Origin of the Long Head of Biceps Brachii from the Supraglenoid Tubercle and Glenoid Labrum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bone Limb Upper

Shoulder Pectoral girdle (shoulder girdle) Scapula Acromioclavicular joint proximal end of Humerus Clavicle Sternoclavicular joint Bone: Upper limb - 1 Scapula Coracoid proc. 3 angles Superior Inferior Lateral 3 borders Lateral angle Medial Lateral Superior 2 surfaces 3 processes Posterior view: Acromion Right Scapula Spine Coracoid Bone: Upper limb - 2 Scapula 2 surfaces: Costal (Anterior), Posterior Posterior view: Costal (Anterior) view: Right Scapula Right Scapula Bone: Upper limb - 3 Scapula Glenoid cavity: Glenohumeral joint Lateral view: Infraglenoid tubercle Right Scapula Supraglenoid tubercle posterior anterior Bone: Upper limb - 4 Scapula Supraglenoid tubercle: long head of biceps Anterior view: brachii Right Scapula Bone: Upper limb - 5 Scapula Infraglenoid tubercle: long head of triceps brachii Anterior view: Right Scapula (with biceps brachii removed) Bone: Upper limb - 6 Posterior surface of Scapula, Right Acromion; Spine; Spinoglenoid notch Suprspinatous fossa, Infraspinatous fossa Bone: Upper limb - 7 Costal (Anterior) surface of Scapula, Right Subscapular fossa: Shallow concave surface for subscapularis Bone: Upper limb - 8 Superior border Coracoid process Suprascapular notch Suprascapular nerve Posterior view: Right Scapula Bone: Upper limb - 9 Acromial Clavicle end Sternal end S-shaped Acromial end: smaller, oval facet Sternal end: larger,quadrangular facet, with manubrium, 1st rib Conoid tubercle Trapezoid line Right Clavicle Bone: Upper limb - 10 Clavicle Conoid tubercle: inferior -

Analysis on the Acromial Curvature and Its Relationships with The

r e v b r a s o r t o p . 2 0 1 4;4 9(6):636–641 www.rbo.org.br Original article Analysis on the acromial curvature and its relationships with the subacromial space and ଝ,ଝଝ types of acromion a,b,∗ c José Aderval Aragão , Leonardo Passos Silva , b a Francisco Prado Reis , Camilla Sá dos Santos Menezes a Department of Morphology, Universidade Federal de Sergipe (UFS), Aracaju, SE, Brazil b Medical School, Universidade Tiradentes (UNIT), Aracaju, SE, Brazil c Orthopedics and Traumatology Service, Hospital Santa Casa de Belo Horizonte, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Objective: To correlate the acromial curvature, using the angles proposed, with the subacro- Received 13 September 2013 mial space and types of acromion. Accepted 24 October 2013 Methods: Ninety scapulas were studied. The acromia were classified as types I, II or III. The Available online 31 October 2014 acromial curvature was analyzed by means of the alpha, beta and theta angles. We also measured the distance between the anteroinferior extremity of the acromion and the supra- Keywords: glenoid tubercle (DA). The scapulas were grouped in relation to sex and age. The angles proposed were analyzed in relation to each type of acromion and also in relation to the Acromion/anatomy & histology Shoulder collision syndrome measurements of the distance DA. Rotator cuff Results: Out of the total number of acromia, 39 (43.3%) were type I, 43 (47.7%) type II and eight (9%) type III. -

Anatomy and Physiology II

Anatomy and Physiology II Review Bones of the Upper Extremities Muscles of the Upper Extremities Anatomy and Physiology II Review Bones of the Upper Extremities Questions From Shoulder Girdle Lecture • Can you name the following structures? A – F • Acromion F – B B • Spine of the Scapula G – C • Medial (Vertebral) Border H – E C • Lateral (Axillary) Border – A • Superior Angle E I – D • Inferior Angle – G • Head of the Humerus D – H • Greater Tubercle of Humerus – I • Deltoid Tuberosity Questions From Shoulder Girdle Lecture • Would you be able to find the many of the same landmarks on this view (angles, borders, etc)? A • Can you name the following? – D • Coracoid process of scapula C – C D B • Lesser Tubercle – A • Greater Tubercle – B • Bicipital Groove (Intertubercular groove) Questions From Upper Extremities Lecture • Can you name the following structures? – B • Lateral epicondyle – A • Medial epicondyle A B Questions From Upper Extremities Lecture • Can you name the following landmarks? – C • Olecranon process – A • Head of the radius – B D • Medial epicondyle B A – D C • Lateral epicondyle Questions From Upper Extremities Lecture • Can you name the following bones and landmarks? – Which bone is A pointing to? • Ulna – Which bone is B pointing A to? • Radius E – C B • Styloid process of the ulna – D • Styloid process of the radius C – E D • Interosseous membrane of forearm Questions From Upper Extremities Lecture • Can you name the following bony landmarks? – Which landmark is A pointing to? • Lateral epicondyle of humerus – Which -

