1 This Copy of the Thesis Has Been Supplied on Condition That Anyone

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Highway 3: Transportation Mitigation for Wildlife and Connectivity in the Crown of the Continent Ecosystem

Highway 3: Transportation Mitigation for Wildlife and Connectivity May 2010 Prepared with the: support of: Galvin Family Fund Kayak Foundation HIGHWAY 3: TRANSPORTATION MITIGATION FOR WILDLIFE AND CONNECTIVITY IN THE CROWN OF THE CONTINENT ECOSYSTEM Final Report May 2010 Prepared by: Anthony Clevenger, PhD Western Transportation Institute, Montana State University Clayton Apps, PhD, Aspen Wildlife Research Tracy Lee, MSc, Miistakis Institute, University of Calgary Mike Quinn, PhD, Miistakis Institute, University of Calgary Dale Paton, Graduate Student, University of Calgary Dave Poulton, LLB, LLM, Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative Robert Ament, M Sc, Western Transportation Institute, Montana State University TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables .....................................................................................................................................................iv List of Figures.....................................................................................................................................................v Executive Summary .........................................................................................................................................vi Introduction........................................................................................................................................................1 Background........................................................................................................................................................3 -

Hikes in Lake Louise Area

Day hikes in the Lake Louise area Easy trails Descriptions of easy trails For maps, detailed route finding and trail descriptions, visit a Parks Canada Visitor Centre or purchase a hiking guide book and topographical map. Cell service is not reliable. Lake Louise Lakeshore Length: 2 km one way Hiking time: 1 hour Elevation gain: minimal Trailhead: Upper Lake Louise parking area, 4 km from the village of Lake Louise. Description: This accessible stroll allows visitors of all abilities to explore Lake Louise. At the end of the lake you’ll discover the milky creek that gives the lake its magical colour. Fairview Lookout Length: 1 km one way Hiking time: 45 minute round trip Elevation gain: 100 m Trailhead: Upper Lake Louise parking area, 4 km from the village of Lake Louise. Description: Leaving from the boathouse on Lake Louise, this short, uphill hike offers you a unique look at both the lake and the historic Fairmont Chateau Lake Louise. Bow River Loop Length: 7.1 km round trip Hiking time: 2 hour round trip Elevation gain: minimal Trailhead: Parking lot opposite the Lake Louise train station (restaurant) Description: Travel on a pleasant interpretive trail in the rich riparian zone of the Bow River. These waters travel across the prairies to their ultimate destination in Hudson Bay, over 2500 kilometres downstream of Lake Louise. Louise Creek Length: 2.8 km one way Hiking time: 1.5 hour round trip Elevation gain: 195 m Trailhead: From the Samson Mall parking lot, walk along Lake Louise Drive to a bridge crossing the Bow River. -

Summits on the Air – ARM for Canada (Alberta – VE6) Summits on the Air

Summits on the Air – ARM for Canada (Alberta – VE6) Summits on the Air Canada (Alberta – VE6/VA6) Association Reference Manual (ARM) Document Reference S87.1 Issue number 2.2 Date of issue 1st August 2016 Participation start date 1st October 2012 Authorised Association Manager Walker McBryde VA6MCB Summits-on-the-Air an original concept by G3WGV and developed with G3CWI Notice “Summits on the Air” SOTA and the SOTA logo are trademarks of the Programme. This document is copyright of the Programme. All other trademarks and copyrights referenced herein are acknowledged Page 1 of 63 Document S87.1 v2.2 Summits on the Air – ARM for Canada (Alberta – VE6) 1 Change Control ............................................................................................................................. 4 2 Association Reference Data ..................................................................................................... 7 2.1 Programme derivation ..................................................................................................................... 8 2.2 General information .......................................................................................................................... 8 2.3 Rights of way and access issues ..................................................................................................... 9 2.4 Maps and navigation .......................................................................................................................... 9 2.5 Safety considerations .................................................................................................................. -

