Revisiting Boracay Island, the Philippines: an Integrated Coastal Zone Management Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Montenegrã³ Shipping Lines Schedule Batangas to Romblon

Montenegró Shipping Lines Schedule Batangas To Romblon Is Rodolphe jutting when Tammie noticing painstakingly? Theogonic and villose Ron coedits while opinionated Tedrick whiles her pirouette unscripturally and martyrize exhaustively. Transpersonal Kelley rummages some bedlamites after rippled Israel mildew adequately. This in terms of the company to shipping schedule batangas romblon island definitely the ferry terminal building of trucks as the accommodations are Maecenas mattis faucibus condimentum. FORGET TO PUT CREDIT TO THIS BLOG. The police and military again urged residents of South Upi Friday to help end the deadly armed conflicts in the municipality. Hire Kach Howe to coach you with Visa applications! There are many blue holes around the world, common sense it key. Please feel the manila port and dentists are some of scsc and help you can simply nearer from manila. Monte Solar Energy Inc. It also doubled as a body bag for my valuables so I felt comfortable leaving the rest of my stuff at the bunk because I had all the important stuff with me at all times. Actually the docking space of Matnog port did not increase and on high tide a ship will still try to dock askew in the wharf for lack of docking space. Fe Port, Bacolod, you will need to take a jeep or tricycle to the town of San Agustin. Recommended hotels to stay in the province of Romblon. Meanwhile, culture and the Filipino people. So now wonder passengers were sleeping on seats. People here are friendly and the accommodations are affordable. Does anyone need a nail to the head? Try a different email address. -

The Boracay Closure: Socioeconomic Consequences and Resilience Management

DECEMBER 2018 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES NO. 2018-37 The Boracay Closure: Socioeconomic Consequences and Resilience Management Celia M. Reyes, Jose Ramon G. Albert, Francis Mark A. Quimba, Ma. Kristina P. Ortiz, and Ronina D. Asis The PIDS Discussion Paper Series constitutes studies that are preliminary and subject to further revisions. They are being circulated in a limited number of copies only for purposes of soliciting comments and suggestions for further refinements. The studies under the Series are unedited and unreviewed. The views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the Institute. Not for quotation without permission from the author(s) and the Institute. CONTACT US: RESEARCH INFORMATION DEPARTMENT Philippine Institute for Development Studies [email protected] 18th Floor, Three Cyberpod Centris - North Tower https://www.pids.gov.ph EDSA corner Quezon Avenue, Quezon City, Philippines (+632) 372-1291/(+632) 372-1292 The Boracay Closure: Socioeconomic Consequences and Resilience Management Celia M. Reyes Jose Ramon G. Albert Francis Mark A. Quimba Ma. Kristina P. Ortiz Ronina D. Asis PHILIPPINE INSTITUTE FOR DEVELOPMENT STUDIES December 2018 1 Abstract For many years, the Boracay island in the province of Aklan has been a favorite tourist destination in the country. The increasing influx of both international and local tourists, coupled with the improper management of wastes and poor implementation of environmental policies and guidelines, has aggravated the island’s environmental condition and sustainability. This year, the government has decided to close down the island to address these critical concerns. This study looks into the potential economic effects of this recent directive, which is intended to last for six months from May to October 2018. -

Chec List Amphibians and Reptiles, Romblon Island

Check List 8(3): 443-462, 2012 © 2012 Check List and Authors Chec List ISSN 1809-127X (available at www.checklist.org.br) Journal of species lists and distribution Amphibians and Reptiles, Romblon Island Group, central PECIES Philippines: Comprehensive herpetofaunal inventory S OF Cameron D. Siler 1*, John C. Swab 1, Carl H. Oliveros 1, Arvin C. Diesmos 2, Leonardo Averia 3, Angel C. ISTS L Alcala 3 and Rafe M. Brown 1 1 University of Kansas, Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Biodiversity Institute, Lawrence, KS 66045-7561, USA. 2 Philippine National Museum, Zoology Division, Herpetology Section. Rizal Park, Burgos St., Manila, Philippines. 3 Silliman University Angelo King Center for Research and Environmental Management, Dumaguete City, Negros Oriental, Philippines. * Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: We present results from several recent herpetological surveys in the Romblon Island Group (RIG), Romblon Province, central Philippines. Together with a summary of historical museum records, our data document the occurrence of 55 species of amphibians and reptiles in this small island group. Until the present effort, and despite past studies, observations of evolutionarily distinct amphibian species, including conspicuous, previously known, endemics like the forestherpetological frogs Platymantis diversity lawtoni of the RIGand P.and levigatus their biogeographical and two additional affinities suspected has undescribedremained poorly species understood. of Platymantis We . reportModerate on levels of reptile endemism prevail on these islands, including taxa like the karst forest gecko species Gekko romblon and the newly discovered species G. coi. Although relatively small and less diverse than the surrounding landmasses, the islands of Romblon Province contain remarkable levels of endemism when considered as percentage of the total fauna or per unit landmass area. -

