SCMA Distinguished Speaker Series 2014 10 November 2014 Maxwell Chambers MAKING WAVES in ARBITRATION – the SINGAPORE EXPERIENCE Justice Steven Chong

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

7. Civil Procedure

(2008) 9 SAL Ann Rev Civil Procedure 143 7. CIVIL PROCEDURE Cavinder BULL SC MA (Oxford), LLM (Harvard); Barrister (Gray’s Inn), Attorney-at-Law (New York State); Advocate and Solicitor (Singapore). Jeffrey PINSLER SC LLB (Liverpool), LLM (Cambridge), LLD (Liverpool); Barrister (Middle Temple), Advocate and Solicitor (Singapore); Professor, Faculty of Law, National University of Singapore. Appeals Leave to appeal 7.1 In Blenwel Agencies Pte Ltd v Tan Lee King [2008] 2 SLR 529, the Court of Appeal held that where the High Court has refused leave to appeal against a decision of the District Court, there can be no further recourse after the High Court has adjudicated on the matter. This case was an extension of the Court of Appeal’s previous judgment in SBS Transit Ltd v Koh Swee Ann [2004] 3 SLR 365, which concerned an application for leave to appeal against the decision of a Magistrate’s Court. 7.2 Andrew Phang JA reiterated the fundamental principle that where a legal decision cannot be appealed against as of right but requires express permission from a named authority before it can be appealed against, the decision of that authority as to whether or not to grant leave to appeal is final (Blenwel Agencies Pte Ltd v Tan Lee King [2008] 2 SLR 529 at [14]). It is clear from s 21(1) of the Supreme Court of Judicature Act (Cap 322, 2007 Rev Ed) that the High Court is the authority with the final say as to whether to grant or refuse leave to appeal against a decision of the Subordinate Courts. -

Minlaw) Invited Applications for the Second Round of Qualifying Foreign Law Practice (QFLP) Licences on 1 July 2012

PRESS RELEASE AWARD OF THE SECOND ROUND OF QUALIFYING FOREIGN LAW PRACTICE LICENCES The Ministry of Law (MinLaw) invited applications for the second round of Qualifying Foreign Law Practice (QFLP) licences on 1 July 2012. Twenty-three applications were received by the closing date of 31 August 2012. 2 QFLP licences will be awarded to the following four firms (listed in alphabetical order): Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher; Jones Day; Linklaters, and Sidley Austin. 3 The firms will have up to six months from 1 April 2013 to commence their operations as QFLPs, and their licences will be valid for an initial period of five years from the respective start dates. Background 4 The QFLP scheme was introduced in 2008 following the recommendations of the Committee to Develop the Legal Sector chaired by Justice V K Rajah. The Committee, which included senior lawyers from top local firms, assessed that local firms and local lawyers would benefit from the increased foreign presence and competition over time. 5 The QFLP licences allow Foreign Law Practices (FLPs) to practise in permitted areas of Singapore law1. The scheme seeks to support the growth of key economic sectors, grow the legal sector, as well as to offer additional 1 Permitted areas are all areas except domestic areas of litigation and general practice, for example, criminal law, retail conveyancing, family law and administrative law. The QFLPs can practise the permitted areas through Singapore-qualified lawyers with practising certificates or foreign lawyers holding the foreign practitioner certificate. 1 opportunities for our lawyers. A total of six FLPs2 were awarded QFLP licences in the first round in 2008. -

