Is Japan a Middle Or an Abnormal Power?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Popular Culture Studies Journal

THE POPULAR CULTURE STUDIES JOURNAL VOLUME 6 NUMBER 1 2018 Editor NORMA JONES Liquid Flicks Media, Inc./IXMachine Managing Editor JULIA LARGENT McPherson College Assistant Editor GARRET L. CASTLEBERRY Mid-America Christian University Copy Editor Kevin Calcamp Queens University of Charlotte Reviews Editor MALYNNDA JOHNSON Indiana State University Assistant Reviews Editor JESSICA BENHAM University of Pittsburgh Please visit the PCSJ at: http://mpcaaca.org/the-popular-culture- studies-journal/ The Popular Culture Studies Journal is the official journal of the Midwest Popular and American Culture Association. Copyright © 2018 Midwest Popular and American Culture Association. All rights reserved. MPCA/ACA, 421 W. Huron St Unit 1304, Chicago, IL 60654 Cover credit: Cover Artwork: “Wrestling” by Brent Jones © 2018 Courtesy of https://openclipart.org EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD ANTHONY ADAH FALON DEIMLER Minnesota State University, Moorhead University of Wisconsin-Madison JESSICA AUSTIN HANNAH DODD Anglia Ruskin University The Ohio State University AARON BARLOW ASHLEY M. DONNELLY New York City College of Technology (CUNY) Ball State University Faculty Editor, Academe, the magazine of the AAUP JOSEF BENSON LEIGH H. EDWARDS University of Wisconsin Parkside Florida State University PAUL BOOTH VICTOR EVANS DePaul University Seattle University GARY BURNS JUSTIN GARCIA Northern Illinois University Millersville University KELLI S. BURNS ALEXANDRA GARNER University of South Florida Bowling Green State University ANNE M. CANAVAN MATTHEW HALE Salt Lake Community College Indiana University, Bloomington ERIN MAE CLARK NICOLE HAMMOND Saint Mary’s University of Minnesota University of California, Santa Cruz BRIAN COGAN ART HERBIG Molloy College Indiana University - Purdue University, Fort Wayne JARED JOHNSON ANDREW F. HERRMANN Thiel College East Tennessee State University JESSE KAVADLO MATTHEW NICOSIA Maryville University of St. -

Parent Vows to Fight 4-Day Week Plan Alcan Power Struggle Coming Here

Coping Getting a glimpse Sweep How victims services The art gallery welcomes Annual loggers programs here are the work of a New bonspiel draws .... dealing with cuts one Hazelton photographer 30 teams from B.! year later\NEWS A5 \COMMUNITY B3 and Alberta\SPORTS B4 .... t $1,00 PLUS 7¢ GST ($1.10 plus 8¢ GST outside of the Terrace area) ,r.= 0 0 0 It) ,tO O~ I IIIIg 75 b,. kNh~kR¥ 2003 TANDARD Parent vows to fight 4-day week plan By JENNIFER LANG ders the Grand Forks district, the first among parent and employee groups for The draft calendar proposes schools would be one 20-minute recess and a PARENTS HAVE not been adequately in B.C. to go to a four-day week, the one month prior to adoption. be in session from Monday to Thurs- 45 minute lunch for high schoolers. consulted on moving to a four-day plan was ditched, Purssell says. On April 16 the board meets with day, except when Mondays are statu- The district is also reviewing bus school week, says a local morn who "I really wish they would survey district parent advisory council repre- tory holidays. " schedules to see if routes can be ad- believes it's still not too late to fight us," Purssell said. "That way, the sentatives, the Terrace and District The district says it is responding to justed to lessen the impact of a longer the school board's money-saving plan. community can speak. It appears they Teachers' Union and CUPE staff to concerns in making the school day as day on kids who take the bus. -

The Top 365 Wrestlers of 2019 Is Aj Styles the Best

THE TOP 365 WRESTLERS IS AJ STYLES THE BEST OF 2019 WRESTLER OF THE DECADE? JANUARY 2020 + + INDY INVASION BIG LEAGUES REPORT ISSUE 13 / PRINTED: 12.99$ / DIGITAL: FREE TOO SWEET MAGAZINE ISSUE 13 Mohammad Faizan Founder & Editor in Chief _____________________________________ SENIOR WRITERS.............Nick Whitworth ..........................................Tom Yamamoto ......................................Santos Esquivel Jr SPECIAL CONTRIBUTOR....…Chuck Mambo CONTRIBUTING WRITERS........Matt Taylor ..............................................Antonio Suca ..................................................7_year_ish ARTIST………………………..…ANT_CLEMS_ART PHOTOGRAPHERS………………...…MGM FOTO .........................................Pw_photo2mass ......................................art1029njpwphoto ..................................................dasion_sun ............................................Dragon000stop ............................................@morgunshow ...............................................photosneffect ...........................................jeremybelinfante Content Pg.6……………….……...….TSM 100 Pg.28.………….DECADE AWARDS Pg.29.……………..INDY INVASION Pg.32…………..THE BIG LEAGUES THE THOUGHTS EXPRESSED IN THE MAGAZINE IS OF THE EDITOR, WRITERS, WRESTLERS & ADVERTISERS. THE MAGAZINE IS NOT RELATED TO IT. ANYTHING IN THIS MAGAZINE SHOULD NOT BE REPRODUCED OR COPIED. TSM / SEPT 2019 / 2 TOO SWEET MAGAZINE ISSUE 13 First of all I’ll like to praise the PWI for putting up a 500 list every year, I mean it’s a lot of work. Our team -

