The Exploration of Tibesti, Erdi, Borkou

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download File

Italy and the Sanusiyya: Negotiating Authority in Colonial Libya, 1911-1931 Eileen Ryan Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 ©2012 Eileen Ryan All rights reserved ABSTRACT Italy and the Sanusiyya: Negotiating Authority in Colonial Libya, 1911-1931 By Eileen Ryan In the first decade of their occupation of the former Ottoman territories of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica in current-day Libya, the Italian colonial administration established a system of indirect rule in the Cyrenaican town of Ajedabiya under the leadership of Idris al-Sanusi, a leading member of the Sufi order of the Sanusiyya and later the first monarch of the independent Kingdom of Libya after the Second World War. Post-colonial historiography of modern Libya depicted the Sanusiyya as nationalist leaders of an anti-colonial rebellion as a source of legitimacy for the Sanusi monarchy. Since Qaddafi’s revolutionary coup in 1969, the Sanusiyya all but disappeared from Libyan historiography as a generation of scholars, eager to fill in the gaps left by the previous myopic focus on Sanusi elites, looked for alternative narratives of resistance to the Italian occupation and alternative origins for the Libyan nation in its colonial and pre-colonial past. Their work contributed to a wider variety of perspectives in our understanding of Libya’s modern history, but the persistent focus on histories of resistance to the Italian occupation has missed an opportunity to explore the ways in which the Italian colonial framework shaped the development of a religious and political authority in Cyrenaica with lasting implications for the Libyan nation. -

Provinces De L'ennedi Ouest Et De L'ennedi Est Mars 2021

TCHAD Provinces de l'Ennedi Ouest et de l'Ennedi Est Mars 2021 19°30'0"E 20°0'0"E 20°30'0"E 21°0'0"E 21°30'0"E 22°0'0"E 22°30'0"E 23°0'0"E 23°30'0"E 24°0'0"E Mousso Logoi Localités Tekaro Dfana Louli Ouri-Sao Chef-lieu de province Ehi Kaidou Chef-lieu de département Barkai Tohon Ouana Yangara 21°30'0"N Arasche Horama 21°30'0"N Chef-lieu de sous-préfecture Ouri Sao Angama Camp de réfugiés Enneri Tougoumchi Village vrai Borou Koultimi Ehi Ohade Ohade Infrastructures Bogore Enneri Fofoda Tire-Tacoma Centre de santé Ouaga Kourtima Gara Yasko Antenne reseau téléphonique Ergueme Ounga Gara Toukouli Kayobe Piste d'atterrissage 21°0'0"N Dohobou L I B Y E 21°0'0"N Secondaire Gara Abou Ndougay Tertiaire Tedegra Piste TIBESTI EST Limites administratives Tarou Frontière nationale Ouarou T I B E S T I Limite de province Altipiano di Gef-gef el-Chebir Limite de département 20°30'0"N 20°30'0"N Moura Gara Talehat Ehi Micha Ghere Talha Magan Bezi Yeskimi Djebel Hadid Bobodei Ehi Droussou 20°0'0"N 20°0'0"N Mare de Salem Boudou Tchige Moza Garet el Gorane Yoga Drosso Arkononno Bini Odomanga Korozo Moiounga Gara Louli Dorron Enneri Binem Dor Forria Oued Ouorchille Billinga Kossomia Doudou Siss Arkenoki Oude Bourbou Agotega Bibida Bourdounga Gouro Galkounga Fochi Bezi Kioranga Bibideme Oulemechi Arkenia Tekro 19°30'0"N Aroualli Seguerday 19°30'0"N Seger Mardakilinga Tala Amossri Kei Gara Yeskia Erdi Korko Kouroumai Ouachi Kiroma Kada Bibidozedo Adem Boeina Tordou-Emi Diendale Baisa Anissadeda Kei Douringa Kizimi Arka Erdi Fochimi Marhdogoum Amerouk Tomma -

