Radiographic Interpretation of the Canine Shoulder

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Body Mechanics As the Rotator Cuff Gether in a Cuff-Shape Across the Greater and Lesser Tubercles the on Head of the Humerus

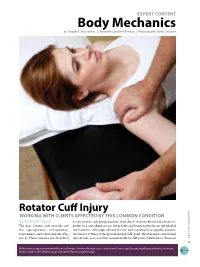

EXPerT CONTENT Body Mechanics by Joseph E. Muscolino | Artwork Giovanni Rimasti | Photography Yanik Chauvin Rotator Cuff Injury www.amtamassage.org/mtj WORKING WITH CLieNTS AFFecTED BY THIS COmmON CONDITION ROTATOR CUFF GROUP as the rotator cuff group because their distal tendons blend and attach to- The four rotator cuff muscles are gether in a cuff-shape across the greater and lesser tubercles on the head of the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, the humerus. Although all four rotator cuff muscles have specific concen- teres minor, and subscapularis (Fig- tric mover actions at the glenohumeral (GH) joint, their primary functional ure 1). These muscles are described importance is to contract isometrically for GH joint stabilization. Because 17 Before practicing any new modality or technique, check with your state’s or province’s massage therapy regulatory authority to ensure that it is within the defined scope of practice for massage therapy. the rotator cuff group has both mover and stabilization roles, it is extremely functionally active and therefore often physically stressed and injured. In fact, after neck and low back conditions, the shoulder is the most com- Supraspinatus monly injured joint of the human body. ROTATOR CUFF PATHOLOGY The three most common types of rotator cuff pathology are tendinitis, tendinosus, and tearing. Excessive physi- cal stress placed on the rotator cuff tendon can cause ir- ritation and inflammation of the tendon, in other words, tendinitis. If the physical stress is chronic, the inflam- matory process often subsides and degeneration of the fascial tendinous tissue occurs; this is referred to as tendinosus. The degeneration of tendinosus results in weakness of the tendon’s structure, and with continued Teres minor physical stress, whether it is overuse microtrauma or a macrotrauma, a rotator cuff tendon tear might occur. -

Should Joint Presentation File

6/5/2017 The Shoulder Joint Bones of the shoulder joint • Scapula – Glenoid Fossa Infraspinatus fossa – Supraspinatus fossa Subscapular fossa – Spine Coracoid process – Acromion process • Clavicle • Humerus – Greater tubercle Lesser tubercle – Intertubercular goove Deltoid tuberosity – Head of Humerus Shoulder Joint • Bones: – humerus – scapula Shoulder Girdle – clavicle • Articulation – glenohumeral joint • Glenoid fossa of the scapula (less curved) • head of the humerus • enarthrodial (ball and socket) 1 6/5/2017 Shoulder Joint • Connective tissue – glenoid labrum: cartilaginous ring, surrounds glenoid fossa • increases contact area between head of humerus and glenoid fossa. • increases joint stability – Glenohumeral ligaments: reinforce the glenohumeral joint capsule • superior, middle, inferior (anterior side of joint) – coracohumeral ligament (superior) • Muscles play a crucial role in maintaining glenohumeral joint stability. Movements of the Shoulder Joint • Arm abduction, adduction about the shoulder • Arm flexion, extension • Arm hyperflexion, hyperextension • Arm horizontal adduction (flexion) • Arm horizontal abduction (extension) • Arm external and internal rotation – medial and lateral rotation • Arm circumduction – flexion, abduction, extension, hyperextension, adduction Scapulohumeral rhythm • Shoulder Joint • Shoulder Girdle – abduction – upward rotation – adduction – downward rotation – flexion – elevation/upward rot. – extension – Depression/downward rot. – internal rotation – Abduction (protraction) – external rotation -