Volume 30 September 7, 2020 Number 17

Volume 30 Number 17 September 7, 2020 Volume 30 Number 17 Pages R000–R000; 000–000 September 7, 2020 R000–R000; 30 Number 17 Pages Volume ll CCURBIO_30_17.c1.inddURBIO_30_17.c1.indd 1 113-Aug-203-Aug-20 77:35:50:35:50 PPMM ll Magazine Correspondence generations) elicit violent fi ghts or ‘power consumption (Figure 1A). Stored acorns struggles’, among multiple same-sex are consumed by adults when food is Tracking the warriors coalitions from neighboring groups. Here, scarce and are also fed to nestlings. using an automated radio-telemetry Granaries are pilfered by intra- and and spectators of system, we found that individuals in interspecifi c competitors and are coalitions competing for breeding thus zealously defended by all group acorn woodpecker vacancies — the ‘warriors’ — invested members. Large-granary territories are wars up to ten hours per day on successive often controlled by polygynandrous days before one coalition emerged groups consisting of multiple male and victorious. Power struggles also attracted female breeders and their non-breeding 1,4, 1 Sahas Barve *, Ally S. Lahey , ‘spectators’— acorn woodpeckers not offspring (‘helpers’). Same-sex co- 2 Rebecca M. Brunner , eligible to fi ll the breeding vacancy. breeders are closely related to each other 3 1 Walter D. Koenig , and Eric L. Walters Apparently present only to gain social but unrelated to breeders of the opposite information, spectators travelled from sex [3]. In addition to within-group Although intergroup confl ict is territories as far as over three kilometers dynamics, acorn woodpeckers recognize widespread in vertebrates, simultaneous away. Our study reveals the complexity associations among individuals outside agonistic interactions among several of acorn woodpecker social group their group and track membership groups are rare [1]. -

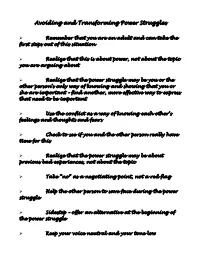

Avoiding and Transforming Power Struggles

Avoiding and Transforming Power Struggles Ø Remember that you are an adult and can take the first steps out of this situation Ø Realize that this is about power, not about the topic you are arguing about Ø Realize that the power struggle may be you or the other person’s only way of knowing and showing that you or she are important – find another, more effective way to express that need to be important Ø Use the conflict as a way of knowing each other’s feelings and thoughts and fears Ø Check to see if you and the other person really have time for this Ø Realize that the power struggle may be about previous bad experiences, not about the topic Ø Take “no” as a negotiating point, not a red flag Ø Help the other person to save face during the power struggle Ø Sidestep – offer an alternative at the beginning of the power struggle Ø Keep your voice neutral and your tone low Ø Avoid known trigger topics during the power struggle Ø You don’t always have to win – accept that and move on Ø Let others have the last word Ø Use conflict and negotiation skills – get training in these Ø Move away from the audience – don’t let your kids see you engaged in a power struggle Ø Sit down – make your body lower than the other person’s – it will diffuse the tension Ø Don’t get drawn into one if either of you is tired Ø Listen to the other person Ø Don’t moralize, sermonize, or use put downs Ø Listen to yourself, monitor your own behaviour Ø Ask the other person for ideas on how to resolve the problem Ø As soon as the other person moves the slightest bit toward compromise, you do the same Brenda McCreight Ph.D. -

Power Struggle and Diplomatic Crisis: Past, Present and Prospects of Sino‐Japanese Relations Over the Senkaku Conundrum

