Chronic Diseases in Canada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Characterising the Risk of Major Bleeding in Patients With

EU PE&PV Research Network under the Framework Service Contract (nr. EMA/2015/27/PH) Study Protocol Characterising the risk of major bleeding in patients with Non-Valvular Atrial Fibrillation: non-interventional study of patients taking Direct Oral Anticoagulants in the EU Version 3.0 1 June 2018 EU PAS Register No: 16014 EMA/2015/27/PH EUPAS16014 Version 3.0 1 June 2018 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Title ........................................................................................................................................... 5 2 Marketing authorization holder ................................................................................................. 5 3 Responsible parties ................................................................................................................... 5 4 Abstract ..................................................................................................................................... 6 5 Amendments and updates ......................................................................................................... 7 6 Milestones ................................................................................................................................. 8 7 Rationale and background ......................................................................................................... 9 8 Research question and objectives .............................................................................................. 9 9 Research methods .................................................................................................................... -

Reseptregisteret 2013–2017 the Norwegian Prescription Database

LEGEMIDDELSTATISTIKK 2018:2 Reseptregisteret 2013–2017 Tema: Legemidler og eldre The Norwegian Prescription Database 2013–2017 Topic: Drug use in the elderly Reseptregisteret 2013–2017 Tema: Legemidler og eldre The Norwegian Prescription Database 2013–2017 Topic: Drug use in the elderly Christian Berg Hege Salvesen Blix Olaug Fenne Kari Furu Vidar Hjellvik Kari Jansdotter Husabø Irene Litleskare Marit Rønning Solveig Sakshaug Randi Selmer Anne-Johanne Søgaard Sissel Torheim Utgitt av Folkehelseinstituttet/Published by Norwegian Institute of Public Health Område for Helsedata og digitalisering Avdeling for Legemiddelstatistikk Juni 2018 Tittel/Title: Legemiddelstatistikk 2018:2 Reseptregisteret 2013–2017 / The Norwegian Prescription Database 2013–2017 Forfattere/Authors: Christian Berg, redaktør/editor Hege Salvesen Blix Olaug Fenne Kari Furu Vidar Hjellvik Kari Jansdotter Husabø Irene Litleskare Marit Rønning Solveig Sakshaug Randi Selmer Anne-Johanne Søgaard Sissel Torheim Acknowledgement: Julie D. W. Johansen (English text) Bestilling/Order: Rapporten kan lastes ned som pdf på Folkehelseinstituttets nettsider: www.fhi.no The report can be downloaded from www.fhi.no Grafisk design omslag: Fete Typer Ombrekking: Houston911 Kontaktinformasjon/Contact information: Folkehelseinstituttet/Norwegian Institute of Public Health Postboks 222 Skøyen N-0213 Oslo Tel: +47 21 07 70 00 ISSN: 1890-9647 ISBN: 978-82-8082-926-9 Sitering/Citation: Berg, C (red), Reseptregisteret 2013–2017 [The Norwegian Prescription Database 2013–2017] Legemiddelstatistikk 2018:2, Oslo, Norge: Folkehelseinstituttet, 2018. Tidligere utgaver / Previous editions: 2008: Reseptregisteret 2004–2007 / The Norwegian Prescription Database 2004–2007 2009: Legemiddelstatistikk 2009:2: Reseptregisteret 2004–2008 / The Norwegian Prescription Database 2004–2008 2010: Legemiddelstatistikk 2010:2: Reseptregisteret 2005–2009. Tema: Vanedannende legemidler / The Norwegian Prescription Database 2005–2009. -

MIRADON FPO Brand of Anisindione Tablets

R 1 2 3 4 5 3 4 F-16099775 1898 ® MIRADON FPO brand of anisindione Tablets DESCRIPTION MIRADON Tablets contain a syn- thetic anticoagulant, anisindione, an indanedione derivative. Each tablet contains 50 mg anisin- dione. They also contain: corn starch, FD&C Red No. 3, gelatin, lactose, and hydrogenated cotton- seed oil. ACTIONS Like phenindione, to which it is re- lated chemically, anisindione exercises its thera- peutic action by reducing the prothrombin activity of the blood. INDICATIONS Anisindione is indicated for the prophylaxis and treatment of venous thrombosis and its extension, the treatment of atrial fibrilla- tion with embolization, the prophylaxis and treat- ment of pulmonary embolism, and as an adjunct in the treatment of coronary occlusion. CONTRAINDICATIONS All contraindications to oral anticoagulant therapy are relative rather than absolute. Contraindications should be evaluated for each patient, giving consideration to the need for and the benefits to be achieved by anticoagu- lant therapy, the potential dangers of hemor- rhage, the expected duration of therapy, and the quality of patient monitoring and compliance. Hemorrhagic Tendencies or Blood Dyscrasias: In general, oral anticoagulants are contraindi- cated in patients who are bleeding or who have hemorrhagic blood dyscrasias or hemorrhagic tendencies (eg, hemophilia, polycythemia vera, purpura, leukemia) or a history of bleeding dia- thesis. They are contraindicated in patients with recent cerebral hemorrhage, active ulceration of the gastrointestinal tract, including ulcerative colitis, or open ulcerative, traumatic, or surgical wounds. Oral anticoagulants may be contraindi- cated in patients with recent or contemplated brain, eye, or spinal cord surgery or prostatec- tomy, and in those undergoing regional or lumbar block anesthesia or continuous tube drainage of the small intestine. -