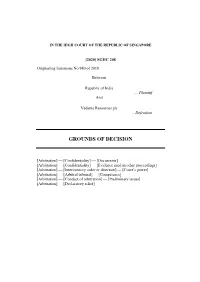

Grounds of Decision

IN THE HIGH COURT OF THE REPUBLIC OF SINGAPORE [2020] SGHC 208 Originating Summons No 980 of 2018 Between Republic of India … Plaintiff And Vedanta Resources plc … Defendant GROUNDS OF DECISION [Arbitration] — [Confidentiality] — [Documents] [Arbitration] — [Confidentiality] — [Evidence used in other proceedings] [Arbitration] — [Interlocutory order or direction] — [Court’s power] [Arbitration] — [Arbitral tribunal] — [Competence] [Arbitration] — [Conduct of arbitration] — [Preliminary issues] [Arbitration] — [Declaratory relief] TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION............................................................................................1 BACKGROUND FACTS ................................................................................4 THE CAIRN GROUP RESTRUCTURING...............................................................4 INDIA ISSUES ASSESSMENT ORDERS.................................................................4 COMMENCEMENT OF THE ARBITRATIONS ........................................................5 THE ARBITRAL TRIBUNALS ISSUE PROCEDURAL ORDERS ................................6 Cairn Arbitration Procedural Order No. 10..............................................7 Vedanta Arbitration Procedural Order No. 3............................................9 Vedanta Arbitration Procedural Order No. 6..........................................10 Vedanta Arbitration Procedural Order No. 7..........................................11 THE PRELIMINARY QUESTION .............................................................12 -

Dinner Hosted by the Judiciary for the Forum of Senior Counsel

DINNER HOSTED BY THE JUDICIARY FOR THE FORUM OF SENIOR COUNSEL FRIDAY, 14 MAY 2010 REMARKS BY CHIEF JUSTICE CHAN SEK KEONG Ladies and Gentlemen: My colleagues and I warmly welcome you to tonight’s dinner, the second that the Judiciary is hosting for the Forum of Senior Counsel. In particular, I would welcome my predecessor as AG, Mr Tan Boon Teik who, instead of relaxing at home, has taken the trouble to join us tonight. The presence of so many Judges of the Supreme Court and Senior Counsel augurs well for this annual series of dinners evolving into a tradition that will continue to strengthen the bonds between the Bar and the Judiciary. 2. This dinner is not meant to be an occasion for long boring speeches, so I will keep my remarks short and make only three points. First, the Institute of Legal Education is in the process of developing a framework for Continuing Professional Development (CPD) in Singapore. Justice V K Rajah and his committee have been working very hard to set up a CPD programme that will be effective and meaningful to the Bar. It will be a serious programme, under which we will drag unwilling horses to the trough to drink. But we hope that the CPD programme will provide a true learning experience and not be a wasteful imposition on the Bar. It will be a great achievement if members of the Bar welcome this programme and not dismiss it as being a PR exercise. 2 3. When the CPD programme is finalised, we will need Senior Counsel and leading members of the corporate Bar to become lecturers, instructors and mentors. -

Rankine Bernadette Adeline V Chenet Finance

Rankine Bernadette Adeline v Chenet Finance Ltd [2011] SGHC 79 Case Number : Suit No 971 of 2009 (Registrar's Appeal No.122 of 2010) Decision Date : 31 March 2011 Tribunal/Court : High Court Coram : Kan Ting Chiu J Counsel Name(s) : Cavinder Bull SC and Gerui Lim (Instructed) (Drew & Napier LLC), and Dawn Tan (Eldan Law LLP) for the Plaintiff; N Sreenivasan and K Gopalan (Straits Law Practice) for the Defendant. Parties : Rankine Bernadette Adeline — Chenet Finance Ltd CIVIL PROCEDURE – summary judgment 31 March 2011 Kan Ting Chiu J: 1 In this action, the Defendant, Chenet Finance Limited, was given conditional leave to defend the claim of the Plaintiff, Rankine Bernadette Adeline. The Defendant has appealed against my order. In the meantime, final judgment has been entered after the Defendant failed to comply with the condition imposed. The claim 2 The Plaintiff was a holder of 1,000,000 shares of a company Berlian Ferries Pte Ltd (“Berlian”) in May 2004. The Plaintiff discovered that those shares in Berlian (“the shares”) had purportedly been sold by her with consideration paid to her, and that the Defendant was the purchaser of the shares. As the Plaintiff had not agreed to sell the shares to the Defendant and had not received any consideration from the Defendant, she sought from Berlian copies of any transfer of shares signed by her. Berlian in turn informed the Defendant that it (Berlian) did not have the transfer forms relating to the shares. Berlian also informed the Defendant that as the Defendant’s representatives had inspected and made copies from the secretarial files of Berlian, the Defendant should reply to the Plaintiff, but the Defendant had not supplied copies of the transfer forms to the Plaintiff. -

