Tumour Antigens Recognized by T Lymphocytes: at the Core of Cancer Immunotherapy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Effects of Chemotherapy Agents on Circulating Leukocyte Populations: Potential Implications for the Success of CAR-T Cell Therapies

cancers Review Effects of Chemotherapy Agents on Circulating Leukocyte Populations: Potential Implications for the Success of CAR-T Cell Therapies Nga T. H. Truong 1, Tessa Gargett 1,2,3, Michael P. Brown 1,2,3,† and Lisa M. Ebert 1,2,3,*,† 1 Translational Oncology Laboratory, Centre for Cancer Biology, University of South Australia and SA Pathology, North Terrace, Adelaide, SA 5000, Australia; [email protected] (N.T.H.T.); [email protected] (T.G.); [email protected] (M.P.B.) 2 Cancer Clinical Trials Unit, Royal Adelaide Hospital, Port Rd, Adelaide, SA 5000, Australia 3 Adelaide Medical School, University of Adelaide, North Terrace, Adelaide, SA 5000, Australia * Correspondence: [email protected] † These authors contributed equally. Simple Summary: CAR-T cell therapy is a new approach to cancer treatment that is based on manipulating a patient’s own T cells such that they become able to seek and destroy cancer cells in a highly specific manner. This approach is showing remarkable efficacy in treating some types of blood cancers but so far has been much less effective against solid cancers. Here, we review the diverse effects of chemotherapy agents on circulating leukocyte populations and find that, despite some negative effects over the short term, chemotherapy can favourably modulate the immune systems of cancer patients over the longer term. Since blood is the starting material for CAR-T cell Citation: Truong, N.T.H.; Gargett, T.; production, we propose that these effects could significantly influence the success of manufacturing, Brown, M.P.; Ebert, L.M. -

Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans in a Male Infant

Pediatric Case Reports Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans in a Male Infant Leslie Peard, Nicholas G. Cost, and Amanda F. Saltzman Dermtofibrosarcoma protuberans is a rare cutaneous malignancy known to be locally aggressive. It is uncommonly seen in the pediatric population and can be difficult to distinguish from other benign skin lesions. We present a case of dermatofi- brosarcoma protuberans of the penis in a 6-month-old child managed with surgical resection. This case highlights the challenges of diagnosis of genital lesions in children and the complexities of genitourinary reconstruction following surgical resection. UROLOGY 129: 206−209, 2019. © 2018 Elsevier Inc. ermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP) is a and no frozen section was sent intraoperatively. The rare cutaneous malignancy with reported foreskin was not sent to pathology per institutional D annual incidence of 4.2 per million (0.3 to practice. 1.3 per million in pediatric patients) in the United Pathologic evaluation by a dermatopathologist revealed States. Patients are typically 20-50 years old. DFSP a CD34+ spindle cell neoplasm, favoring DFSP, with most commonly occurs on the trunk, and is very rarely involvement of deep and “lateral” margins (again, the found on the genitalia.1 To our knowledge, only four specimen was not orientated). FISH for the chromosomal cases of penile DFSP have been reported.2-4 The tumor translocation t(17,22) was negative. CT chest obtained is locally aggressive, with few reported cases of metas- for staging was negative for metastasis. After discussion at tasis.1 There is a paucity of data concerning character- multidisciplinary tumor board, options for management istics of disease and treatment strategies with only 2 proposed included Mohs surgery under local anesthesia by published guidelines available to guide management.5,6 dermatology versus wide local excision with frozen section We present a case of DFSP of the penis in an infant, under general anesthesia by urology. -