Morphometric Evaluation of Adult Acromion Process in North Indian Population Anatomy Section

Original Article DOI: 10.7860/JCDR/2017/21060.9312 Morphometric Evaluation of Adult Acromion Process in North Indian Population Anatomy Section SUSMITA SAHA1, NEELAM VASUDEva2 ABSTRACT distance and acromio-glenoid (Ac-g) distance were measured. Introduction: Dimensions of acromion process are important The measurements were compared with other osteological to show linkage to the shoulder girdle pathologies. Also studies performed on different population group. Data was morphometric analysis of acromion process would be helpful analysed using SPSS version 12.0 and mean values with for surgeons while performing surgical procedures on the standard deviation for each dimension were presented. shoulder joint. Results: The mean values of each measurement were: length: Aim: The purpose of this present study was to observe the 41.007 mm; width: 21.82 mm; thickness: 6.58 mm; C-A distance: detailed morphometric evaluation of adult acromion processes 28.34 mm and Ac-g distance: 26.21 mm. in North Indian population because different morphometric Conclusion: It is expected that various dimensions of adult dimensions play an important role in various disorders of the acromion process will serve as a reference base and will assist shoulder, particularly sub acromial impingement syndrome. the surgeon in the approach to be used and precision of the Materials and Methods: Two hundred adult dry scapulae from operative technique. So, the study will provide a vital support the osteology museum of MAMC, New Delhi, were obtained for for planning and executing acromioplasty in the treatment of evaluation of various measurement of acromion process. The impingement syndrome. length, width, thickness of acromion, coraco-acromial (C-A) Keywords: Acromioplasty, Morphometry, Scapula, Subacromial impingement syndrome INTRODUCTION was only 2.6% along with the three types of acromion process The acromion process projects forward almost at right angles, as described by Bigliani et al. -

Tutorial Article Imaging of the Shoulder W

EQUINE VETERINARY EDUCATION / AE / april 2010 199 Tutorial Article Imaging of the shoulder W. R. Redding* and A. P. Pease† Department of Clinical Sciences; and †Department of Molecular Biomedical Sciences, College of Veterinary Medicine, North Carolina State University, 4700 Hillsborough Street, Raleigh, North Carolina 27606, USA.eve_55 199..209 Keywords: horse; lameness; shoulder; ultrasonography; radiology Summary be performed before intra-articular anaesthesia to determine if effusion is present in the joint and to assist with Diagnosis of lameness associated with the shoulder region directing the placement of the needle into the shoulder requires a careful clinical examination, the use of joint. specifically placed intra-articular analgesia and a This paper discusses the normal anatomy as well as the combination of some common imaging techniques to radiographic and ultrasonographic examination of the accurately define the source of pain. Most equine shoulder area. In addition, reference to the use of nuclear practices performing lameness examinations in the horse scintigraphy and the benefits to help localise lesions to the have the radiographic and ultrasonographic equipment shoulder is discussed. necessary to accurately image the shoulder. This article presents a description of the unique anatomy of the Normal anatomy of the shoulder region shoulder and the specific application of radiographic and ultrasonographic techniques to provide a complete set of The most proximal joint in the appendicular skeleton of the diagnostic images of the shoulder region. A brief discussion forelimb is the scapulohumeral joint. It is composed of 2 of nuclear scintigraphy of this region is also included. bones, the distal end of the scapula and the proximal humerus (Sisson 1975). -

A Morphometric Study of the Patterns and Variations of the Acromion and Glenoid Cavity of the Scapulae in Egyptian Population Anatomy Section