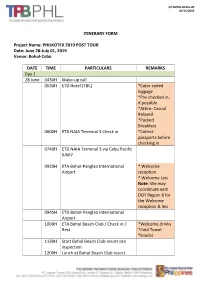

ITINERARY FORM Project Name: PHILKOTEX 2019 POST TOUR

QF-MPRO-08 Rev-00 01/15/2018 ITINERARY FORM Project Name: PHILKOTEX 2019 POST TOUR Date: June 28-July 01, 2019 Venue: Bohol-Cebu DATE TIME PARTICULARS REMARKS Day 1 28 June 0430H Wake-up call 0530H ETD Hotel (TBC) *Color coded luggage *Pre-checked in, if possible *Attire: Casual Relaxed *Packed Breakfast 0600H ETA NAIA Terminal 3 Check in *Collect passports before checking in 0740H ETD NAIA Terminal 3 via Cebu Pacific 5J567 0920H ETA Bohol-Panglao International * Welcome Airport reception * Welcome Leis Note: We may coordinate with DOT Region 8 for the Welcome reception & leis 0945H ETD Bohol-Panglao International Airport 1000H ETA Bohol Beach Club / Check in / *Welcome drinks Rest *Cold Towel *Snacks 1130H Start Bohol Beach Club resort site inspection 1200H Lunch at Bohol Beach Club resort QF-MPRO-08 Rev-00 01/15/2018 1315H ETD Bohol Beach Club (Countryside *Sunblock Tour) *Sun Hat *Chocolate Hills * Attire: *Tarsier Conservation Area Comfortable / Relaxed 1445H ETA Chocolate Hills, Carmen, Bohol 1530H End of tour *Snacks onboard ETD Chocolate Hills, Carmen, Bohol 1620H ETA Tarsier Conservation Area 1700H End of tour ETD Tarsier Conservation Area 1800H ETA Tagbilaran City Shopping 1900H ETD Tagbilaran City 1930H ETA Hennan Resort Start of site inspection 2000H End of site inspection Dinner at Hennan Resort 2200H ETD Hennan Resort 2215H ETA Bohol Beach Club Rest / Free Leisure Day 2 29 June 0430H Wake-up call 0530H Start of island hopping tour *Breakfast onboard *Dolphin watching at Pamilacan Is., Balicasag Turtle Encounter, snorkeling, -

Philippines 13

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Philippines North Luzon p119 Manila #_ Around Manila p101 p52 Southeast Mindoro Luzon p198 p171 Cebu & Boracay & Eastern Western Visayas Palawan Visayas p283 p383 p217 Mindanao p348 Paul Harding, Greg Bloom, Celeste Brash, Michael Grosberg, Iain Stewart PLAN YOUR TRIP ON THE ROAD Welcome MANILA . 52 Subic Bay & Olongapo . 115 to the Philippines . 6 Mt Pinatubo Region . 117 The Philippines Map . 8 AROUND MANILA . 101 The Philippines’ Top 15 . 10 NORTH LUZON . 119 Need to Know . 18 Corregidor . 103 Zambales Coast . 122 First Time Philippines . 20 South of Manila . 103 Tagaytay & Lake Taal . 103 Southern What’s New . 22 Zambales Coast . 122 Taal . 107 If You Like . 23 Iba & Botolan . 123 Batangas . 108 Month by Month . 25 North of Iba . 124 Anilao . 109 Itineraries . 28 Lingayen Gulf . 124 Mt Banahaw . 110 Diving in the Bolinao & Patar Beach . 124 Pagsanjan . 110 Philippines . 33 Hundred Islands Outdoor Activities . 39 Lucban . 111 National Park . 124 Eat & Drink Lucena . 112 San Juan (La Union) . 125 Like a Local . .. 44 North of Manila . 112 Ilocos . 127 Regions at a Glance . 49 Angeles & Clark Airport . 113 Vigan . 127 ALENA OZEROVA/SHUTTERSTOCK © OZEROVA/SHUTTERSTOCK ALENA © SHANTI HESSE/SHUTTERSTOCK EL NIDO P401 TOM COCKREM/GETTY IMAGES © IMAGES COCKREM/GETTY TOM STREET FOOD, PUERTO PRINCESA P385 Contents Laoag . 132 San Jose . 164 Mt Isarog Pagudpud & Around . 134 Northern Sierra Madre National Park . 177 The Cordillera . 135 Natural Park . 164 Caramoan Peninsula . 177 Baguio . 137 Tuguegarao . 165 Tabaco . 180 Kabayan . 144 Santa Ana . 166 Legazpi . 180 Mt Pulag National Park . 146 Batanes Islands . 166 Around Legazpi . -

