Summary of Information on Collecting, Growing and Planting Spinifex and Pingao

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trauma Affecting Asian-Pacific Islanders in the San Francisco Bay

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Trauma Affecting Asian-Pacific Islanders in the San Francisco Bay Area Pollie Bith-Melander 1, Nagia Chowdhury 2 ID , Charulata Jindal 3,* and Jimmy T. Efird 3,4 1 Chinatown Community Development Center, San Francisco, CA 94111, USA; [email protected] 2 Asian Community Mental Health Services, Oakland, CA 94607 USA; [email protected] 3 Centre for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics (CCEB), School of Medicine and Public Health, The University of Newcastle, Callaghan 2308, Australia; jimmy.efi[email protected] 4 Center for Health Disparities (CHD), Brody School of Medicine, East Carolina University, Greenville, NC 27834, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +61-481380244 Academic Editor: Paul B. Tchounwou Received: 23 June 2017; Accepted: 9 September 2017; Published: 12 September 2017 Abstract: Trauma is a transgenerational process that overwhelms the community and the ability of family members to cope with life stressors. An anthropologist trained in ethnographic methods observed three focus groups from a non-profit agency providing trauma and mental health services to Asian Americans living in the San Francisco Bay Area of United States. Supplemental information also was collected from staff interviews and notes. Many of the clients were immigrants, refugees, or adult children of these groups. This report consisted of authentic observations and rich qualitative information to characterize the impact of trauma on refugees and immigrants. Observations suggest that collective trauma, direct or indirect, can impede the success and survivability of a population, even after many generations. Keywords: Asian Americans; exploitation; immigrants; mental health; refugees; trauma 1. -

Exploring Spinifex Biomass for Renewable Materials Building Blocks

Exploring Spinifex Biomass for Renewable Materials Building Blocks Nasim Amiralian A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2014 Australian Institute for Bioengineering and Nanotechnology i Abstract Triodia pungens is one of the 69 species of an Australian native arid grass spinifex which covers approximately 27 % (2.1 million km2) of the Australian landmass. The use of fibrous and resinous components of spinifex has been well documented in traditional indigenous Australian culture for thousands of years. In this thesis the utility of both the cellulosic and resinous components of this abundant biomass for modern applications, and a potential economy for our Aboriginal collaborators, were explored. One part of this study was focused on the optimisation of a resin extraction process using solvent, and the subsequent evaluation, via a field trial, of the potential use and efficacy of the resin as a termiticide. Termiticidal performance was evaluated by re-dissolving the extracted resin in acetone and coating on pine timber blocks. The resin-coated and control blocks (uncoated timber) were then exposed to a colony of Mastotermes darwiniensis termites, which are the most primitive active and destructive species in subterranean areas, at a trial site in northeast Australia, for six months. The results clearly showed that spinifex resin effectively protected the timber from termite attack, while the uncoated control samples were extensively damaged. By demonstrating an enhanced termite resistance, it is shown that plant resins that are produced by arid/semi-arid grasses could be potentially used as treatments to prevent termite attack. -

