Unrevised Transcript of Evidence Taken Before

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Great Britain May 19 – 29, 1995

Great Britain May 19 – 29, 1995 Friday/Saturday, May 19–20 – Los Angeles to London After a full day at work and a Santa Monica “Tommy’s Run” with our RAND co-worker Edson Smith (double chili-cheeseburgers, yum!), we got ourselves to the airport and on our British Airways flight. Claire and Alla were on our flight, too; they arrived at the airport, a little later than advised, with Ken and Rod. Both Robert and I were curious as to how the encounter with Rod would go; turned out not so bad, just a little tentative (I certainly had very little to say). After six years, what could one expect? At any rate, Claire and Alla did not get seats together, and wanted to try to fix that, so we left Ken and Rod at the security checkpoint pretty quickly and went to the departure gate. There Claire and Alla did manage to get their seats rearranged and wound up together just a few rows behind us. The flight left about 20 minutes late, at 9:30 PM, and I enjoyed six good hours of sleep 1, missing the food service, but awaking to find Immortal Beloved playing. How perfect it seemed; enjoying German music on a British flight. It really made me look forward to seeing Johannes Weissler and his very British brother Ulrich! We arrived at Heathrow at 3:35 PM local time Saturday. We had a very speedy pass through customs; it was probably an advantage coming into British Airways dedicated international terminal (#4), with most passengers on the flight having European Community (EC) passports. -

Getting Settled 2017.Pdf

Contents Your New Life in the TASIS England Area 3 I. Finding A Home 4 II. Interim Living 7 III. Getting Around 9 IV. Assistance with Settling: The Emotional and Practical Sides to Relocation 11 Top TASIS Towns 12 Parents’ Information and Resource Committee 32 PIRC: Helping TASIS Families Transition 32 Summer Opportunities 34 Banking 35 Telephone, Mobile Phone, Television & Internet Service 36 Medical Care 39 U.K. Driving 40 Faith Communities 41 Before You Arrive in the U.K. 44 Living in England Special Section from AWBS International Women’s Club 46 1 2 Your New Life in the TASIS England Area All information and links contained here were current at the time the document was com- piled. TASIS The American School in England cannot endorse specific businesses or individuals. The options are listed to augment and facilitate your own investigations. Please consider all options carefully, before making important decisions based on this limited information. If you find that any information listed here is in error, please contact communications@tasisen- gland.org. TOP TASIS TOWNS Virginia Water Weybridge Ascot Sunningdale Walton-on-Thames Egham Englefield Green Woking Windsor Richmond Windlesham Sunninghill These are the most popular towns, because of their locations, amongst TASIS families. Information about each town can be found in the Top TASIS Towns section, beginning on page 12. 3 I. FINDING A HOME The following websites provide listings of properties, including descriptions and prices, available within a particular town or postcode. Typically, you can narrow your search by number of bedrooms, price range, etc. These websites are not affiliated with a particular estate agency: www.primelocation.com www.rightmove.co.uk www.zoopla.co.uk ESTATE AGENTS Rental properties are referred to as “lets,”and agents with rentals are “letting agents.” There is no multi-listing of available properties in England. -

Annual Report 2004/5 Corrected

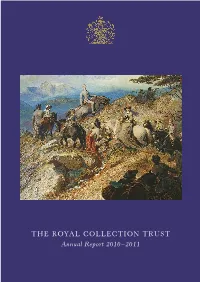

THE ROYAL COLLECTION TRUST Annual Report 201 0–2011 AIMS OF THE ROYAL COLLECTION TRUST In fulfilling the Trust’s objectives, the Trustees’ aims are to ensure that: • the Royal Collection (being the works of art held by The Queen in right of the crown and held in trust for her successors and for the nation) is subject to proper custodial control and that the works of art remain available to future generations; • the Royal Collection is maintained and conserved to the highest possible standards and that visitors can view the Collection in the best possible condition; • as much of the Royal Collection as possible can be seen by members of the public; • the Royal Collection is presented and interpreted so as to enhance public appreciation and understanding; • access to the Royal Collection is broadened and increased (subject to capacity constraints) to ensure that as many people as possible are able to view the Collection; • appropriate acquisitions are made when resources become available, to enhance the Collection and displays of exhibits for the public. When reviewing future activities, the Trustees ensure that these aims continue to be met and are in line with the Charity Commission’s General Guidance on public benefit. This report looks at the achievements of the previous 12 months and considers the success of each key activity and how it has helped enhance the benefit to the nation. FRONT COVER : Carl Haag (182 0–1915), Morning in the Highlands: the Royal Family ascending Lochnagar , 1853 (detail). A Christmas present from Prince Albert to Queen Victoria, the painting was included in the exhibition Victoria & Albert: Art & Love , at The Queen’s Gallery, Buckingham Palace, from March to December 2010. -