Bone Limb Upper

Shoulder Pectoral girdle (shoulder girdle) Scapula Acromioclavicular joint proximal end of Humerus Clavicle Sternoclavicular joint Bone: Upper limb - 1 Scapula Coracoid proc. 3 angles Superior Inferior Lateral 3 borders Lateral angle Medial Lateral Superior 2 surfaces 3 processes Posterior view: Acromion Right Scapula Spine Coracoid Bone: Upper limb - 2 Scapula 2 surfaces: Costal (Anterior), Posterior Posterior view: Costal (Anterior) view: Right Scapula Right Scapula Bone: Upper limb - 3 Scapula Glenoid cavity: Glenohumeral joint Lateral view: Infraglenoid tubercle Right Scapula Supraglenoid tubercle posterior anterior Bone: Upper limb - 4 Scapula Supraglenoid tubercle: long head of biceps Anterior view: brachii Right Scapula Bone: Upper limb - 5 Scapula Infraglenoid tubercle: long head of triceps brachii Anterior view: Right Scapula (with biceps brachii removed) Bone: Upper limb - 6 Posterior surface of Scapula, Right Acromion; Spine; Spinoglenoid notch Suprspinatous fossa, Infraspinatous fossa Bone: Upper limb - 7 Costal (Anterior) surface of Scapula, Right Subscapular fossa: Shallow concave surface for subscapularis Bone: Upper limb - 8 Superior border Coracoid process Suprascapular notch Suprascapular nerve Posterior view: Right Scapula Bone: Upper limb - 9 Acromial Clavicle end Sternal end S-shaped Acromial end: smaller, oval facet Sternal end: larger,quadrangular facet, with manubrium, 1st rib Conoid tubercle Trapezoid line Right Clavicle Bone: Upper limb - 10 Clavicle Conoid tubercle: inferior -

Trapezius Origin: Occipital Bone, Ligamentum Nuchae & Spinous Processes of Thoracic Vertebrae Insertion: Clavicle and Scapul

Origin: occipital bone, ligamentum nuchae & spinous processes of thoracic vertebrae Insertion: clavicle and scapula (acromion Trapezius and scapular spine) Action: elevate, retract, depress, or rotate scapula upward and/or elevate clavicle; extend neck Origin: spinous process of vertebrae C7-T1 Rhomboideus Insertion: vertebral border of scapula Minor Action: adducts & performs downward rotation of scapula Origin: spinous process of superior thoracic vertebrae Rhomboideus Insertion: vertebral border of scapula from Major spine to inferior angle Action: adducts and downward rotation of scapula Origin: transverse precesses of C1-C4 vertebrae Levator Scapulae Insertion: vertebral border of scapula near superior angle Action: elevates scapula Origin: anterior and superior margins of ribs 1-8 or 1-9 Insertion: anterior surface of vertebral Serratus Anterior border of scapula Action: protracts shoulder: rotates scapula so glenoid cavity moves upward rotation Origin: anterior surfaces and superior margins of ribs 3-5 Insertion: coracoid process of scapula Pectoralis Minor Action: depresses & protracts shoulder, rotates scapula (glenoid cavity rotates downward), elevates ribs Origin: supraspinous fossa of scapula Supraspinatus Insertion: greater tuberacle of humerus Action: abduction at the shoulder Origin: infraspinous fossa of scapula Infraspinatus Insertion: greater tubercle of humerus Action: lateral rotation at shoulder Origin: clavicle and scapula (acromion and adjacent scapular spine) Insertion: deltoid tuberosity of humerus Deltoid Action: -

Analysis on the Acromial Curvature and Its Relationships with The

r e v b r a s o r t o p . 2 0 1 4;4 9(6):636–641 www.rbo.org.br Original article Analysis on the acromial curvature and its relationships with the subacromial space and ଝ,ଝଝ types of acromion a,b,∗ c José Aderval Aragão , Leonardo Passos Silva , b a Francisco Prado Reis , Camilla Sá dos Santos Menezes a Department of Morphology, Universidade Federal de Sergipe (UFS), Aracaju, SE, Brazil b Medical School, Universidade Tiradentes (UNIT), Aracaju, SE, Brazil c Orthopedics and Traumatology Service, Hospital Santa Casa de Belo Horizonte, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Objective: To correlate the acromial curvature, using the angles proposed, with the subacro- Received 13 September 2013 mial space and types of acromion. Accepted 24 October 2013 Methods: Ninety scapulas were studied. The acromia were classified as types I, II or III. The Available online 31 October 2014 acromial curvature was analyzed by means of the alpha, beta and theta angles. We also measured the distance between the anteroinferior extremity of the acromion and the supra- Keywords: glenoid tubercle (DA). The scapulas were grouped in relation to sex and age. The angles proposed were analyzed in relation to each type of acromion and also in relation to the Acromion/anatomy & histology Shoulder collision syndrome measurements of the distance DA. Rotator cuff Results: Out of the total number of acromia, 39 (43.3%) were type I, 43 (47.7%) type II and eight (9%) type III. -