Journal of Conventional Weapons Destruction Chad

Journal of Conventional Weapons Destruction Volume 10 Issue 1 The Journal of Mine Action Article 18 August 2006 Chad Country Profile Center for International Stabilization and Recovery at JMU (CISR) Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/cisr-journal Part of the Defense and Security Studies Commons, Emergency and Disaster Management Commons, Other Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons, and the Peace and Conflict Studies Commons Recommended Citation Profile, Country (2006) "Chad," Journal of Mine Action : Vol. 10 : Iss. 1 , Article 18. Available at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/cisr-journal/vol10/iss1/18 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for International Stabilization and Recovery at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Conventional Weapons Destruction by an authorized editor of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Profile: Chad COUNTRY PROFILES points in the Borkou-Ennedi-Tibesti region. and coastal areas, swamps make demining As Egypt is a quickly developing and grow- Due to lack of funding, the MAG/UNOPS work difficult, and in the Western Desert, ing country, land will become increasing- contract ended in December 2005 and the sand dunes and wind move and conceal ly important. deminers are waiting for a new contract. The landmines/UXO.6 The aging of UXO items by Megan Wertz deployment of three EOD teams was planned makes them increasingly unsteady and prone Facing the Future [ Mine Action Information Center ] for April 1, 2006, but due to logistical prob- to detonation. -

Ennedi Expedition 1St – 8Th February 2022 Expedition Overview

Ennedi Expedition 1st – 8th February 2022 Expedition Overview 1st February 2022 Radisson Blu Hotel | N’Djamena | Chad 2nd February 2022 N’Djamena to Ennedi Natural and Cultural Reserve 2nd to 8th February 2022 Explore Ennedi Natural and Cultural Reserve 1st to 8th February 2022 8th February 2022 Ennedi Expedtion Ennedi Natural and Cultural Reserve to N’Djamena 1 night Radisson Blu Hotel 4 nights Warda Camp 2 nights Mobile camp A day-to-day breakdown… 1st February 2022 - N’DJAMENA | CHAD On arrival in N’Djamena you will be met by your expedition guide, and your ground team, and road transferred to the Radisson Blu Hotel for the night. Dependent on arrival time you may want to relax in the hotel, experience the N’Djamena horseracing or enjoy relaxing sundowners overlooking the Chari river and Cameroon. 2nd February 2022 - NDJ-FADA-TERKEI | ENNEDI Today we will have an early start before heading to the airport to board our charter flight to Fada. Fada is a characteristic Saharan village and the gateway to Ennedi. On arrival in Fada we’ll meet our expedition team and complete some district formalities before heading out into the vast landscape of the Ennedi Massif. Our route to Warda camp passes a beautiful region of tassilian rock formations, tongues of sand and, in Terkey, we will visit one of the most important rock art sites in the region. After a day of adventure we arrive at Warda camp, our base for the next 3 nights. Dinner and overnight at Warda Camp. A day-to-day breakdown… 3rd February 2022 - NOHI-LABYRINTH-ARCHEI | ENNEDI Today we head out to explore the beautiful and verdant landscape of Wadi Nohi, amazing cave sites rich in paintings, the water formed Oyo labyrinth and finally the incredible wadi Archei. -

Ennedi Expedition 2Nd – 9Th February 2021 Expedition Overview

Ennedi Expedition 2nd – 9th February 2021 Expedition Overview 2nd February 2021 Radisson Blu Hotel | N’Djamena | Chad 3rd February 2021 N’Djamena to Ennedi National Park 3rd – 9th February 2021 Explore Ennedi National Park 2nd – 9th February 2021 9th February 2021 Ennedi Expedtion Ennedi National Park to N’Djamena 2 nights Radisson Blu Hotel 4 nights Warda Camp 2 nights Mobile camp A day-to-day breakdown… 2nd February 2021 - N’DJAMENA | CHAD On arrival in N’Djamena you will be met by your expedition guide, and your ground team, and road transferred to the Radisson Blu Hotel for the night. Dependent on arrival time you may want to relax in the hotel, experience the N’Djamena horseracing or enjoy relaxing sundowners overlooking the Chari river and Cameroon. 3rd February 2021- NDJ-FADA-TERKEI | ENNEDI Today we will have an early start before heading to the airport to board our charter flight to Fada. Fada is a characteristic Saharan village and the gateway to Ennedi. On arrival in Fada we’ll meet our expedition team and complete some district formalities before heading out into the vast landscape of the Ennedi Massif. Our route to Warda camp passes a beautiful region of tassilian rock formations, tongues of sand and, in Terkey, we will visit one of the most important rock art sites in the region. After a day of adventure we arrive at Warda camp, our base for the next 3 nights. Dinner and overnight at Warda Camp. A day-to-day breakdown… 4th February 2021– NOHI-LABYRINTH-ARCHEI | ENNEDI Today we head out to explore the beautiful and verdant landscape of Wadi Nohi, amazing cave sites rich in paintings, the water formed Oyo labyrinth and finally the incredible wadi Archei. -