Windsor Great Park and Woodlands

Berkshire Conservation Target Areas Descriptions.doc Windsor Great Park and Woodlands This area includes Windsor Great Park SSSI along with adjacent parkland and various areas to the south with similar habitats including Silwood Park, some large woodlands, Ascot racecourse and a number of sites on the edge of Ascot. Joint Character Area: Thames Valley. The southern edge is in the Thames Basin Heaths Area. Geology: the northern area including most of Windsor Great Park is London Clay Formation clay, silt and sand. In the south there are low hills and other areas, with areas of Bagshot Sand and topped by River Terrace Sand ands Gravels and with some bands of Head. Topography: relatively flat in the north with a mixture of low hills, gently sloping valley sides and flatter areas in the south. Biodiversity: Parkland and Wood Pasture: Windsor Great Park is an extensive area of parkland and old wood pasture with large numbers of veteran trees. These support important specialist invertebrate and fungi populations. Further parkland is found to the north- west of the area. Parkland habitat is also found at Silwood Park. Woodland: There are extensive areas of woodland. Many areas are ancient woodland though significant areas have been replanted in the past. In the wet valleys there is wet woodland with extensive areas at Silwood Park. Acid Grassland: there are areas of acid grassland, especially in Windsor Great Park with remnants elsewhere. Lowland Meadow: There are areas of lowland meadow habitat in Windsor Great Park and also extensive remnants of this habitat. Standing Water: There are a variety of water bodies ranging from small ponds to large lakes, such as Virginia Water. -

Event Organiser Location Total Cost Ascot Races Ascot Race Authority

Event Organiser Location Total Cost Ascot Races Ascot Race Authority Ascot Racecourse, High Street, Ascot, Berkshire 3,608.00 Eton Celebrations Eton College Eton College, Eton, Windsor 4,963.20 Royal Ascot Ascot Racecourse Ltd Ascot Racecourse, High Street, Ascot, Berkshire 367,477.00 Cartier International Polo Guards Polo Club Windsor Great Park 5,033.60 Salt Hill Part Urban Dance Festival Slough Borough Council Slough 6,406.40 Windsor Races Royal Windsor Racecourse Royal Windsor Racecourse, Windsor 440.00 Filming at Eton Casino Royal Productions Ltd Eton 1,622.50 Windsor Races Royal Windsor Racecourse Royal Windsor Racecourse, Windsor 440.00 South Hill Park Bracknell 713.90 Shergar Cup Ascot Race Authority Ascot Racecourse, High Street, Ascot, Berkshire 4,432.00 Windsor Races Royal Windsor Racecourse Royal Windsor Racecourse, Windsor 440.00 Diamond Day Weekend Ascot Race Authority Ascot Racecourse, High Street, Ascot, Berkshire 21,872.00 Slough Fireworks Slough Borough Council Upton Court Park 275.00 Royal Windsor Triathlon Human Race Ltd Windsor 7,000.00 Legoland Fireworks Night Legoland Windsor 400.00 Legoland Fireworks Night Legoland Windsor 600.00 Filming in Slough High St TXTV Ltd High St, Slough 275.00 Pakistani Welfare Association Elections Montem Primary School, Slough 2,567.00 Reading Half Marathon Bradshaw Leisure Ltd Reading 4,380.00 Reading Football Club Promotion Parade Reading Borough Council Reading 3,554.00 Reading v QPR Reading Football Club Madejski Stadium 10,684.00 England v Belarus Reading Football Club Madejski -

Source : Bibliothèque Du CIO / IOC Library Source : Bibliothèque Du CIO / IOC Library XIV OLYMPIAD