Oral Anticoagulants (VKA and DOAC) Guidelines for Prescribing, Monitoring and Management

Clinical Guidance Oral Anticoagulants (VKA and DOAC) Guidelines for prescribing, monitoring and management Anticoagulants are one of the classes of medicines which frequently cause harm and admission to hospital. Managing the risk associated with anticoagulants was the subject of The National Patient Safety Agency Patient Safety Alert number 18 March 2007. High risks identified with prescribing anticoagulation include: • Failure to initiate oral anticoagulant therapy where indicated • Poor documentation of reason and treatment plan at commencement of therapy • Incorrect prescribing of oral anticoagulant doses (especially loading doses) The formulary has 5 different anticoagulants to choose from. For the majority of patients, the choice of anticoagulant is guided by indication, clinician and patient choice after appropriate discussion of risks and benefits of the different options. Anticoagulation is not advisable if the risk of harm is likely to outweigh the benefits of treatment. Consideration should be given to the safety of initiating oral anticoagulants in patients with: • cognitive impairment • risk of falls/ with a history of falls, • history of bleeding, • excess alcohol intake • liver disease • impaired visual acuity The HASBLED score can be used to give an indication of the overall risk of bleeding. This scoring system has been validated in patients with atrial fibrillation (it is not validated in the VTE setting). Clinical characteristic Points awarded H Hypertension 1 A Abnormal renal and liver function (1 point each) 1 or 2 S Stroke 1 B Bleeding 1 L Labile INRs 1 E Elderly (age >65 years) 1 D Drugs or alcohol (1 point each) 1 or 2 Maximum 9 points A score of 3 or more indicates increased one year bleed risk on anticoagulation sufficient to justify caution or more regular review. -

![Ehealth DSI [Ehdsi V2.2.2-OR] Ehealth DSI – Master Value Set](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8870/ehealth-dsi-ehdsi-v2-2-2-or-ehealth-dsi-master-value-set-1028870.webp)

Ehealth DSI [Ehdsi V2.2.2-OR] Ehealth DSI – Master Value Set

MTC eHealth DSI [eHDSI v2.2.2-OR] eHealth DSI – Master Value Set Catalogue Responsible : eHDSI Solution Provider PublishDate : Wed Nov 08 16:16:10 CET 2017 © eHealth DSI eHDSI Solution Provider v2.2.2-OR Wed Nov 08 16:16:10 CET 2017 Page 1 of 490 MTC Table of Contents epSOSActiveIngredient 4 epSOSAdministrativeGender 148 epSOSAdverseEventType 149 epSOSAllergenNoDrugs 150 epSOSBloodGroup 155 epSOSBloodPressure 156 epSOSCodeNoMedication 157 epSOSCodeProb 158 epSOSConfidentiality 159 epSOSCountry 160 epSOSDisplayLabel 167 epSOSDocumentCode 170 epSOSDoseForm 171 epSOSHealthcareProfessionalRoles 184 epSOSIllnessesandDisorders 186 epSOSLanguage 448 epSOSMedicalDevices 458 epSOSNullFavor 461 epSOSPackage 462 © eHealth DSI eHDSI Solution Provider v2.2.2-OR Wed Nov 08 16:16:10 CET 2017 Page 2 of 490 MTC epSOSPersonalRelationship 464 epSOSPregnancyInformation 466 epSOSProcedures 467 epSOSReactionAllergy 470 epSOSResolutionOutcome 472 epSOSRoleClass 473 epSOSRouteofAdministration 474 epSOSSections 477 epSOSSeverity 478 epSOSSocialHistory 479 epSOSStatusCode 480 epSOSSubstitutionCode 481 epSOSTelecomAddress 482 epSOSTimingEvent 483 epSOSUnits 484 epSOSUnknownInformation 487 epSOSVaccine 488 © eHealth DSI eHDSI Solution Provider v2.2.2-OR Wed Nov 08 16:16:10 CET 2017 Page 3 of 490 MTC epSOSActiveIngredient epSOSActiveIngredient Value Set ID 1.3.6.1.4.1.12559.11.10.1.3.1.42.24 TRANSLATIONS Code System ID Code System Version Concept Code Description (FSN) 2.16.840.1.113883.6.73 2017-01 A ALIMENTARY TRACT AND METABOLISM 2.16.840.1.113883.6.73 2017-01 -