Original Article DOI: 10.7860/JCDR/2015/14362.6386 A Morphometric Study of the Patterns and Variations of the Acromion and Glenoid Cavity of the Scapulae in Egyptian Population Anatomy Section WAEL AMIN NASR EL-DIN1, MONA HASSAN MOHAMMED ALI2 ABSTRACT were analysed using an unpaired t-test. Statistical significance Background: Owing to its many variations, scapula became was set p≤ 0.05. one of the most interesting bones of the human skeleton. Results: The intermediate shape of the acromion presented with Aim: To measure acromial and glenoid morphology in to the highest incidence, while the cobra shaped presented with describe their anatomical patterns and variations in Egyptians the lowest distribution in both sides. The oval shaped glenoid to establish possible morphofunctional correlations related to cavity presented with the highest incidence while the inverted race, geographic region and literature data. coma shaped showed the lowest incidence. Materials and Methods: One hundred and sixty scapulae of These results are in match with other population. However, unknown age and sex were studied. Morphological shapes of the morphometric values of the scapula, acromion process the tip of the acromion; types of acromion; and morphological and glenoid cavity were higher than reported in Turkish and shapes of the glenoid were evaluated. Length and width of Indians. the scapulae, length, breadth and thickness of the acromion Conclusion: Our data are important to compare Egyptian process and distances of the acromio-coracoid and acromio- scapulae to those from various other races that could contribute glenoid in addition to glenoid diameters were measured. to demographic studies of shoulder disease probability and Statistical Analysis: The morphometric values of the two sides management in Egyptian population. -

Angle of Approach to the Superior Rotator Cuff of Arthroscopic Instruments Depends on the Acromial Morphology: an Experimental Study in 3D Printed Human Shoulders

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2019 Angle of approach to the superior rotator cuff of arthroscopic instruments depends on the acromial morphology: an experimental study in 3D printed human shoulders Hoessly, Menduri ; Bouaicha, Samy ; Jentzsch, Thorsten ; Meyer, Dominik C Abstract: BACKGROUND Portal placement is a key factor for the success of arthroscopic procedures, particularly in rotator cuff repair. We hypothesize that the acromial anatomy may strongly determine the position of the shoulder bony landmarks and limit the surgeon’s freedom to position the arthroscopic approaches in direction towards the acromion. The purpose of this study was to analyze the relation between different acromial shapes and the freedom of movement of arthroscopic instruments relative to the rotator cuff from standardized arthroscopic portals in a laboratory study on 3D shoulder models. METHODS 3D models of shoulders with a broad range of different acromial shapes were printed using CT and MRI scans. Angles from the portals to defined points on the rotator cuff and the supraglenoid tubercle were measured. In conventional radiographs, the critical shoulder angle, the scapular body acromial angle, and the glenoid acromial angle were measured and compared with the measured angles to the rotator cuff. RESULTS There was a large variation of angles of approach of instruments tothe rotator cuff between the seven shoulders for each portal. From the joint line portal and the posterior edge portal, the biggest angles were measured to the posterior cuff. From the intermediate portal, the angles were largest to the intermediate rotator cuff and from the anterior portals to the anterior cuff. -

The Elbow and Radioulnar Joints

6/5/2017 The Elbow and Radioulnar Joints Bones Humerus trochlea of the humerus capitulum: spherical knob on lateral side medial and lateral epicondyle Ulnar Trochlear notch of ulna Olecranon Process on posterior aspect radial notch coronoid process ulnar tuberosity Radius Head radial tuberosity The Elbow Joint Classified as a ginglymus (hinge) joint The ELBOW consists of 2 joints: humeroulnar olecranon process of the ulnar distal aspect of humerus radiohumeral radial head has small amount of articulation with humerus (capitulum) 1 6/5/2017 Proximal Radioulnar Joint Proximal radioulnar joint articulation between radius and ulnar not part of “hinge” joint trochoid (pivot) joint allows for forearm pronation/supination Movements Elbow Flexion Extension Forearm movements about the Proximal Radioulnar joint Supination: Lateral rotation Pronation: Medial Rotation Muscles Anterior Posterior Biceps brachii Triceps brachii Brachialis Anconeus Brachioradialis Supinator Pronator teres Pronator quadratus 2 6/5/2017 Muscles Elbow Flexors biceps brachii brachialis brachioradialis pronator teres Muscles Elbow Extensors triceps brachii anconeus Forearm Pronators pronator teres pronator quadratus brachioradialis* Muscles Forarm Supinators supinator biceps brachii brachioradialis* 3 6/5/2017 Anconeus (p56) Origin posterior surface of lateral epicondyle of humerus Insertion ulna, posterior surface of olecranon process Action elbow extension Biceps Brachii (p 57) Origin: long head: supraglenoid tubercle -

