Assemblers, Linkers, and Loaders

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction to Computer Systems 15-213/18-243, Spring 2009 1St

M4-L3: Executables CSE351, Winter 2021 Executables CSE 351 Winter 2021 Instructor: Teaching Assistants: Mark Wyse Kyrie Dowling Catherine Guevara Ian Hsiao Jim Limprasert Armin Magness Allie Pfleger Cosmo Wang Ronald Widjaja http://xkcd.com/1790/ M4-L3: Executables CSE351, Winter 2021 Administrivia ❖ Lab 2 due Monday (2/8) ❖ hw12 due Friday ❖ hw13 due next Wednesday (2/10) ▪ Based on the next two lectures, longer than normal ❖ Remember: HW and readings due before lecture, at 11am PST on due date 2 M4-L3: Executables CSE351, Winter 2021 Roadmap C: Java: Memory & data car *c = malloc(sizeof(car)); Car c = new Car(); Integers & floats c->miles = 100; c.setMiles(100); x86 assembly c->gals = 17; c.setGals(17); Procedures & stacks float mpg = get_mpg(c); float mpg = Executables free(c); c.getMPG(); Arrays & structs Memory & caches Assembly get_mpg: Processes pushq %rbp language: movq %rsp, %rbp Virtual memory ... Memory allocation popq %rbp Java vs. C ret OS: Machine 0111010000011000 100011010000010000000010 code: 1000100111000010 110000011111101000011111 Computer system: 3 M4-L3: Executables CSE351, Winter 2021 Reading Review ❖ Terminology: ▪ CALL: compiler, assembler, linker, loader ▪ Object file: symbol table, relocation table ▪ Disassembly ▪ Multidimensional arrays, row-major ordering ▪ Multilevel arrays ❖ Questions from the Reading? ▪ also post to Ed post! 4 M4-L3: Executables CSE351, Winter 2021 Building an Executable from a C File ❖ Code in files p1.c p2.c ❖ Compile with command: gcc -Og p1.c p2.c -o p ▪ Put resulting machine code in -

CERES Software Bulletin 95-12

CERES Software Bulletin 95-12 Fortran 90 Linking Experiences, September 5, 1995 1.0 Purpose: To disseminate experience gained in the process of linking Fortran 90 software with library routines compiled under Fortran 77 compiler. 2.0 Originator: Lyle Ziegelmiller ([email protected]) 3.0 Description: One of the summer students, Julia Barsie, was working with a plot program which was written in f77. This program called routines from a graphics package known as NCAR, which is also written in f77. Everything was fine. The plot program was converted to f90, and a new version of the NCAR graphical package was released, which was written in f77. A problem arose when trying to link the new f90 version of the plot program with the new f77 release of NCAR; many undefined references were reported by the linker. This bulletin is intended to convey what was learned in the effort to accomplish this linking. The first step I took was to issue the "-dryrun" directive to the f77 compiler when using it to compile the original f77 plot program and the original NCAR graphics library. "- dryrun" causes the linker to produce an output detailing all the various libraries that it links with. Note that these libaries are in addition to the libaries you would select on the command line. For example, you might compile a program with erbelib, but the linker would have to link with librarie(s) that contain the definitions of sine or cosine. Anyway, it was my hypothesis that if everything compiled and linked with f77, then all the libraries must be contained in the output from the f77's "-dryrun" command. -

Linking + Libraries

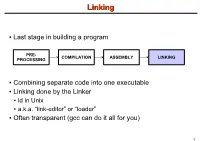

LinkingLinking ● Last stage in building a program PRE- COMPILATION ASSEMBLY LINKING PROCESSING ● Combining separate code into one executable ● Linking done by the Linker ● ld in Unix ● a.k.a. “link-editor” or “loader” ● Often transparent (gcc can do it all for you) 1 LinkingLinking involves...involves... ● Combining several object modules (the .o files corresponding to .c files) into one file ● Resolving external references to variables and functions ● Producing an executable file (if no errors) file1.c file1.o file2.c gcc file2.o Linker Executable fileN.c fileN.o Header files External references 2 LinkingLinking withwith ExternalExternal ReferencesReferences file1.c file2.c int count; #include <stdio.h> void display(void); Compiler extern int count; int main(void) void display(void) { file1.o file2.o { count = 10; with placeholders printf(“%d”,count); display(); } return 0; Linker } ● file1.o has placeholder for display() ● file2.o has placeholder for count ● object modules are relocatable ● addresses are relative offsets from top of file 3 LibrariesLibraries ● Definition: ● a file containing functions that can be referenced externally by a C program ● Purpose: ● easy access to functions used repeatedly ● promote code modularity and re-use ● reduce source and executable file size 4 LibrariesLibraries ● Static (Archive) ● libname.a on Unix; name.lib on DOS/Windows ● Only modules with referenced code linked when compiling ● unlike .o files ● Linker copies function from library into executable file ● Update to library requires recompiling program 5 LibrariesLibraries ● Dynamic (Shared Object or Dynamic Link Library) ● libname.so on Unix; name.dll on DOS/Windows ● Referenced code not copied into executable ● Loaded in memory at run time ● Smaller executable size ● Can update library without recompiling program ● Drawback: slightly slower program startup 6 LibrariesLibraries ● Linking a static library libpepsi.a /* crave source file */ … gcc .. -