24. Tribe PANICEAE 黍族 Shu Zu Chen Shouliang (陈守良); Sylvia M

POACEAE 499 hairs, midvein scabrous, apex obtuse, clearly demarcated from mm wide, glabrous, margins spiny-scabrous or loosely ciliate awn; awn 1–1.5 cm; lemma 0.5–1 mm. Anthers ca. 0.3 mm. near base; ligule ca. 0.5 mm. Inflorescence up to 20 cm; spike- Caryopsis terete, narrowly ellipsoid, 1–1.8 mm. lets usually densely arranged, ascending or horizontally spread- ing; rachis scabrous. Spikelets 1.5–2.5 mm (excluding awns); Stream banks, roadsides, other weedy places, on sandy soil. Guangdong, Hainan, Shandong, Taiwan, Yunnan [Bhutan, Cambodia, basal callus 0.1–0.2 mm, obtuse; glumes narrowly lanceolate, India, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Nepal, Philippines, Sri back scaberulous-hirtellous in rather indistinct close rows (most Lanka, Thailand, Vietnam; Africa (probably introduced), Australia obvious toward lemma base), midvein pectinate-ciliolate, apex (Queensland)]. abruptly acute, clearly demarcated from awn; awn 0.5–1.5 cm. Anthers ca. 0.3 mm. Caryopsis terete, narrowly ellipsoid, ca. 3. Perotis hordeiformis Nees in Hooker & Arnott, Bot. Beech- 1.5 mm. Fl. and fr. summer and autumn. 2n = 40. ey Voy. 248. 1838. Sandy places, along seashores. Guangdong, Hebei, Jiangsu, 麦穗茅根 mai sui mao gen Yunnan [India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Nepal, Myanmar, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Thailand]. Perotis chinensis Gandoger. This species is very close to Perotis indica and is sometimes in- Annual or short-lived perennial. Culms loosely tufted, cluded within it. No single character by itself is reliable for separating erect or decumbent at base, 25–40 cm tall. Leaf sheaths gla- the two, but the combination of characters given in the key will usually brous; leaf blades lanceolate to narrowly ovate, 2–4 cm, 4–7 suffice. -

Seagrasses and Sand Dunes

Seagrasses and Sand Dunes Coastal Ecosystems Series (Volume 3) Sriyanie Miththapala Ecosystems and Livelihoods Group Asia, IUCN iv Seagrasses and Sand Dunes Coastal Ecosystems Series (Volume 3) Sriyanie Miththapala Ecosystems and Livelihoods Group Asia, IUCN This document was produced by the fi nancial support of the German Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety (BMU) through a grant made to IUCN. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily refl ect those of IUCN or BMU. The designation of geographical entities in this report, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Published by: Ecosystems and Livelihoods Group Asia, IUCN Copyright: © 2008 IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorised without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Citation: Miththapala, S (2008). Seagrasses and Sand Dunes. Coastal Ecosystems Series (Vol 3) pp 1-36 + iii. Colombo, Sri Lanka: Ecosystems and Livelihoods Group Asia, IUCN. ISBN: 978-955-8177-73-0 Cover Photos: Top: Seagrasses in Agatti, Union Territory of Lakshadweep, India © Jerker Tamelander; Sand dunes in Panama, Southern Sri Lanka © Thushan Kapurusinghe, Turtle Conservation Project. Design: Sriyanie Miththapala Produced by: Ecosystems and Livelihoods Group Asia, IUCN Printed by: Karunaratne & Sons (Pvt) Ltd. -

Cenchrus Sandburs

... CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF cdfa FOOD & AGRICULTURE ~ California Pest Rating Proposal for Cenchrus echinatus L. (southern sandbur), C. spinifex Cav. (coast sandbur; field sandbur), C. longispinus (Hack.) Fernald (mat sandbur; longspine sandbur) Poales; Poaceae tribe Paniceae Current Rating: C Proposed Rating: C. echinatus – B; C. spinifex – B; C. longispinus – B Synonym for C. spinifex: C. incertus M. A. Curtis Comment Period: 10/09/2020 through 11/23/2020 Initiating Event: Three sandbur species in the genus Cenchrus have been designated as noxious weeds as defined by the California Food and Agriculture Code Section 5004 and are listed in Title 3, California Code of Regulations, Section 4500. A pest rating proposal is required to evaluate the current rating and status of these species in the state of California. History & Status: Background: Sandburs are panicoid grasses in the genus Cenchrus L. that are often designated as noxious weeds due to their prominent spiny fruiting burs. They usually grow in open or disturbed habitats and generally prefer sandy soils (Stieber and Wipff, 2003). In California, they usually are summer annuals to 0.6 m tall, and can grow to 1 m tall under favorable conditions (DiTomaso and Healy, 2007; Smith, 2012). Coast sandbur behaves as an annual in California, but can be biennial or a short- lived perennial elsewhere under different climate regimes (DiTomaso and Healy, 2007). The sandburs are characterized by an inflorescence of dense spikelike panicles of spiny burs. Each bur containing a group of 2 to 4 one-seeded spikelets surrounded by an involucre of flattened and spiny bristles. The plants can provide good forage for livestock before the burs develop. -

