorporatepower/vol9/iss1/2 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts, Sciences & Education at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Class, Race and Corporate Power by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Marxism and the Solidarity Economy: Toward a New Theory of Revolution Abstract In the twenty-first century, it is time that Marxists updated the conception of socialist revolution they have inherited from Marx, Engels, and Lenin. Slogans about the “dictatorship of the proletariat” “smashing the capitalist state” and carrying out a social revolution from the commanding heights of a reconstituted state are completely obsolete. In this article I propose a reconceptualization that accomplishes several purposes: first, it explains the logical and empirical problems with Marx’s classical theory of revolution; second, it revises the classical theory to make it, for the first time, logically consistent with the premises of historical materialism; third, it provides a (Marxist) theoretical grounding for activism in the solidarity economy, and thus partially reconciles Marxism with anarchism; fourth, it accounts for the long-term failure of all attempts at socialist revolution so far. -

After the New Social Democracy Offers a Distinctive Contribution to Political Ideas

fitzpatrick cvr 8/8/03 11:10 AM Page 1 Social democracy has made a political comeback in recent years, After thenewsocialdemocracy especially under the influence of the Third Way. However, not everyone is convinced that this ‘new social democracy’ is the best means of reviving the Left’s social project. This book explains why and offers an alternative approach. Bringing together a range of social and political theories After the After the new new social democracy engages with some of the most important contemporary debates regarding the present direction and future of the Left. Drawing upon egalitarian, feminist and environmental social democracy ideas it proposes that the social democratic tradition can be renewed but only if the dominance of conservative ideas is challenged more effectively. It explores a number of issues with this aim in mind, including justice, the state, democracy, welfare reform, new technologies, future generations and the new genetics. Employing a lively and authoritative style After the new social democracy offers a distinctive contribution to political ideas. It will appeal to all of those interested in politics, philosophy, social policy and social studies. Social welfare for the Tony Fitzpatrick is a Senior Lecturer in the School of Sociology and Social twenty-first century Policy, University of Nottingham. FITZPATRICK TONY FITZPATRICK TZPPR 4/25/2005 4:45 PM Page i After the new social democracy TZPPR 4/25/2005 4:45 PM Page ii For my parents TZPPR 4/25/2005 4:45 PM Page iii After the new social democracy Social welfare for the twenty-first century TONY FITZPATRICK Manchester University Press Manchester and New York distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave TZPPR 4/25/2005 4:45 PM Page iv Copyright © Tony Fitzpatrick 2003 The right of Tony Fitzpatrick to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

Solidarity Economy: Key Concepts and Issues

Published in Kawano, Emily and Tom Masterson and Jonathan Teller-Ellsberg (eds). Solidarity Economy I: Building Alternatives for People and Planet. Amherst, MA: Center for Popular Economics. 2010. Solidarity Economy: Key Concepts and Issues Ethan Miller People across the United States and throughout the world are experiencing the devastating effects of an economy that places the profit of a few above the well being of everyone else. The political and business leaders who benefit from this arrangement consistently proclaim that there are no real alternatives, yet citizens and grassroots organizations around the world are boldly demonstrating otherwise. A compelling array of grassroots economic initiatives already exist, often hidden or marginalized, in the “nooks and crannies” of the dominant economy: worker, consumer and producer cooperatives; fair trade initiatives; intentional communities; alternative currencies; community-run social centers and resource libraries; community development credit unions; community gardens; open source free software initiatives; community supported agriculture (CSA) programs; community land trusts and more. While incredibly diverse, these initiatives share a broad set of values that stand in bold contrast to those of the dominant economy. Instead of enforcing a culture of cutthroat competition, they build cultures and communities of cooperation. Rather than isolating us from one another, they foster relationships of mutual support and solidarity. In place of centralized structures of control, they move us towards shared responsibility and directly democratic decision-making. Instead of imposing a single global monoculture, they strengthen the diversity of local cultures and environments. Instead of prioritizing profit over all else, they encourage commitment to broader work for social, economic, and environmental justice. -

The Role of the Social and Solidarity Economy in Reducing Social Exclusion BUDAPEST CONFERENCE REPORT