Monoclonal Antibody Therapeutics and Apoptosis

Oncogene (2003) 22, 9097–9106 & 2003 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0950-9232/03 $25.00 www.nature.com/onc Monoclonal antibody therapeutics and apoptosis Dale L Ludwig*,1, Daniel S Pereira1, Zhenping Zhu1, Daniel J Hicklin1 and Peter Bohlen1 1ImClone Systems Incorporated, 180 Varick Street, New York, NY 10014, USA The potential for disease-specific targeting and low including the generation of human antibody phage toxicity profiles have made monoclonal antibodies attrac- display libraries, human immunoglobulin-producing tive therapeutic drug candidates. Antibody-mediated transgenic mice, and directed affinity maturation meth- target cell killing is frequently associated with immune odologies, have further improved on the efficiency, effector mechanisms such as antibody-directed cellular specificity, and reactivity of monoclonal antibodies for cytotoxicity, but they can also be induced by apoptotic their target antigens (Schier et al., 1996; Mendez et al., processes. Antibody-directed mechanisms, including anti- 1997; de Haard et al., 1999; Hoogenboom and Chames, gen crosslinking, activation of death receptors, and 2000; Knappik et al., 2000). As a result, the isolation of blockade of ligand-receptor growth or survival pathways, high-affinity fully human monoclonal antibodies is now can elicit the induction of apoptosis in targeted cells. commonplace. Owing to their inherent specificity for a Depending on their mechanism of action, monoclonal particular target antigen, monoclonal antibodies pro- antibodies can induce targeted cell-specific killing alone or mise precise selectivity for target cells, avoiding non- can enhance target cell susceptibility to chemo- or reacting normal cells. radiotherapeutics by effecting the modulation of anti- To be effective as therapeutics for cancer, antibodies apoptotic pathways. -

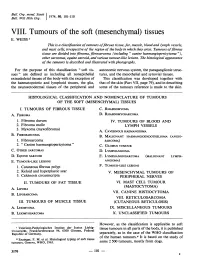

Mesenchymal) Tissues E

Bull. Org. mond. San 11974,) 50, 101-110 Bull. Wid Hith Org.j VIII. Tumours of the soft (mesenchymal) tissues E. WEISS 1 This is a classification oftumours offibrous tissue, fat, muscle, blood and lymph vessels, and mast cells, irrespective of the region of the body in which they arise. Tumours offibrous tissue are divided into fibroma, fibrosarcoma (including " canine haemangiopericytoma "), other sarcomas, equine sarcoid, and various tumour-like lesions. The histological appearance of the tamours is described and illustrated with photographs. For the purpose of this classification " soft tis- autonomic nervous system, the paraganglionic struc- sues" are defined as including all nonepithelial tures, and the mesothelial and synovial tissues. extraskeletal tissues of the body with the exception of This classification was developed together with the haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues, the glia, that of the skin (Part VII, page 79), and in describing the neuroectodermal tissues of the peripheral and some of the tumours reference is made to the skin. HISTOLOGICAL CLASSIFICATION AND NOMENCLATURE OF TUMOURS OF THE SOFT (MESENCHYMAL) TISSUES I. TUMOURS OF FIBROUS TISSUE C. RHABDOMYOMA A. FIBROMA D. RHABDOMYOSARCOMA 1. Fibroma durum IV. TUMOURS OF BLOOD AND 2. Fibroma molle LYMPH VESSELS 3. Myxoma (myxofibroma) A. CAVERNOUS HAEMANGIOMA B. FIBROSARCOMA B. MALIGNANT HAEMANGIOENDOTHELIOMA (ANGIO- 1. Fibrosarcoma SARCOMA) 2. " Canine haemangiopericytoma" C. GLOMUS TUMOUR C. OTHER SARCOMAS D. LYMPHANGIOMA D. EQUINE SARCOID E. LYMPHANGIOSARCOMA (MALIGNANT LYMPH- E. TUMOUR-LIKE LESIONS ANGIOMA) 1. Cutaneous fibrous polyp F. TUMOUR-LIKE LESIONS 2. Keloid and hyperplastic scar V. MESENCHYMAL TUMOURS OF 3. Calcinosis circumscripta PERIPHERAL NERVES II. TUMOURS OF FAT TISSUE VI. -

Mast-Cell Tumors

Glendale Animal Hospital 623-934-7243 familyvet.com Mast-Cell Tumors Basics OVERVIEW • Cancerous (known as “malignant”) round cell tumor; round cell tumors are made up of cells that appear round or oval on microscopic examination; mast-cell tumors are one type of round cell tumor • Tumor arising from mast cells • “Cutaneous” refers to the skin • Mast cells are connective tissue cells that contain very dark granules; the granules contain various chemicals, including histamine; they are involved in immune reactions and inflammation; mast cells can be found in various tissues throughout the body • Mast-cell tumors in dogs are graded as well differentiated or low grade (Grade 1), intermediately differentiated (Grade 2), and poorly differentiated, undifferentiated or high grade (Grade 3); in general, the more differentiated the mast-cell tumor, the better the prognosis • Differentiation is a determination of how much a particular tumor cell looks like a normal cell; the more differentiated, the more like the normal cell • Mast-cell tumors of the skin in cats are classified as “compact” (more benign behavior) or “diffuse” (more undifferentiated and aggressive) • Mast-cell tumors are the most common cancerous (malignant) skin tumor in the dog • Mast-cell tumors also may be found in the tissue immediately beneath the skin (that is, the subcutis), spleen, liver, and intestines • Mast-cell tumors are the most common tumor found in the spleen of cats • Mast-cell tumors can release histamine, leading to the development of hives, reddening of the -