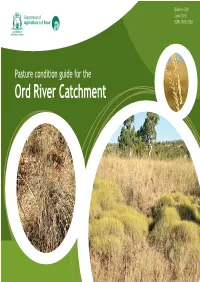

Pasture Condition Guide for the Ord River Catchment

Bulletin 4769 Department of June 2009 Agriculture and Food ISSN 1833-7236 Pasture condition guide for the Ord River Catchment Department of Agriculture and Food Pasture condition guide for the Ord River Catchment K. Ryan, E. Tierney & P. Novelly Copyright © Western Australian Agriculture Authority, 2009 Acknowledgements Photographs by S. Eyres and the Department of Agriculture and Food, Western Australia (DAFWA) Photographic Unit The information in this publication has been developed in consultation with experienced rangelands field staff providing services to the East Kimberley pastoral leases and with reference to Range Condition Guides for the West Kimberley Area, WA (Payne, Kubicki and Wilcox 1974) and Lands of the Ord–Victoria Area, WA and NT (Stewart et al. 1970). The authors would like to thank all those who provided valuable feedback on the design and content of this guide, including Andrew Craig, David Hadden and Matthew Fletcher (DAFWA Kununurra), Simon Eyres (DAFWA Photographic Unit), Alan Payne (retired DAFWA rangelands advisor), and members of the Halls Creek—East Kimberley Land Conservation District. This project was funded by Rangelands NRM WA using National Action Plan for Salinity and Water Quality funding. Rangelands NRM WA regards this project as a strategic investment which will contribute to an improved understanding and awareness of pasture condition in the Ord Catchment, leading to improved land management in that area. Rangelands NRM WA contracted the Department of Agriculture and Food WA to undertake the project. Funding for the National Action Plan for Salinity and Water Quality was provided by the Australian and Western Australian Governments. Disclaimer The Chief Executive Officer of the Department of Agriculture and Food and the State of Western Australia accept no liability whatsoever by reason of negligence or otherwise arising from the use or release of this information or any part of it. -

Native Grasses Make New Products – a Review of Current and Past Uses and Assessment of Potential

Native grasses make new products – a review of current and past uses and assessment of potential JUNE 2015 RIRDC Publication No. 15/056 Native grasses make new products A review of current and past uses and assessment of potential by Ian Chivers, Richard Warrick, Janet Bornman and Chris Evans June 2015 RIRDC Publication No 15/056 RIRDC Project No PRJ-009569 © 2015 Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation. All rights reserved. ISBN 978-1-74254-802-9 ISSN 1440-6845 Native grasses make new products: a review of current and past uses and assessment of potential Publication No. 15/056 Project No. PRJ-009569 The information contained in this publication is intended for general use to assist public knowledge and discussion and to help improve the development of sustainable regions. You must not rely on any information contained in this publication without taking specialist advice relevant to your particular circumstances. While reasonable care has been taken in preparing this publication to ensure that information is true and correct, the Commonwealth of Australia gives no assurance as to the accuracy of any information in this publication. The Commonwealth of Australia, the Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation (RIRDC), the authors or contributors expressly disclaim, to the maximum extent permitted by law, all responsibility and liability to any person, arising directly or indirectly from any act or omission, or for any consequences of any such act or omission, made in reliance on the contents of this publication, whether or not caused by any negligence on the part of the Commonwealth of Australia, RIRDC, the authors or contributors. -

Guide to Threatened Species of Kakadu National Park Including Other Plants and Animals of Interest

