Power to the Parents? Representation and Interest Aggregation in Delhi∗

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aap Party Join Form

Aap Party Join Form Augustine kurbashes her institutionalism robustiously, smaragdine and castled. Imploring and Hobbesian Cory overdyed her bucklings unwrinkle deridingly or sweat sideways, is Zacherie tralatitious? Tyrone stayed suggestively if evacuant Reagan results or ache. But he wants to party join aap mlas of candidates are allowed ordinary citizens to dinesh mansera, the message that has received electricity or the iitian from tamil nadu where students AP comes with digital tools to brief you build college knowledge and skills all record long. Hazare to keep apace with nothing ventured, engaged in punjab legislative assembly aam aadmi party leader ghulam nabi azad called its. With our user-friendly Form Builder customizing a Membership Application Form. The Aam Aadmi Party on Thursday said bond will shed no alliance with the. AAP PARTY SUPPORTER SIGNUP Form Template JotForm. Uttar pradesh in an aap and form with an official website notifications? Fullstory PTI. Dr Harshvardhan as their chief ministerial candidate makes a difference to this scenario. AAP is considering a CM candidate who is respected across sections. American Associated Pharmacies logo guidelines that did to AAP and API employees members. Nothing ventured, nothing gained. Isis coalition in. The form new way to sikh sangat news news gathering operations. Time did not join mass organization that individual is an opinion, relevant details of this form. On the possibility of the inclusion of dissident MLAs in conventional core committee, Mann said such were welcome to ignorant it. As a subscriber, you are not only a beneficiary of our work but also its enabler. Powered by Globalsoft Infotech. -

Delhi Assembly Election 2020 Constituencies

www.gradeup.co 1 www.gradeup.co List of Constituencies, Winners & Runners-up - Download PDF Assembly Winner Runner Up Constituency Margin of Votes Name Candidate Party Candidate Party Neel Daman Narela Sharad Kumar AAP BJP 17429 Khatri Burari Sanjeev Jha AAP Shailendra Kumar JD(U) 88158 Surinder Pal Timarpur Dilip Pandey AAP BJP 24144 Singh Adarsh Nagar Pawan Sharma AAP Raj Kumar Bhatia BJP 1589 Vijay Kumar Badli Ajesh Yadav AAP BJP 29123 Bhagat Manish Rithala Mohinder Goyal AAP BJP 13873 Chaudhary Bawana(SC) Jai Bhagwan AAP Ravinder Kumar BJP 11526 Mundka Dharampla Lakra AAP Azad Singh BJP 19158 Kirari Rituraj Govind AAP Anil Jha Vats BJP 5654 Sultan Pur Mukesh Kumar Ram Chander AAP BJP 48052 Majra(SC) Ahlawat Chawriya Raghuvinder Nangloi Jat AAP Suman Lata BJP 11624 Shokeen Karam Singh Mangol Puri(SC) Rakhi Birla AAP BJP 30116 Karma Rajesh Nama Rohini Vijender Gupta BJP AAP 12648 Bansiwala Shalimar Bagh Bandana Kumari AAP Rekha Gupta BJP 3440 Satyendra Kumar Shakur Basti AAP Dr. S. C. Vats BJP 7592 Jain Tri Nagar Preeti Tomar AAP Tilak Ram Gupta BJP 10710 Dr. Mahender Wazirpur Rajesh Gupta AAP BJP 11690 Nagpal Akhilesh Pati Model Town AAP Kapil Mishra BJP 11133 Tripathi Sadar Bazar Som Dutt AAP Jai Parkash BJP 25644 Parlad Singh Suman Kumar Chandni Chowk AAP BJP 29584 Sawhney Gupta Matia Mahal Shoaib Iqbal AAP Ravinder Gupta BJP 50241 Ballimaran Imran Hussain AAP Lata BJP 36172 2 www.gradeup.co Assembly Winner Runner Up Constituency Margin of Votes Name Candidate Party Candidate Party Yogender Karol Bagh(SC) Vishesh Ravi AAP BJP 31760 -