Engaging New Media: Challenging Old Assumptions, Is Our First

// ENGAGING NEW MEDIA / / CHALLENGING OLD ASSUMPTIONS A report by the Advisory Council on the Impact of New Media on Society (AIMS) December 2008 // ENGAGING NEW MEDIA / / CHALLENGING OLD ASSUMPTIONS A report by the Advisory Council on the Impact of New Media on Society Singapore December 2008 Published December 2008 ISSN 1793-8961 © Advisory Council on the Impact of New Media on Society All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanised, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission of the copyright holder. TABLE OF CONTENTS p 2—3 // Foreword / p 5—9 // Introduction / p 11—25 // Executive Summary / p 27—49 Chapter 1 // E-Engagement / / Trends in New Media / Why Engage Online? / Embarking on E-Engagement / E-Participation / Barriers to E-Engagement / Reasons for E-Engagement / Risk Assessment / Public Feedback / Recommendations Following Public Feedback / Conclusion p 51—78 Chapter 2 // Online Political Content / / Background / Review of Light-touch Policy / Online Election Advertising in Other Countries / Proposed Recommendations in the Consultation Paper / Public Feedback / Recommendations Following Public Feedback / Conclusion p 80—107 Chapter 3 // Protection of Minors / / Risks to Minors / How are these Risks Managed? / The Key Lies in Education / What is Being Done in Singapore / Proposed Recommendations in the Consultation Paper / Public Feedback / AIMS' Views / Recommendations Following Public Feedback -

7. Civil Procedure

(2007) 8 SAL Ann Rev Civil Procedure 99 7. CIVIL PROCEDURE Cavinder BULL SC MA (Oxford), LLM (Harvard); Barrister (Gray’s Inn), Attorney-at-Law (New York State); Advocate and Solicitor (Singapore). Jeffrey PINSLER SC LLB (Liverpool), LLM (Cambridge), LLD (Liverpool); Barrister (Middle Temple), Advocate and Solicitor (Singapore); Professor, Faculty of Law, National University of Singapore. Accounts 7.1 Where a party renders accounts in compliance with the terms of a judgment, it is not appropriate for the opposing party (who contests the accounting period relied upon) to make an application by summons for the purpose of determining the correct accounting period. This is a matter which must be left to the determination of the registrar at the inquiry into those accounts. Such an application was made pursuant to a consent judgment in Seiko Epson Corp v Sepoms Technology Pte Ltd [2007] 3 SLR 225. The High Court considered O 43 r 3 of the Rules of Court (Cap 322, R 5, 2006 Rev Ed) in conjunction with O 38 r 8 and concluded that an application for an interlocutory hearing by summons was misconceived (at [14]–[15]). Appeals Court’s discretion to waive security deposit 7.2 In Lee Hsien Loong v Singapore Democratic Party [2008] 1 SLR 757, the Court of Appeal held that the provision for security deposit stipulated in O 57 r 3(3) is mandatory and therefore cannot be waived by the court. 7.3 Waiving the provision for security deposit, even for a bankrupt, would effectively allow the applicant a right of appeal free from any need to compensate the plaintiffs if his appeal fails. -

![Ng Chee Weng V Lim Jit Ming Bryan and Another [2011] SGHC 120 Case Number : Suit No](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5438/ng-chee-weng-v-lim-jit-ming-bryan-and-another-2011-sghc-120-case-number-suit-no-3655438.webp)

Ng Chee Weng V Lim Jit Ming Bryan and Another [2011] SGHC 120 Case Number : Suit No