Guide to Threatened species of Kakadu National Park including other plants and animals of interest By Anne O’Dea This guide is for Kakadu National Park staff and bininj (local Traditional Owners and other Indigenous people of Kakadu). The guide highlights listed threatened species and some of the other significant plants and animals of Kakadu National Park at the time of printing. There are many more species that contribute to the rich biodiversity of the park, but these represent many of the species that are least often seen, or are significant to bininj. Please report sightings of species that are not often seen to Kakadu National Park staff. Phone: (08) 8938 1100 Email: [email protected] Cover photo by Anne O’Dea © 2014 Anne O’Dea The use of all photos has been generously donated for use in this book. Please respect the photographers’ rights and contact them or Kakadu National Park if you would like to seek permission to use any of the photos. Contents Habitats of Kakadu KEY ���������������������������������������������������������5 Some threats to wildlife and plants in Kakadu KEY ��������������6 Threatened species KEY ��������������������������������������������������������8 Traditional owner concern KEY ���������������������������������������������9 Tips to pronounce Gundjeihmi names �������������������������������10 Tips to pronounce Kunwinjku names ���������������������������������11 Tips to pronounce Jawoyn names ��������������������������������������12 Kakadu seasons ������������������������������������������������������������������13 -

Growth Characteristics and Anti-Wind Erosion Ability of Three Tropical Foredune Pioneer Species for Sand Dune Stabilization

sustainability Article Growth Characteristics and Anti-Wind Erosion Ability of Three Tropical Foredune Pioneer Species for Sand Dune Stabilization Jung-Tai Lee 1,*, Lin-Zhi Yen 1, Ming-Yang Chu 1, Yu-Syuan Lin 1, Chih-Chia Chang 1, Ru-Sen Lin 2, Kung-Hsing Chao 3 and Ming-Jen Lee 1 1 Department of Forestry and Natural Resources, National Chiayi University, Chiayi 60004, Taiwan; [email protected] (L.-Z.Y.); [email protected] (M.-Y.C.); [email protected] (Y.-S.L.); [email protected] (C.-C.C.); [email protected] (M.-J.L.) 2 Hsinchu Forest District Management Office, Forestry Bureau, Hsinchu 30046, Taiwan; [email protected] 3 Chiayi Forest District Management Office, Forestry Bureau, Chiayi 60049, Taiwan; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 25 March 2020; Accepted: 17 April 2020; Published: 20 April 2020 Abstract: Rainstorms frequently cause runoff and then the runoff carries large amounts of sediments (sand, clay, and silt) from upstream and deposit them on different landforms (coast, plain, lowland, piedmont, etc.). Afterwards, monsoons and tropical cyclones often induce severe coastal erosion and dust storms in Taiwan. Ipomoea pes-caprae (a vine), Spinifex littoreus (a grass), and Vitex rotundifolia (a shrub) are indigenous foredune pioneer species. These species have the potential to restore coastal dune vegetation by controlling sand erosion and stabilizing sand dunes. However, their growth characteristics, root biomechanical traits, and anti-wind erosion abilities in sand dune environments have not been documented. In this study, the root growth characteristics of these species were examined by careful hand digging. -

Construction of an Environmentally Sustainable Development on a Modified Coastal Sand Mined and Landfill Site—Part 2

Sustainability 2010, 2, 717-741; doi:10.3390/su2030717 OPEN ACCESS sustainability ISSN 2071-1050 www.mdpi.com/journal/sustainability Article Construction of an Environmentally Sustainable Development on a Modified Coastal Sand Mined and Landfill Site—Part 2. Re-Establishing the Natural Ecosystems on the Reconstructed Beach Dunes AnneMarie Clements 1, *, Appollonia Simmonds 1, Pamela Hazelton 2, Catherine Inwood 3, Christy Woolcock 4, Anne-Laure Markovina 5 and Pamela O’Sullivan 6 1 Anne Clements and Associates Pty Ltd, P.O. Box 1623, North Sydney 2059, Australia 2 Faculty of Engineering and IT, University of Technology, Sydney, P.O. Box 123, Broadway, NSW 2007, Australia; E-Mail: [email protected] 3 17 Canton Parade, Noraville, NSW 2263, Australia; E-Mail: [email protected] 4 Tentacle Inc., 2 Henderson Street, Norah Head, NSW 2263, Australia; E-Mail: [email protected] 5 School of Biological Sciences, University of Sydney, Building A10, Science Road, NSW 2006, Australia; E-Mail: [email protected] 6 Australasian Mycological Society, P.O. Box 154, Ourimbah, NSW 2258, Australia; E-Mail: [email protected] * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +61-2-9955-9733; Fax: +61-2-9957-4343. Received: 1 February 2010; in revised form: 25 February 2010 / Accepted: 1 March 2010 / Published: 9 March 2010 __________________________________________________________________________________ Abstract: Mimicking natural processes lead to progressive colonization and stabilization of the reconstructed beach dune ecosystem, as part of the ecologically sustainable development of Magenta Shores, on the central coast of New South Wales, Australia. -