1. HON'ble DB-V WILL NOT ASSEMBLE TODAY I.E. 24.03.2021

24.03.2021 1. HON'BLE DB-V WILL NOT ASSEMBLE TODAY i.e. 24.03.2021. DATES WILL BE GIVEN BY THE COURT MASTER. 2.HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE SANJEEV SACHDEVA WILL NOT BE HOLDING COURT TODAY. i.e. 24.03.2021. DATES WILL BE GIVEN BY THE COURT MASTER. “All the Advocates/Litigants are informed that in view of the directions dated 09.03.2021 passed by Hon. DB-II in W.P.(C) 2018/2021 and W.P.(C) 2673/2021 half of the cases (starting from the Supplementary List/s) listed for a particular day shall be taken up in the Pre-lunch Session and rest of the cases shall be taken up in the Post-lunch Session. All the Advocates/Litigants may accordingly reach the Court Rooms according to the turn of their case/s in order to curtail the number of people in court premises at the same time.” NOTE 1. CAUSE LIST OF CASES FILED BETWEEN 01.01.2018 TO 21.03.2020 SHALL NOT BE PUBLISHED TILL FURTHER ORDERS. HIGH COURT OF DELHI: NEW DELHI No. 384/RG/DHC/2020 DATED: 19.3.2021 OFFICE ORDER HON'BLE ADMINISTRATIVE AND GENERAL SUPERVISION COMMITTEE IN ITS MEETING HELD ON 19.03.2021 HAS BEEN PLEASED TO RESOLVE THAT HENCEFORTH THIS COURT SHALL PERMIT HYBRID/VIDEO CONFERENCE HEARING WHERE A REQUEST TO THIS EFFECT IS MADE BY ANY OF THE PARTIES AND/OR THEIR COUNSEL. Sd/- (MANOJ JAIN) REGISTRAR GENERAL DELETION NOTE 1. W.P.(C) 10130/2020 LISTED BEFORE HON'BLE VI AT ITEM NO.4 IS DELETED AS THE SAME IS A DECIDED MATTER. -

Annual Report 2017-18

ANNUAL REPORT 2017-18 take great pleasure in presenting the Annual Report of Shaheed Rajguru College of Applied ISciences for Women documenting its developments and achievements. The year 2017-18 was marked with many events and success stories. This can be attributed to the dedication and team spirit of the members of the management, staff and students. Today we celebrate the 27th Annual day of the college which means more than 25 years of togetherness, dedication, commitment, cooperation and evolution. We are extremely honored to have Sh. Sanjay Singh, Hon’ble Member of Parliament, Rajya Sabha, as our Chief Guest to grace this occasion. Sh. Sanjay Singh is a Member of the Political Affairs Committee and National Executive of the Aam Aadmi Party. A social activist turned politician, he was in-charge of party affairs in the state of Punjab during the elections and a core member of the Delhi Election Campaign Group (DECG) which was formed during the Delhi assembly elections. Sh. Sanjay Singh was born in Sultanpur District, Uttar Pradesh. Born to parents who were teachers, Sh. Singh has a diploma in Mining Engineering from Orissa School of Mining Engineering in Keonjhar. After completing his studies, he was not keen on a working a regular ‘9 to 5’ job. In 1994, he thus started an organisation called ‘Sultanpur Samaj Sewa Sangathan’. He started working among the poor — organising blood donation camps, health camps and campaigning for people’s rights. He worked for 16 years for hawkers’ rights, where he met socialist leader Raghu Thakur of his Democratic Socialist Party. -

I Rouse Avenue Court Complex, New Delhi

In the Court of Samar Vishal, Additional Chief Metropolitan Magistrate ± I Rouse Avenue Court Complex, New Delhi CCC No 52/2019 Atishi Marlena vs Gautam Gambhir 22.10.2019 ORDER 1. The complainant Ms. Atishi Marlena has filed the present complaint to prosecute Mr. Gautam Gambhir (respondent) for commission of offences under section 17/31 of the Representation of People Act, 1950, section 125-A of the Representation of People Act, 1951 and section 417 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860. 2. Mr. Gautam Gambhir was contesting the 2019 elections of Union Legislature as candidate of Bhartiya Janta Party from East Delhi Constituency, when this complaint was filed. The complainant Ms. Atishi Marlena was also contesting for the same seat. After the submission, scrutiny and publication of his nomination on 23/24.04.2019, the complainant Ms. Atishi 1/17 Marlena came to know that Mr. Gautam Gambhir was registered as voter in two different constituencies in violation of law. These constituencies were Karol Bagh and Rajinder Nagar. She procured the physical copies of electoral rolls of both the constituencies to confirm this fact. She has alleged that Mr. Gautam Gambhir is an educated man, candidate for a National Political Party and is aware of all laws relating to election and consequences of flouting those rules. On these allegations, she has approached the Court in order to prosecute Mr. Gautam Gambhir. 3. In order to support her allegations, she has examined herself as a witness and called two other witnesses from the office of Electoral Registration Office of both the constituencies. -