Ng Chee Weng v Lim Jit Ming Bryan and another [2011] SGHC 120 Case Number : Suit No. 453 of 2009/F (Registrar's Appeal No.379 of 2010/D) Decision Date : 16 May 2011 Tribunal/Court : High Court Coram : Kan Ting Chiu J Counsel Name(s) : Tan Cheng Han SC (instructed) and Vijay Kumar (Vijay & Co) for the Plaintiff; Cavinder Bull SC, Woo Shu Yan and Lin Shumin (Drew & Napier LLC) for the Defendants. Parties : Ng Chee Weng — Lim Jit Ming Bryan and another Civil Procedure – Pleadings 16 May 2011 Kan Ting Chiu J: 1 The plaintiff Ng Chee Weng applied to amend his Statement of Claim against the defendants. Some of the amendments were dismissed by an Assistant Registrar (“AR”), and the plaintiff appealed against the dismissal. I affirmed the AR’s decision and set out my grounds. Background 2 On 26 May 2009, when the plaintiff commenced the action against the defendants, he set out the basis of his claim in para 1 of the Statement of Claim: The Plaintiff was the beneficial owner of 50% of the shareholding in Sinco Technologies Pte Ltd (the “Company”) which was held in trust for the Plaintiff by the 1st Defendant up to April 2007. The Plaintiff was therefore entitled to dividend payments made whilst he was the beneficial owner of the 50% shareholding interests in the Company. 3 The Statement of Claim went on to state that the plaintiff had sold his shares in the company to the first defendant: 17. On or about late April or May 2007, the 1st Defendant approached the Plaintiff inquiring if the Plaintiff was interested in selling all his 50% shareholding in the Company to the 1st Defendant. -

Report of the Committee to Develop the Singapore Legal Sector

REPORT OF THE COMMITTEE TO DEVELOP THE SINGAPORE LEGAL SECTOR _________________________________________ FINAL REPORT SEPTEMBER 2007 Report of the Committee to Develop the Singapore Legal Sector Table of Contents 1 BACKGROUND....................................................................................................... 1 2 LEGAL EDUCATION ............................................................................................. 2 (A) Legal Academia............................................................................................ 3 (I) Changing Legal Education Landscape......................................... 3 (II) Synergy between Academia and Industry .................................. 5 (III) Recommendations........................................................................... 5 (B) ‘A’ Level Law................................................................................................ 7 (I) Potential Benefits of Introducing ‘A’ Level Law......................... 8 (II) Costs of Implementing ‘A’ Level Law.......................................... 8 (III) Recommendation............................................................................. 9 (C) Restructuring the Present Legal Education System.............................. 9 (I) Admission Criteria for Law Schools............................................. 9 (II) Structure of the LLB Course..........................................................10 (III) Review of Content..........................................................................12 -

SAL Annual Report 2001

SINGAPORE ACADEMY OF LAW ANNUAL REPORT Financial year 2001/2002 MISSION STATEMENT Building up the intellectual capital, capability and infrastructure of members of the Singapore Academy of Law. Promotion of esprit de corps among members of the Singapore Academy of Law. SINGAPORE ACADEMY OF LAW ANNUAL REPORT 1 April 2001 - 31 march 2002 5Foreword 7Introduction 13 Annual Report 2001/2002 43 Highlights of the Year 47 Annual Accounts 2001/2002 55 Thanking the Fraternity Located in City Hall, the Singapore Academy of Law is a body which brings together the legal profession in Singapore. FOReWoRD SINGAPORE ACADEMY OF LAW FOREWORD by Chief Justice Yong Pung How President, Singapore Academy of Law From a membership body in 1988 with a staff strength of less than ten, the Singapore Academy of Law has grown to become an internationally-recognised organisation serving many functions and having two subsidiary companies – the Singapore Mediation Centre and the Singapore International Arbitration Centre. The year 2001/2002 was a fruitful one for the Academy and its subsidiaries. The year kicked off with an immersion programme in Information Technology Law for our members. The inaugural issue of the Singapore Academy of Law Annual Review of Singapore Cases 2000 was published, followed soon after by the publication of a book, “Developments in Singapore Law between 1996 and 2000”. The Singapore International Arbitration Centre launched its Domestic Arbitration Rules in May 2001, and together with the Singapore Mediation Centre, launched the Singapore Domain Name Dispute Resolution Policy for resolving “.sg” domain name disputes. The Academy created a Legal Development Fund of $5 million to be spread over 5 years for the development of the profession in new areas of law and practice. -