Power Struggle and Diplomatic Crisis: Past, Present and Prospects of Sino‐Japanese Relations over the Senkaku Conundrum East‐West Center in Washington February 13, 2013 Washington, DC Yasuhiro Matsuda Professor, The University of Tokyo Official Website: http://www.ioc.u‐tokyo.ac.jp/~ymatsuda/en/index.html Three Hypotheses A: Japan’s provocation B: China’s maritime expansionism C: Domestic politics in both China and Japan Matsuda’s view: C>B>A Hypothesis A: Japan’s provocation “Revival of militarism” “Right wing” dominates Japan “Challenge against post‐WWII order” Ishihara‐Noda axis’s conspiracy China can justify its every action by this, but China highly appreciated Japan’s peaceful development in 2008… Hypothesis B: China’s maritime expansionism South China Sea East China Sea West Pacific Establishment of the Leading Small Group of Maintenance of Maritime Interests (headed by Xi Jinping), “Sansha City” China has passed the “point‐of‐no‐return.” Without Japan’s concession, there will be no improvement of relations. Hypothesis C: Domestic politics China: leadership change and power struggle, ultra‐nationalism, criticism on the internet Japan: weak government, elections, bureaucratic red tape Political instability in both nations caused the problem. “2012 problem” is over. If both countries need cooperation for the sake of their own economy, they will seek improvement. Matsuda’s assumption Trigger: Japan’s action (Ishihara, Noda) Fundamental cause: domestic politics (power struggle in China) Background cause: China’s maritime expansion There will be a chance of improvement. Comparison: difference between China, Russia and Korea Northern Territory: Part of Hokkaido, the Soviets invaded in violation of the treaty and Japanese citizens were expelled. -

Between Families Foster Parent Retreats Avoiding Power Struggles in Foster Care Power Struggles Do Not Discriminate

IN THIS ISSUE: Foster Family Matters Recruitment Moment Care Provider of the Month Foster Parent Anniversaries July 2014 Foster Family Living Between Families Foster Parent Retreats Avoiding Power Struggles in Foster Care Power struggles do not discriminate. No matter what type anxiety, neglect and apprehension which foster of parent you are – single, married, adoptive or foster, no children experience. It is vital to a foster child’s success one is immune. All parents, at one time or another, have and healthy development for a foster parent to address been sucked into a tug-of-war struggle; both sides wanting these feelings and be a consistent, loving support as the to “win” the war. Power struggles for foster parents can be child works through the residual effects of a chaotic past. especially difficult since a foster child can often state, “I Most power struggles happen after a stressful event when don’t have to listen to you; you’re not my real mom (or the child becomes focused on what he wants and proving that dad).” Foster children often struggle with trust issues and he is right. In turn, parents can become focused on winning need to feel have to control whatever they can. Gaining the argument. When you realize that you are in a power control over situations is done in an effort to not feel struggle, recognize it and take steps to get out of it. Here are completely powerless. some suggestions to avoid or get out of a power struggle: On any given day in the United States, there are more than • Remove yourself from the situation; don’t allow yourself 500,000 children in foster care. -

The Way Church Should Be

FINDING SENSE IN SUFFERING Power Struggle Series - Part 7 Dan Burrell Good morning Life Fellowship. It is great to see you and it is great to know that there are many folks that are watching on the Internet this morning as we get back to our new version of normal step by step with Kid Life starting today and then also double services. And today we are going to be continuing our series on ‘Power Struggle. First, I want you to understand that my heart breaks when I am in those moments that I am just praying through our church. Those are the times that I specifically say I am going to disconnect; I am going to turn my phone off and leave it in the other room. On purpose I just want to disengage and I just want to think about the people in our church. And I will tell you that often as I do that, several emotions sweep across me. Sometimes it is deep pain, other times it is an overwhelming sense of gratitude. To be frank sometimes it is a sense of just simply being flat out overwhelmed. And it is because when you have as many people who call a church their home as this church has we always have people going through tons of different things and different challenges. I think about the ladies in this church who right now are dealing with the shock of having a husband say, ‘I don’t want to be married to you anymore.’ I think about the young couple who recently was excited about the birth of their first child only to find out a few weeks later that they have miscarried. -

Sermon Transcript

SPIRITUAL STRONGHOLDS Power Struggle Series - Part 4 Ben Rudolph Good morning Life Fellowship. It is good to see you here this morning. Turn in your Bibles to II Corinthians Chapter 10 where we are going to be this morning. I hope that you have been enjoying this series. For the last two weeks Pastor Dan has just done an amazing job. He talked about the power over sin two weeks ago and then last week the power over schemes as we have been looking in this series on spiritual warfare. We need to realize that as we live our lives we don’t just live in the material world, we don’t just live our lives freely walking with God, but we need to understand that there is an enemy that attacks us every moment of every day. One of the reasons why we were doing this series is so that we will be aware of how the enemy works. But even more so is the reason that we can have faith in what God is doing in spite of the enemy’s attacks. Part of this series is not so that we look upon the darkness of spiritual forces, and that we get scared and we retreat; the point of this is to understand what the enemy wants to do, how he is working and how he is active, and then understand how God is working in greater ways over the enemy of darkness. Amen? (Amen.) So that is why we are studying this. One of the fears of studying spiritual warfare is that we can get so caught up in looking at what the enemy is doing we fail to look at what God is doing. -

Power Struggle Between the European Parliament and the Council on the Eu Budget: Winners Or Losers?