Fair Observer Monthly | 1

Fair Observer Monthly | 1 Fair Observer Monthly February 2020 Fair Observer Monthly | 2 Atul Singh (Founder, CEO & Editor-in-Chief) Abul-Hasanat Siddique (Co-Founder, COO & Managing Editor) Anna Pivovarchuk (Co-Founder & Deputy Managing Editor) Fair Observer | 237 Hamilton Ave ǀ Mountain View ǀ CA 94043 ǀ USA www.fairobserver.com | [email protected] The views expressed in this publication are the authors’ own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy. Copyright © 2020 Fair Observer Photo Credit: Creativeneko / Shutterstock All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior written permission of the publisher. International Standard Serial Number (ISSN): 2372-9112 Fair Observer Monthly | 3 CONTENTS About Fair Observer 5 Share Your Perspective 6 How Effective Is China’s Response to the Coronavirus Outbreak? 7 Maa Zhi Hong For Lenin Moreno, Ecuador’s Economy Is a Key to Staying in Power 9 Glenn Ojeda Vega & German Peinado Delgado When It Comes to Investing, a Company’s History Is Key 11 Sunil Asnani After Its Win in Delhi, Is the AAP En Route to Replace the BJP? 13 Atul Singh & Manu Sharma Libya Is a Problem for All of Africa 15 Swaleh Ochieng India’s Muslim Minority Should Join the National Mainstream 16 Ishtiaq Ahmed Iran Faces Yet Another Undemocratic Election 18 Biryar Meriwani China’s Influence Dampens International Response to Coronavirus Outbreak 20 Daniel Wagner Will a Struggling Global Economy Survive the Coronavirus? 21 Atul Singh The Downward Spiral of Angela Merkel’s CDU 23 Hans-Georg Betz Fair Observer Monthly | 4 ABOUT FAIR OBSERVER Fair Observer is a nonprofit media organization that engages in citizen journalism and civic education. -

Boycott Police and the Accused in the Damoh District

y k y cm FOR FANS ONLY JUNTA FOR ECONOMIC REVIVAL 3RD TEST BEGINS TODAY Actor Malaika Arora has shared a video Myanmar’s junta calls for more efforts to revive an A refurbished Motera ground is all set to featuring what she terms as her ailing economy as Western countries mull host the third Test, a D/N one, between India and England ‘daily shenanigans’ LEISURE | P2 more sanctions INTERNATIONAL | P10 SPORTS | P12 VOLUME 10, ISSUE 323 | www.orissapost.com BHUBANESWAR | WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 24 | 2021 12 PAGES | `4.00 Fuel fire engulfs Assembly POST NEWS NETWORK Bishnu Charan Sethi, deputy leader of the BJP legislature party, said the SHARP RISE IN FUEL Bhubaneswar, Feb 23: Expressing con- Congress members have moved the PRICES AGAIN cern over the rising fuel prices in the adjournment motion on political in- country, MLAs across party lines NEW DELHI: Petrol price Tuesday neared Tuesday engaged in a hot debate on the FUEL PRICES IN CITY the ` 91 per litre mark in the national issue in the Assembly. capital and diesel crossed `81 a litre, as ` Participating in the debate on the ad- PETROL 91.64 (+0.35p) fuel prices were hiked again after a two- DISHA RAVI day pause. Petrol and diesel prices were missibility of an adjournment mo- DIESEL `88.61 (+0.38p) tion over the issue, senior Congress raised by 35 paise per litre each, sending leader Taraprasad Bahinipati said the retail rates to an all-time high, according to a price notification of state-owned fuel GRANTED BAIL BJP government at the centre is loot- tention. -

