Maryn Wilkinson, University of Amsterdam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abstract Resumen

http://www.interferenceslitteraires.be ISSN : 2031 - 2790 Katarzyna PASZKIEWICZ « She Looks Like a Little Piece of Cake » : Sofia Coppola and the Commerce of Auteurism Abstract Sofia Coppola, one of the most discussed female directors in recent years, is clearly embedded in the « commerce of auteurism » (Corrigan 1991), as she actively participates in constructing her authorial image. Building on existing scholarship on the filmmaker as illustra- tive of the new critical paradigm in the studies of women’s film authorship, this article will look at the critical discourses surrounding her films to trace the various processes of authentication and de-authentication of Coppola as an auteur. In my exploration of Coppola’s authorial status – how it is produced in the interaction of these multiple agencies – I will focus specifically on the case of Marie Antoinette (2006). The film, which arguably explores the nature of female cele- brity in the early 21st century, was criticized because of its disregard for historical accuracy, its fascination with surfaces and materiality, and because it offers a highly stylized objectification of the female protagonist. In reference to these critical responses, I will delineate the manifold ways in which Coppola’s authorship is expressed within the realm of material objects and spectacle. This analysis is enriched through a comparison to Sally Potter’s Orlando (1992), which can also be understood as a self-conscious declaration of authorial agency in relation to image making. The web of the possible intertextual relations between both films and Virginia Woolf’s source novel, Orlando: A Biography (1928), points more broadly to the complex network of possibilities and constraints for female authorship, as well as suggesting a critical shift towards a postfeminist moment, informed by changing discourses on consumption and feminine agency. -

Magisterarbeit

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OTHES MAGISTERARBEIT Titel der Magisterarbeit „Es war einmal MTV. Vom Musiksender zum Lifestylesender. Eine Programmanalyse von MTV Germany im Jahr 2009.“ Verfasserin Sandra Kuni, Bakk. phil. angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag. phil.) Wien, Februar 2010 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 066 841 Studienichtung lt. Studienblatt: Publizistik und Kommunikationswissenschaft Betreuerin / Betreuer: Ao. Univ. Prof. Dr. Friedrich Hausjell DANKSAGUNG Die Fertigstellung der Magisterarbeit bedeutet das Ende eines Lebensabschnitts und wäre ohne die Hilfe einiger Personen nicht so leicht möglich gewesen. Zu Beginn möchte ich Prof. Dr. Fritz Hausjell für seine kompetente Betreuung und die interessanten und vielseitigen Gespräche über mein Thema danken. Großer Dank gilt Dr. Axel Schmidt, der sich die Zeit genommen hat, meine Fragen zu bearbeiten und ein informatives Experteninterview per Telefon zu führen. Besonders möchte ich auch meinem Freund Lukas danken, der mir bei allen formalen und computertechnischen Problemen geholfen hat, die ich alleine nicht geschafft hätte. Meine Tante Birgit stand mir immer mit Rat und Tat zur Seite, ihr möchte ich für das Korrekturlesen meiner Arbeit und ihre Verbesserungsvorschläge danken. Zum Schluss danke ich noch meinen Eltern und all meinen guten Freunden für ihr offenes Ohr und ihre Unterstützung. Danke Vicky, Kathi, Pia, Meli und Alex! EIDESSTATTLICHE ERKLÄRUNG Ich habe diese Magisterarbeit selbständig verfasst, alle meine Quellen und Hilfsmittel angegeben und keine unerlaubten Hilfen eingesetzt. Diese Arbeit wurde bisher in keiner Form als Prüfungsarbeit vorgelegt. Ort und Datum Sandra Kuni INHALTSVERZEICHNIS I. EINLEITUNG .....................................................................................................1 I.1. Auswahl der Thematik................................................................................................ 1 I.2. -

Tropical Paradise

The Vol. 1 Issue 7 M a vTropical e r Paradise i c k May 2, 2011 By Meghan Darnell The Kiowa County High School Junior-Senior Prom was held at the Greens- This Month’s burg Recreation gym on April 16th. The promenade began at six in the evening, followed directly by the dinner. The prom theme was Tropical Night and the Features juniors decorated with tiki men and palm trees. For dinner, the juniors chose to o serve pork loin, a mashed potato casserole, green beans, Hawaiian rolls and fruit bowls with a key lime pie dessert. Honor At the dance, attendants were subjectivly entertained by a swing dance by Mr. Banquet... and Mrs. Calkins along with a dance-off between senior Shannon Webster and pg. 6 another student’s date. It was a very upbeat dance with two-steps, line-dances and the right balance of fast and slow songs. After the dance, students were allowed 30 minutes to change, and then were n bussed to the Mullinville gymnasium for After-Prom. At the After-Prom party, students were provided with a vast variety of games to win either cash or tickets for four big prizes that would be drawn at the end of the night. The big prizes were an Apple I-pad, an automobile tune-up set, a camera, an X-Box 360, a tele- vision and Blu-ray player and an I-pod touch. There were also prizes for guessing State Music... games. These games consisted of guessing the amount of change or golf balls in pg. -