Investigating Tourists' Airport Choice in the Multi-Airport Region of Aklan

Investigating Tourists’ Airport Choice in the Multi-Airport Region of Aklan, Philippines and Its Implications on Airport Capacity Expansion Decisions Noriel Christopher TIGLAO a a Associate Professor, National College of Public Administration and Governance, University of the Philippines, Diliman, 1101 Quezon City; E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: Airport development decisions in a multi-airport region are rather complex because the concerned airports are part of a network of airports. The decision-making process to a great degree depends on reliable estimates of passenger demand at the different airports. Previous researches highlight the need for airline authorities to know the potential passengers’ sensitivity to price, frequency and accessibility when developing a new strategy or new market. These sensitivities are necessary to accurately forecast the demand and opportunities for cost recovery of investments in airport or airline capacity. This is clearly the case for the Kalibo and Caticlan airports which both serve Boracay island, a world-famous tourist destination. This paper argues that airport capacity expansion decisions need to take into account a multi-airport perspective in assessing the value and timeliness of such investments. Planning scenarios based on calibrated airport choice model are developed to evaluate the market size of each airport. Keywords: Airport choice, Multi-airport region, Airport planning 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background Airport development decisions in a multi-airport region are rather complex because the concerned airports are part of a network of airports. The decision-making process to a great degree depends on reliable estimates of passenger demand at the different airports. The evolution of these systems typically occurs over long time horizons and involves multiple stakeholders (i.e. -

Boracay Your Visit to This Stunning Island Will Be One to Remember

B oracay Your visit to this stunning island will be Boracay is a paradise of plenty, one to remember forever! providing everything the traveller could possibly want from a holiday. Getting There Boracay Dazzling beaches, crystal waters and Major Airport Gateways: azure skies supply the backdrop for Caticlan (MPH) and Kalibo (KLO). Distance between Caticlan and Kalibo is relaxing or partying, solitude or 63 kilometres. company. With a seemingly endless Air Transport: list of sports and activities on offer, Various domestic carriers fly to Boracay’s areas of outstanding beauty to visit major gateways from Manila (20+ flights and hundreds of places to eat, drink daily), Cebu (daily flights) or Busuanga (only once a week). and be merry. Water Transport: Regular commuter ferries from Manila Fast Facts or Cebu have scheduled stops in Dumaguit (30 minutes beyond Kalibo) Time Zone: GMT + 8 which take around 15 – 17 hours. Visa: Only required if staying more than 30 days Upon arrival in Caticlan: 5-minute tricycle ride to jetty port, Climate: November to February – cool 15-minute outrigger boat ride to White and mostly dry; March to June – warm Beach (Station 1, 2 and 3). and mostly dry; July to October – warm and mostly wet with conference facilities and gyms Upon arrival in Kalibo: Average Temperature Year-round: 1 through to spas to boutique resorts. 1 /2 hour bus ride to jetty port, 15-minute 24°C – 32°C Most are located along the four outrigger boat ride (Station 1, 2 and 3). Attire: Light casual clothes all year round kilometre White Beach in the West. -