Using the DLFM Package on the Cray XE6 System

Using the DLFM Package on the Cray XE6 System Mike Davis, Cray Inc. Version 1.4 - October 2013 1.0: Introduction The DLFM package is a set of libraries and tools that can be applied to a dynamically-linked application, or an application that uses Python, to provide improved performance during the loading of dynamic libraries and importing of Python modules when running the application at large scale. Included in the DLFM package are: a set of wrapper functions that interface with the dynamic linker (ld.so) to cache the application's dynamic library load operations; and a custom libpython.so, with a set of optimized components, that caches the application's Python import operations. 2.0: Dynamic Linking and Python Importing Without DLFM When a dynamically-linked application is executed, the set of dependent libraries is loaded in sequence by ld.so prior to the transfer of control to the application's main function. This set of dependent libraries ordinarily numbers a dozen or so, but can number many more, depending on the needs of the application; their names and paths are given by the ldd(1) command. As ld.so processes each dependent library, it executes a series of system calls to find the library and make the library's contents available to the application. These include: fd = open (/path/to/dependent/library, O_RDONLY); read (fd, elfhdr, 832); // to get the library ELF header fstat (fd, &stbuf); // to get library attributes, such as size mmap (buf, length, prot, MAP_PRIVATE, fd, offset); // read text segment mmap (buf, length, prot, MAP_PRIVATE, fd, offset); // read data segment close (fd); The number of open() calls can be many times larger than the number of dependent libraries, because ld.so must search for each dependent library in multiple locations, as described on the ld.so(1) man page. -

Environment Variable and Set-UID Program Lab 1

SEED Labs – Environment Variable and Set-UID Program Lab 1 Environment Variable and Set-UID Program Lab Copyright © 2006 - 2016 Wenliang Du, All rights reserved. Free to use for non-commercial educational purposes. Commercial uses of the materials are prohibited. The SEED project was funded by multiple grants from the US National Science Foundation. 1 Overview The learning objective of this lab is for students to understand how environment variables affect program and system behaviors. Environment variables are a set of dynamic named values that can affect the way running processes will behave on a computer. They are used by most operating systems, since they were introduced to Unix in 1979. Although environment variables affect program behaviors, how they achieve that is not well understood by many programmers. As a result, if a program uses environment variables, but the programmer does not know that they are used, the program may have vulnerabilities. In this lab, students will understand how environment variables work, how they are propagated from parent process to child, and how they affect system/program behaviors. We are particularly interested in how environment variables affect the behavior of Set-UID programs, which are usually privileged programs. This lab covers the following topics: • Environment variables • Set-UID programs • Securely invoke external programs • Capability leaking • Dynamic loader/linker Readings and videos. Detailed coverage of the Set-UID mechanism, environment variables, and their related security problems can be found in the following: • Chapters 1 and 2 of the SEED Book, Computer & Internet Security: A Hands-on Approach, 2nd Edition, by Wenliang Du. -

Chapter 6: the Linker

6. The Linker 6-1 Chapter 6: The Linker References: • Brian W. Kernighan / Dennis M. Ritchie: The C Programming Language, 2nd Ed. Prentice-Hall, 1988. • Samuel P. Harbison / Guy L. Steele Jr.: C — A Reference Manual, 4th Ed. Prentice-Hall, 1995. • Online Documentation of Microsoft Visual C++ 6.0 (Standard Edition): MSDN Library: Visual Studio 6.0 release. • Horst Wettstein: Assemblierer und Binder (in German). Carl Hanser Verlag, 1979. • Peter Rechenberg, Gustav Pomberger (Eds.): Informatik-Handbuch (in German). Carl Hanser Verlag, 1997. Kapitel 12: Systemsoftware (H. M¨ossenb¨ock). Stefan Brass: Computer Science III Universit¨atGiessen, 2001 6. The Linker 6-2 Overview ' $ 1. Introduction (Overview) & % 2. Object Files, Libraries, and the Linker 3. Make 4. Dynamic Linking Stefan Brass: Computer Science III Universit¨atGiessen, 2001 6. The Linker 6-3 Introduction (1) • Often, a program consists of several modules which are separately compiled. Reasons are: The program is large. Even with fast computers, editing and compiling a single file with a million lines leads to unnecessary delays. The program is developed by several people. Different programmers cannot easily edit the same file at the same time. (There is software for collaborative work that permits that, but it is still a research topic.) A large program is easier to understand if it is divided into natural units. E.g. each module defines one data type with its operations. Stefan Brass: Computer Science III Universit¨atGiessen, 2001 6. The Linker 6-4 Introduction (2) • Reasons for splitting a program into several source files (continued): The same module might be used in different pro- grams (e.g. -