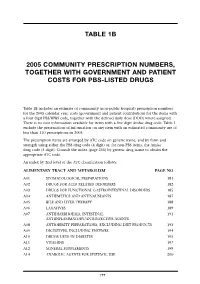

Table 1B 2005 Community Prescription Numbers, Together with Government

TABLE 1B 2005 COMMUNITY PRESCRIPTION NUMBERS, TOGETHER WITH GOVERNMENT AND PATIENT COSTS FOR PBS-LISTED DRUGS Table 1B includes an estimate of community (non-public hospital) prescription numbers for the 2005 calendar year, costs (government and patient contribution) for the items with a four digit PBS/RPBS code, together with the defined daily dose (DDD) where assigned. There is no cost information available for items with a five digit Amfac drug code. Table 1 exclude the presentation of information on any item with an estimated community use of less than 110 prescriptions in 2005. The prescription items are arranged by ATC code on generic name, and by form and strength using either the PBS drug code (4 digit) or, for non-PBS items, the Amfac drug code (5 digit). Consult the index (page 255) by generic drug name to obtain the appropriate ATC code. An index by 2nd level of the ATC classification follows: ALIMENTARY TRACT AND METABOLISM PAGE NO A01 STOMATOLOGICAL PREPARATIONS 181 A02 DRUGS FOR ACID RELATED DISORDERS 182 A03 DRUGS FOR FUNCTIONAL GASTROINTESTINAL DISORDERS 185 A04 ANTIEMETICS AND ANTINAUSEANTS 187 A05 BILE AND LIVER THERAPY 188 A06 LAXATIVES 189 A07 ANTIDIARRHOEALS, INTESTINAL 191 ANTIINFLAMMATORY/ANTIINFECTIVE AGENTS A08 ANTIOBESITY PREPARATIONS, EXCLUDING DIET PRODUCTS 193 A09 DIGESTIVES, INCLUDING ENZYMES 194 A10 DRUGS USED IN DIABETES 195 A11 VITAMINS 197 A12 MINERAL SUPPLEMENTS 199 A14 ANABOLIC AGENTS FOR SYSTEMIC USE 200 177 BLOOD AND BLOOD FORMING ORGANS B01 ANTITHROMBOTIC AGENTS 201 B02 ANTIHAEMORRHAGICS 203 B03 -

Some Aspects of the Pharmacology of Oral Anticoagulants

Some aspects of the pharmacology of oral anticoagulants The pharmacology of oral anticoagulants ls discussed with particular rejerence to data of value in the management of therapy. The importance of individual variability in response and drug interaction is stressed. Other effects of these agents which may have clinical utility are noted. William W. Coon, M.D., and Park W. Willis 111, M.D., Ann Arbor, Mich. The Departments of Surgery (Section of General Surgery) and Medicine, University of Michigan Medical School In the twenty-five years sinee the isola dividual struetural features but by a com tion of the hemorrhagie faetor in spoiled bination of several: molecular shape, in sweet clever," the gradually inereasing creased aetivity with 6 membered hetero utilization of oral antieoagulants for the eyclic rings with a substituent in position prevention and therapy of thromboembolie 8 and with a methoxyl rather than a free disease has made them one of the most hydroxl group. Also important is the dernon widely used groups of pharmacologic stration that levorotatory warfarin is seven agents. This review is restrieted to as times more aetive than its enantiomer.F" peets of the pharmaeology of these agents As Hunter and Shepherd'" have pointed whieh may be important to their proper out, the failure to obtain a precise cor clinieal utilization. relation between strueture and antieoagu lant aetivity is "not surprising in view of Relation of structure to function the influence of small struetural changes The oral antieoagulants have been di on sueh variables as solubility, rate of ab vided into four main groups on the basis sorption, ease of distribution, degree of of ehemieal strueture (Fig. -

Oral Anticoagulants (VKA and NOAC) Guidelines for Prescribing, Monitoring and Management