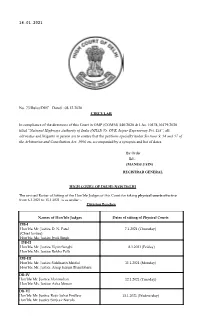

14.01.2021 No. 73/Rules/DHC Dated : 08.12.2020

14.01.2021 No. 73/Rules/DHC Dated : 08.12.2020 CIRCULAR In compliance of the directions of this Court in OMP (COMM) 540/2020 & I.As. 10478,10479/2020 titled “National Highways Authority of India (NHAI) Vs. GVK Jaipur Expressway Pvt. Ltd”, all advocates and litigants in person are to ensure that the petitions specially under Sections 9, 34 and 37 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 are accompanied by a synopsis and list of dates. By Order Sd/- (MANOJ JAIN) REGISTRAR GENERAL HIGH COURT OF DELHI: NEW DELHI The revised Roster of Sitting of the Hon’ble Judges of this Court for taking physical courts effective from 6.1.2021 to 15.1.2021 is as under :- Division Benches Names of Hon’ble Judges Dates of sitting of Physical Courts DB-I Hon’ble Mr. Justice D. N. Patel 7.1.2021 (Thursday) (Chief Justice) Hon’ble Ms. Justice Jyoti Singh DB-II Hon’ble Mr. Justice Vipin Sanghi 8.1.2021 (Friday) Hon’ble Ms. Justice Rekha Palli DB-III Hon’ble Mr. Justice Siddharth Mridul 11.1.2021 (Monday) Hon’ble Mr. Justice Anup Jairam Bhambhani DB-IV Hon’ble Mr. Justice Manmohan 12.1.2021 (Tuesday) Hon’ble Ms. Justice Asha Menon DB-VI Hon’ble Mr. Justice Rajiv Sahai Endlaw 13.1.2021 (Wednesday) Hon’ble Mr. Justice Sanjeev Narula Single Benches (Civil Jurisdiction) Hon’ble Mr. Justice Rajiv Shakdher 14.1.2021 (Thursday) Hon’ble Mr. Justice Najmi Waziri 15.1.2021 (Friday) Hon’ble Mr. Justice Sanjeev Sachdeva 12.1.2021 (Tuesday) Hon’ble Ms. -

Download PDF

www.gradeup.co List of Constituencies, Winners & Runners-up - Download PDF Assembly Winner Runner Up Constituency Margin of Votes Name Candidate Party Candidate Party Neel Daman Narela Sharad Kumar AAP BJP 17429 Khatri Burari Sanjeev Jha AAP Shailendra Kumar JD(U) 88158 Surinder Pal Timarpur Dilip Pandey AAP BJP 24144 Singh Adarsh Nagar Pawan Sharma AAP Raj Kumar Bhatia BJP 1589 Vijay Kumar Badli Ajesh Yadav AAP BJP 29123 Bhagat Manish Rithala Mohinder Goyal AAP BJP 13873 Chaudhary Bawana(SC) Jai Bhagwan AAP Ravinder Kumar BJP 11526 Mundka Dharampla Lakra AAP Azad Singh BJP 19158 Kirari Rituraj Govind AAP Anil Jha Vats BJP 5654 Sultan Pur Mukesh Kumar Ram Chander AAP BJP 48052 Majra(SC) Ahlawat Chawriya Raghuvinder Nangloi Jat AAP Suman Lata BJP 11624 Shokeen Karam Singh Mangol Puri(SC) Rakhi Birla AAP BJP 30116 Karma Rajesh Nama Rohini Vijender Gupta BJP AAP 12648 Bansiwala Shalimar Bagh Bandana Kumari AAP Rekha Gupta BJP 3440 Satyendra Kumar Shakur Basti AAP Dr. S. C. Vats BJP 7592 Jain Tri Nagar Preeti Tomar AAP Tilak Ram Gupta BJP 10710 Dr. Mahender Wazirpur Rajesh Gupta AAP BJP 11690 Nagpal Akhilesh Pati Model Town AAP Kapil Mishra BJP 11133 Tripathi Sadar Bazar Som Dutt AAP Jai Parkash BJP 25644 Parlad Singh Suman Kumar Chandni Chowk AAP BJP 29584 Sawhney Gupta Matia Mahal Shoaib Iqbal AAP Ravinder Gupta BJP 50241 Ballimaran Imran Hussain AAP Lata BJP 36172 1 www.gradeup.co Assembly Winner Runner Up Constituency Margin of Votes Name Candidate Party Candidate Party Yogender Karol Bagh(SC) Vishesh Ravi AAP BJP 31760 Chandoliya Raaj -

Cabinet Nod for Draft Law to Introduce VAT in Qatar

BUSINESS | Page 1 SPORT | Page 1 Tabata, al-Harazi score as INDEX DOW JONES QE NYMEX QATAR 2-15, 32 COMMENT 29, 30 Qatargas delivers REGION 15 BUSINESS 1-7, 12-16 Rayyan 20,924.04 9,955.40 47.68 ARAB WORLD 15, 16 CLASSIFIED 8-11 LNG cargo to new -25.85 -37.44 +0.02 INTERNATIONAL 17-28 SPORTS 1-8 make semis -0.12% -0.37% +0.04% Chinese terminal Latest Figures published in QATAR since 1978 THURSDAY Vol. XXXVIII No. 10443 May 4, 2017 Sha ’baan 8, 1438 AH GULF TIMES www. gulf-times.com 2 Riyals Cabinet nod In brief for draft law QATAR | Offi cial Emir condoles with Saudi King Salman to introduce HH the Emir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani, HH the Deputy Emir Sheikh Abdullah bin Hamad al-Thani and HE the Prime Minister and Interior Minister Sheikh Abdullah bin Nasser VAT in Qatar bin Khalifa al-Thani yesterday sent cables of condolences to Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques King aking another step towards the No 21 of 2009 and Law No 17 of 2014, Salman bin Abdulaziz al-Saud of Saudi implementation of value-added “which exempt the share of non-Qatari Arabia; Crown Prince, Deputy Prime Ttax (VAT) in Qatar, the Cabinet investors in the profi ts of some com- Minister and Minister of Interior Prince yesterday gave its nod to a draft law on panies and investment funds from in- Mohamed bin Nayef bin Abdulaziz al- US President Donald Trump and Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas shake hands in the Roosevelt Room during a joint the proposed new levy and its draft ex- come tax”, QNA said. -