SEREX Analysis for Tumor Antigen Identification in a Mouse Model Of

© 2000 Nature America, Inc. 0929-1903/00/$15.00/ϩ0 www.nature.com/cgt SEREX analysis for tumor antigen identification in a mouse model of adenocarcinoma Tracy A. Hampton,1–3 Robert M. Conry,2 M. B. Khazaeli,2 Denise R. Shaw,2 David T. Curiel,1,2 Albert F. LoBuglio,2 and Theresa V. Strong1–3 1Gene Therapy Center, 2Division of Hematology/Oncology, Department of Medicine, and 3Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Genetics, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama 35294. Evaluation of immunotherapy strategies in mouse models of carcinoma is hampered by the limited number of known murine tumor antigens (Ags). Although tumor Ags can be identified based on cytotoxic T-cell activation, this approach is not readily accomplished for many tumor types. We applied an alternative strategy based on a humoral immune response, SEREX, to the identification of tumor Ags in the murine colon adenocarcinoma cell line MC38. Immunization of syngeneic C57BL/6 mice with MC38 cells by three different methods induced a protective immune response with concomitant production of anti-MC38 antibodies. Immunoscreening of an MC38-derived expression library resulted in the identification of the endogenous ecotropic leukemia virus envelope (env) protein and the murine ATRX protein as candidate tumor Ags. Northern blot analysis demonstrated high levels of expression of the env transcript in MC38 cells and in several other murine tumor cell lines, whereas expression in normal colonic epithelium was absent. ATRX was found to be variably expressed in tumor cell lines and in normal tissue. Further analysis of the expressed env sequence indicated that it represents a nonmutated tumor Ag. -

Immune Escape Mechanisms As a Guide for Cancer Immunotherapy Gregory L

Published OnlineFirst December 12, 2014; DOI: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1860 Perspectives Clinical Cancer Research Immune Escape Mechanisms as a Guide for Cancer Immunotherapy Gregory L. Beatty and Whitney L. Gladney Abstract Immunotherapy has demonstrated impressive outcomes for exploited by cancer and present strategies for applying this some patients with cancer. However, selecting patients who are knowledge to improving the efficacy of cancer immunotherapy. most likely to respond to immunotherapy remains a clinical Clin Cancer Res; 21(4); 1–6. Ó2014 AACR. challenge. Here, we discuss immune escape mechanisms Introduction fore, promote tumor outgrowth. In this process termed "cancer immunoediting," cancer clones evolve to avoid immune-medi- The immune system is a critical regulator of tumor biology with ated elimination by leukocytes that have antitumor properties the capacity to support or inhibit tumor development, growth, (6). However, some tumors may also escape elimination by invasion, and metastasis. Strategies designed to harness the recruiting immunosuppressive leukocytes, which orchestrate a immune system are the focus of several recent promising thera- microenvironment that spoils the productivity of an antitumor peutic approaches for patients with cancer. For example, adoptive immune response (7). Thus, although the immune system can be T-cell therapy has produced impressive remissions in patients harnessed, in some cases, for its antitumor potential, clinically with advanced malignancies (1). In addition, therapeutic mono- relevant tumors appear to be marked by an immune system that clonal antibodies designed to disrupt inhibitory signals received actively selects for poorly immunogenic tumor clones and/or by T cells through the cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated antigen establishes a microenvironment that suppresses productive anti- 4 (CTLA-4; also known as CD152) and programmed cell death-1 tumor immunity (Fig. -