Oral Anticoagulants (VKA and NOAC) Guidelines for prescribing, monitoring and management Contents 1.0 Clinical Guidance 2.0 Vitamin K antagonists (VKA) 2.1 Coumarins and Inandiones 2.2 Indications for VKA and target INR 2.3 Contra-indications 2.4 Initiation 2.5 Dosing 2.6 Monitoring 2.7 Counselling 2.8 Adverse effects 2.9 Discharge 2.10 Reversal of VKA (including high INR) 2.11 Bridging therapy with LMWH or unfractionated heparin 2.12 Surgery 2.13 Discontinuation of therapy Newer oral anticoagulants (NOAC) 3.0 Apixaban 3.1 Indications 3.2 Contra-indications 3.3 Initiation 3.4 Dosing 3.5 Monitoring 3.6 Counselling 3.7 Adverse effects 3.8 Discharge 3.9 Management of adverse effects 3.10 Surgery 3.11 Discontinuation of therapy 4.0 Dabigatran 4.1 Indications 4.2 Contra-indications 4.3 Initiation 4.4 Dosing 4.5 Monitoring 4.6 Counselling 4.7 Adverse effects 4.8 Discharge 4.9 Management of adverse effects 4.10 Surgery 4.11 Discontinuation of therapy Oral Anticoagulants Guideline for prescribing, monitoring and management V3 Author: Alice Foster, Dr Dasgupta Approved by MCGT October 2015 Review by: October 2018 Oral Anticoagulants (VKA and NOAC) Guidelines for prescribing, monitoring and management 5.0 Rivaroxaban 5.1 Indications 5.2 Contra-indications 5.3 Initiation 5.4 Dosing 5.5 Monitoring 5.6 Counselling 5.7 Adverse effects 5.8 Discharge 5.9 Management of adverse effects 5.10 Surgery 5.11 Discontinuation of therapy 6.0 References 7.0 Appendices I. Summary table of all oral anticoagulants II. -

Warfarin, Acenocoumarol, Phenindione

797FM.3.1 ORAL ANTICOAGULANTS – WARFARIN, ACENOCOUMAROL AND PHENINDIONE, WHEN DOSES ARE ADJUSTED BY THE ANTICOAGULATION CLINIC AND PRESCRIBED BY THE GENERAL PRACTITIONER Shared Care Protocol This protocol provides prescribing and monitoring guidance for oral anticoagulant therapy with warfarin, acenocoumarol or phenindione. It should be read in conjunction with the shared care responsibilities, the Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC) available on www.medicines.org.uk/emc and the BNF. BACKGROUND FOR USE This agreement outlines the ways in which the responsibilities for prescribing of oral anticoagulation with warfarin, acenocoumarol or phenindione are shared where the anticoagulation monitoring service recommends doses and the general practitioner (GP) prescribes them. Sharing of care assumes communication between the anticoagulant monitoring service, GP and patient. The intention to share care should be explained to the patient by both the patient’s GP and the healthcare professional initiating treatment. It is important that patients are consulted about treatment and are in agreement with it. Patients treated with oral anticoagulants are under regular follow-up, which provides an opportunity to discuss drug therapy. It is the responsibility of both the anticoagulation monitoring service and the GP to maintain competencies relevant to their roles. The anticoagulation monitoring service is responsible for ongoing audit of the quality assurance components of the service. The doctor who prescribes the medication legally assumes clinical responsibility for the drug and the consequences of its use. SUPPORTING INFORMATION The vitamin K antagonist (VKA) oral anticoagulant of choice is warfarin. A small number of patients are intolerant of warfarin and many of these are able to switch to direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) drugs. -

Examination Questions Chapter I

EXAMINATION QUESTIONS CHAPTER I. GENERAL PHARMACOLOGY AND PRESCRIPTION 1. Essence of pharmacology as a science. Parts and fields of modern pharmacology. 2. The chemical nature of the drug. Factors providing the therapeutic effect of drugs - the pharmacological effect and placebo effect. 3. Sources of drugs. Definition: medicinal agent (medicinal drug, drug), medicinal substance, medicinal form. 4. Stages of development of new medicines and therapeutic dental appointment toothpastes. 5. Types of pharmacotherapy. Deontological problems of pharmacotherapy. 6. Routes of drug administration into the body and their characteristic. 7. Pathological changes in the mucosa of mouth and dental tissues as a result use of medicines. 8. Absorption and distribution of drugs in the body. Bioavailability. Volume of distribution. 9. Transformation of drugs in the body. 10. Routes of elimination of drugs and their characteristics. Clearance. Semi-elimination period. 11. Excretion of drugs through the oral mucosa, the possible consequences. 12. Mechanisms of drug interactions with the receptors. The concept of receptors in pharmacology. 13. Pharmacodynamic drug interactions. Antagonism, synergism, their types. Character of change of drug effect (activity, efficacy), depending on the type of antagonism. 14. Types of action of drugs. 15. Dependence of action of drugs on the chemical structure and physico-chemical properties. 16. The concept of dose. Types doses. Principles and units of drug dosage. 17. The dependence of the action of drugs on the dose, age, gender, individual characteristics of the organism. Idiosyncrasy. 18. Change of action of drugs in their re-introduction. Addictive. Tachyphylaxis. Cumulation. Medicinal dependence. 19. Medical and social aspects of the drug addiction control. -