Anatomy and Physiology II

Anatomy and Physiology II Review Bones of the Upper Extremities Muscles of the Upper Extremities Anatomy and Physiology II Review Bones of the Upper Extremities Questions From Shoulder Girdle Lecture • Can you name the following structures? A – F • Acromion F – B B • Spine of the Scapula G – C • Medial (Vertebral) Border H – E C • Lateral (Axillary) Border – A • Superior Angle E I – D • Inferior Angle – G • Head of the Humerus D – H • Greater Tubercle of Humerus – I • Deltoid Tuberosity Questions From Shoulder Girdle Lecture • Would you be able to find the many of the same landmarks on this view (angles, borders, etc)? A • Can you name the following? – D • Coracoid process of scapula C – C D B • Lesser Tubercle – A • Greater Tubercle – B • Bicipital Groove (Intertubercular groove) Questions From Upper Extremities Lecture • Can you name the following structures? – B • Lateral epicondyle – A • Medial epicondyle A B Questions From Upper Extremities Lecture • Can you name the following landmarks? – C • Olecranon process – A • Head of the radius – B D • Medial epicondyle B A – D C • Lateral epicondyle Questions From Upper Extremities Lecture • Can you name the following bones and landmarks? – Which bone is A pointing to? • Ulna – Which bone is B pointing A to? • Radius E – C B • Styloid process of the ulna – D • Styloid process of the radius C – E D • Interosseous membrane of forearm Questions From Upper Extremities Lecture • Can you name the following bony landmarks? – Which landmark is A pointing to? • Lateral epicondyle of humerus – Which -

Morphometric Evaluation of Adult Acromion Process in North Indian Population Anatomy Section

Original Article DOI: 10.7860/JCDR/2017/21060.9312 Morphometric Evaluation of Adult Acromion Process in North Indian Population Anatomy Section SUSMITA SAHA1, NEELAM VASUDEva2 ABSTRACT distance and acromio-glenoid (Ac-g) distance were measured. Introduction: Dimensions of acromion process are important The measurements were compared with other osteological to show linkage to the shoulder girdle pathologies. Also studies performed on different population group. Data was morphometric analysis of acromion process would be helpful analysed using SPSS version 12.0 and mean values with for surgeons while performing surgical procedures on the standard deviation for each dimension were presented. shoulder joint. Results: The mean values of each measurement were: length: Aim: The purpose of this present study was to observe the 41.007 mm; width: 21.82 mm; thickness: 6.58 mm; C-A distance: detailed morphometric evaluation of adult acromion processes 28.34 mm and Ac-g distance: 26.21 mm. in North Indian population because different morphometric Conclusion: It is expected that various dimensions of adult dimensions play an important role in various disorders of the acromion process will serve as a reference base and will assist shoulder, particularly sub acromial impingement syndrome. the surgeon in the approach to be used and precision of the Materials and Methods: Two hundred adult dry scapulae from operative technique. So, the study will provide a vital support the osteology museum of MAMC, New Delhi, were obtained for for planning and executing acromioplasty in the treatment of evaluation of various measurement of acromion process. The impingement syndrome. length, width, thickness of acromion, coraco-acromial (C-A) Keywords: Acromioplasty, Morphometry, Scapula, Subacromial impingement syndrome INTRODUCTION was only 2.6% along with the three types of acromion process The acromion process projects forward almost at right angles, as described by Bigliani et al. -

Tutorial Article Imaging of the Shoulder W

EQUINE VETERINARY EDUCATION / AE / april 2010 199 Tutorial Article Imaging of the shoulder W. R. Redding* and A. P. Pease† Department of Clinical Sciences; and †Department of Molecular Biomedical Sciences, College of Veterinary Medicine, North Carolina State University, 4700 Hillsborough Street, Raleigh, North Carolina 27606, USA.eve_55 199..209 Keywords: horse; lameness; shoulder; ultrasonography; radiology Summary be performed before intra-articular anaesthesia to determine if effusion is present in the joint and to assist with Diagnosis of lameness associated with the shoulder region directing the placement of the needle into the shoulder requires a careful clinical examination, the use of joint. specifically placed intra-articular analgesia and a This paper discusses the normal anatomy as well as the combination of some common imaging techniques to radiographic and ultrasonographic examination of the accurately define the source of pain. Most equine shoulder area. In addition, reference to the use of nuclear practices performing lameness examinations in the horse scintigraphy and the benefits to help localise lesions to the have the radiographic and ultrasonographic equipment shoulder is discussed. necessary to accurately image the shoulder. This article presents a description of the unique anatomy of the Normal anatomy of the shoulder region shoulder and the specific application of radiographic and ultrasonographic techniques to provide a complete set of The most proximal joint in the appendicular skeleton of the diagnostic images of the shoulder region. A brief discussion forelimb is the scapulohumeral joint. It is composed of 2 of nuclear scintigraphy of this region is also included. bones, the distal end of the scapula and the proximal humerus (Sisson 1975). -

