Material Flow Analysis for the Island of Maui

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rethinking the Waste Hierachy

R ethinking the Waste H i erarchy Environmental ASSESSMENT INSTITUTE MARCH 2005 INSTITUT FOR MILJ0VURDERING E nvironmental Assessment Institute Reference no.: 2002-2204-007 ISBN.: 87-7992-032-2 Editors: Clemen Rasmussen and Dorte Vigs0 Written by: Clemen Rasmussen (project manager), Dorte Vigs0, Frank Ackerman, Richard Porter, David Pearce, Elbert Dijkgraaf and Herman Vollebergh. Published: March 2005 Version: 1.1 ©2005, Environmental Assessment Institute For further information please contact: Environmental Assessment Institute Linnesgade 18 DK -1361 Copenhagen Phone: +45 7226 5800 Fax: +45 7226 5839 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.imv.dk E nvironmental Assessment Institute Rethinking the Waste Hierarchy March 2005 Recommendations A number of specific recommendations for achieving cost-effective waste policies can be made based on both the US experience presented by Ackerman and Porter and on the analysis of European waste management presented by Pearce and Dijkgraaf & Vollebergh. The results of this project relate to both the target setting and the regulatory implementation of waste policy in the EU. The main recommendations for future waste policies in the EU and Member States are: ■ The waste hierarchy must be considered a very general and flexible guideline for formulating waste policies. What is environmentally desirable is not always a preferred solution, when considered from a socio economic perspective. The reason is that some environmental benefits may come at a comparably so cially high cost. The marginal costs and benefits will vary depending on mate rial and locality. It is recommended that social costs and benefits of new recy cling schemes should be analysed and that a critical assessment be made on to determine if further steps are in fact socially desirable. -

Solid Waste Master Plan Source Reduction Discussion II

John Fischer February 20, 2019 Master Plan Status & Schedule Update Spring, summer 2019: write draft plan Fall 2019: release public hearing draft Late 2020: publish final plan Upcoming Meetings March 14th C&D Subcommittee March 19th: Organics Subcommittee April 25th: Solid Waste Advisory Committee June 18th: C&D Suncommittee Source Reduction Strategies Identified at Jan. 17, 2019 Meeting Extended producer responsibility (EPR) PAYT and source reduction Right to repair The sharing economy Textile reuse Commercial waste reduction C&D source reduction Furniture refurbishment Resource management contracting Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) Enforce cardboard manufacturer responsibility to promote a closed loop system. Hold producers responsible if their packaging is not recyclable. Manufacturers should pay for people to send packaging back to them. Packaging responsibility should drive producers to think more about their packaging, which could drive source reduction. Support paint and electronics EPR bills filed this session. Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) Discussion question: What are the most important products or packaging for which we should establish EPR systems? PAYT and Source Reduction Promote PAYT within a framework of other initiatives that enable source reduction, e.g. a Library of Things. PAYT creates awareness, which can affect consumer behavior. PAYT and Source Reduction Discussion question: What steps should MassDEP take to increase/improve PAYT program adoption? Right to Repair Right to repair laws could help create new small repair businesses. Producers would be required to share all schematics of how a product works, which allows other businesses to repair the products, not just the original producers. Right to Repair Discussion question: What product categories provide the best repair business opportunities? The Sharing Economy Establish baseline of current reuse activities: identify the impact of systems such as Craigslist, Freecycle, Buy Nothing Facebook groups, and NextDoor.com. -

The Consumer's Handbook for Reducing Solid Waste

United States EPA 530-K-96-003 Environmental Protection September 1996 Agency Solid Waste and Emergency Response (5305W) The Consumer’s Handbook for Reducing Solid Waste Reduction Reuse Recycle Response This booklet describes how people can help solve a growing prob- lem...garbage! Individual consumers can help alleviate America’s mounting trash problem by making environmentally aware decisions about everyday things like shopping and caring for the lawn. Like the story that says cats have nine lives, so do many of the items we use every day. Empty cans and jars can be reused to store many items, such as nails or thumbtacks. The baking soda bought to bake a cake also can be used to scrub kitchen counters. The container that began its life as a plastic milk jug can be washed and reused to water plants, create an arts and crafts project, or be transformed into a bird feeder. Eventually, the milk jug can be recycled to create a new plastic product. Reusing products is just one way to cut down on what we throw away. This booklet outlines many practical steps to reduce the amount and toxicity of garbage. These aren’t the only steps that can be taken to reduce waste, but they’re a good start. L 1 Reduction Solid Waste Source Reduction A Basic Solution General Overview of What’s in America’s Trash Metals Yard Trimmings Source reduction is a basic solu- other management options that tion to the garbage glut: less waste deal with trash after it is already means less of a waste problem. -

