DG38-15-1-3-T.Pdf (698.4Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Council Seeks to Keep Police out of Politics

Our second Today's weather: century NO" PROfiT ORG Partly sunny; of excellence US POSTAG! chance of PAID showers,. .high 75. ::c Ne"""cHk Qpl Prrm•l No 2& TGIF Student Center, University of De~ware, Newark, Delaware 19716 Vol. 113 No. 30-= Friday, May 15, 1987 Budget Council seeks will top \ to keep police \ $1 billion \ First time out of politics ever in Del. by James Colvard According to Mayor William Staff Reporter M. Redd Jr., the possibility of by Debbie Kalvlnsky a charter change was sparked Staff Reporter A report on a possible change in Newark's charter, by a change in the Police Bill Delaware's 1987-1988 budget to allow c;ity employees to ac of Rights which removed will be the state's first to top tively campaign for can restrictions on the political ac one billion dollars. didates in city elections added tivity of police officers. According to Bob Dowd, fuel to the ongoing dispute bet The Police Bill of Rights chief of fiscal and policy ween the mayor and police establishes a uniform set of analysis, the new budget will · force at Monday's City Coun rights to forces throughout the · be $1,004,723,500- a substan cil meeting. state, and allows police to par tial increase over the present In its report, the City ticipate in political cam operating budget of Charter Committee recom paigns, according to James $928,961,300. mended no change in the cur Weldin of the Newark Frater The rise is due to a $34 rent charter, which forbids nal Order of Police. -

Monthly Quiz List February 2021 Q Uiz # Q Uiz Type Fiction / N on Title

Monthly Quiz List February 2021 Reading Practice (RP) Quizzes Quiz # Quiz Type Fiction/ Non Title Author ISBN Publisher Level Interest Points Level Book Series Sweet Cherry 239741 RP F Alphablocks: ABC Publishing 978-1-78226-597-9 Sweet Cherry Publishing LY 0.5 1.7 Alphablocks 232827 RP F Dave Pigeon Swapna Haddow 978-0-571-32330-2 Faber and Faber LY 1 4.2 Dave Pigeon 239546 RP F Princess is Tired Jay Dale 978-1-4747-9960-7 Raintree LY 0.5 3 Engage Literacy Gold 239545 RP N Healthy Habits Kelly Gaffney 978-1-4747-9959-1 Raintree LY 0.5 3.2 Engage Literacy Gold 239547 RP N Reptiles Kelly Gaffney 978-1-4747-9957-7 Raintree LY 0.5 3.1 Engage Literacy Gold 239471 RP N Why People Move Kelly Gaffney 978-1-4747-9938-6 Raintree LY 0.5 3.8 Engage Literacy Lime 239474 RP F Nature Neighbours Jay Dale 978-1-4747-9952-2 Raintree LY 0.5 2 Engage Literacy Orange 239477 RP F Where's Farmer Belle? Jay Dale 978-1-4747-9943-0 Raintree LY 0.5 1.9 Engage Literacy Orange 239473 RP N Harvest Time Kelly Gaffney 978-1-4747-9946-1 Raintree LY 0.5 2.5 Engage Literacy Orange 239475 RP N Life in the Arctic Anne Giulieri 978-1-4747-9941-6 Raintree LY 0.5 2.9 Engage Literacy Purple 239476 RP N History of Flight Anne Giulieri 978-1-4747-9942-3 Raintree LY 0.5 3.2 Engage Literacy Purple 239023 RP F Gigantosaurus: Don't Cave In Cyber Group Studios 978-1-78741-314-6 Templar Publishing LY 0.5 3.4 Gigantosaurus 239024 RP F Gigantosaurus: The Lost Egg Cyber Group Studios 978-1-78741-313-9 Templar Publishing LY 0.5 3.2 Gigantosaurus 239731 RP N Rubbish Collectors Emily Raij -