GNU GCC Compiler

C-Refresher: Session 01 GNU GCC Compiler Arif Butt Summer 2017 I am Thankful to my student Muhammad Zubair [email protected] for preparation of these slides in accordance with my video lectures at http://www.arifbutt.me/category/c-behind-the-curtain/ Today’s Agenda • Brief Concept of GNU gcc Compiler • Compilation Cycle of C-Programs • Contents of Object File • Multi-File Programs • Linking Process • Libraries Muhammad Arif Butt (PUCIT) 2 Compiler Compiler is a program that transforms the source code of a high level language into underlying machine code. Underlying machine can be x86 sparse, Linux, Motorola. Types of Compilers: gcc, clang, turbo C-compiler, visual C++… Muhammad Arif Butt (PUCIT) 3 GNU GCC Compiler • GNU is an integrated distribution of compilers for C, C++, OBJC, OBJC++, JAVA, FORTRAN • gcc can be used for cross compile Cross Compile: • Cross compile means to generate machine code for the platform other than the one in which it is running • gcc uses tools like autoConf, automake and lib to generate codes for some other architecture Muhammad Arif Butt (PUCIT) 4 Compilation Process Four stages of compilation: •Preprocessor •Compiler •Assembler •Linker Muhammad Arif Butt (PUCIT) 5 Compilation Process(cont...) hello.c gcc –E hello.c 1>hello.i Preprocessor hello.i 1. Preprocessor • Interpret Preprocessor Compiler directives • Include header files • Remove comments • Expand headers Assembler Linker Muhammad Arif Butt (PUCIT) 6 Compilation Process(cont...) hello.c 2. Compiler • Check for syntax errors Preprocessor • If no syntax error, the expanded code is converted to hello.i assembly code which is understood by the underlying Compiler gcc –S hello.i processor, e.g. -

An-572 Application Note

AN-572 a APPLICATION NOTE One Technology Way • P.O. Box 9106 • Norwood, MA 02062-9106 • 781/329-4700 • World Wide Web Site: http://www.analog.com Overlay Linking on the ADSP-219x By David Starr OVERVIEW the linker. Having a number of memories to deal with This applications note is for software designers starting makes the DSP linker somewhat more complex than an ADSP-219x overlay design. Using this note and the linkers for Princeton architecture machines. information in the Linker and Utilities Manual for ADSP- In addition, each DSP project must fit into a different 21xx Family DSPs the following may be done: memory arrangement. Different DSP boards have differ- Divide a program into overlays. ent amounts of memory, located at different addresses. Write LDF files for simple and overlay links. The ADSP-219x family supports an external memory Write an overlay manager. interface, allowing rather large amounts of memory, but at a penalty in speed. Internal memory is ten times faster HARVARD VS. PRINCETON ARCHITECTURE AND THE than external memory, so it may be desirable to keep LINKER large amounts of program code in external memory Early in the history of computing, the modern design of swap parts of it to internal memory for speed in execu- one memory to hold both data and program instructions tion. Such a program is said to run in “overlays.” acquired the name “Princeton.” Such a machine is flex- For code reuse and portability, a program should not ible because programs with lots of code and little data require modification to run in different machines or in work, as well as programs with little code and lots of different locations in memory. -

An Efficient Protocol for Linker Scanning Mutagenesis: Analysis of the Translational Regulation of an Escherichia Coli RNA Polymerase Subunit Gene Derek M

1997 Oxford University Press Nucleic Acids Research, 1997, Vol. 25, No. 21 4209–4218 An efficient protocol for linker scanning mutagenesis: analysis of the translational regulation of an Escherichia coli RNA polymerase subunit gene Derek M. Dykxhoorn, Rebecca St. Pierre, Oded Van Ham and Thomas Linn* Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario N6A 5C1, Canada Received August 18, 1997; Accepted September 12, 1997 ABSTRACT of the synthetic linker. Though effective, this approach involves a number of time consuming steps. Many deletions have to be A protocol has been developed that is capable of generated and sequenced before appropriate 5′ and 3′ combinations saturating regions hundreds of basepairs in length can be identified, followed by a separate ligation for each 5′/3′ pair with linker scanning mutations. The efficacy of this to produce the final linker scanning mutation. method stems from the design of the linker scanning We have developed a more efficient protocol for linker scanning mutagenesis (LSM) cassette which is composed of a mutagenesis that is capable of generating a library consisting of selectable marker flanked by two oligonucleotides, hundreds of mutations. This protocol makes use of a linker scanning each of which contains a recognition site for a different mutagenesis (LSM) cassette which is composed of two synthetic restriction endonuclease. The cleavage site for one oligonucleotides surrounding the selectable tetracycline resistance endonuclease is within its recognition site, while the gene. The oligonucleotide on one side of the tetracycline resistance second endonuclease cleaves in the target DNA gene has the recognition site for SmaI, while the other beyond the end of the cassette. -