Chapter 5 the Shoulder Joint

The Shoulder Joint • Shoulder joint is attached to axial skeleton via the clavicle at SC joint • Scapula movement usually occurs with movement of humerus Chapter 5 – Humeral flexion & abduction require scapula The Shoulder Joint elevation, rotation upward, & abduction – Humeral adduction & extension results in scapula depression, rotation downward, & adduction Manual of Structural Kinesiology – Scapula abduction occurs with humeral internal R.T. Floyd, EdD, ATC, CSCS rotation & horizontal adduction – Scapula adduction occurs with humeral external rotation & horizontal abduction © McGraw-Hill Higher Education. All rights reserved. 5-1 © McGraw-Hill Higher Education. All rights reserved. 5-2 The Shoulder Joint Bones • Wide range of motion of the shoulder joint in • Scapula, clavicle, & humerus serve as many different planes requires a significant attachments for shoulder joint muscles amount of laxity – Scapular landmarks • Common to have instability problems • supraspinatus fossa – Rotator cuff impingement • infraspinatus fossa – Subluxations & dislocations • subscapular fossa • spine of the scapula • The price of mobility is reduced stability • glenoid cavity • The more mobile a joint is, the less stable it • coracoid process is & the more stable it is, the less mobile • acromion process • inferior angle © McGraw-Hill Higher Education. All rights reserved. 5-3 © McGraw-Hill Higher Education. All rights reserved. From Seeley RR, Stephens TD, Tate P: Anatomy and physiology , ed 7, 5-4 New York, 2006, McGraw-Hill Bones Bones • Scapula, clavicle, & humerus serve as • Key bony landmarks attachments for shoulder joint muscles – Acromion process – Humeral landmarks – Glenoid fossa • Head – Lateral border • Greater tubercle – Inferior angle • Lesser tubercle – Medial border • Intertubercular groove • Deltoid tuberosity – Superior angle – Spine of the scapula © McGraw-Hill Higher Education. -

A Morphometric Study of the Patterns and Variations of the Acromion and Glenoid Cavity of the Scapulae in Egyptian Population Anatomy Section

Original Article DOI: 10.7860/JCDR/2015/14362.6386 A Morphometric Study of the Patterns and Variations of the Acromion and Glenoid Cavity of the Scapulae in Egyptian Population Anatomy Section WAEL AMIN NASR EL-DIN1, MONA HASSAN MOHAMMED ALI2 ABSTRACT were analysed using an unpaired t-test. Statistical significance Background: Owing to its many variations, scapula became was set p≤ 0.05. one of the most interesting bones of the human skeleton. Results: The intermediate shape of the acromion presented with Aim: To measure acromial and glenoid morphology in to the highest incidence, while the cobra shaped presented with describe their anatomical patterns and variations in Egyptians the lowest distribution in both sides. The oval shaped glenoid to establish possible morphofunctional correlations related to cavity presented with the highest incidence while the inverted race, geographic region and literature data. coma shaped showed the lowest incidence. Materials and Methods: One hundred and sixty scapulae of These results are in match with other population. However, unknown age and sex were studied. Morphological shapes of the morphometric values of the scapula, acromion process the tip of the acromion; types of acromion; and morphological and glenoid cavity were higher than reported in Turkish and shapes of the glenoid were evaluated. Length and width of Indians. the scapulae, length, breadth and thickness of the acromion Conclusion: Our data are important to compare Egyptian process and distances of the acromio-coracoid and acromio- scapulae to those from various other races that could contribute glenoid in addition to glenoid diameters were measured. to demographic studies of shoulder disease probability and Statistical Analysis: The morphometric values of the two sides management in Egyptian population. -