FAO Desert Locust Bulletin 192 (English)

page 1 / 7 FAO EMERGENCY CENTRE FOR LOCUST OPERATIONS DESERT LOCUST BULLETIN No. 192 GENERAL SITUATION DURING AUGUST 1994 FORECAST UNTIL MID-OCTOBER 1994 No significant Desert Locust populations have been reported during August and the overall situation whilst still requiring vigilance, appears calm, with no major chance to develop during the forecast period. In West Africa, only scattered adults and hoppers were reported limited primarily to southern Mauritania. This would indicate that swarms from northern Mauritania dispersed earlier in the year before the onset of the rainy season and, as a result, breeding in the south was limited. No other significant locust activity has been reported from Mali, Niger and Chad. In South- West Asia, a few patches of hoppers have been treated in Rajasthan over a small area, and low density adults persisting in several locations of the summer breeding areas of India and Pakistan are likely to continue to breed; however, no major developments are expected during the forecast period. A few mature adults have been reported in the extreme south-eastern desert of Egypt and some isolated adults were present on the northern coastal plains of Somalia in late July. No locusts were reported from Sudan, Saudi Arabia, Yemen or Oman. Conditions were reported as dry in Algeria and no locust activity was reported; a similar situation is expected to prevail in Morocco. Although the overall situation does not appear to be critical and may decline in the next few months, FAO recommends continued monitoring in the summer breeding areas. The FAO Desert Locust Bulletin is issued monthly, supplemented by Updates during periods of increased Desert Locust activity, and is distributed by fax, telex, e-mail, FAO pouch and airmail by the Emergency Centre for Locust Operations, AGP Division, FAO, 00100 Rome, Italy. -

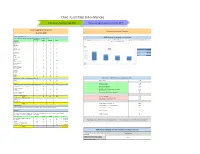

Chad Asset Map (At-A-Glance)

Chad Asset Map (At-a-Glance) Simulation Excercise Q4 2016 Transition plan expected by Q2 2017 Asset Mapping Data Overview General Information Overview As of July 2016 A. Polio Funded Personnel Number of HR per organization and regions involved in polio eradication in Chad GPEI Funding Ramp Down information Ministry of WHO UNICEF Total GPEI budget curve for polio eradication efforts in Chad from 2016-2019,a decrease in the budget from $18,326,000 to $8,097,000, a 56% PROVINCE Health decrease from 2016 to 2019 Niveau central 0 11 7 18 Njamena 0 5 7 12 Bahr Elghazal 0 2 2 4 Batha 0 2 0 2 Borkou 0 0 0 0 Chari Baguirmi 0 5 4 9 Year Funding Amount Dar Sila 0 3 2 5 2016 18,326,000 Ennedi Est 0 0 0 0 2017 12,047,000 Ennedi Ouest 0 0 0 0 2018 9,566,000 Guera 0 2 4 6 2019 8,097,000 Hadjer Lamis 0 1 2 3 Kanem 0 2 4 6 Lac 0 6 5 11 Logone Occidental 0 5 6 11 Logone Oriental 0 2 3 5 Mandoul 0 2 1 3 Mayo Kebbi Est 0 4 2 6 Mayo Kebbi Ouest 0 1 4 5 Moyen Chari 0 6 7 13 Ouaddai 0 3 3 6 Salamat 0 3 2 5 Tandjile 0 0 2 2 Tibesti 0 0 0 0 Wadi Fira 0 2 2 4 TOTAL 0 67 69 136 Time allotments of GPEI funded personnel by priority area in Chad Distribution of HR by Administrative Level of Assignment Central 0 11 7 18 Polio eradication 40.40% Régional 0 56 62 118 TOTAL 0 67 69 136 Routine Immunization 32.40% Distribution of HR involved in polio eradication by functions Measles and rubella 7.30% Implementation and service delivery 0 9 8 17 New vaccine introduction 1.40% Disease Surveillance 0 18 2 20 Child health days or weeks 0.00% Training 0 0 39 39 Maternal, newborn, and child health and nutrition 2.40% Monitoring 0 4 0 4 Health systems strengthening 3.80% Resource mobilization 0 4 2 6 Sub-total immunization related beyond polio 47% Policy and strategy 0 4 3 7 Management and operations 0 28 15 43 TOTAL 0 67 69 136 Sanitation and hygiene 0.50% Polio HR cost per administrative area Natural disasters and humanitarian crises 7.10% Central Level Other diseases or program areas 4.90% Regional Level TOTAL % of personnel formally trained in RI 100% B. -