Sofia Coppola and the Significance of an Appealing Aesthetic

SOFIA COPPOLA AND THE SIGNIFICANCE OF AN APPEALING AESTHETIC by LEILA OZERAN A THESIS Presented to the Department of Cinema Studies and the Robert D. Clark Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts June 2016 An Abstract of the Thesis of Leila Ozeran for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in the Department of Cinema Studies to be taken June 2016 Title: Sofia Coppola and the Significance of an Appealing Aesthetic Approved: r--~ ~ Professor Priscilla Pena Ovalle This thesis grew out of an interest in the films of female directors, producers, and writers and the substantially lower opportunities for such filmmakers in Hollywood and Independent film. The particular look and atmosphere which Sofia Coppola is able to compose in her five films is a point of interest and a viable course of study. This project uses her fifth and latest film, Bling Ring (2013), to showcase Coppola's merits as a filmmaker at the intersection of box office and critical appeal. I first describe the current filmmaking landscape in terms of gender. Using studies by Dr. Martha Lauzen from San Diego State University and the Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media to illustrate the statistical lack of a female presence in creative film roles and also why it is important to have women represented in above-the-line positions. Then I used close readings of Bling Ring to analyze formal aspects of Sofia Coppola's filmmaking style namely her use of distinct color palettes, provocative soundtracks, car shots, and tableaus. Third and lastly I went on to describe the sociocultural aspects of Coppola's interpretation of the "Sling Ring." The way the film explores the relationships between characters, portrays parents as absent or misguided, and through film form shows the pervasiveness of celebrity culture, Sofia Coppola has given Bling Ring has a central ii message, substance, and meaning: glamorous contemporary celebrity culture can have dangerous consequences on unchecked youth. -

'Spider-Man' Universe: Kurtzman to Direct

lifestyle SUNDAY, DECEMBER 15, 2013 ‘Spider-Man’ Universe: Kurtzman to direct ‘Venom,’ Goddard to write ‘Sinister Six’ ony Pictures Entertainment, in association with fourth “Amazing Spider-Man” movie will hit theaters on that Marc, Avi and Matt have begun to explore in ‘The Marvel Entertainment, is expanding its blockbuster May 4, 2018. Amazing Spider-Man’ and ‘The Amazing Spider-Man 2.’ S“Spider-Man” franchise with new projects including Avi Arad and Matt Tolmach will produce the films, We believe that Marc, Alex, and Drew have the uniquely “Venom” and “The Sinister Six,” the studio announced which will continue to build on the cinematic foundation exciting visions for how to expand the Spider-Man uni- Thursday night via ElectroArrives.com. Alex Kurtzman, established in the first two “Amazing Spider-Man” verse in each of these upcoming films,” said Columbia Roberto Orci and Ed Solomon will write “Venom,” which movies. Hannah Minghella and Rachel O’Connor will Pictures president Doug Belgrad. Goddard recently Kurtzman will direct, while Drew Goddard will write “The oversee the development and production of the films for signed on to write and direct the pilot for Marvel’s Netflix Sinister Six” with an eye to direct the film, which focuses the studio. Kurtzman, Orci, Pinkner, Solomon and series “Daredevil,” while Solomon co-wrote the surprise on the villains in Peter Parker’s universe. Goddard join Arad, Tolmach and Webb as members of hit “Now You See Me.” The character Venom debuted in Sam Raimi’s “Spider- the franchise’s brain trust, which will maintain the brand Universe building is all the rage amongst studios Man 3,” where he was played by Topher Grace. -

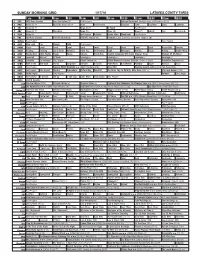

Sunday Morning Grid 1/17/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 1/17/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program College Basketball Michigan State at Wisconsin. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Paid Program Clangers Luna! LazyTown Luna! LazyTown 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Liberty Paid Eye on L.A. 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Seattle Seahawks at Carolina Panthers. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Man Land Paid Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local RescueBot Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Cook Moveable Martha Pépin Baking Simply Ming 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Raggs Space Edisons Travel-Kids Soulful Symphony With Darin Atwater: Song Motown 25 My Music 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Pumas vs Toluca República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Schuller In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Race to Witch Mountain ›› (2009, Aventura) (PG) Zona NBA Treasure Guards (2011) Anna Friel, Raoul Bova. -