RCRA, Superfund & EPCRA Call Center Training Module

United States Solid Waste and EPA530-K-02-019I Environmental Protection Emergency Response October 2001 Agency (5305W) RCRA, Superfund & EPCRA Call Center Training Module Introduction to: RCRA Solid Waste Programs Updated October 2001 DISCLAIMER This document was developed by Booz Allen Hamilton Inc. under contract 68-W-01-020 to EPA. It is intended to be used as a training tool for Call Center specialists and does not represent a statement of EPA policy. The information in this document is not by any means a complete representation of EPA s regulations or policies. This document is used only in the capacity of the Call Center training and is not used as a reference tool on Call Center calls. The Call Center revises and updates this document as regulatory program areas change. The information in this document may not necessarily reflect the current position of the Agency. This document is not intended and cannot be relied upon to create any rights, substantive or procedural, enforceable by any party in litigation with the United States. RCRA, Superfund & EPCRA Call Center Phone Numbers: National toll-free (outside of DC area) (800) 424-9346 Local number (within DC area) (703) 412-9810 National toll-free for the hearing impaired (TDD) (800) 553-7672 The Call Center is open from 9 am to 5 pm Eastern Time, Monday through Friday, except for federal holidays. RCRA SOLID WASTE PROGRAMS CONTENTS 1. Introduction............................................................................................................. 1 2. Municipal Solid Waste ......................................................................................... 2 2.1 EPA's Integrated Waste Management Hierarchy .................................... 3 2.2 Source Reduction ........................................................................................... 4 2.3 Recycling ........................................................................................................... 5 2.4 Combustion .................................................................................................... -

CHAPTER 4. FUTURE VISIONING the Purpose of This Chapter Is to Outline the Goals and Objectives of This RSWMP Document

CHAPTER 4. FUTURE VISIONING The purpose of this chapter is to outline the goals and objectives of this RSWMP document. Based on stakeholder input, analysis results, and a review of existing programs and practices related to regional solid waste management, a series of goals and subgoals was created to guide the TCOG Region over the next twenty years. These goals were periodically reviewed with the NRAC, TCOG staff and were further refined based on feedback received. A particular focus on waste minimization, cooperative commitment, public education, and outreach, and recommendations for a compost program were a primary focus during the development of these goals. Goals In total, there are four primary goals intended to guide the Region’s solid waste management practices over the next twenty years. Each primary goal is also supported by a series of corresponding subgoals, which outline more specific recommendations to incrementally achieve primary goals. Primary goals include the following: 1. Ensure adequate levels of transportation and disposal capabilities throughout the region. 2. Develop local programs in source reduction, waste minimization, reuse, recycling, and composting in order to conserve disposal capacity and resources. 3. Develop programs to assist regional and local entities in controlling and stemming illegal and improper disposal practices. 4. Develop cost-effective, efficient, and environmentally suitable solid waste management systems throughout the region. These four functional goals have served as the guiding principles for the Region since the original RSWMP was adopted in 1993. Upon review of stakeholder feedback and analysis results, these goals were deemed appropriate to continue functioning as guiding principles for the Region. -

Extended Producer Responsibility: the Next Phase of the US Recycling Movement

Extended Producer Responsibility: The Next Phase of the US Recycling Movement A Review of the Take It Back! Pacific Rim: Forging New Alliances for Waste Reduction Conference, held February 28 – March 1, 2000 in Los Angeles, California. The conference was produced by Raymond Communications, Inc. and Huls Environmental, L.L.C. and sponsored by The City of Los Angeles, California Integrated Waste Management Board, GTE Recycling, E-tech Products, Inc., and Waste Management of Orange County. By Neil N. Seldman Institute for Local Self-Reliance (ILSR) 2425 18th Street, NW Washington, DC 20009 (202)-232-4108 Neil Seldman is the director of the Institute for Local Self-Reliance’s (ILSR’s) Waste to Wealth Program. Under a grant from the Flora Foundation in San Francisco, California, ILSR will be exploring extended producer responsibility strategies and other rules that help close the loop locally. The U.S. recycling movement once again is flexing its muscles, this time in the direction of Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR). EPR proponents see discarded products and packages are an “unfunded mandate.” While some see unfunded mandates only as federal dictates that force spending at the local level, EPR advocates see unfunded mandates as corporate dictates that force local governments and small businesses to spend $43.5 billion annually for handling the materials that manufacturers so carelessly let loose upon the land. The EPR concept originated in Europe in the last decade, but now is emerging in Central and South America and Asia as well; paralleling the global path of the product and packaging manufacturers against whom the movement is aimed. -