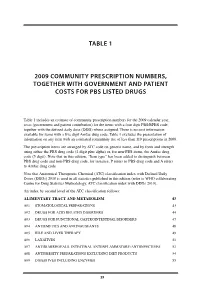

Table 1 2009 Community Prescription Numbers

TABLE 1 2009 COMMUNITY PRESCRIPTION NUMBERS, TOGETHER WITH GOVERNMENT AND PATIENT COSTS FOR PBS LISTED DRUGS Table 1 includes an estimate of community prescription numbers for the 2009 calendar year, costs (government and patient contribution) for the items with a four digit PBS/RPBS code, together with the defined daily dose (DDD) where assigned. There is no cost information available for items with a five digit Amfac drug code. Table 1 excludes the presentation of information on any item with an estimated community use of less than 110 prescriptions in 2009. The prescription items are arranged by ATC code on generic name, and by form and strength using either the PBS drug code (4 digit plus alpha) or, for non-PBS items, the Amfac drug code (5 digit). Note that in this edition, “Item type” has been added to distinguish between PBS drug code and non-PBS drug code, for instance, P refers to PBS drug code and A refers to Amfac drug code. Note that Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification index with Defined Daily Doses (DDDs) 2010 is used in all statistics published in this edition (refer to WHO collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology, ATC classification index with DDDs 2010). An index by second level of the ATC classification follows: ALIMENTARY TRACT AND METABOLISM 43 A01 STOMATOLOGICAL PREPARATIONS 43 A02 DRUGS FOR ACID RELATED DISORDERS 44 A03 DRUGS FOR FUNCTIONAL GASTROINTESTINAL DISORDERS 47 A04 ANTIEMETICS AND ANTINAUSEANTS 48 A05 BILE AND LIVER THERAPY 49 A06 LAXATIVES 51 A07 ANTIDIARRHOEALS, INTESTINAL ANTIINFLAMMATORY/ANTIINFECTIVES -

Guidelines for the Prescribing and Monitoring of Oral Anticoagulant

Guidelines for the Prescribing and Monitoring of Oral Anticoagulant Therapy including direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs), Low Molecular Weight Heparins (LMWH), Unfractionated Heparin and Fondaparinux Sodium on Inpatient Units GUIDELINES NUMBER V5 RATIFYING COMMITTEE Drugs and Therapeutics Group DATE FIRST RATIFIED October 25th 2010 NEXT REVIEW DATE April 2022 ORIGINAL AUTHORS Jed Hewitt – Chief Pharmacist, Governance & Professional Practice. Trudie Morgan – Lead Clinical Pharmacist Miguel Gomez – Lead Clinical Pharmacist LATEST REVIEW BY Trudie Morgan EXECUTIVE SPONSOR Chief Medical Officer Version 1 – July 2008 Amended – November 2009 Version 2 – October 2010 Version 3 – January 2014 Version 4 – October 2015 Version 5 - April 2019 Summary: This guidance aims to assist staff in: The safe prescribing, administration and monitoring of oral and sub-cutaneous anticoagulant therapy for the treatment and prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism. Note: Warfarin is by far the most commonly used oral anticoagulant. However, the use of direct oral anticoagulants (eg, rivaroxaban) is gradually increasing. These directly act on clotting factors and do not require routine monitoring of INR value. If you require this document in an alternative format, i.e. easy read, large text, audio or Braille please contact the pharmacy team on 01243 623349. 1 Contents: Page Part 1A - Guidelines for the prescribing, administration and monitoring of 3 vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant therapy on inpatient units (e.g. warfarin) Part 1B - Guidelines for the prescribing, administration and monitoring of 5 direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) therapy on inpatient units (e.g. ribaroxaban) Part 2 - Guidelines for the prescribing, administration and monitoring of 8 low molecule weight heparins (LMWHs) on inpatient units Part 3 - Guidelines for the prescribing, administration and monitoring of 9 unfractionated heparins and fondaparinux sodium on inpatient units Part 4 - Advice on what to do if patients on anticoagulants need dental 10 treatment.