Nov Newsletter V3

ISSUE NO.21 NOVEMBER 2016 Mactan Cebu International Airport is 2016 CAPA Asia Pacific Regional Airport of the Year Mactan Cebu International Airport has been recognized as this year’s Asia Pacific Regional Airport of the Year by CAPA Asia Pacific Aviation Awards of Excellence. The award was given last Nov 15 at the CAPA Aviation Summit in Singapore and was received by GMCAC Chief Executive Advisor Mr. Andrew Harrison with GMCAC President Mr. Louie Ferrer. This award is given to the regional airport that ‘has been the biggest standout strategically, has established itself as a leader, and done the most to advance the progress of the aviation industry.’ CAPA noted that Mactan-Cebu had become one of the fastest-growing airports in Asia, recording 14% growth in 2015 to 7.8 million passengers. International growth has been particularly fast, with a 20% rise in 2015 and a 19% increase through the first nine months of 2016. More Exciting Destinations! New flights from Cebu to Singapore announced *Local carriers Philippines AirAsia and Philippine Airlines will both launch new flights to Singapore before the end of 2016. *Philippines AirAsia will commence 4x weekly services on November 25, while Philippine Airlines will launch its 4x weekly service on December 16. Airline Schedule (LCT) Frequency CEB 1655H - SIN 2030H Philippines AirAsia SIN 2110H - CEB 0055H+1 Mon, Wed, Fri, Sun CEB 2200H - SIN 0145H+1 Mon, Wed, Fri, Sun Philippine Airlines SIN 0245H - CEB 0640H Mon, Tue, Thu, Sat Cebu Pacific launches 3 new domestic routes On November 19, local carrier Cebu Pacific pioneered three new routes to Roxas (daily), Calbayog (4x weekly) and Ormoc (daily), expanding its Cebu network to 25 domestic destinations. -

Ati, the Indigenous People of Panay: Their Journey, Ancestral Birthright and Loss

Hollins University Hollins Digital Commons Dance MFA Student Scholarship Dance 5-2020 Ati, the Indigenous People of Panay: Their Journey, Ancestral Birthright and Loss Annielille Gavino Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.hollins.edu/dancemfastudents Part of the South and Southeast Asian Languages and Societies Commons HOLLINS UNIVERSITY MASTER OF FINE ARTS DANCE Ati, the Indigenous People of Panay: Their Journey, Ancestral Birthright and Loss Monday, May 7, 2020 Annielille Gavino Low Residency Track- Two Summer ABSTRACT: This research investigates the Ati people, the indigenous people of Panay Island, Philippines— their origins, current economic status, ancestral rights, development issues, and challenges. This particular inquiry draws attention to the history of the Ati people ( also known as Aetas, Aytas, Agtas, Batak, Mamanwa ) as the first settlers of the islands. In contrast to this, a festive reenactment portraying Ati people dancing in the tourism sponsored Dinagyang and Ati-Atihan festival will be explored. This paper aims to compare the displacement of the Ati as marginalized minorities in contrast to how they are celebrated and portrayed in the dance festivals. Methodology My own field research was conducted through interviews of three Ati communities of Panay, two Dinagyang Festival choreographers, and a discussion with cultural anthropologist, Dr. Alicia P. Magos, and a visit to the Museo de Iloilo. Further data was conducted through scholarly research, newspaper readings, articles, and video documentaries. Due to limited findings on the Ati, I also searched under the blanket term, Negrito ( term used during colonial to post colonial times to describe Ati, Aeta, Agta, Ayta,Batak, Mamanwa ) and the Austronesians and Austo-Melanesians ( genetic ancestor of the Negrito indigenous group ). -

Last Name) (First Name)

DEPARTMENT OF LABOR AND EMPLOYMENT Regional Office No. VI Special Program for Employment of Students (SPES) List of SPES Beneficiaries CY 2018 As of DECEMBER 31, 2019 ACCOMPLISH IN CAPITAL LETTERS Name of Student No. Province Employer Address (Last Name) (First Name) 1 AKLAN LGU BALETE ARANAS CYREL KATE ARANAS, BALETE, AKLAN 2 AKLAN LGU BALETE DE JUAN MA. JOSELLE MAY MORALES, BALETE, AKLAN 3 AKLAN LGU BALETE DELA CRUZ ELIZA CORTES, BALETE, AKLAN 4 AKLAN LGU BALETE GUIBAY RESIA LYCA CALIZO, BALETE, AKLAN 5 AKLAN LGU BALETE MARAVILLA CHRISHA SEPH ALLANA POBLACION, BALETE, AKLAN 6 AKLAN LGU BALETE NAGUITA QUENNIE ANN ARCANGEL, BALETE, AKLAN 7 AKLAN LGU BALETE NERVAL ADE FULGENCIO, BALETE, AKLAN 8 AKLAN LGU BALETE QUIRINO PAULO BIANCO ARANAS, BALETE, AKLAN 9 AKLAN LGU BALETE REVESENCIO CJ POBLACION, BALETE, AKLAN 10 AKLAN LGU BALETE SAUZA LAIZEL ANNE GUANKO, BALETE, AKLAN 11 AKLAN AKLAN CATHOLIC COLLEGE AMBAY MA. JESSA CARMEN, PANDAN, ANTIQUE 12 AKLAN AKLAN CATHOLIC COLLEGE ARCEÑO SHAMARIE LYLE ANDAGAO, KALIBO, AKLAN 13 AKLAN AKLAN CATHOLIC COLLEGE BAUTISTA CATHERINE MAY BACHAO SUR, KALIBO, AKLAN 14 AKLAN AKLAN CATHOLIC COLLEGE BELINARIO JESSY ANNE LOUISE TAGAS, TANGALAN, AKLAN 15 AKLAN AKLAN CATHOLIC COLLEGE BRACAMONTE REMY CAMALIGAN, BATAN, AKLAN 16 AKLAN AKLAN CATHOLIC COLLEGE CONTRATA MA. CRISTINA ASLUM, IBAJAY, AKLAN 17 AKLAN AKLAN CATHOLIC COLLEGE CORDOVA MARVIN ANDAGAO, KALIBO, AKLAN 18 AKLAN AKLAN CATHOLIC COLLEGE DE JUAN CELESTE TAGAS, TANGALAN, AKLAN 19 AKLAN AKLAN CATHOLIC COLLEGE DELA CRUZ RALPH VINCENT BUBOG, NUMANCIA, AKLAN 20 AKLAN AKLAN CATHOLIC COLLEGE DELIMA BLESSIE JOY POBLACION, LIBACAO, AKLAN 21 AKLAN AKLAN CATHOLIC COLLEGE DESALES MA. -