Source : Bibliothèque du CIO / IOC Library Source : Bibliothèque du CIO / IOC Library XIV OLYMPIAD Source : Bibliothèque du CIO / IOC Library THE OFFICIAL REPORT OF THE ORGANISING COMMITTEE FOR THE XIV OLYMPIAD > PUBLISHED BY THE ORGANISING COMMITTEE FOR THE XIV OLYMPIAD • LONDON · 1948 HIS MAJESTY KING GEORGE VI Source : Bibliothèque du CIO / IOC Library COPYRIGHT - 1951 BY THE ORGANISING COMMITTEE FOR THE XIV OLYMPIAD • LONDON • 1948 t HE spirit of the Oljmpic Games, which has tarried here awhile, sets forth once more. Maj it prosper throughout the world, saje in the keeping of all those who have felt its noble impulse in this great Festival of Sport." i i LORD BURGHLEY, Chairman of the Organising Committee, for the scoreboard at the Closing Ceremony, August 14, 1948. Printed by McCorquodale & Co. Ltd., St. Thomas Street, London, S.E.i Source : Bibliothèque du CIO / IOC Library INTRODUCTION By the General Editor, The Kight Hon. The Lord Burghley, K.C.M.G. N the production and presentation of this Official Report, the Organising Committee has endeavoured to satisfy two primary objects : that the matter shall be, as far as I possible, accurate, and that it shall serve not only as a record of the work leading up to the staging of the London Games of 1948, and of the competitions themselves, but also that it may be of assistance to future Organising Committees in their work. The arrangement of the matter has been dictated, apart from the Results sections and those articles dealing with the celebration of the actual Games themselves, by the arrange ment of the work of the departments of the Organising Committee which it was found necessary to create. -

THE RIVER THAMES a Complete Guide to Boating Holidays on the UK’S Most Famous River the River Thames a COMPLETE GUIDE

THE RIVER THAMES A complete guide to boating holidays on the UK’s most famous river The River Thames A COMPLETE GUIDE And there’s even more! Over 70 pages of inspiration There’s so much to see and do on the Thames, we simply can’t fit everything in to one guide. 6 - 7 Benson or Chertsey? WINING AND DINING So, to discover even more and Which base to choose 56 - 59 Eating out to find further details about the 60 Gastropubs sights and attractions already SO MUCH TO SEE AND DISCOVER 61 - 63 Fine dining featured here, visit us at 8 - 11 Oxford leboat.co.uk/thames 12 - 15 Windsor & Eton THE PRACTICALITIES OF BOATING 16 - 19 Houses & gardens 64 - 65 Our boats 20 - 21 Cliveden 66 - 67 Mooring and marinas 22 - 23 Hampton Court 68 - 69 Locks 24 - 27 Small towns and villages 70 - 71 Our illustrated map – plan your trip 28 - 29 The Runnymede memorials 72 Fuel, water and waste 30 - 33 London 73 Rules and boating etiquette 74 River conditions SOMETHING FOR EVERY INTEREST 34 - 35 Did you know? 36 - 41 Family fun 42 - 43 Birdlife 44 - 45 Parks 46 - 47 Shopping Where memories are made… 48 - 49 Horse racing & horse riding With over 40 years of experience, Le Boat prides itself on the range and 50 - 51 Fishing quality of our boats and the service we provide – it’s what sets us apart The Thames at your fingertips 52 - 53 Golf from the rest and ensures you enjoy a comfortable and hassle free Download our app to explore the 54 - 55 Something for him break. -