Dermatopathology

76A ANNUAL MEETING ABSTRACTS of the nodules aspirated was 1.8 (NNAN), 3.2 (HA), 3.0 (HCa) and 2.9 (PTC). The average numbers of nodules identified by US were 3.3 in NNAN, 2.0 in HA, 1.7 in HCa, Dermatopathology and 1.8 in PTC (p<0.05). Furthermore, 40% (4 of 10) and 20% (2 of 10) of HCa were vascularized and microcalcified on US, respectively; and 50% (7 of 14) of NNAN had 337 CD10 and Ep-CAM Expression in Basal Cell Carcinoma, Classical multiple (5) small nodules in the background thyroid. FNA Findings – the Hurthle cell Trichoepithelioma, and Desmoplastic Trichoepithelioma tumors had more cellular smears, discohesive Hurthle cells, few, if any, lymphocytes, TE Abbott, MD Cole, JW Patterson, MR Wick. University of Virginia Health System, and scarce or absent colloid in comparison to the smears from NNAN. Charlottesville, VA. Conclusions: Dominant thyroid nodules 2 cm or less on US without evidence of Background: The distinction between basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and increased vascularity or microcalcifications in combination with the background trichoepithelioma (TE) has historically been made on the basis of specific histologic thyroid containing multiple (3 or more) smaller nodules and the FNA smears containing criteria, but it may be difficult when the tumor sample is limited. Recent reports have some lymphoid aggregates with Hurthle cells in moderately sized sheets are likely to suggested a utility for CD10 and Ep-CAM immunostaining in recognizing BCC. be benign. Communication between clinician and pathologist correlating US and FNA Accordingly, this study was initiated in order to determine whether those markers findings in difficult cases may avoid unnecessary surgery. -

Tumor Immunology 101 for the Non-Immunologist

Tumor Immunology 101 For the Non-Immunologist Louis M. Weiner, MD Director, Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center Francis L. and Charlotte G. Gragnani Chair Professor and Chairman, Department of Oncology Georgetown University Medical Center Disclosure Consulting Fees Ownership Interest Abbvie Pharmaceuticals Celldex Novartis Jounce Merck Merrimack Genetech Symphogen Cytomax Immunovative Therapies, Ltd. Contracted Research Symphogen We Have Been at War Against Cancer Throughout Human History Tumor President Nixon declares a “War on Cancer” in 1971 Medieval Saxon man with a large tumor of the left femur Which Target? Hanahan, Weinberg, Cell 2000 The “War on Cancer” is fought one person at a time… • Primary Combatants: – Malignant cell population – Host immune system • The host immune system is the dominant active enemy faced by a developing cancer • All “successful” cancers must solve the challenges of overcoming defenses erected by host immune systems Which System? Hanahan, Weinberg, Cell 2011 The Case for Cancer Immunotherapy • Surprisingly few new truly curative anti- cancer cytotoxic drugs or targeted therapies in 20+ years – Tumor heterogeneity – Too many escape routes? • The immune response is designed to identify and disable “escape routes ” that cancers employ • Immunotherapy can cure cancers Immunotherapy • Treatment of disease by inducing, enhancing, or suppressing an immune response • “Treating the immune system so it can treat the cancer” (J. Wolchok) Some Examples of Successful Cancer Immunotherapy • Type 1 interferons – bladder -

Serum Alpha-Fetoprotein Values in Dogs with Various Hepatic Diseases

Serum alpha-fetoprotein Values in Dogs with Various Hepatic Diseases Takatsugu YAMADA,1,2), Megumi FUJITA1), Satoshi KITAO3), Yoshinori ASHIDA1), Kazuya NISHIZONO1), Ryo TSUCHIYA1), Takuo SHIDA4), and Kousaku KOBAYASHI1) 1)Laboratory of Veterinary Internal Medicine and 4)Laboratory of Veterinary Radiology, School of Veterinary Medicine; 2)Research Institute of Bioscience, Azabu University, 1–17–71 Fuchinobe, Sagamihara, Kanagawa, 229–8501 and 3)Doubutsu Medical Center, 1–6–45 Nakahozumi, Ibaraki-shi, Osaka 567–0034, Japan (Received 2 December 1997/Accepted 10 February 1999) ABSTRACT. Serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) values were measured in hepatic diseased dogs with or without tumor and non-hepatic tumor bearing dogs by a sandwich ELISA using anti-dog AFP antiserum. Serum AFP values were less than 70 ng/ml in clinically healthy dogs. The values in dogs with hepatocellular carcinoma were higher than 1,400 ng/ml in 7 of 9 dogs, wherever those in two dogs with cholangiocarcinoma were in the normal range. Serum AFP values in hepatic diseased dogs without tumor were also high, however, the values were below 500 ng/ml in 90% of the dogs. In non-hepatic tumor dogs, serum AFP values were less than 500 ng/ml in 76% of the dogs. In the surgically removal cases with hepatocellular carcinoma, serum AFP values rapidly decreased. These results suggested that the sandwich ELISA using anti-dog AFP antiserum was an available method for diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma in dogs.—KEY WORDS: alpha-fetoprotein, canine, ELISA, tumor. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 61(6): 657–659, 1999 Serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) values have been used with hepatocellular carcinoma were also monitored AFP for the diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma [4, 5–6, 14] values after surgical removal of masses. -