Linking Basics.Docx Page 1 of 35 Initial Creation: March, 24, 2015 Date Updated: October 4, 2015

An Overview of Object Files And Linking Harry H. Porter III Portland State University cs.pdx.edu/~harry April 9, 2015 Goals of this Paper Audience: CS-201 students Coverage: Compiling Linking Object files External Symbols Relocatable Code Segments (.text, .data., .bss) Filename: Linking Basics.docx Page 1 of 35 Initial Creation: March, 24, 2015 Date Updated: October 4, 2015 Overview In order to create an executable file, a program must be compiled and linked. In this paper, I’ll use the “C” programming language as an example, but this discussion applies to other compiled languages like C++. Languages that are interpreted (like Java or Python) do things differently and linking does not apply to them. We’ll also discuss the Linux/Unix system, but other OSes are similar. A program begins as a human readable source text file, such as “hello.c”. The program must first be compiled and this step produces a human readable text file in assembly code. Then the assembly code version is assembled and this produces an object file. Finally, the object file is linked and the executable file is produced. At some later time, the OS will load the executable file into memory run it. Many programs are large and these programs are broken into several “.c” files. We’ll look at an example involving two files, “hello.c” and “there.c”. Each of the .c files must be compiled and assembled, but these steps can be done independently. In other words, we can compile and assemble hello.c before we even create the there.c file. -

Linker Script Guide Emprog

Linker Script Guide Emprog Emprog ThunderBench™ Linker Script Guide Version 1.2 ©May 2013 Page | 1 Linker Script Guide Emprog 1 - Linker Script guide 2 -Arm Specific Options Page | 2 Linker Script Guide Emprog 1 The Linker Scripts Every link is controlled by a linker script. This script is written in the linker command language. The main purpose of the linker script is to describe how the sections in the input files should be mapped into the output file, and to control the memory layout of the output file. Most linker scripts do nothing more than this. However, when necessary, the linker script can also direct the linker to perform many other operations, using the commands described below. The linker always uses a linker script. If you do not supply one yourself, the linker will use a default script that is compiled into the linker executable. You can use the ‘--verbose’ command line option to display the default linker script. Certain command line options, such as ‘-r’ or ‘-N’, will affect the default linker script. You may supply your own linker script by using the ‘-T’ command line option. When you do this, your linker script will replace the default linker script. You may also use linker scripts implicitly by naming them as input files to the linker, as though they were files to be linked. 1.1 Basic Linker Script Concepts We need to define some basic concepts and vocabulary in order to describe the linker script language. The linker combines input files into a single output file. The output file and each input file are in a special data format known as an object file format. -

Introduction to Computer Systems 15-213/18-243, Spring 2009

Carnegie Mellon Linking 15-213: Introduction to Computer Systems 13th Lecture, February 23rd, 2016 Instructors: Franz Franchetti & Seth Copen Goldstein, Ralf Brown, and Brian Railing Bryant and O’Hallaron, Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective, Third Edition 1 Carnegie Mellon Today Linking Case study: Library interpositioning Bryant and O’Hallaron, Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective, Third Edition 2 Carnegie Mellon Example C Program int sum(int *a, int n); int sum(int *a, int n) { int array[2] = {1, 2}; int i, s = 0; int main() for (i = 0; i < n; i++) { { s += a[i]; int val = sum(array, 2); } return val; return s; } } main.c sum.c Bryant and O’Hallaron, Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective, Third Edition 3 Carnegie Mellon Static Linking Programs are translated and linked using a compiler driver: . linux> gcc -Og -o prog main.c sum.c . linux> ./prog main.c sum.c Source files Translators Translators (cpp, cc1, as) (cpp, cc1, as) main.o sum.o Separately compiled relocatable object files Linker (ld) Fully linked executable object file prog (contains code and data for all functions defined in main.c and sum.c) Bryant and O’Hallaron, Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective, Third Edition 4 Carnegie Mellon Why Linkers? Reason 1: Modularity . Program can be written as a collection of smaller source files, rather than one monolithic mass. Can build libraries of common functions (more on this later) . e.g., Math library, standard C library Bryant and O’Hallaron, Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective, Third Edition 5 Carnegie Mellon Why Linkers? (cont) Reason 2: Efficiency .