April Steiner Wardrobe Stylist

APRIL STEINER WARDROBE STYLIST CELEBRITIES Abigail Breslin Christel Khalil Francesca Eastwood Adrianne Palicki Christina Hendricks Freddy Rodriguez Allison Sweeney Christine Lakin Gal Gadot Aly & AJ Cindy Crawford Giada DeLaurentiis America Ferrera Cole Hauser Gordon Ramsey Ana Ortiz Constance Marie Hilary Duff Andrea Bowen Danity Kane Hilary Winston Andrew Gunsberg Darren McMullen Holly Marie Combs Angela Lindvall Dax Shepard Hugh Laurie AnnaSophia Robb Diablo Cody Jack McBrayer Apolo Ohno Dominic Cooper Jackson Rathbone Arielle Kebbel Dominic Purcell James Denton Armie Hammer Doris Roberts James Maslow Ashlan Gorse Eddie McClintock James Woods Ashley Greene Eliza Dushku Jason Wahler Audrina Patridge Emilio Estevez Jennifer Stone Beau Garrett Emily VanCamp Jessalyn Gilsig Brittany Robertson Emma Bell Jill Larson Carrie Preston Eric Stonestreet Jim Parsons Cesar Milan Esai Morales Joel McHale Chandra Wilson Ever Carradine Joey McIntyre Charisma Carpenter Fiona Shaw Johnny Galecki Cheryl Burke Flava Flav Julia Ormond 1 Kaitlin Olson Michael Emerson Sarah Brown Karl Urban Michael Muhney Sasha Grey Kate Cazorla Michael Salahi Selita Ebanks Katie Holmes Michael Weatherly Seychelle Gabriel Keke Palmer Michelle Stafford Sharni Vinson Kelly Carlson Mindy Sterling Shawn Hatosy Kendra Wilkinson Miranda Cosgrove Sophia Bush Kerri Rhodes Morgan Eastwood Sterling Knight Kim Johnson Natalie Zea Steven Strait Kimberley Locke Nicole Richie Tamara Barney Kimberly Stewart Nicole Sullivan Tamara Jaber Kirstie Alley Nikki Cox Tamera Mowry Kristen Cavalleri -

Info Fair Resources

………………………………………………………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….…………… Info Fair Resources ………………………………………………………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….…………… SCHOOL OF VISUAL ARTS 209 East 23 Street, New York, NY 10010-3994 212.592.2100 sva.edu Table of Contents Admissions……………...……………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Transfer FAQ…………………………………………………….…………………………………………….. 2 Alumni Affairs and Development………………………….…………………………………………. 4 Notable Alumni………………………….……………………………………………………………………. 7 Career Development………………………….……………………………………………………………. 24 Disability Resources………………………….…………………………………………………………….. 26 Financial Aid…………………………………………………...………………………….…………………… 30 Financial Aid Resources for International Students……………...…………….…………… 32 International Students Office………………………….………………………………………………. 33 Registrar………………………….………………………………………………………………………………. 34 Residence Life………………………….……………………………………………………………………... 37 Student Accounts………………………….…………………………………………………………………. 41 Student Engagement and Leadership………………………….………………………………….. 43 Student Health and Counseling………………………….……………………………………………. 46 SVA Campus Store Coupon……………….……………….…………………………………………….. 48 Undergraduate Admissions 342 East 24th Street, 1st Floor, New York, NY 10010 Tel: 212.592.2100 Email: [email protected] Admissions What We Do SVA Admissions guides prospective students along their path to SVA. Reach out -

February 13Th, East Campus Get Food: 5:45Pm

Dormitory Council Meeting DormCon February 13th 2008, East Campus the dormitory council Minutes DormCon Agenda Wednesday, February 13th, East Campus Get food: 5:45pm Welcome 6pm Present: Baker, Burton Conner, EC, McCormick, New, Random, Senior House, Simmons Absent: Bexley, MacGregor, Next Updates 6.10pm: -Attendance and responsibilities reminder! -All Presidents should come to meetings or find a proxy! -Make sure you send out the agenda to your residents beforehand and the minutes afterwards -Housing -There was a meeting on Monday to look for people to be on the W1 Founders Group/Live there -Looking for people (about 10) who are interested in ?leading the charge? in figuring out the details of W1 -Another 40 people will be a part of an ?incubator? community that will move to NW35 for 2 years and they will then move to W1 -Applications are due next Wednesday February 20th -Email will be sent out to all undergrads soon -Green Hall will now house the Thetas and now all of Amherst Alley will be undergrad -i3 - discussion of issues with theme -?MIT Cribs? like MTV Cribs ? i3 chair wants at least a shot of the front door at the beginning and at the end of the i3 video -This stems from parents complaining that the i3 video does not show what the dorms actually look like -Dining - Blue Ribbon and CDAB -CDAB on Wednesday, February 20th at 5:30PM Location TBD -Send letters in support of having TechCash at Bertucci?s to Chris Hoffman <choffman> -The Subway right across the bridge now accepts TechCash and MIT is negotiating contract terms with Papa -