The Role of the Social and Solidarity Economy in Reducing Social Exclusion BUDAPEST CONFERENCE REPORT 1–2 JUNE 2017 Department of Trade, Investment and Innovation (TII) Vienna International Centre, P.O. Box 300, 1400 Vienna, Austria Email: [email protected] www.unido.org 1 © UNIDO 2017. All rights reserved. This document has been produced without formal United Nations editing. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) con- cerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries, or its economic system or degree of development. Designations such as “de- veloped”, “industrialized” or “developing” are intended for statistical convenience and do not necessarily express a judgement about the stage reached by a particular country or area in the development process. Mention of firm names or commercial products does not constitute an endorsement by UNIDO. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report was prepared by Olga Memedovic, Theresa Rueth and Brigitt Roveti, of the Business Environment, Cluster and Innovation Division (BCI) in the UNIDO Department of Trade, Investment and Innovation (TII) and edited by Georgina Wilde. The report has bene- fited from the contributions of keynote speakers and panellists during the Budapest Conference on the Role of the Social and Solidarity Economy in Reducing Social Exclusion, organized by UNIDO and the Ministry for National Economy of Hungary, held on 1–2 June 2017. The organization of the Conference benefitted from the support of H.E. -

Social and Solidarity Economy and the Crisis: Challenges from the Public Policy Perspective

EAST-WEST Journal of ECONOMICS AND BUSINESS Journal of Economics and Business Vol. XXI– 2018, Nos 1-2 SOCIAL AND SOLIDARITY ECONOMY AND THE CRISIS: CHALLENGES FROM THE PUBLIC POLICY PERSPECTIVE Sofia ADAM DEMOCRITUS UNIVERSITY OF THRACE ABSTRACT Social and Solidarity Economy is adopted in the public policy agenda from a variety of actors including the European Commission, the Greek government but also grass-roots movements in crisis-ridden Greece. This paper unfolds diverse and often competing conceptualizations of Social and Solidarity Economy through their manifestations in concrete public policy agendas with particular emphasis on the recent introduction of the new legal framework in Greece (Law 4430/2016). In this way, the paper links academic and policy discourses and demonstrates that academic battles are of importance for public policy formulations. Our particular emphasis is on the disabling limits or the enabling potential of public policies for SSE initiatives. Keywords: Social solidarity economy, Public policies, Crisis, Greece JEL Classification: B5, P0 Introduction Social and Solidarity Economy (SSE) is often cited in policy, academic and public discourse as the main driver for the necessary reconstruction of the Greek economy in order to move beyond the current impasse of the crisis. To what extent are these expectations well grounded? More importantly which are the 223 EAST-WEST Journal of ECONOMICS AND BUSINESS main elements of a public policy towards the SSE which could facilitate this process? This paper addresses these questions by unfolding relevant debates on SSE. First of all, we define SSE and delineate differences with other concepts in use such as non-profit sector and social enterprises. -

EMES Conferences Selected Papers Towards “Qualitative Growth

Welfare societies in transition Roskilde, 16-17 April 2018 ECSP-6EMES-03 Towards “Qualitative growth”- oriented Collective Action Frameworks: Articulating Commons and Solidarity Economy Ana Margarida Esteves Roskilde, April 2018 Funded by the Horizon 2020 Framework Programme of the European Union This article/publication is based upon work from COST Action EMPOWER-SE, supported by COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology). EMES Conferences selected papers 2018 3rd EMES-Polanyi Selected Conference Papers (2018) Towards “Qualitative growth”-oriented Collective Action Frameworks: Articulating Commons and Solidarity Economy Ana Margarida Esteves Instituto Universitário de Lisboa (ISCTE-IUL), Centro de Estudos Internacionais, Lisboa, Portugal 1. Introduction Under what form would a convergence between the Commons and Solidarity Economy movements promote “qualitative growth” (Capra and Henderson 2014) in a way that also ensures equity, justice and participatory democracy in access to resources? What aspects in the predominant organizational forms emerging from these movements need to be addressed in order to make such convergence possible? This paper is based on an inductive comparative analysis of three major types of commons- based peer production (CBPP): An ecovillage, an “integral cooperative” and a self-identified commercialization-based solidarity economy network. Benkler (2006) defines CBPP as a modular form of socioeconomic production in which large numbers of people work cooperatively over any type of commons. The case -