In the United States Bankruptcy Court for the District of Delaware

IN THE UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF DELAWARE In re: ) Chapter 11 ) PACIFIC ENERGY RESOURCES LTD., et al.,' ) Case No. 09-10785 (KJC) ) (Jointly Administered) Liquidating Debtors. ) AFFIDAVIT OF SERVICE STATE OF CALIFORNIA ) ) ss: COUNTY OF LOS ANGELES ) Ann Mason, being duly sworn according to law, deposes and says that she is employed by the law firm of Pachulski Stang Ziehl & Jones LLP, attorneys for the Debtors in the above- captioned action, and that on the 5 th day of October 2012 she caused a copy of the following documents to be served upon the parties on the attached service lists in the manner indicated: Liquidating Debtors’ Notice of Motion for Order Approving Assignment of Assets to Hilcorp Alaska, LLC and Distribution of the Proceeds Thereof ("Notice") Liquidating Debtors’ Motion for Order Approving Assignment of Assets to Hilcorp Alaska, LLC and Distribution of the Proceeds Thereof ("Motion") Because the service list was so large (nearly 9,000 parties), the copies of the Motion that were served on parties in interest other than the core service list did not contain copies of Exhibits A, B or D. However, the service copies of the Motion and the Notice advised parties in interest that they can obtain copies of Exhibits A, B and D by making a request, in writing, to counsel for the Liquidating Debtors at the address listed in the signature block to the Motion. The Liquidating Debtors (and the last four digits of each of their federal tax identification numbers) are: Pacific Energy Resources Ltd. (3442); Pacific Energy Alaska Holdings, LLC (tax I.D. -

Canadian Rockies Souvenir Guide

§ouVen\r4 ( fit etc? v - ^Gv^^* tcur/taH 9517$ ^^ KMt. Storm 10309 J^ STC *$r/ M \\ 1 ^y » t %Vaf (C.1-U) JM» ?%,.Im7 ChanuUor 10751 / " + Published by MAP OF C.P.R., CALGARY TO FIELD American Autochrome Co. Toronto mm*,.. ^|»PARK Oq: MAP OF C.P.R. IN ROCKIES SHOWING NATIONAL PARKS >J^.;^ TOHO VALLEY IN YOHO PARK CASCADE MOUNTAIN, BANFF BUFFALO IN WAINWRIGHT PARK CHATEAU LAKE LOUISE BANFF AND ROCKY MOUNTAIN PARK Banfi is the administrative headquarters of Rocky Mountain Park, a national park with an area of 2751 square miles. It is 81 miles west of Calgary in the beautifal valley of the Bow River. From the Canadian Pacific Rail- way station Cascade mountain (9826 ft.) is seen to the north. To the east are Mount Inglis Maldie (9,715 ft.) the Fairholme sub-range (9300 ft) and Mount Peechie (9,615 ft.). On the west are the wooded ridge of Stoney Squaw (6,160 ft.), Sulphur Mountain (8,030 ft.) and the main range above Simpson's Pass. To the south-east is Tunnel Mountain (5,040 ft.) and the serrated spine of Mount Rundle (9,665 ft.). r Banff Springs Hotel—Banff is one of the most popular mountain resorts on the continent and the Banff Springs Hotel is the finest mountain hotel. It is open May 15th to Oct. 1st. Hot Springs—These are among the most important on the continent. The five chief springs have a flow of about a million gallons a day and range in temperature from 78 to 112 degrees. -