Ecology, Habitat and Growth

Technical Article No. 7.1 - ecology, habitat and growth INTRODUCTION Spinifex (Spinifex sericeus R.Br.) is the major Spinifex often occurs with other indigenous sand indigenous sand dune grass that occurs on binding species on the foredune including pingao foredunes throughout most of the North Island (Ficinia spiralis), nihinihi (sand convolvulus, and the upper part of the South Island. Sometimes Calystegia soldanella), and hinarepe (sand referred to as silvery sand grass, or kowhangatara, tussock, Poa billardierei). it is the dominant sand binding plant on the seaward face of the foredune where its long trailing runners and vigorous growth make it an ideal sand dune stabiliser. In many North Island dunes, spinifex forms a near continuous colony for long stretches of sandy coastline. Technical Handbook Section 7: Native vegetation on foredunes Technical habitat and growth 7.1 Spinifex - ecoloogy, Article No. 7.1 - Spinifex - ecology, habitat and growth PLANT DESCRIPTION Spinifex is a stout perennial grass with strong on both surfaces (McDonald, 1983). At intervals of creeping runners or stolons. Leaves are usually 10-15 cm, new nodes are formed from which roots 5-10 mm wide and up to 38 cm long (Craig, 1984). emerge, take root and eventually a discrete plant The stolons can be up to 20 m long with internodes will form where there is sufficient space that is up to 38 cm long. Each node produces adventitious independent of the original stolon (Hesp, 1982). roots and upright, silvery green leaves that are hairy Vigorous spinifex on a foredune showing the upright silvery green leaves and long creeping runners or stolons that spread rapidly to occupy bare sand. -

Coastswap Coastal Management Case Studies (1/10)

CoastSWaP Coastal Management Case Studies (1/10) Improving coastal dune revegetation By Blair Darvill, January 2017 Background Successful revegetation within our southwest dune systems can be difficult due to the harsh coastal conditions of long, hot, dry summers, stormy winters, salt and sand laden winds. Damage also occurs by informal pedestrian or vehicle access. During CoastSWaP forums, coastal managers and community groups identified low (generally below 40%, however this can depend on expectations and scale) plant survival rates as a key issue. Combined with a drying climate and rising sea levels this only makes it harder to get a good coverage of native coastal plants to grow on the dunes. However, a few methods seem to be proving more successful than others, such as translocation and direct seeding of spinifex species, using a small number of hardy primary coloniser species, deep dune planting, and getting plants in the ground early in the wet season while it is still warm. Follow up watering is also being carried out where possible and is often the key component of success during an extended dry period. Stabilisation methods such as brushing go hand in hand with coastal revegetation, however this requires a case study of its own, so please also refer to the CoastSWaP article on Brushing in this series, http://coastswap.org.au/case-studies/ Revegetation with spinifex Spinifex Species Spinifex longifolius and Spinifex hirsutus are two species that are often the first (native) plant you will see up from the beach on the berm and seaward side of the primary dune. They have adapted to thrive in exposed sandy coastal areas (not suitable in rocky coastal sites as they grow in mobile sands) and are excellent primary colonisers and dune stabilisers.