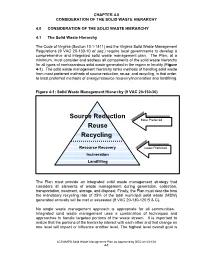

Consideration of the Solid Waste Hierarchy

CHAPTER 4.0 CONSIDERATION OF THE SOLID WASTE HIERARCHY 4.0 CONSIDERATION OF THE SOLID WASTE HIERARCHY 4.1 The Solid Waste Hierarchy The Code of Virginia (Section 10.1-1411) and the Virginia Solid Waste Management Regulations (9 VAC 20-130-10 et seq.) require local governments to develop a comprehensive and integrated solid waste management plan. The Plan, at a minimum, must consider and address all components of the solid waste hierarchy for all types of nonhazardous solid waste generated in the region or locality (Figure 4-1). The solid waste management hierarchy ranks methods of handling solid waste from most preferred methods of source reduction, reuse, and recycling, in that order, to least preferred methods of energy/resource recovery/incineration and landfilling. Figure 4-1: Solid Waste Management Hierarchy (9 VAC 20-130-30) Source Reduction Most Preferred Reuse Recycling Resource Recovery Least Preferred Incineration Landfilling The Plan must provide an integrated solid waste management strategy that considers all elements of waste management during generation, collection, transportation, treatment, storage, and disposal. Finally, the Plan must describe how the mandatory recycling rate of 25% of the total municipal solid waste (MSW) generated annually will be met or exceeded (9 VAC 20-130-120 B & C). No single waste management approach is appropriate for all communities. Integrated solid waste management uses a combination of techniques and approaches to handle targeted portions of the waste stream. It is important to realize that the portions of the hierarchy interact with each other and that change on one level will impact or influence another level. -

Briefing Paper: Oregon's Solid Waste Hierarchy

Briefing Paper: Oregon’s Solid Waste Hierarchy - Intent and Uses September 27, 2011 Primary Authors: David Allaway & Peter Spendelow "Reduce, Reuse, Recycle " has been part of the environmental lexicon since at least the first Earth Day in 1970, but Oregon was among the first states to adopt this as official policy in state law. The Recycling Opportunity Act of 1983 adopted a 5-step hierarchy for managing solid waste, with energy recovery and landfilling added below the other three. Passage of the 1991 Recycling Act added composting to the hierarchy below recycling and above energy recovery, so that the current law reads as follows: 459.015 Policy. (1).... (2) In the interest of the public health, safety and welfare and in order to conserve energy and natural resources, it is the policy of the State of Oregon to establish a comprehensive statewide program for solid waste management which will: (a) After consideration of technical and economic feasibility, establish priority in methods of managing solid waste in Oregon as follows: (A) First, to reduce the amount of solid waste generated; (B) Second, to reuse material for the purpose for which it was originally intended; (C) Third, to recycle material that cannot be reused; (D) Fourth, to compost material that cannot be reused or recycled; (E) Fifth, to recover energy from solid waste that cannot be reused, recycled or composted so long as the energy recovery facility preserves the quality of air, water and land resources; and (F) Sixth, to dispose of solid waste that cannot be reused, recycled, composted or from which energy cannot be recovered by landfilling or other method approved by the Department of Environmental Quality. -

(NPDES) Compliance Inspection Manual

NPDES Compliance Inspection Manual Chapter 17 EPA Publication Number: 305-K-17-001 Interim Revised Version, January 2017 U.S. EPA Interim Revised NPDES Inspection Manual | 2017 CHAPTER 17 – POLLUTION PREVENTION Contents A. Overview of Pollution Prevention ....................................................................................... 473 Pollution Prevention Goals .................................................................................................... 473 Waste Management Hierarchy ............................................................................................. 473 Pollution Prevention Benefits................................................................................................ 475 B. Pollution Prevention Opportunity Assessment Procedures for Industrial Facilities ............... 478 Preparation ............................................................................................................................ 479 Interview................................................................................................................................ 480 Facility Site Visit ..................................................................................................................... 480 C. Pollution Prevention Opportunity Assessment Procedures For Municipal wastewater treatment plants ............................................................................................................. 484 D. References ........................................................................................................................ -