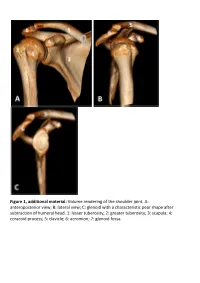

Glenoid with a Characteristic Pear Shape After Subtraction of Humeral Head

Figure 1, additional material: Volume rendering of the shoulder joint. A: anteroposterior view; B: lateral view; C: glenoid with a characteristic pear shape after subtraction of humeral head. 1: lesser tuberosity; 2: greater tuberosity; 3: scapula; 4: coracoid process; 5: clavicle; 6: acromion; 7: glenoid fossa. Figure 2, additional material: Schematic illustration of simplified shoulder anatomy. LHBT: Long head of biceps tendon; SGHL: Superior glenohumeral ligament. Trapezoid ligament and conoid ligament forming the coracoclavicular ligament. Figure 3, additional material: (A) axial, (B) sagittal oblique and (C) coronal oblique MR anatomy of the shoulder. PD-weighted sections obtained with 3 Tesla device. 1: Acromion, 2: Clavicle, 3: Acromioclavicular joint, 4: Lesser tuberosity, 5: Greater tuberosity, 6: Bicipital groove, 7: Anatomical neck, 8: Glenoid fossa/glenohumeral joint, 9: Scapula, 10: Scapular neck, 11: Suprascapular notch, 12: Coracoid process, 13: Deltoid, 14: Infraspinatus muscle, 15: Subscapularis muscle, 16: Subscapularis tendon, 17: Teres minor tendon, 18: Long head of biceps tendon, 19: Anterior labrum, 20: Posterior labrum, 21: Middle glenohumeral ligament, 22: Suprascapular nerve, 23: Inferior glenohumeral ligament/capsule, 24: Teres minor muscle, 25: Rib, 26: Humeral diaphysis, 27: Supraspinatus tendon, 28: Infraspinatus tendon, 29: Long head of biceps muscle, 30: Lateral head of triceps muscle, 31: Coracoacromial ligament, 32: Subacromial bursa, 33: Humeral head, 34: Pectoralis major muscle, 35: Coracobrachialis -

Radiographic Interpretation of the Canine Shoulder

PROCEDURES PRO h ORTHOPEDICS/DIAGNOSTIC IMAGING h PEER REVIEWED Radiographic Interpretation of the Canine Shoulder Ryan King, DVM, DACVR Stacie Aarsvold, DVM Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine, Tufts University d FIGURE 1 Lateral radiograph of a normal shoulder showing the biceps origin (blue circle) and course (blue bar) Shoulder lameness is common in juvenile and adult fibrous joint capsule. The adjacent musculature stabi- dogs. Lameness may be caused by degenerative, infec- lizes the joint and extends and/or flexes the thoracic tious, neoplastic, or developmental growth disorders. limb. The joint is extended by the supraspinatus and Radiographically identifying lesions can help clinicians infraspinatus muscles and flexed by the triceps muscle, categorize associated conditions. with concurrent flexion and extension of the elbow by the biceps and triceps muscles, respectively.1 A complete radiographic series, including lateral, caudocranial +/- cranioproximal–craniodistal oblique The proximal biceps tendon originates from the supra- (skyline) views, should be obtained when evaluating glenoid tubercle and traverses the cranial aspect of patients with shoulder lameness. Accurate diagnosis the proximal humerus in the intertubercular groove, requires radiographs that are correctly positioned and where, at the musculotendinous junction, it forms the exposed. Sedation is recommended for patients under- biceps muscle. Mineralization may occur at any point going orthopedic radiography. along the length of the tendon but is commonly noted both superimposed with the groove and at the tendon Anatomy origin (Figure 1).1 Before radiography, the clinician should review the anatomy of the canine shoulder. The shoulder consists The supraspinatus tendon is a broad tendon that arises of a simple ball-and-socket joint between the humeral from the supraspinatus muscle and is attached to the head and the glenoid cavity and is surrounded by a lateral aspect of the greater tubercle. -