A Revision of the Anthaxia (Haplanthaxia) Mashuna Species-Group (Coleoptera: Buprestidae: Buprestinae)

ACTA ENTOMOLOGICA MUSEI NATIONALIS PRAGAE Published 15.xii.2014 Volume 54(2), pp. 605–621 ISSN 0374-1036 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:8CDB9964-0571-4CC4-96CA-55D197273B01 A revision of the Anthaxia (Haplanthaxia) mashuna species-group (Coleoptera: Buprestidae: Buprestinae) Svatopluk BÍLÝ1) & Vladimir P. SAKALIAN2) 1) Czech University of Life Sciences, Faculty of Forestry and Wood Sciences, Department of Forest Protection and Entomology, Kamýcká 1176, CZ-165 21, Praha 6 – Suchdol, Czech Republic; e-mail: [email protected] 2) Institute of Biodiversity and Ecosystem Research, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, 1 Tzar Osvoboditel Blvd., 1000, So¿ a, Bulgaria; e-mail: [email protected] Abstract. The Anthaxia (Haplanthaxia) mashuna Obenberger, 1931 species-group is de¿ ned, revised, keyed, and important diagnostic characters are illustrated. Additionally, four new species are described: Anthaxia (Haplanthaxia) convexi- ptera sp. nov. (Ethiopia, Tanzania, Zimbabwe), A. (H.) jendeki sp. nov. (Kenya), A. (H.) nigroaenea sp. nov. (Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda), and A. (H.) puchneri sp. nov. (Angola). The lectotype of Anthaxia (H.) mashuna Obenberger, 1931 is designated. New country records and new host plants are given for Anthaxia (H.) ennediana Descarpentries & Mateu, 1965, A. (H.) mashuna, and A. (H.) patrizii Théry, 1938. Key words. Coleoptera, Buprestidae, Anthaxiini, new species-group, new species, lectotype designation, taxonomy, Afrotropical Region, Palaearctic Region Introduction The Sahelian fauna of the genus Anthaxia was rather poorly known and only a few spe- cies of the Sahelian distribution were recorded in the Obenbergerތs Catalogue (OBENBERGER 1930). The number of species signi¿ cantly increased when DESCARPENTRIES & BRUNEAU DE MIRÉ (1963) and DESCARPENTRIES & MATEU (1965) published the results of the French expe- ditions to Tibesti and Ennedi, respectively. -

Lake Chad Basin

Integrated and Sustainable Management of Shared Aquifer Systems and Basins of the Sahel Region RAF/7/011 LAKE CHAD BASIN 2017 INTEGRATED AND SUSTAINABLE MANAGEMENT OF SHARED AQUIFER SYSTEMS AND BASINS OF THE SAHEL REGION EDITORIAL NOTE This is not an official publication of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). The content has not undergone an official review by the IAEA. The views expressed do not necessarily reflect those of the IAEA or its Member States. The use of particular designations of countries or territories does not imply any judgement by the IAEA as to the legal status of such countries or territories, or their authorities and institutions, or of the delimitation of their boundaries. The mention of names of specific companies or products (whether or not indicated as registered) does not imply any intention to infringe proprietary rights, nor should it be construed as an endorsement or recommendation on the part of the IAEA. INTEGRATED AND SUSTAINABLE MANAGEMENT OF SHARED AQUIFER SYSTEMS AND BASINS OF THE SAHEL REGION REPORT OF THE IAEA-SUPPORTED REGIONAL TECHNICAL COOPERATION PROJECT RAF/7/011 LAKE CHAD BASIN COUNTERPARTS: Mr Annadif Mahamat Ali ABDELKARIM (Chad) Mr Mahamat Salah HACHIM (Chad) Ms Beatrice KETCHEMEN TANDIA (Cameroon) Mr Wilson Yetoh FANTONG (Cameroon) Mr Sanoussi RABE (Niger) Mr Ismaghil BOBADJI (Niger) Mr Christopher Madubuko MADUABUCHI (Nigeria) Mr Albert Adedeji ADEGBOYEGA (Nigeria) Mr Eric FOTO (Central African Republic) Mr Backo SALE (Central African Republic) EXPERT: Mr Frédèric HUNEAU (France) Reproduced by the IAEA Vienna, Austria, 2017 INTEGRATED AND SUSTAINABLE MANAGEMENT OF SHARED AQUIFER SYSTEMS AND BASINS OF THE SAHEL REGION INTEGRATED AND SUSTAINABLE MANAGEMENT OF SHARED AQUIFER SYSTEMS AND BASINS OF THE SAHEL REGION Table of Contents 1. -