In Windsor Great Park

Cycling in Windsor Great Park Cycling in Windsor Great Park Rules of the road The great expanse of Windsor Great Park makes it an You must always adhere to the Highway Code when cycling in the Park, and show care and consideration ideal location to explore on bicycle. Motor vehicles for other road users. You must also conform to the Park and motor cycles are restricted, so apart from the Bylaws, displayed at every entry gate. occasional Estate or Park resident vehicle, you will often enjoy generally vehicle-free roads. When cycling in Windsor Great Park, please slow down for and, where necessary, give way to: Please note that parts of the Park can become • Pedestrians extremely busy at times. On major event days, especially those focussed on Smiths Lawn and • Motor vehicles Guards Polo Club, there can be considerable vehicle • Horse riders movements, especially between Blacknest Gate and • Animals Smiths Lawn. Please take special care in these areas, especially if cycling with children. Please keep to the left when cycling, do not ride more than 6 to a group and 2 abreast, and in all other respects follow the rules as if you were cycling on a public road. The National Cycle Route 4 passes through Windsor The Crown Estate Office Great Park, and there is an extensive network of Please take special care near children or dogs, and if Windsor Great Park roads along which cycling is permitted. necessary dismount to pass by safely. Windsor Berkshire SL4 2HT This leaflet is intended to make your cycling Cyclists must not, at any time, exercise dogs whilst Tel: 01753 860 222 during office hours cycling. -

International Newspapers

NewspaperDirect Content Availability Schedule Most Number of Min Max Issue CID Title Issue Ready at Country Language Freq Schedule Hours before Pages Pages Count Pages deadline 2573 24 Heures Montreal 07:40 (0) Canada French 24 48 40 22 -MTWTF- Daily -07:40 0558 24sata 02:05 (0) Croatia Croatian 64 80 68 30 SMTWTFS Weekly -02:05 0527 24sata - Cafe 24 01:50 (0) Croatia Croatian 64 64 64 5 -----F- Weekly -01:50 0241 7 dney 17:00 (+1) Belarus Russian 32 32 32 3 ----T-- Weekly 07:00 2501 A Verdade 04:30 (0) Portugal Portuguese 24 40 40 2 ----T-- Weekly -04:30 3624 Aalener Nachrichten 00:00 (0) Germany German 28 56 32 26 -MTWTFS Daily -00:00 4873 Aarthik Abhiyan 06:00 (0) Nepal Nepali 12 16 12 25 SMTWTF- Daily -06:00 2238 ABC - Alfa y Omega 00:20 (0) Spain Spanish 28 28 28 5 ----T-- Weekly -00:20 ED61 ABC - Alfa y Omega Madrid 00:20 (0) Spain Spanish 28 28 28 5 ----T-- Daily -00:20 2209 ABC - Cultural 03:10 (0) Spain Spanish 28 28 28 4 ------S Weekly -03:10 2208 ABC - Empresa 03:10 (0) Spain Spanish 24 32 24 4 S------ Weekly -03:10 3868 ABC - Especiales 23:50 (0) Spain Spanish 12 84 16 7 SMTWTFS Monthly -23:50 E613 ABC - Especiales Andalucía 08:55 (0) Spain Spanish 92 92 92 1 SMTWTFS Monthly -08:55 2211 ABC - Motor 02:50 (0) Spain Spanish 16 16 16 1 -----FS Monthly -02:50 2212 ABC - Natural 12:55 (+1) Spain Spanish 16 16 16 2 SMTWTFS Monthly 11:05 E152 ABC - Pasion 05:30 (0) Spain Spanish 68 100 68 2 ----T-- Monthly -05:30 2214 ABC - Salud 03:05 (0) Spain Spanish 28 28 28 1 ------S Weekly -03:05 2207 ABC - Vela 00:50 (0) Spain Spanish 16 16 -

Heathrow/Windsor Marriott

Heathrow/Windsor Marriott Hotel Phone: +44 1753 544244 Ditton Road, Langley Fax: +44 1753 540272 Slough, SL3 8PT United Kingdom Sales: +44 1753 544244 Sales fax: +44 1753 598157 Arrival Information Check-in and Check-out Internet Access Check-in: 3:00 PM Guest rooms: Wireless Check-out: 12:00 PM High Speed: Check email + browse the Web for 12.0 Express Checkin, Express Checkout GBP/day Enhanced High Speed: Video chat, download large files + stream video for 20.0 GBP/day Lobby and public areas: Complimentary Wireless Meeting rooms: Wireless, Wired Parking Property Details Electric car charging stations: 1, For a fee 10 GBP 5 floors, 376 Rooms, 6 suites daily 19 meeting rooms, 15,037 sq ft of total meeting space On-site parking, fee: 15 GBP daily Pet Policy Smoke-free Policy Pets not allowed This hotel has a smoke-free policy Services & Amenities All public areas non-smoking Car Rental Concierge Lounge Hours Vending machines Buffet breakfast, fee from: 16.95 GBP Cash machine/ATM Concierge desk Continental breakfast, fee from: 15.95 GBP Housekeeping service daily Laundry on-site Mobility accessible rooms Newspaper delivered to room, on request Room service Room service, 24-hour Safe deposit boxes, front desk Valet dry-cleaning Virtual Concierge Available Guest Room Information General Room Amenities Bathroom Amenities Air conditioning Bathrobe Bottled water: Fee Bathroom amenities Coffee maker/tea service Hair dryer Crib/Play Yard Individual climate control Room Entertainment Cable channel: CNN Iron and ironing board Cable/satellite TV Luxurious -