Axial Skeleton List for API

Axial Skeleton List for API Sutures Coronal Lambdoidal Squamous Sagittal Bones of the Skull Frontal Bone Parietal Bone Temporal Bone Occipital Bone Zygomatic Bone Zygomatic Arch Zygomatic Process Mandible (mental foramen) Maxilla Nasal Bone Vomer Bone Ethmoid Bone (Crista galli) Foramen magnum Sella turcica External auditory (acoustic) meatus Mastoid Process Styloid Process Superior nuchal line Inferior nuchal line External occipital protuberance (EOP) Sternum (xyphoid process) Ribs Sacrum Coccyx Dr. Tarsha Smith Page 1 Axial Skeleton List for API (continued) Vertebrae Atlas (superior articular facet; posterior tubercle) Axis (dens or odontoid process) Cervical, Thoracic, Lumbar Know following terms on all vertebrae, if present: Facet, Pedicle, Spinous, Body, Transverse process, Lamina Appendicular Skeleton List for API Clavicle Conoid tubercle Scapula Acromion Medial border Coracoid process Lateral border Glenoid cavity Subscapular fossa Spine Infraspinous fossa Humerus Head Capitulum Surgical neck Trochlea Greater tubercle Olecranon fossa Lesser tubercle Coronoid fossa Epicondyles (lateral & medial) Radius Tuberosity of radius Articular facets Styloid process Head & neck Ulna Trochlear notch Radial notch of ulna Coronoid process Hand Phalanges Metacarpals Carpals: Scaphoid, Lunate, Triquetrium, Pisiform, Trapezium, Trapezoid, Capitate, Hamate Dr. Tarsha Smith Page 2 Appendicular Skeleton List for API (continued) Pelvis Ilium Crest Anterior superior Anterior inferior Ischium Body Ramus Spine Pubis Pubic symphysis Obturator foramen Acetabulum Femur Fovea capitis Greater trochanter Head Neck Lesser trochanter Linea aspera Epicondyles (medial & lateral) Condyles (medial & lateral) Intercondylar fossa Patella (kneecap) Tibia Condyle (medial & lateral) Tibial tuberosity Medial malleolus Fibula Lateral malleolus Apex Foot Metatarsals Phalanx Tarsals: Cuneiforms, Navicular, talus, cuboid, calcaneus Dr. Tarsha Smith Page 3 . -

Muscles of the Upper Limb.Pdf

11/8/2012 Muscles Stabilizing Pectoral Girdle Muscles of the Upper Limb Pectoralis minor ORIGIN: INNERVATION: anterior surface of pectoral nerves ribs 3 – 5 ACTION: INSERTION: protracts / depresses scapula coracoid process (scapula) (Anterior view) Muscles Stabilizing Pectoral Girdle Muscles Stabilizing Pectoral Girdle Serratus anterior Subclavius ORIGIN: INNERVATION: ORIGIN: INNERVATION: ribs 1 - 8 long thoracic nerve rib 1 ---------------- INSERTION: ACTION: INSERTION: ACTION: medial border of scapula rotates scapula laterally inferior surface of scapula stabilizes / depresses pectoral girdle (Lateral view) (anterior view) Muscles Stabilizing Pectoral Girdle Muscles Stabilizing Pectoral Girdle Trapezius Levator scapulae ORIGIN: INNERVATION: ORIGIN: INNERVATION: occipital bone / spinous accessory nerve transverse processes of C1 – C4 dorsal scapular nerve processes of C7 – T12 ACTION: INSERTION: ACTION: INSERTION: stabilizes / elevates / retracts / upper medial border of scapula elevates / adducts scapula acromion / spine of scapula; rotates scapula lateral third of clavicle (Posterior view) (Posterior view) 1 11/8/2012 Muscles Stabilizing Pectoral Girdle Muscles Moving Arm Rhomboids Pectoralis major (major / minor) ORIGIN: INNERVATION: ORIGIN: INNERVATION: spinous processes of C7 – T5 dorsal scapular nerve sternum / clavicle / ribs 1 – 6 dorsal scapular nerve INSERTION: ACTION: INSERTION: ACTION: medial border of scapula adducts / rotates scapula intertubucular sulcus / greater tubercle flexes / medially rotates / (humerus) adducts