WELLINGTON SHIRE LIBRARY NEW & Forthcoming BOOKS & Audio Visual

WELLINGTON SHIRE LIBRARY NEW & forthcoming BOOKS & Audio visual - april 2020 fiction Author Title Spine* Alderson, Sarah, In her eyes / AF Allcott, Charlene. More than a Mum / AF Andrews, V. C. Out of the attic / AF Baldwin, Jo, The good friend / AF Barrett, Julia, My sister is missing / AF Bell, Christine, No small shame / AF Belle, Kimberly, Dear wife / AF Bishop, Anne, The queen's bargain / AF Box, C. J., Long range / AF Brennan, Allison, The third to die / AF Briggs, David J. The claim / AF Broady, Sylvia, Daughter of the sea / AF Bryndza, Robert, Nine Elms / AF Butler, Sarah, Jack & Bet / AF Cavanagh, Steve, Fifty fifty / AF Chadwick, The Irish princess / AF Chambers, Queenie / AF Chater, Lauren, Gulliver's wife / AF Chavez, Heather, No bad deed / AF Cleave, Paul, Whatever it takes / AF Coates, Darcy, Voices in the snow / AF Cox, Helen (Helen Murder by the Minster / AF Cussler, Clive, Journey of the pharaohs / AF D'Alpuget, Blanche, The lioness wakes / AF Darke, Minnie, The lost love song / AF Diamond, Lucy, An almost perfect holiday / AF Dickinson, Miranda, The day we meet again / AF Docker, Sandie, The Banksia Bay Beach Shack / AF Dolan, Eva, Between two evils / AF Donohue, Rachel, The Temple House vanishing / AF Douglas, Donna, A mother's journey / AF Douglas-Home, The driftwood girls / AF Drinkwater, Carol, House on the edge of the cliff / AF Everett, Felicity, The move / AF Ewart, Andrew, Forget me / AF Fforde, Katie, A springtime affair / AF Fleet, Rebecca, The second wife / AF Foley, Lucy The guest list / AF French, Jackie, Lilies, lies and love / AF Gardner, Lisa, When you see me / AF Goldie, Luan, Nightingale Point / AF Goldsworthy, Anna, Melting moments / AF Goodman, Carol, The sea of lost girls : a novel / AF Goodwin, Rosie, Time to say goodbye / AF Gray, Alex. -

Alan Lomax: Selected Writings 1934-1997

ALAN LOMAX ALAN LOMAX SELECTED WRITINGS 1934–1997 Edited by Ronald D.Cohen With Introductory Essays by Gage Averill, Matthew Barton, Ronald D.Cohen, Ed Kahn, and Andrew L.Kaye ROUTLEDGE NEW YORK • LONDON Published in 2003 by Routledge 29 West 35th Street New York, NY 10001 www.routledge-ny.com Published in Great Britain by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane London EC4P 4EE www.routledge.co.uk Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group. This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.” All writings and photographs by Alan Lomax are copyright © 2003 by Alan Lomax estate. The material on “Sources and Permissions” on pp. 350–51 constitutes a continuation of this copyright page. All of the writings by Alan Lomax in this book are reprinted as they originally appeared, without emendation, except for small changes to regularize spelling. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lomax, Alan, 1915–2002 [Selections] Alan Lomax : selected writings, 1934–1997 /edited by Ronald D.Cohen; with introductory essays by Gage Averill, Matthew Barton, Ronald D.Cohen, Ed Kahn, and Andrew Kaye. -