Chad: Defusing Tensions in the Sahel

Chad: Defusing Tensions in the Sahel $IULFD5HSRUW1 _ 'HFHPEHU 7UDQVODWLRQIURP)UHQFK +HDGTXDUWHUV ,QWHUQDWLRQDO&ULVLV*URXS $YHQXH/RXLVH %UXVVHOV%HOJLXP 7HO )D[ EUXVVHOV#FULVLVJURXSRUJ Preventing War. Shaping Peace. Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Ambivalent Relations with N’Djamena ............................................................................ 3 A. Relations between the Sahel Regions and Central Government since the 1990s ..... 3 1. Kanem ................................................................................................................... 3 2. Bahr el-Ghazal (BEG) ........................................................................................... 5 B. C0-option: A Flawed Strategy .................................................................................... 6 III. Mounting Tensions in the Region .................................................................................... 8 A. Abuses against BEG and Kanem Citizens .................................................................. 8 B. A Regional Economy in the Red ................................................................................ 9 C. Intra-religious Divides ............................................................................................... 11 IV. The -

Lake Chad Basin Crisis Regional Market Assessment June 2016 Data Collected January – February 2016

Lake Chad Basin Crisis Regional Market Assessment June 2016 Data collected January – February 2016 Acknowledgments This study was prepared by Stephanie Brunelin and Simon Renk. Primary data was collected in collaboration with ACF and other partners, under the overall supervision of Simon Renk. Acknowledgments go to Abdoulaye Ndiaye for the maps and to William Olander for cleaning the survey data. The mission wishes to acknowledge valuable contributions made by various colleagues in WFP country office Chad and WFP Regional Bureau Dakar. Special thanks to Cecile Barriere, Yannick Pouchalan, Maggie Holmesheoran, Patrick David, Barbara Frattaruolo, Ibrahim Laouali, Mohamed Sylla, Kewe Kane, Francis Njilie, Analee Pepper, Matthieu Tockert for their detailed and useful comments on earlier versions of the report. The report has also benefitted from the discussions with Marlies Lensink, Malick Ndiaye and Salifou Sanda Ousmane. Finally, sincere appreciation goes to the enumerators, traders and shop-owners for collecting and providing information during the survey. Acronyms ACF Action Contre la Faim ACLED Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project FAO Food and Agriculture Organization FEWS NET Famine Early Warning System Network GDP Gross Domestic Product GPI Gender Parity Index IDP Internally Displaced People IFC International Finance Corporation IMF International Monetary Fund IOM International Organization for Migration MT Metric Ton NAMIS Nigeria Agricultural Market Information Service OHCHR Office of the United Nations High Commissioner -

Chapter 1 Present Situation of Chad's Water Development and Management

1 CONTEXT AND DEMOGRAPHY 2 With 7.8 million inhabitants in 2002, spread over an area of 1 284 000 km , Chad is the 25th largest 1 ECOSI survey, 95-96. country in Africa in terms of population and the 5th in terms of total surface area. Chad is one of “Human poverty index”: the poorest countries in the world, with a GNP/inh/year of USD 2200 and 54% of the population proportion of households 1 that cannot financially living below the world poverty threshold . Chad was ranked 155th out of 162 countries in 2001 meet their own needs in according to the UNDP human development index. terms of essential food and other commodities. The mean life expectancy at birth is 45.2 years. For 1000 live births, the infant mortality rate is 118 This is in fact rather a and that for children under 5, 198. In spite of a difficult situation, the trend in these three health “monetary poverty index” as in reality basic indicators appears to have been improving slightly over the past 30 years (in 1970-1975, they were hydraulic infrastructure respectively 39 years, 149/1000 and 252/1000)2. for drinking water (an unquestionably essential In contrast, with an annual population growth rate of nearly 2.5% and insufficient growth in agricultural requirement) is still production, the trend in terms of nutrition (both quantitatively and qualitatively) has been a constant insufficient for 77% of concern. It was believed that 38% of the population suffered from malnutrition in 1996. Only 13 the population of Chad.