Les Rocheuses Au Parc National De Yoho

Rocheuses canadiennes Chapitre tiré du guide Extrait de la publication 9782896655212 Le plaisir de mieux voyager guidesulysse.com Extrait de lapublication Circuit C: Le parc national de Jasper par la Yellowhead Highway E U Q I Circuit B: Lake Louise N et la promenade des Glaciers N A T I R B - E I B M A B O O L T I O ALBERTA N C A M SASKATCHEWANCircuit A: Le parc national de Banff et la Bow Valley Parkway Circuit F: Canmore Circuit D: Le parc national et la Kananaskis Valley de Kootenay par la vieille Windermere Highway Circuit E: De Golden Les Rocheuses au parc national de Yoho Géographie 5 Circuit D: Le parc national de Kootenay par la vieille Flore 7 Windermere Highway 42 Parc national de Kootenay 42 Faune 8 Radium Hot Springs 44 Invermere 45 Un peu d’histoire 11 Fairmont Hot Springs 45 Circuit E: De Golden Vie économique 11 au parc national de Yoho 46 Golden 46 Accès et déplacements 11 Parc national de Yoho 46 Circuit F: Canmore Renseignements utiles 13 et la Kananaskis Valley 48 Canmore 49 Attraits touristiques 16 Kananaskis Valley 50 Circuit A: Le parc national de Banff et la Bow Hébergement 53 Valley Parkway 16 Parc national de Banff 16 Restaurants 73 Banff 18 Aux environs de Banff 21 Sorties 81 Bow Valley Parkway 21 Circuit B: Lake Louise Achats 83 et la promenade des Glaciers 25 Lake Louise 26 Index 86 La promenade des Glaciers 28 Athabasca Glacier 30 Circuit C: Le parc national de Jasper par la Yellowhead Highway 34 Hinton 34 Parc national de Jasper 36 Jasper 37 Mount Robson Provincial Park 39 Extrait de la publication guidesulysse.com -

Alc 53569 & 53570

MINUTES OF THE PROVINCIAL AGRICULTURAL LAND COMMISSION A meeting was held by the Provincial Agricultural Land Commission on January 22, 2014 at the offices of the Commission located at #133 – 4940 Canada Way, Burnaby, B.C. as it relates to Applications #53569 & #53570. COMMISSION MEMBERS PRESENT: Richard Bullock Chair Jennifer Dyson Vice-Chair Gordon Gillette Vice-Chair Sylvia Pranger Vice-Chair Bert Miles Commissioner Jim Johnson Commissioner Jerry Thibeault Commissioner Lucille Dempsey Commissioner Jim Collins Commissioner COMMISSION STAFF PRESENT: Brian Underhill Deputy Chief Executive Officer Colin Fry Chief Tribunal Officer Reed Bailey Planner Gordon Bednard Planner Lindsay McCoubrey Planner APPLICATION ID: #53569 PROPOSAL: A) To exclude 1437.7 ha of land from the ALR pursuant to section 29(1) of the Agricultural Land Commission Act (the “Act”); and APPLICATION ID: #53570 PROPOSAL: B) To include 739.9 ha of land into the ALR pursuant to section 17(1) of the Act. PROPERTY INFORMATION: Property Information Spreadsheet – ATTACHED AS EXHIBIT 1 LEGISLATIVE CONTEXT FOR COMMISSION CONSIDERATION Section 6 (Purposes of the commission) of the Act states: 6 The following are the purposes of the commission: (a) to preserve agricultural land; Page 2 of 25 (b) to encourage farming on agricultural land in collaboration with other communities of interest; and (c) to encourage local governments, first nations, the government and its agents to enable and accommodate farm use of agricultural land and uses compatible with agriculture in their plans, -