Titles Ordered February 5 - 12, 2020

Titles ordered February 5 - 12, 2020 Blu-Ray Adventure Blu-Ray Release Date: Hanks, Tom News Of The World (BD/DVD Combo) http://catalog.waukeganpl.org/record=b1688843 3/23/2021 Jovovich, Milla Monster Hunter http://catalog.waukeganpl.org/record=b1688842 3/2/2021 Book Adult Non-Fiction Release Date: Blow, Charles M., 1970- author. The devil you know : a Black power manifesto / http://catalog.waukeganpl.org/record=b1688405 1/26/2021 Charles M. Blow. Lotz, Anne Graham, 1948- author. The light of His presence : prayers to draw you near http://catalog.waukeganpl.org/record=b1688845 10/6/2020 to the heart of God / Anne Graham Lotz. Children's Fiction Release Date: Albus, Kate, author. A place to hang the moon / Kate Albus. http://catalog.waukeganpl.org/record=b1688846 2/2/2021 Children's Graphic Novels Release Date: Abdo, Dan/ Patterson, Jason (ILT) Blue, Barry & Pancakes 1 http://catalog.waukeganpl.org/record=b1688993 3/9/2021 Ambrosio, Stefano, author. Wizards of Mickey. Origins volume one, Origins / http://catalog.waukeganpl.org/record=b1688976 11/17/2020 story by Stefano Ambrosio ; art by Lorenzo Pastrovicchio, Marco Gervaslo, Marco Palazzi, Alessandra Perina, Marco Mazzarello, Vitale Mangiatordi, Alessandro Pastrovicchio ; translation by Linda Ghio and Ste Aoki, Akira Star Wars Rebels 1 http://catalog.waukeganpl.org/record=b1688978 11/17/2020 Atkinson, Cale, author, artist. Simon and Chester : super detectives! / by Cale http://catalog.waukeganpl.org/record=b1688931 2/9/2021 Atkinson. Ayoub, Jenna, author, artist. Forever home / Jenna Ayoub. http://catalog.waukeganpl.org/record=b1688990 2/23/2021 Baltazar, Art Gillbert 3 : The Flaming Carats Evolution http://catalog.waukeganpl.org/record=b1688953 11/24/2020 Behling, Steve/ Usai, Luca (ILT)/ Florio, Silence and Science http://catalog.waukeganpl.org/record=b1688977 3/31/2021 Gianfranco (ILT)/ Cangialosi, Ciro (ILT) Benton, Jim, author, artist. -

In Mr. Knox's Country

In Mr. Knox's Country By Martin Ross IN MR. KNOX'S COUNTRY I THE AUSSOLAS MARTIN CAT Flurry Knox and I had driven some fourteen miles to a tryst with one David Courtney, of Fanaghy. But, at the appointed cross-roads, David Courtney was not. It was a gleaming morning in mid-May, when everything was young and tense and thin and fit to run for its life, like a Derby horse. Above us was such of the spacious bare country as we had not already climbed, with nothing on it taller than a thorn-bush from one end of it to the other. The hill-top blazed with yellow furze, and great silver balls of cloud looked over its edge. Nearly as white were the little white-washed houses that were tucked in and out of the grey rocks on the hill-side. "It's up there somewhere he lives," said Flurry, turning his cart across the road; "which'll you do, hold the horse or go look for him?" I said I would go to look for him. I mounted the hill by a wandering bohireen resembling nothing so much as a series of bony elbows; a white-washed cottage presently confronted me, clinging, like a sea-anemone, to a rock. I knocked at the closed door, I tapped at a window held up by a great, speckled foreign shell, but without success. Climbing another elbow, I repeated the process at two successive houses, but without avail. All was as deserted as Pompeii, and, as at Pompeii, the live rock in the road was worn smooth by feet and scarred with wheel tracks. -

Monday, 08. 04. 2013 SUBSCRIPTION

Monday, 08. 04. 2013 SUBSCRIPTION MONDAY, APRIL 7, 2013 JAMADA ALAWWAL 27, 1434 AH www.kuwaittimes.net Clashes after New fears in Burgan Bank Lorenzo funeral of Lanka amid CEO spells wins Qatar Egypt Coptic anti-Muslim out growth MotoGP Christians7 campaign14 strategy22 18 MPs want amendments to Max 33º Min 19º residency law for expats High Tide 10:57 & 23:08 Govt rebuffs Abu Ghaith relatives ‘Peninsula Lions’ may be freed Low Tide • 04:44 & 17:01 40 PAGES NO: 15772 150 FILS By B Izzak conspiracy theories KUWAIT: Five MPs yesterday proposed amendments to the residency law that call to allow foreign residents to Menopause!!! stay outside Kuwait as long as their residence permit is valid and also call to make it easier to grant certain cate- gories of expats with residencies. The five MPs - Nabeel Al-Fadhl, Abdulhameed Dashti, Hani Shams, Faisal Al- Kandari and Abdullah Al-Mayouf - also proposed in the amendments to make it mandatory for the immigration department to grant residence permits and renew them By Badrya Darwish in a number of cases, especially when the foreigners are relatives of Kuwaitis. These cases include foreigners married to Kuwaiti women and that their permits cannot be cancelled if the relationship is severed if they have children. These [email protected] also include foreign wives of Kuwaitis and their resi- dence permits cannot be cancelled if she has children from the Kuwaiti husband. Other beneficiaries of the uys, you are going to hear the most amazing amendments include foreign men or women whose story of 2013. -