Making Source Reduction and Reuse Work in Your

making source reduction and reuse work published by the Source Reduction Forum of the National Recycling Coalition, Inc. NATIONAL RECYCLING sou ‘h COALITIONINC tp/ co-sponsored by The Source Reduction Forum 01 the National Recycling Coalition A program of the National Recycling Coalition (NRC), the Source Reduction Forum’s goal is to conserve resources and reduce waste by: H encouraging the emcient use of materials, H developing and promoting source reduction and reuse strategies, and H integrating these strategies with recycling The Forum is coordinated by a steering committee composed of national source reduction experts from coin- mercial, government, university and non-profit sectors. Staffsupport is provided by the NRC. The ~ information in this report should not be considered policy positions of the National Recycling Coalition. Acknowledgments NRC would like to thank Local Government Workgroup Chair Naomi Friedman of the National Association of Counties, and Workgroup members Sally Boershig of Sunshares, Athena Lee Bradley of the Knox County,Tennessee Solid Waste Division, Joe Keyser of the Montgomery County, Maryland Department of Environmental Protection, Beth Graves of the North Carolina Division of Pollution Prevention and Environmental Assistance, Bruce Holland of the National Surplus Exchange Program, Hillary Johnson of Lane County, Oregon Waste Prevention and Recycling, Bill Lawrence of lMEX-I<ing County, Washington Dept. of Public Health, Pat McClearn of Colorado Hospitals for a Healthy Environment, Brenda Platt of the Institute for Local Self-Reliance, Sandi Sturm ofThe Energy Office, Hetty Versteege of the Boulder Energy Conservation Center, and Mark Wheeler of the Dutchess County New York Environmental Management Council for their assistance drafting this report. -

Chapter 3 - Solid Waste Management Hierarchy

Published This document was authored in 2004. For the latest information on the County’s Solid Waste Management Plan, please review the 2015 – 2035 update. Chapter Solid Waste Management Hierarchy 3 Consideration of the Solid Waste Management Hierarchy in the SWMP This chapter describes the solid waste management (SWM) hierarchy (defined in the Virginia Solid Waste Management Regulations) and discusses the consideration of the hierarchy in developing the SWMP. Consideration of the Solid Waste Management Hierarchy The Virginia Solid Waste Management Regulations, 9VAC20-130-140, requires that jurisdictions consider the SWM hierarchy defined in 9VAC20-130-30 in developing their SWMPs. The hierarchy establishes the preferred order of SWM alternatives as follows: source reduction, reuse, recycling, resource recovery, incineration, and landfilling (Figure 3-1). The Fairfax County fully integrated waste management plan considers and addresses all hierarchy components, plus transfer and collection services. Because no one method can manage all solid waste generated in the county, Fairfax County uses an integrated waste management system, where all components of the waste management hierarchy are necessary to deal with the amount of waste generated in the county. Fairfax County strives to create a Fairfax County strives to create a balanced SWM system, which uses all balanced SWM components of the waste management hierarchy, to meet the needs of system that meets the the community and comply with VDEQ requirements. needs of the community. 3-1 Chapter 3 - Solid Waste Management Hierarchy Figure 3-1. The Solid Waste Management Hierarchy Source Reduction Most Preferred Reuse Recycling Resource Recovery Waste Incineration Disposal Landfilling Least Preferred Source Reduction and Reuse Source reduction is the preferred method of waste management since it Source reduction and prevents the generation of waste in the first place. -

Plastic Source Reduction Working Group Meeting #3 Agenda

Plastic Source Reduction Working Group Meeting #3 Agenda May 21, 2020 8:30 AM to 1:00 PM Via Zoom Members of the public may attend the Zoom meeting by contacting Jaylen Ehara at [email protected] no later than 24 hours prior to the start of the meeting. Our objectives for this meeting are to (1) recap work completed; (2) review recommendations coming from Permitted Interaction Groups 1 and 2; (3) discuss Items 5 and 8 in the PIG-1 recommendations; and (4) establish Permitted Interaction Group #3. _________________________________________________________________________________________________ 8:30a Startup (Peter Adler) ● Welcome back ● Recap of preceding work ● Today’s agenda 8:45 Review of PIG-2 Recommendations (Attachment-A) ● Discussion / Additional Ideas? ● Fine Tuning 9:50 Break 10:00 Review of PIG-1 Recommendations (Attachment-B) ● Discussion / Additional Ideas? ● Discussion on #5 and #8 1 ● Fine Tuning 11: 30 Organize for PIG-3 and Tasks 5 & 6 2 (Attachment-C) 12:15p Next Steps ● Request for Legislative Extension on Act 254 (Dan Kouchi) ● Planning for the next meeting ● Review of the meeting plan (Attachment-D) 12:30 Public Comment (Until Finished) If you require an auxiliary aid or accommodation due to a disability, please contact (808) 586-4226 (voice/tty) or email Lane Otsu at [email protected] . For more information, contact DCAB at (808) 586-8121. 1 Items 5 and 8 do not come to the WG with consensus. Please review Zero Waste Hawaii’s proposed modifications for this discussion. 2 We will solicit self-nominations for PIG-3 and then try to create a balanced group.