Cavinder Bull CV

Cavinder Bull, SC Chief Executive Officer B.A. (Hons), Oxford University (UK, 1992) M.A. Oxford University (UK, 2001) LL.M., Harvard Law School (USA, 1996) Barrister of England & Wales (1993) Advocate & Solicitor of the Supreme Court of Singapore (1994) Attorney-at-Law of the state of New York (1996) Appointed Senior Counsel (2008) T: +65 6531 2416 F: +65 6533 3591 E: [email protected] ABOUT CAVINDER associate. In 1995, he was awarded the Lee Kuan Yew Scholarship and left for Harvard Cavinder is the Chief Executive Officer of Law School where he received an LL.M. He Drew & Napier. He has over 25 years of passed the New York Bar exams and was experience in complex litigation and admitted to practice in New York. Cavinder international arbitration. He is engaged in trial practiced as a litigation associate with Sullivan and appellate advocacy at all levels of the & Cromwell in New York until late 1997 when Singapore Courts and appears as counsel in he returned to Singapore and Drew & Napier. international arbitration in various countries. He was made a partner of Drew & Napier in He is also co-head of the Competition Law & 1998 and a Director of the firm in May 2002. Regulatory Practice. He was appointed Senior Counsel by the Cavinder has acted as counsel in both Chief Justice of Singapore in 2008, one of a commercial and investor-state cases; and has handful to have been accorded the honour experience acting for States and investors. He before the age of 40. has also sat as an arbitrator in investor-state Cavinder graduated with First Class Honours arbitrations under the auspices of ICSID, in law from Oxford University in 1992, winning NAFTA, the Permanent Court of Arbitration the Bellot Prize for Public International Law (PCA), International Court of Arbitration (ICC), from Trinity College. -

Rules of Court (Amendment No. 2) Rules 2015

1 S 278/2015 First published in the Government Gazette, Electronic Edition, on 14th May 2015 at 5.00 pm. No. S 278 SUPREME COURT OF JUDICATURE ACT (CHAPTER 322) RULES OF COURT (AMENDMENT NO. 2) RULES 2015 In exercise of the powers conferred on us by section 80 of the Supreme Court of Judicature Act and all other powers enabling us under any written law, we, the Rules Committee, make the following Rules: Citation and commencement 1. These Rules may be cited as the Rules of Court (Amendment No. 2) Rules 2015 and come into operation on 15 May 2015. Amendment of Order 110 2. Order 110 of the Rules of Court (R 5) is amended –– (a) by deleting sub-paragraph (d) of Rule 28(2) and substituting the following sub-paragraph: “(d) state –– (i) whether the person is –– (A) an advocate and solicitor who has in force a practising certificate; (B) admitted to practise as an advocate and solicitor under section 15 of the Legal Profession Act (Cap. 161); or (C) registered under section 36P of the Legal Profession Act; and (ii) if the person is registered under section 130N of the Legal Profession Act, that the person is so registered;”; (b) by inserting, immediately after the words “registered foreign lawyer” in Rule 32(a), the words “or by a solicitor registered under section 130N of the Legal Profession Act (Cap. 161)”; S 278/2015 2 (c) by deleting the words “(Cap. 161)” in Rule 32(b); (d) by inserting, immediately after the words “registered foreign lawyer” in the heading of Rule 32, the words “or by solicitor registered under section 130N of Legal Profession Act”; and (e) by inserting, immediately after the words “by a foreign lawyer” in Rule 37(5)(b), the words “, or by a solicitor registered under section 130N of the Legal Profession Act (Cap.