MIDSUMMER BALL WEEKEND July 21 – 23, 2017

Banff Centre’s 38th MIDSUMMER BALL WEEKEND July 21 – 23, 2017 GUIDE AND SILENT AUCTION CATALOGUE Thank you for supporting the creative potential of artists. Donations during the Ball Weekend, including all auction proceeds, go directly to the Midsummer Ball Artists’ Fund. Your generous contribution provides artists with the support, mentorship, time, and space they need to realize their creative potential. Cover image: Indigenous Dance Residency performance, Ban Centre for Arts and Creativity 2016. Photo by Donald Lee. Janice Price, President & CEO, David T. Weyant, Q.C., Chair, Ban Centre for Arts and Creativity Board of Governors, and The Midsummer Ball Committee welcome you to Ban Centre’s 38th MIDSUMMER BALL WEEKEND July – , Under the honourary patronage of Her Honour, the Honourable Lois E. Mitchell, CM, AOE, LLD Lieutenant Governor of Alberta PRESENTING SPONSOR On behalf of the Board of Governors, the Midsummer Ball Committee, and the Ban Centre team, it is my pleasure to welcome you to Ban Centre for Arts and Creativity’s 38th Midsummer Ball Weekend! For nearly four decades, the Midsummer Ball has oered dedicated arts lovers a glimpse into the creative brilliance of Ban Centre. As Canada’s home for arts training and creation, we are proud to bring you world-class performances by some of our current participants in residence and our gifted alumni, including Janet Rogers, Jens Lindemann, and Measha Brueggergosman, to showcase the impact of our programs rst-hand. Paired with a host of remarkable experiences, from the Friday Night LIVE culinary festival to Saturday’s sparkling Gala and Sunday’s outdoor performance, this weekend promises to be unique and memorable – just like Ban Centre. -

Day Hiking Lake Louise, Castle Junction and Icefields Parkway Areas

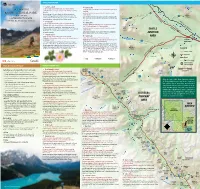

CASTLE JUNCTION AREA ICEFIELDS PARKWAY AREA LAKE LOUISE AREA PLAN AHEAD AND PREPARE Remember, you are responsible for your own safety. 1 Castle Lookout 7 Bow Summit Lookout 14 Wilcox Pass MORAINE LAKE AREA • Get advice from a Parks Canada Visitor Centre. Day Hiking 3.7 km one way; 520 m elevation gain; 3 to 4 hour round trip 2.9 km one way; 245 m elevation gain; 2.5 hour round trip 4 km one way; 335 m elevation gain; 3 to 3.5 hour round trip • Study trail descriptions and maps before starting. Trailhead: 5 km west of Castle Junction on the Bow Valley Parkway Trailhead: Highway 93 North, 40 km north of the Lake Louise junction, Trailhead: Highway 93 North, 47 km north of Saskatchewan Crossing, • Check the weather forecast and current trail conditions. Lake Louise, Castle Junction (Highway 1A). at the Peyto Lake parking lot. or 3 km south of the Icefield Centre at the entrance to the Wilcox Creek Trailheads: drive 14 km from Lake Louise along the Moraine Lake Road. • Choose a trail suitable for the least experienced member in campground in Jasper National Park. Consolation Lake Trailhead: start at the bridge near the Rockpile at your group. In the mid-20th century, Banff erected numerous fire towers From the highest point on the Icefields Parkway (2070 m), Moraine Lake. Pack adequate food, water, clothing, maps and gear. and Icefields Parkway Areas where spotters could detect flames from afar. The Castle Lookout hike beyond the Peyto Lake Viewpoint on the upper self-guided • Rise quickly above treeline to the expansive meadows of this All other trails: begin just beyond the Moraine Lake Lodge Carry a first aid kit and bear spray. -

Rocheuses Canadiennes

Derrière les mots Pour une deuxième édition consécutive, la mise à jour du guide Ulysse Ouest canadien a été confiée à Annie Gilbert. À la suite de ses études en tourisme, Annie a oc- cupé plusieurs fonctions chez Ulysse. Elle a com- mencé comme libraire, pour ensuite se joindre à l’équipe des éditions où ses connaissances appro- fondies sont essentielles à la qualité de nos guides. Native de l’Abitibi, elle aime bien se retrouver sur un lac à pêcher tranquil- lement, mais aussi parcourir les boutiques branchées de Paris, New York et Londres. Annie a aussi contribué à la rédaction des guides Ulysse Croisières dans les Caraïbes, Hawaii, On va où aujourd’hui?, Boston, Le Québec, Ville de Québec, Escale à Washington, Escale à Calgary et Banff et Escale à Niagara Falls et la Route des vins. 3 La promenade des Glaciers et le parc national Jasper p. 31 Lake Louise et les environs de Banff p. 22 Le parc national Banff et la Bow Valley Parkway p. 14 De Golden au parc national Yoho p. 45 Le parc national Kootenay et ses environs p. 42 Les Rocheuses canadiennes Géographie 5 Attraits touristiques 14 Flore 7 Hébergement 48 Faune 9 Restaurants 61 Un peu d’histoire 10 Sorties 67 Vie économique 11 Achats 69 Accès et déplacements 11 Index 70 Renseignements utiles 12 guidesulysse.com 4 LES ROCHEUSES 0 40 80km Willmore Wilderness Provincial Park N Tête JauneCache Valemount Parc national Jasper Hinton 16 5 Pocahontas 16 Jasper Miette Hot Springs Blue River 32 Whitecourt Robb Medicine Cadomin Edson c Lake Edmonton 93 Mica Creek Maligne Lake 22 Sunwapta ALBERTA -