Lab Activity 9

Lab Activity 9 Appendicular Skeleton Martini Chapter 8 Portland Community College BI 231 Appendicular Skeleton • Upper & Lower extremities • Shoulder Girdle • Pelvic Girdle 2 Humerus 3 Humerus: Proximal End Greater tubercle Lesser tubercle Head: Above the epiphyseal line Anatomical Neck Surgical neck Intertubercular groove Anterior Medial Posterior4 Deltoid Tuberosity 5 Radial Groove 6 Trochlea (Distal Humerus) Anterior Posterior Anterior Posterior 7 Capitulum (Distal Humerus) Anterior Posterior Anterior Posterior 8 Olecranon Fossa (Distal Humerus) Anterior Posterior Anterior Posterior 9 Medial Epicondyle (Distal Humerus) Anterior Posterior Anterior Posterior 10 Lateral Epicondyle (Distal Humerus) Anterior Posterior Anterior Posterior 11 Radial Fossa (Distal Humerus) Anterior Posterior Anterior Posterior 12 Coronoid Fossa (Distal Humerus) Anterior Posterior Anterior Posterior 13 Lateral Supracondylar Ridge (Distal Humerus) Anterior Posterior Anterior Posterior 14 Medial Supracondylar Ridge (Distal Humerus) Anterior Posterior Anterior Posterior 15 Humerus: Distal End/Anterior Medial Lateral Supracondylar Supracondylar Ridge Ridge Coronoid Fossa Radial fossa Lateral Medial Epicondyle Epicondyle Capitulum Trochlea 16 Humerus: Distal End/Posterior Olecranon Fossa Medial Epicondyle Lateral Epicondyle Trochlea 17 Radius • “Rotates” • On the thumb side of the forearm 18 Radius: Head 19 Radial Tuberosity 20 Ulnar Notch of the Radius 21 Ulnar Notch of the Radius 22 Radius: Interosseous Ridge 23 Styloid Process of the Radius 24 Radius Distal Anterior -

Functional Anatomy of the Shoulder Glenn C

Journal ofAthletic Training 2000;35(3):248-255 C) by the National Athletic Trainers' Association, Inc www.journalofathletictraining.org Functional Anatomy of the Shoulder Glenn C. Terry, MD; Thomas M. Chopp, MD The Hughston Clinic, Columbus, GA Objective: Movements of the human shoulder represent the nents. Bony anatomy, including the humerus, scapula, and result of a complex dynamic interplay of structural bony anat- clavicle, is described, along with the associated articulations, omy and biomechanics, static ligamentous and tendinous providing the clinician with the structural foundation for under- restraints, and dynamic muscle forces. Injury to 1 or more of standing how the static ligamentous and dynamic muscle these components through overuse or acute trauma disrupts forces exert their effects. Commonly encountered athletic inju- this complex interrelationship and places the shoulder at in- ries are discussed from an anatomical standpoint. creased risk. A thorough understanding of the functional anat- Conclusions/Recommendations: Shoulder injuries repre- omy of the shoulder provides the clinician with a foundation for sent a significant proportion of athletic injuries seen by the caring for athletes with shoulder injuries. medical provider. A functional understanding of the dynamic Data Sources: We searched MEDLINE for the years 1980 to interplay of biomechanical forces around the shoulder girdle is 1999, using the key words "shoulder," "anatomy," "glenohu- necessary and allows for a more structured approach to the meral joint," "acromioclavicular joint," "sternoclavicular joint," treatment of an athlete with a shoulder injury. "scapulothoracic joint," and "rotator cuff." Key Words: anatomy, static, dynamic, stability, articulation Data Synthesis: We examine human shoulder movement by breaking it down into its structural static and dynamic compo- M ovements of the human shoulder represent a complex BONY ANATOMY dynamic relationship of many muscle forces, liga- ment constraints, and bony articulations.