Mariam Khachatryan.Pdf

AMERICAN UNIVERSITY OF ARMENIA College of Humanities and Social Sciences A Look at the AUA Pre-school English Program through the Lens of Montessori Pedagogy A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Teaching English as a Foreign Language By Mariam Khachatryan Irshat Madyarov, Adviser Liliana Edilyan, Reader Yerevan, Armenia 2014 We hereby approve that this thesis By Mariam Khachatryan Entitled A Look at the AUA Pre-school English Program through the Lens of Montessori Pedagogy Be accepted in partial fulfillment for the requirements of the degree Master of Arts in Teaching English as a Foreign Language Committee on the MA Thesis ………..………………………… Dr. Irshat Madyarov, Adviser ………..………………………… Liliana Edilyan, Reader ………..………………………… Dr. Irshat Madyarov MA TEFL Program Chair Yerevan, Armenia 2014 x xi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The completion of this thesis would not be possible without the support of several people. First of all, I want to express my greatest gratitude to the adviser of this thesis Dr. Irshat Madyarov for his valuable feedback, encouragement and patience throughout the course. I also thank the reader of the thesis Miss. Liliana Edilyan for her valuable comments and Dr. Raichle Farrelly for her encouragement. I like to express my thankfulness to the teachers of the AUA Pre-school English Program Ms. Melanie Nazarian and Ms. Arpy Shahverdian for their warm-hearted attitude and compassion towards my work. I want to appreciate my classmates’ help for their valuable ideas, especially Sona Budaghyan. I am also grateful to my friend Balu Vignesh for giving me his Video-camera to collect data and also for helping me out in the transcript analysis. -

470 Aim. the Purpose of This Study Is to Point out the Necessity Of

Aim. The purpose of this study is to point out the necessity of pharmaceutical and medical terminology. Materials and methods. The material of the study were pharmaceutical vocabulary units of different spheres of use. Research methods are description, comparison, analysis. Results and discussion. Pharmaceutical and medical English is the key to working and training abroad or in a multilingual environment. Knowing the exact terms of active ingredients, diseases, diagnoses, organs of the human body and examinations is an increasingly indispensable competence in an international environment such as medicine. Conclusion. It is a demanding but highly specialized activity, which no automatic translation program can do for you, and as a result is very well paid. If you work in the medical or pharmaceutical field, think about the opportunities you could have with a good English medical dictionary in this area: you can work and specialize abroad, write and talk to colleagues, doctors, staff and patients abroad, read texts and follow conferences in English. ORIGIN OF ENGLISH NAMES OF THE MONTHS Koval M. R. Scientific supervisor: Vnukova K.V. National University of Pharmacy, Kharkiv, Ukraine [email protected] Introduction. Actually, there are a lot of interesting facts in English history and culture about the origin of English names of the months. The calendar has gone through some changes. The ancient Roman calendar began in March and ended in February. And even though the calendar looked different than ours, the Romans did have a big impact on our calendar today. They came up with the names. Aim. To analyze and to investigate different ways of origin of English names of the months. -

Studies on Theenzymology of Purified Preparations of Brush Border

Biochem. J. (1973) 134, 43-57 43 Printed in Great Britain Studies on the Enzymology of Purified Preparations of Brush Border from Rabbit Kidney By S. G. GEORGE and A. J. KENNY Department of Biochemistry, University ofLeeds, 9 Hyde Terrace, Leeds LS2 9LS, U.K. (Received 16 November 1972) 1. A method for the preparation of brush border from rabbit kidneys is described. Contamination by other organelles was checked by electron microscopy and by the assay ofmarker enzymes and was low. 2. Seven enzymes, all hydrolases, were substantially enriched in the brush-border preparation and are considered to be primarily located in this structure. They are: alkaline phosphatase, maltase, trehalase, aminopeptidase A, aminopeptidase M, y-glutamyl transpeptidase and a neutral peptidase assayed by its ability to hydrolyse [1251]iodoinsulin B chain. 3. Adenosine triphosphatases were also present in the preparation, but showed lower enrichments. 4. Alkaline phosphatase was the most active phosphatase present in the preparation. The weak hydrolysis of AMP may well have been due to this enzyme rather than a specific 5'-nucleotidase. 5. The two disaccharidases in brush border were distinguished by the relative heat-stability of trehalase compared with that of maltase. 6. The individuality of the four peptidases was established by several means. The neutral peptidase and aminopeptidase M, both of which can attack insulin B chain, differed not only in response to inhibitors and activators but also in the inhibitory effect of a guinea-pig antiserum raised to rabbit aminopeptidase M. This antiserum inhibited both the purified and the brush-border activities of amino- peptidase M. -

Verses of the Last Cowboy in Sussex

VERSES OF ‘THE LAST COWBOY IN SUSSEX’ BY BILL LINDFIELD MT Editorial notes: Bill’s numbering has been followed in this edition. This means that there are gaps where no poem with that number was found amongst the copy set he passed to me. These may have been taken out by him for a poetry reading so may at a future date be found and included. Where a poem relates particularly to a chapter in The Last Cowboy, that chapter number is given. 1 2 The Dawn 3 The Five Senses 4 A Sorry Plight 5 Creations 6 The Old Carter's Thoughts 7 The Morning Ritual 8 My True Love 9 The Cuckoo 10 Morning Milking 11 The Cornfield 12 Haymaking Dreams 13 Have You Ever 14 Steepdown Hill 15 The Old Elm Trees 16 The Greatest Artist of All 17 The Old Rocking Chair 18 19 Suffering 20 The Turkey Farm 21 Those Stripling Years 22 The Learning Factory Chapter XXVII "The School" 23 Friendships Chapter XXXX "The Journeys of We Three" 24 How 25 The South Downs 26 Yew Tree Farm Chapter XXIII "West Street" 27 His Own Master 28 Dankton Lane Chapter XXV "Dankton Lane" 29 The Farming Year 30 Before You Can Look Around 31 A Nice September Day 32 The Long Hot Summers Day 33 Left Behind by Time 34 The Ploughing Match 35 36 Just a Game of Conkers 37 The Cavings Boy 38 The Annual Tadpole Day 39 Grandparents 40 Lambleys Chapter XXIX "Lambleys Lane" 41 My Lady Friends and I Chapter III "Over the Line" 42 43 Lychpool Farm 44 The Worker's Mark 45 Think of Tomorrow 46 Transition 47 Whatever Happened 48 The Passage of History 49 Who Knows 50 Symbol of Love 51 The Obvious Path 52 Progress -

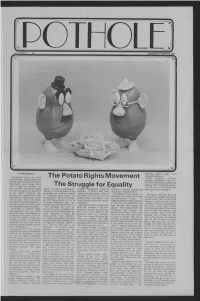

The Potato Rights Movement the Struggle for Equality

by DEE CEITFUL founding fathers didn’t even mention the potatoe.” Throughout history the world The Potato Rights Movement Idaho governor Clarence has seen many groups suffer from Spud peal commented, “ We owe a needless persecution and torment. lot to our little brown friends, the Fortunately, social change, albeit potatoes. Why without the potatoe, slow at times, has occurred and The Struggle for Equality we’d all have to eat brocoli and many of these persecuted groups against all local establishments symbolic ‘bag-burning,’ where the to protect America’s vital interest other squirmy green things. ” now have an equal role and plaee dealing in, what the leader of the members of F.E.V. will burn at all costs,” Schmidt stated. in our culture. However, per group, Hawkeye au Gratin, termed hundred of potatoe sacks. “ We feel According to Vinnie Shwaw, co According to Tatertot, the cruel secution and exploitation is still as “vegetable slave tradë.” Au like these activities will serve to ordinator of the American Potatoe treatment of potatoes and food in occurring for some groups with no Gratin stated, “ We’re damned fed- highten public awareness,” said Anti-defimation League, the general exists here on the UCSB end in sight. One of the worst up with being forced to live in Louie Tatertot of the Free Starch biggest problem facing the potatoe campus at the University Center examples of this mistreatment of a cramped cellophane bags and committee. in America is the predjudice that cafeteria. “ At first we thought that minority group is the daily abuse getting deep-fat fried all the time.” Although Tatertot was optimistic most humans feel towards the the UCen french fries weren’t that potatoes are forced to endure.