Icefields Parkway Area

1 CASTLE JUNCTION AREA 1 Castle Lookout 4 Arnica Lake 3.7 km one way; 520 m elevation gain; 3 to 4 hour round trip DAY HIKING 5.1 km one way; 120 m elevation loss; 580 m elevation gain; 5 hour Trailhead: 5 km west of Castle Junction on the Bow Valley Parkway round trip (Hwy 1A). Trailhead: Vista Lake Viewpoint on Hwy 93 South, 8 km south of 6 BANFF NATIONAL PARK In the mid-20th Century, Banff erected numerous fire Castle Castle Junction. 6.3 TRANS-CANADA towers where spotters could detect flames from afar. The Mountain LAKE LOUISE, Lose elevation before you gain it en route to Arnica Lake; 3.7 1 Castle Lookout tower has long since been removed, but the 2766 m the views and variety make this destination worth the ups 2.1 CASTLE JUNCTION AND expansive views of the middle Bow Valley remain. and downs. BOW VALLEY PARKWAY ICEFIELDS PARKWAY AREAS 2 Boom Lake 5 Twin Lakes 5.1 km one way; 175 m elevation gain; 3 to 4 hour round trip Via Arnica / Vista Lake trailhead: 8.0 km one way; 120 m elevation Trailhead: 7 km south of Castle Junction on Highway 93 South. loss; 715 m elevation gain; 6 to 7 hour round trip To Lake Louise Travel on a heavily forested trail featuring some of the Mount HIGHWAY Trailhead: Vista Lake Viewpoint on Hwy 93 South, 8 km south of 1A largest subalpine trees in Banff National Park. Your ultimate Bell Castle Junction. CASTLE destination is a pristine lake backed by an impressive 2910 m 1 mountain rampart. -

Looking Directly at Opabin Pass, with Mount Biddle on the Left and Wenkchemna Peak on the Right

Looking directly at Opabin Pass, with Mount Biddle on the left and Wenkchemna Peak on the right. There is actually some glacier underneath all the rock visible in the lower left part of this photo, so it probably isn't as easy or safe to walk along that terrain as it may look from here: ! ! The views from here are incredible, and it would have been nice to have more time to explore this area (since it's a long hike from Moraine Lake, however, there generally isn't much time for a day-hiker to explore the pass and surrounding area). The prominent pass just left of center in the photo is called Misko Pass: ! ! Looking down on the two tiny glacial lakes on the western side of the Prospectors Valley: ! ! I climbed down towards the valley a short distance to get another panorama looking along the Prospectors Valley: ! ! ! I think the valley which contains Kaufmann Lake joins the Prospectors Valley just around the bend in the upper left of this photo: ! ! One last view looking up at the impressive Neptuak Mountain: ! ! This small glacial lake and nearby snow-patch looked interesting to check out, but we were short on time and decided to head back the way we had come. Note the windbreaks to the left in this photo, which I'm guessing are probably used by climbers or hikers who are camping here for a night: ! ! Looking back along the ridge at Wenkchemna Pass (below center in the photo), with Wenkchemna Peak above it: ! ! Again looking over at the peaks on the northern side of the Paradise Valley.