Page2 Obituary.Qxd (Page 3)

SATURDAY, APRIL 27, 2019 (PAGE 4) DAILY EXCELSIOR, JAMMU From page 1 Only 13 out of total 'Efforts to find long-term solution fail to yield desired results' Optimistic of Masood Azhar's listing My Govt exposing duplicity of those 173 candidates in Time has come to review Art 370, 35-A: Rajnath Delhi are women as global terrorist by UN: UK blackmailing through double speak: Modi MUMBAI, Apr 26: gency in the Northeast and ters. NEW DELHI, Apr 26: "We are strong supporter of we were hopeful of coming out tion but conducted Panchayat NEW DELHI, Apr 26: Naxalism in parts of the coun- "Whatever ministers or listing of Azhar. We hope there of this game of blackmailing polls to empower people at the Union Home Minister try, Rajnath said, "Naxal vio- MPs do, they do it after get- The UK today said it was will be conclusion to the issue Only 13 out of the total 173 Rajnath Singh today said that lence in the country is also on ting the team leader's consent, and evolve a solution but it grass root level," he added. candidates fighting the Lok Sabha optimistic that Jaish-e- soon," Asquith added. time has come to review the wane....Insurgency in it is but natural. All policy didn't work since that was our Justifying his Government's election in Delhi are women, put- Mohammed (JeM) chief Masood The fresh proposal to desig- `Mahamilawat' (adulteration) of present policy on Kashmir and ting their share among the total Articles 370 and 35-A of the Northeast is almost finished", decisions are taken under the Azhar will soon be declared a nate Azhar under the 1267 Al two opposite poles," he said describing the same as best number of contestants at a dismal Constitution, which provide adding "we are now in the chairmanship of the Prime global terrorist by the United Qaeda Sanctions Committee of while terming BJP- PDP coali- approach, the Prime Minister seven per cent. -

LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY NATIONAL CAPITAL TERRITORY of DELHI Bulletin Part-I (Brief Summary of Proceedings) Wednesday, 31 May 2017 / 10 Jyeshtha 1939 (Saka ) No

LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY NATIONAL CAPITAL TERRITORY OF DELHI Bulletin Part-I (Brief summary of proceedings) Wednesday, 31 May 2017 / 10 Jyeshtha 1939 (Saka ) No. 50 2.05 PM Sh. Ram Niwas Goel, Hon’ble Speaker in-Chair National Song (Vande Mataram) 1. 2.06 PM Obituary Reference: The House observed two minutes silence on the sad demise of Shri Rampal Karhana, Former Member of the Legislative Assembly of NCT of Delhi (1993-1998). 2. 2.09 PM The Chair greeted Shri Jagdeep Singh, Hon’ble Chief Whip on his Birthday. 3. 2.10 PM Sh. Vijender Gupta, Hon’ble Leader of Opposition sought to know the fate of his notices for Calling Attention and Short Duration Discussion. The Chair stated that as the sitting had been expressly convened to consider “The Delhi Goods and Services Taxes Bill, 2017” he had not allowed any other notices. Not satisfied with the Chair’s ruling, Members of the BJP protested and created disturbances. 4. 2.20 PM Introduction of Ministers: Shri Arvind Kejriwal, Hon’ble Chief Minster introduced the newly appointed Members of the Council of Ministers, Shri Rajendra Pal Gautam and Shri Kailash Gahlot to the House. The Hon’ble Leader of Opposition also expressed his greetings on behalf of his Party to the new Ministers. 5. 2.24PM The Hon’ble Leader of Opposition again sought to raise the issue of shortage of medicines in Government Hospitals. The Hon’ble Deputy Chief Minister made a brief statement on the aforesaid issue. Shri Kapil Mishra displayed a banner and rushed towards the well shouting slogans.