Download Our Getting Settled Guide

American Express proudly sponsors this practical guide. TASIS England is pleased to accept the American Express Card for school fee payments. Contents Preparing for: Your New Life in the TASIS England Area 1 I. Finding a Home 2 II. Interim Living 6 III. Getting Around 8 Top TASIS Towns 10 Assistance with Settling: The Emotional and Practical Sides to Relocation 33 Parents’ Information and Resource Committee (PIRC) Resources 35 Preparing for an International Move 36 Local Expat Organizations 40 Land and People 41 Important Contact Information 44 Medical Care 45 Banking 48 Telephone, Mobile Phone, Internet Service, and Television 49 Driving 54 Public Transportation 57 Household 59 Kennels/Catteries 61 Postal Services 62 Shopping 63 Faith Communities in the TASIS Area 67 Family Fun 69 Sept20 Your New Life in the TASIS England Area All information and links contained here were current at the time this document was compiled. TASIS The American School in England cannot endorse specific businesses or individuals. The options are listed to augment and facilitate your own investigations. Please consider all options carefully before making important decisions based on this limited information. If you find that any information listed here is in error, please contact [email protected]. TOP TASIS TOWNS Virginia Water Weybridge Ascot Walton-on-Thames Egham Sunningdale Richmond Englefield Green Windsor Woking Sunninghill Windlesham These are the most popular towns among TASIS families because of their locations. Information about each town can be found in the Top TASIS Towns section, beginning on page 10. 1 I. FINDING A HOME The following websites provide listings of properties, including descriptions and prices, available within a particular town or postcode. -

Holidays and Great Value Breaks OVER 135 HOLIDAYS to CHOOSE

Winter/Spring 2018/2019 www.blakescoaches.co.uk BlakesHolidays and Great Value BreaksOVER 135 HOLIDAYS TO CHOOSE FROM Travel with Blakes... travel with friends welcome where to book Departure points COACH SEATING PLAN DEVON OTTERY ST MARY WATCHET Outside Boots The Cross BIDEFORD Kingsley Statue BRIXHAM WILLITON Bank Lane, Outside Outside Gliddons 1 2 3 4 Holidays BRAUNTON Strand Bakery It gives us great pleasure to present our new and Opposite George Hotel BRIDGWATER PAIGNTON Bridgwater Services, 5 6 7 8 exciting 2018/2019 Winter & Spring brochure TORRINGTON (4 day Garfield Road Jct 24 M5 featuring a wide range of quality and value for tours and over) PRESTON BURNHAM-ON-SEA 9 10 11 12 money holidays both within the UK and Europe. Hatchmoor Lane 9 10 11 12 (by school car park) Bus Shelter Ben Travers Way, Tesco and satisfaction are of great importance to us. We (main entrance) BARNSTAPLE TORQUAY 13 14 15 16 value your business and want you to holiday with us The Railway Station Lymington Road WESTON-SUPER-MARE on more than one occasion. Coach Station Bus Stop behind SOUTH MOLTON 17 18 19 20 Parish Pump Pub 17 18 19 20 We have enhanced our holiday programme to bring The Square KINGSKERSWELL Jurys Corner BRISTOL Gordano you the best of established values, retained by KNOWSTONE Bus Stop Services Jct 19 M5 21 22 TOILET popular demand, and a selection of new ideas if you Picnic Area NEWTON ABBOT (Northbound are looking for something different, including new TIVERTON The Railway Station tours only) 23 24 European destinations.