THINKING EUROPE • PENSER L’EUROPE • EUROPA DENKEN BLOG POST POWER STRUGGLE BETWEEN THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND THE COUNCIL ON THE EU BUDGET: WINNERS OR LOSERS? 17/11/2020 | CHRISTINE VERGER | LAW AND INSTITUTIONS By Christine Verger, Vice-President of the Jacques Delors Institute, rapporteur of the Jacques Delors Institute’s Political Observatory of the European Parliament On 16 November, Hungary and Poland vetoed the European budget and the recovery plan with a view to causing the failure of the compromise between the European Parliament and the EU Council which con- ditions the disbursement of European funding to Member States on their compliance with the rule of law. What follows is an explanation of this compromise which is both institutionally and politically important. The historic agreement of 21 July During the European Council meeting held on 21 July 2020, the 27 Heads of State and of Government reached a historic agreement after four days and nights of arduous discussions on the EU budget for the 2021-2027 period (€1074 billion) and on the European recovery package (€750 billion, of which €390 bil- lion in grants, the rest in the form of loans). A pooling of States’ debt by the Commission to make transfers to Member States and to be reimbursed collectively was decided: a major first!1 The allocation of funding was made conditional on Member States’ compliance with the rule of law. However, the drawback and the result of a compromise requiring unanimity from all States was that much funding was reduced from the Commission’s initial proposal, particularly regarding research, education, digital technology, health and defence policies. -

Power Struggle Customers, Companies, and the Internet of Things by BRENNA SNIDERMAN and MICHAEL E

ISSUE 17 | 2015 Complimentary article reprint Power struggle Customers, companies, and the Internet of Things BY BRENNA SNIDERMAN AND MICHAEL E. RAYNOR > ILLUSTRATION BY ALEX NABAUM About Deloitte Deloitte refers to one or more of Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited, a UK private company limited by guarantee (“DTTL”), its network of member firms, and their related entities. DTTL and each of its member firms are legally separate and independent entities. DTTL (also referred to as “Deloitte Global”) does not provide services to clients. Please see www. deloitte.com/about for a more detailed description of DTTL and its member firms. Deloitte provides audit, tax, consulting, and financial advisory services to public and private clients spanning multiple industries. With a globally connected network of member firms in more than 150 countries and territories, Deloitte brings world-class capabilities and high-quality service to clients, delivering the insights they need to address their most complex business challenges. Deloitte’s more than 200,000 professionals are committed to becoming the standard of excellence. This communication contains general information only, and none of Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited, its member firms, or their related entities (collectively, the “Deloitte Network”) is, by means of this communication, rendering professional advice or services. No entity in the Deloitte network shall be responsible for any loss whatsoever sustained by any person who relies on this communication. © 2015. For information, contact Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited. 84 Deloitte Review | DELOITTEREVIEW.COM POWER STRUGGLE 85 Power struggle Customers, companies, and the Internet of Things BY BRENNA SNIDERMAN AND MICHAEL E. RAYNOR > ILLUSTRATION BY ALEX NABAUM s the Internet of Things (IoT) permeates people’s daily lives, potentially useful information can now be created every time someone adjusts a thermostat or turns an ignition key or pedals a home-gym exercise bike. -

The Power Struggle Between China, India and Japan Over Next Decade

Asian Critical Issues Series The Power Struggle Between China, India and Japan Over Next Decade Bill Emmott Former Editor in Chief, The Economist Thursday, June 19, 2008 4:00 - 5:30 pm Japan Information and Culture Center 1151 21st Street, NW The rising economic and political power of Asia is the biggest story of our times. But it is often misunderstood, either as a story of West vs. East or as a story simply of the rise of China and its challenge to America. In his new book "Rivals: How the Power Struggle Between China, India and Japan will Shape our Next Decade", Bill Emmott aims to challenge those views. The biggest story, Washington he argues, is and will be the rivalry within Asia now that, for the first time in history, the continent contains three great powers simultaneously, all of which are starting to think of Asia as a coherent whole. The other big stories will be the economic and social changes that China, India and Japan are all destined to go through during the next decade. Bill Emmott was the editor of The Economist from 1993 until March 31st 2006, the world's leading weekly magazine on current affairs and business. He has now stood down from that post to become an independent writer, speaker and consultant, based in London and Somerset. In 1980 he joined The Economist's Brussels office, writing about EEC affairs and the Benelux countries. In 1982 he became the paper's economics correspondent in London and the following year moved to Tokyo to cover Japan and South Korea.