Monoclonal Antibodies in Cancer Therapy

Clin Oncol Cancer Res (2011) 8: 215–219 215 DOI 10.1007/s11805-011-0583-7 Monoclonal Antibodies in Cancer Therapy Yu-Ting GUO1,2 ABSTRACT Monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) are a relatively new Qin-Yu HOU1,2 innovation in cancer treatment. At present, some monoclonal antibodies have increased the efficacy of the treatment of certain 1,2 Nan WANG tumors with acceptable safety profiles. When monoclonal antibodies enter the body and attach to cancer cells, they function in several different ways: first, they can trigger the immune system to attack and kill that cancer cell; second, they can block the growth signals; third, they can prevent the formation of new blood vessels. Some naked 1 Key Laboratory of Industrial Fermentation MAbs such as rituximab can be directed to attach to the surface of Microbiology, Ministry of Education, Tianjin, cancer cells and make them easier for the immune system to find and 300457, China. destroy. The ability to produce antibodies with limited immunogeni- 2 Tianjin Key Laboratory of Industrial Micro- city has led to the production and testing of a host of agents, several biology, College of Biotechnology, Tianjin of which have demonstrated clinically important antitumor activity University of Science and Technology, Tianjin, 300457, China. and have received U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA) approval as cancer treatments. To reduce the immunogenicity of murine anti- bodies, murine molecules are engineered to remove the immuno- genic content and to increase their immunologic efficiency. Radiolabeled antibodies composed of antibodies conjugated to radionuclides show efficacy in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Anti- vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) antibodies such as bevacizumab intercept the VEGF signal of tumors, thereby stopping them from connecting with their targets and blocking tumor growth. -

Dermoscopic Features of Skin Lesions in Patients with Mastocytosis

STUDY Dermoscopic Features of Skin Lesions in Patients With Mastocytosis Sergio Vano-Galvan, MD, PhD; Iva´n A´ lvarez-Twose, MD; Elena De las Heras, MD, PhD; J. M. Morgado, Msc; Almudena Matito, MD; Laura Sa´nchez-Mun˜oz, MD, PhD; Maria N. Plana, MD, PhD; Pedro Jae´n, MD, PhD; Alberto Orfao, MD, PhD; Luis Escribano, MD, PhD Objectives: To evaluate dermoscopic features in a group factors for more symptomatic forms of the disease ac- of 127 patients with mastocytosis in the skin and to in- cording to the need for daily antimediator therapy. vestigate the relationship between different dermo- scopic patterns and other clinical and biological charac- Results: Four distinct dermoscopic patterns were ob- teristics of the disease. served: yellow-orange blot, pigment network, reticular vascular pattern, and (most frequently) light-brown blot. Design: Clinical and laboratory data were compared A reticular vascular pattern was identified in all telangi- among patients with mastocytosis grouped according to ectasia macular eruptiva and some maculopapular mas- the different dermoscopic patterns. tocytosis. In turn, all patients with mastocytoma dis- played the yellow-orange blot pattern. The reticular Setting: Patients were selected from the Instituto de Es- vascular dermoscopic pattern was associated with the need tudios de Mastocitosis de Castilla La Mancha and the De- for daily antimediator therapy; this pattern, together with partment of Dermatology of Hospital Universitario Ramo´n serum tryptase levels and plaque-type mastocytosis, rep- y Cajal from April 1 through September 30, 2009. resented the best combination of independent factors to predict the need for maintained antimediator therapy.