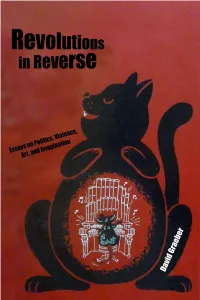

Revolutions in Reverse O

Minor Compositions Open Access Statement – Please Read This book is open access. This work is not simply an electronic book; it is the open access version of a work that exists in a number of forms, the traditional printed form being one of them. All Minor Compositions publications are placed for free, in their entirety, on the web. This is because the free and autonomous sharing of knowledges and experiences is important, especially at a time when the restructuring and increased centralization of book distribution makes it difficult (and expensive) to distribute radical texts effectively. The free posting of these texts does not mean that the necessary energy and labor to produce them is no longer there. One can think of buying physical copies not as the purchase of commodities, but as a form of support or solidarity for an approach to knowledge production and engaged research (particularly when purchasing directly from the publisher). The open access nature of this publication means that you can: • read and store this document free of charge • distribute it for personal use free of charge • print sections of the work for personal use • read or perform parts of the work in a context where no financial transactions take place However, it is against the purposes of Minor Compositions open access approach to: • gain financially from the work • sell the work or seek monies in relation to the distribution of the work • use the work in any commercial activity of any kind • profit a third party indirectly via use or distribution of the work • distribute in or through a commercial body (with the exception of academic usage within educational institutions) The intent of Minor Compositions as a project is that any surpluses generated from the use of collectively produced literature are intended to return to further the development and production of further publications and writing: that which comes from the commons will be used to keep cultivating those commons. -

Contribution of the Social and Solidarity Economy and of Social Finance to the Future of Work

PRINT-ENG-FINAL COVERi.pdf 1 12.03.20 15:32 THE CONTRIBUTION OF THE SOCIAL AND SOLIDARITY ECONOMY AND SOCIAL FINANCE TO THE FUTURE OF WORK Bénédicte Fonteneau and Ignace Pollet THE CONTRIBUTION OF SOCIAL AND SOLIDARITY ECONOMY FINANCE TO FUTURE WORK ISBN 978-92-2030855-4 ILO 9 789220 308554 The Contribution of the Social and Solidarity Economy and Social Finance to the Future of Work The Contribution of the Social and Solidarity Economy and Social Finance to the Future of Work Bénédicte Fonteneau and Ignace Pollet (Editors) with Youssef Alaoui Solaimani, Eric Bidet, Hyunsik Eum, Aminata Tooli Fall, Benjamin R. Quiñones and Mirta Vuotto Copyright © International Labour Organization 2019 Publications of the International Labour Office enjoy copyright under Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. Nevertheless, short excerpts from them may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated. For rights of reproduc- tion or translation, application should be made to ILO Publications (Rights and Licensing), International Labour Office, CH-1211 Geneva 22, Switzerland, or by email: [email protected]. The International Labour Office welcomes such applications. Libraries, institutions and other users registered with a reproduction rights organization may make copies in accordance with the licences issued to them for this purpose. Visit www.ifrro. org to find the reproduction rights organization in your country. The contribution of the social and solidarity economy and social finance to the future of work International Labour Office, Geneva, 2019 ISBN: 978-92-2-030855-4 (print) ISBN: 978-92-2-030856-1 (web pdf) Also available in French: La contribution de l'économie sociale et solidaire et de la finance solidaire à l’avenir du travail, ISBN: 978-92-2-030950-6 (print); ISBN: 978-92-2-030951-3 (web pdf), Geneva, 2019. -

Worker Cooperatives and the Solidarity Economy in Barcelona James Hooks [email protected]

Clark University Clark Digital Commons International Development, Community and Master’s Papers Environment (IDCE) 5-2018 Centering People in the Economy: Worker Cooperatives and the Solidarity Economy in Barcelona James Hooks [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.clarku.edu/idce_masters_papers Part of the International and Area Studies Commons, Political Economy Commons, Politics and Social Change Commons, and the Work, Economy and Organizations Commons Recommended Citation Hooks, James, "Centering People in the Economy: Worker Cooperatives and the Solidarity Economy in Barcelona" (2018). International Development, Community and Environment (IDCE). 189. https://commons.clarku.edu/idce_masters_papers/189 This Research Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Master’s Papers at Clark Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Development, Community and Environment (IDCE) by an authorized administrator of Clark Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Centering People in the Economy: Worker Cooperatives and the Solidarity Economy in Barcelona James A. Hooks March 2018 A MASTER’S RESEARCH PAPER Submitted to the faculty of Clark University, Worcester, Massachusetts, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in the department of International Development, Community, and Environment And accepted on the recommendation of Dr. Jude Fernando, Chief Instructor This project was partially funded through the IDCE Travel Award Approved by the Institutional Review Board of Clark University (IRB Protocol# 2016-095) Hooks 2 Acknowledgments I would like to begin this paper through acknowledging all those who have helped make this project a reality.