The Rise and Fall of Spring Break in Fort Lauderdale James Joseph Schiltz Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2013 Time to grow up: The rise and fall of spring break in Fort Lauderdale James Joseph Schiltz Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, History Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Recommended Citation Schiltz, James Joseph, "Time to grow up: The rise and fall of spring break in Fort Lauderdale" (2013). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 13328. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/13328 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Time to grow up: The rise and fall of spring break in Fort Lauderdale by James J. Schiltz A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major: History Program of Study Committee: Charles M. Dobbs, Major Professor James Andrews Edward Goedeken Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2013 Copyright © James J. Schiltz, 2013. All rights reserved. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES iv LIST OF FIGURES v INTRODUCTION: TROUBLE IN PARADISE 1 CHAPTER 1: “AT THE START THEY CAME TO FORT LAUDERDALE IN DRIBLETS, THEN BY SCORES, AND SOON BY HUNDREDS” 8 -

Healing Herb Fitness High Stress Less

CENTENNIAL SPOTLIGHT CENTENNIAL SPOTLIGHT ® ® WOMEN WEED™ STRESS& LESS HEALING HERB Discover the Marijuana's Calm of CBD Medical Miracles COVID-19 FITNESS HIGH Why the Plant How THC WOMEN & WEED & WOMEN Can Help Boosts Workouts ™ PLUS Is Cannabis CENTENNIAL SPECIALS the Female Viagra? Display Until 4/26/21 $12.99 CENTENNIAL SPOTLIGHT CENTENNIAL SPOTLIGHT ® ® WOMEN WEED™ STRESS& LESS HEALING HERB Discover the Marijuana's Calm of CBD Medical Miracles COVID-19 FITNESS HIGH Why the Plant How THC WOMEN & WEED & WOMEN Can Help Boosts Workouts ™ PLUS Is Cannabis CENTENNIAL SPECIALS the Female Viagra? Display Until 4/26/21 $15.99 CENTENNIAL SPOTLIGHT® WOMEN &WEED™ 2 WOMEN & WEED 3 SECTION 1 34 CANNABIS PRIMER 8 News of the Weed World 14 Words of Weed 54 EDITOR’S LETTER 16 Terpenes & Cannabinoids 20 Seven Studies to Know Now So 2020 was … well, it was 24 State of Disunion something. Between the 28 What’s Legal Where COVID-19 pandemic, murder You Live hornets, civil unrest and an election like no other, it’s no wonder so many of us are SECTION 2 excited to dive headfirst into 2021. And things are looking HEALTH AND WELLNESS good…at least on the cannabis 34 The Wonder Weed front. In this issue, we’ll talk 40 CBD and Stress about how weed won big in the 44 Could CBD Be the November elections, with five Female Viagra? states passing measures to 46 Weed With Your Workout legalize medical or adult-use marijuana and more soon to 50 When Pot Isn’t 28 follow, plus what the Biden Working for You administration means for federal legalization. -

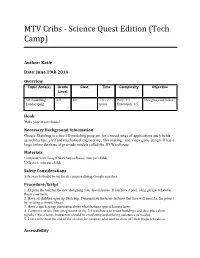

MTV Cribs - Science Quest Edition (Tech Camp)

MTV Cribs - Science Quest Edition (Tech Camp) Author: Katie Date: June 19th 2014 Overview Topic Area(s) Grade Cost Time Complexity Objective Level 3D modelling 4-5 $0 1.5 - 2 Prep: 1/3 Design a cool house Landscaping hours Execution: 3/5 Hook Make your dream house! Necessary Background Information Google Sketchup is a free 3D modeling program for a broad range of applications such fields as architecture, civil and mechanical engineering, film making, and video game design. It has a large online database of premade models called the 3D Warehouse. Materials Computer with Google Sketchup software (one per child) USB stick (one per child) Safety Considerations Safe search should be on for all campers during Google searches. Procedure/Script 1. Explain the task for the day: designing your dream house. It can have a pool, a big garage, whatever floats your boat. 2. Have all children open up Sketchup. Demonstrate the basic features that they will need for the project by creating a simple object. 3. Have a quick group discussion about what features typical houses have. 4. Campers can use their imagination or the 3D warehouse to create buildings and then place them together into a room. Instructors should be circulating and offering assistance as needed. 5. Leave time near the end of the session for campers who wish to show off their projects to do so. Accessibility . 1. Visual: Have a PDF walkthrough with pictures of different SketchUp tools and what they do. 2. Auditory: Explain the project verbally. 3. Kinesthetic: Campers learn what tools do by a trial and error method, mixed with Instructor aid and input.