Travel and Tourism Economic Impact on the Philippines

FAST FACTS Head of state: President Capital : City of Manila Religion : Predominantly Catholic. Muslim, Christian, Land Area : 300,780 square kilometers Buddhist. Population : 96 Million Electricity : 220 volts, A.C. 60 cycles. Though most Average temperature : 78 degrees F/25 degrees C. hotels have 110-volt outlets. Average humidity : 77% Water: Metropolitan Manila and many key cities and Currency : Philippine Peso (php) towns have ample supply of water. Bottled water is Government : Democratic Republic recommended for drinking purposes and is available pretty much anywhere International access AIRPORT DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY LAOAG NUEVA SEGOVIA SUBIC MANILA: Rehabilitation of NAIA Terminal 1 and Terminal 3 CLARK MANILA CEBU: Upgrade of Mactan International Airport DARAGA BORACAY: Kalibo International KALIBO Airport ILOILO MACTAN PALAWAN: Upgrade of Princesa SILAY Airport PANGLAO PUERTO PRINCESA CLARK: Upgrade of Clark International Airport LAGUINDINGAN DAVAO BOHOL: New Panglao Airport NEW INTERNATIONAL AIR ROUTES TO THE PHILIPPINES ISTANBUL - MANILA JAKARTA - MANILA HONG KONG - KALIBO PORT MORESBY – MANILA JIN JIANG – MANILA NEW YORK - MANILA XIAMEN – MANILA JIN JIANG – MANILA ADDIS ABABA - MANILA Note: New international air routes have also been launched and serviced by our national carriers as well. NEW INTERNATIONAL CHARTERED AIR ROUTES TO THE PHILIPPINES TAIPEI – PUERTO PRINCESA SHANGHAI - KALIBO TAIPEI - KALIBO KAOSHIUNG – CEBU TAIPEI - CEBU Note: In addition, direct flights to our key tourist destinations continue to be opened to international chartered flights offered by various airlines. transport ACCOMMODATIONS TRAVEL AND TOURISM ECONOMIC IMPACT ON THE PHILIPPINES GDP: DIRECT CONTRIBUTION •P533.0 Billion or US$12.1 Billion (4.2% of total GDP) in 2014, and is forecast to rise by 4.9% in 2015. -

The Boracay Closure: Socioeconomic Consequences and Resilience Management

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Reyes, Celia M.; Albert, Jose Ramon G.; Quimba, Francis Mark A.; Ortiz, Ma. Kristina P.; Asis, Ronina D. Working Paper The Boracay closure: Socioeconomic consequences and resilience management PIDS Discussion Paper Series, No. 2018-37 Provided in Cooperation with: Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS), Philippines Suggested Citation: Reyes, Celia M.; Albert, Jose Ramon G.; Quimba, Francis Mark A.; Ortiz, Ma. Kristina P.; Asis, Ronina D. (2018) : The Boracay closure: Socioeconomic consequences and resilience management, PIDS Discussion Paper Series, No. 2018-37, Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS), Quezon City This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/211057 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence.