1 on ACTING @ IU South Bend; Why We Do What We Do When We Do It

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dr. Katie Bird Curriculum Vitae, Sept 2019

Dr. Katie Bird Curriculum Vitae, Sept 2019 Department of Communication University of Texas – El Paso 301 Cotton Memorial El Paso, TX 79968 kebird[at]utep.edu EDUCATION Ph.D. Film and Media Studies, Department of English. University of Pittsburgh. August, 2018 Dissertation: “‘Quiet on Set!: Craft Discourse and Below-the-Line Labor in Hollywood, 1919- 1985” Committee: Mark Lynn Anderson (chair), Adam Lowenstein, Neepa Majumdar, Randall Halle, Daniel Morgan (University of Chicago), Dana Polan (New York University) Fields: Filmmaking, Media Industries, Technology, American Film Industry History, Studio System, Below-the-Line Production Culture, Cultural Studies, Exhibition/Institutional History, Labor History, Film Theory M.A. Literary and Cultural Studies, Department of English, Carnegie Mellon University, 2010 Thesis length project: “Postwar Movie Advertising in Exhibitor Niche Markets: Pittsburgh’s Art House Theaters, 1948-1968” B.A. Film Production, School of Film and Television, Loyola Marymount University, 2007 B.A. Creative Writing, English Department, Loyola Marymount University, 2007 PROFESSIONAL APPOINTMENTS 2019 TT Assistant Professor, Film Studies and Digital Media Production. Department of Communication. University of Texas, El Paso (UTEP) 2018 Visiting Lecturer, Film and Media Studies/Filmmaking. Department of English. University of Pittsburgh 2017 Digital Media Learning Coordinator, Visiting Instructor. Department of English. University of Pittsburgh PUBLICATIONS 2021 Forthcoming. “Sporting Sensations: Béla Balázs and the Bergfilm Camera Operator.” Bird 1 Journal of Cinema and Media Studies/Cinema Journal. Spring 2021. 2020 Forthcoming. “Steadicam Style, 1972-1985” [In]Transition. Spring 2020. 2018 “The Editor’s Face on the Cutting Room Floor: Fredrick Y. Smith’s Precarious Promotion of the American Cinema Editors, 1942-1977.” The Spectator (special issue: “System Beyond the Studios,” guest edited by Luci Marzola) 38, no. -

The Still Photographer

_____________________________________________________________________________ ______ The Still Photographer (Stills/Portrait Photographer) by Kim Gottlieb-Walker, Doug Hyun, Ralph Nelson, David James, Melinda Sue Gordon and Byron Cohen Duties The Still/Portrait Photographer's primary job is to interpret the project in single frames which accurately represent the story, production value, stars, and feeling of the show. These images are used to publicize, entice, and seduce the potential audience into watching the show. Whenever the public is exposed to images other than video or film regarding a show, they must be shot by the unit still photographer. The still person will work both during actual filming/taping, during rehearsals, on or off the set. He or she will shoot available light but is also capable of doing fully lit shoots with either his own lighting or in conjunction with production. More specifically, the still photographer takes production stills that the publicity department can use to promote the film or television show in press kits and various print media and the increasingly important DVD stills galleries. This includes characteristic shots of each scene, shots which show the actors acting together, shots which give a feeling of the look and atmosphere of the show, good character shots of the actors, shots of the director directing, special effects being rigged, special make-up being created, anything which could be supplied to the regular or genre press or used later on the DVD to promote interest in and expand knowledge about a production. But beyond that, because the Still Photographer is the only person on the set authorized to take photographs, he or she may, if time allows, serve some of the photographic needs of the crew. -

L'effet Steadicam

NEWS FOR OPERATORS AND OWNERS ~ \ Pour En Finir Avec "L'effet Report from Steadicam" South Africa - - - -------- - -------------- ------ by Jean Marc Bringuier to the already abundant range of Chris faces many of the same devices aimed at gliding a camera in problems we all do, plus a few that The complete article originally space. are unique to his troubled land. appeared in Cahiers Du Cinema . The only va lid use offilm We've talked many times over the last In this excerpt , Jean Mar c has equipment, ho wever sophisticated or f ew years , including last spring when exci ting, is to help tell a story or instill [ was in South Africa. -Ed. given us a Gallic feast ofideas a visual atmosphere. It does requ ire _. _- . ~ ----- that are useful f or discussions with individuals to stru ggle with it. I'm not operators, novices, and producers. ju st hinting at the sweat dripping from Ch r is Haarhoff: I recently -Ed . the operator's face (nor at the produ c alam agated my Stead icam with a great tion manager's pallor. ..) for Cinem a rental house down here, the Movie Panaglide and Steadicam are will always be a team sport. It was Camera Company. They were unable tools a filmmaker may use to stabilize certainly not the dollies used by to resurect their own Steadicam, a some of his views of the world. They Hitchcock which created the well Mod el II, and so I joined forces with are expected to free the creators' known suspense, through some hidd en their ow n in house ope rator, Gi lbert minds of several old constraints of the secret of their technology, but indeed Reed , thus reinforcin g the we ll held traditional and subtle art of dealin g the inimitable style of this Aristoc rat Stead icarn notion that unity is with the logistics of moving a film of Vision. -

The Grip Book

THE GRIP BOOK FOURTH EDITION 01-FM-K81291.indd i 9/4/09 11:15:20 AM 01-FM-K81291.indd ii 9/4/09 11:15:20 AM The Grip Book FOURTH EDITION Michael G. Uva AMSTERDAM • BOSTON • HEIDELBERG • LONDON NEW YORK • OXFORD • PARIS • SAN DIEGO SAN FRANCISCO • SINGAPORE • SYDNEY • TOKYO Focal Press is an imprint of Elsevier 01-FM-K81291.indd iii 9/4/09 11:15:20 AM Focal Press is an imprint of Elsevier 30 Corporate Drive, Suite 400, Burlington, MA 01803, USA Linacre House, Jordan Hill, Oxford OX2 8DP, UK Copyright © 2010 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Details on how to seek permission, further information about the Publisher’s permissions policies and our arrangements with organizations such as the Copyright Clearance Center and the Copyright Licensing Agency, can be found at our website: www.elsevier.com/permissions. This book and the individual contributions contained in it are protected under copyright by the Publisher (other than as may be noted herein). Notices Knowledge and best practice in this fi eld are constantly changing. As new research and experience broaden our understanding, changes in research methods, professional practices, or medical treatment may become necessary. Practitioners and researchers must always rely on their own experience and knowledge in evaluating and using any information, methods, compounds, or experiments described herein. In using such information or methods they should be mindful of their own safety and the safety of others, including parties for whom they have a professional responsibility. -

Pact BECTU Feature Film Agreement Grade Ladder PAY GROUP

Pact BECTU Feature Film Agreement Grade Ladder PAY GROUP 12 Armourer 1 All Runners Board Operator Boom Operator 2 Art Dept Junior Chargehand Props Camera Trainee Electrician Costume Trainee Post Prod. Supervisor Directors Assistant Production Buyer Electrical Trainee / junior Rigging Electrician Jnr Costume Asst Senior Make-up Artist Make-up Traineee SFX Technician Producers Assistant Stand-by Art Director Production Secretary Props Trainee / junior 13 1st Asst. Editor Script Supervisor's Assistant Art Director Sound Trainee / junior Convergence Puller DIT 3 2nd Assistant Editor 3rd Assistant Director 14 ?Crane Technician? Accounts Assistant/cashier Grip Art Dept Co-ordinator Location Manager Art Dept Assistant Prop Master Asst Production Co-ordinator Costume Assistant 15 Costume Supervisor Junior Make-up & Hair Best Boy Electrician Location Assistant Best Boy Grip Rigging Gaffer 4 Data Wrangler Make Up Supervisor Video Playback Operator Scenic Artist Script Supervisor 5 Assistant Art Director Sculptor Costume Dresser Set Decorator Costume Maker Stereographer AC Nurse Post Production Co--ordinator 16 Focus Puller Sound Asst (3rd man) Production Accountant Unit Manager Stills Photographer 6 Assistant SFX technician 17 Dubbing Editor Asst. Location Manager Researcher 18 1st Assistant Director Camera Operator 7 2nd Assistant Accountant Costume Designer Clapper Loader Gaffer Draughtsperson Hair & Make Up Chief/Designer Key Grip 8 Assistant Costume Designer Production Manager Dressing Props Prosthetic Make Up Designer Graphic Artist Senior SFX Technician Sound Recordist 9 Illustrator Supervising Art Director Stand By Construction Stand By Costume 19 Individual Negotiation => Stand By Props Casting Director Storyboard Artist Director Director of Photography 10 Make Up Artist Editor Production Co-Ordinator Line Producer / UPM Production Designer 11 1st Assistant Accountant SFX Supervisor 2nd Assistant Director Senior Video Playback Operator Storeman/Asst Prop Master . -

The Essential Reference Guide for Filmmakers

THE ESSENTIAL REFERENCE GUIDE FOR FILMMAKERS IDEAS AND TECHNOLOGY IDEAS AND TECHNOLOGY AN INTRODUCTION TO THE ESSENTIAL REFERENCE GUIDE FOR FILMMAKERS Good films—those that e1ectively communicate the desired message—are the result of an almost magical blend of ideas and technological ingredients. And with an understanding of the tools and techniques available to the filmmaker, you can truly realize your vision. The “idea” ingredient is well documented, for beginner and professional alike. Books covering virtually all aspects of the aesthetics and mechanics of filmmaking abound—how to choose an appropriate film style, the importance of sound, how to write an e1ective film script, the basic elements of visual continuity, etc. Although equally important, becoming fluent with the technological aspects of filmmaking can be intimidating. With that in mind, we have produced this book, The Essential Reference Guide for Filmmakers. In it you will find technical information—about light meters, cameras, light, film selection, postproduction, and workflows—in an easy-to-read- and-apply format. Ours is a business that’s more than 100 years old, and from the beginning, Kodak has recognized that cinema is a form of artistic expression. Today’s cinematographers have at their disposal a variety of tools to assist them in manipulating and fine-tuning their images. And with all the changes taking place in film, digital, and hybrid technologies, you are involved with the entertainment industry at one of its most dynamic times. As you enter the exciting world of cinematography, remember that Kodak is an absolute treasure trove of information, and we are here to assist you in your journey. -

Kentucky State Film Tax Credit Program Schedule of Qualified Expenditures

Kentucky State Film Tax Credit Program Schedule of Qualified Expenditures All Eligible Expenditures Must Be Made From Businesses Within The Commonwealth of Kentucky Description QUAL Additional Deliverables YES Additional Equipment YES Additional Hairstylists YES Additional labor YES Additional Makeup YES Additional Sound Labor YES Addl Equipment YES ADR Expenses(excluding talent) YES ADR Mixer and Stage YES Aircraft/Helicopter Rentals only for the purpose of filming YES AIRFARE NO All Transfer Costs YES Alterations & Repairs YES AMORT NO Animal Purchases/Rentals YES Animals YES Answer Prints YES Art Department YES Art Dept. Coordinator/PA YES Art Director and Assistants YES Assistant Film Editors YES Assistant Propmaster & Labor YES Assistants YES Assistants and Loaders YES Asst Location Managers & Scouts YES Atmosphere Cars YES Audience YES Bank Fees NO Bleachers/Drapes/Signage YES Boards/Budgets YES Boom Operator YES Box/Kit Rentals YES Camera YES Camera Cars/Insert Cars/Cranes YES Camera Purchases YES Camera Rentals YES Car Rental/Trailer YES Car Rentals YES Cast and Crew Screening NO All Eligible Expenditures Must Be Made From Businesses Within The Commonwealth of Kentucky Cast Exams YES Casting Assistants YES Casting Commission//Expenses YES Casting Director YES Casting Office Expenses YES Catered Meals YES Catering Labor YES CG Animation/Rigging YES CG Modeling YES Check Print YES Chief Lighting Technician YES Choreographers YES Cleaning YES Clearances/Licensing YES COMPLETION BOND NO Composers YES Compositing YES Computers Rentals YES Concept Design & Look Dev YES Construction YES Construction Coordinators YES Construction Foremen YES CONTINGENCY NO Continuity Script YES Costume Designer YES Craft Service Persons YES Craft Service Purchases YES Daily/Weekly Players YES Data I/O, Archiving & Deliverables YES Deductible YES Designer Staff YES Develop YES Dialogue Coach YES Digital Intermediate Inc. -

FAQ About Film Production — 1 Action Movie Makers Training

Action Movie makers training © 2016 FAQ About Film Production — www.actionmoviemakerstraining.com 1 Action Movie makers training FAQ About Film Production By Philippe Deseck July 2016 Content • About the Author • What is a Producer? • What is an Executive Producer? • What is a Line Producer? • What is a Supervising Producer? • What is a Co-Producer? • What is a Director? • What is a Unit Production Manager? • What is a 2nd Unit Director? • What is an Action Director? • What is an Assistant Director? • What is a Director of Photography? • What is a Script Supervisor? © 2016 FAQ About Film Production — www.actionmoviemakerstraining.com 2 Action Movie makers training • What is Sound Recordist? • What is a Video Split Operator? • What is a Key Grip? • What is a Gaffer? • What is a Safety Supervisor? • What is a Stunt Coordinator? • What is a Stunt Double? • What is a Stunt Rigger? • What is a Choreographer? • When is a Stunt Co-ordinator required on your Production? • An Example of all the Different Departments that work on a Feature Film © 2016 FAQ About Film Production — www.actionmoviemakerstraining.com 3 Action Movie makers training About the Author IMDB PROFILE: http://www.imdb.com/name/nm3455222/?ref_=fn_al_nm_1 Since a very young age Philippe has had a love for movies, particularly action movies from Hong Kong. Since 1994 Philippe has been actively involved in film, TV and radio whilst living in Thailand. Philippe’s movie credits include Street Fighter - where he was first introduced to stunt man Ronnie Vreeken, Operation Dumbo Drop and The Quest - where he met stunt man Alex Kuzelicki. -

Steadicam AERO Operator's Manual

Operator’s Manual LIT-825000 Revision: A Steadicam AERO Operator’s Manual LIT-825000 Revision: A Steadicam® is a registered trademark of The Tiffen Company. Steadicam® AERO™ is a trademark of The Tiffen Company. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. Specifications stated within this manual are subject to change without notice. Please see www.tiffen.com//warranty.html for warranty details. © 2016 The Tiffen Company. Written by E. Barthelman. Table of Contents A Word from Garrett Brown 1 Get to Know the Steadicam AERO 3 AERO components 4 Operating Accessories 7 Setting Up 9 Assembling the AERO Sled 10 Mounting your Camera 13 Balancing 19 Static Balance 20 The Steadicam Vest 27 Fitting the Vest 28 The Steadicam Arm 29 Connecting the Arm & Vest 30 Lifting the System 31 Adjusting the Arm & Threads 32 Steadicam Operating 35 Operating 101 36 Weights & Post Extension 41 Goofy Operating 45 Advanced Operating 47 Dynamic Balance 49 Maintenance 53 Cleaning 54 Electronics & Connectors 55 Contact Tiffen 57 A Word from Garrett Brown Dear Friends, Congratulations on your new Steadicam® AERO™. I’m amazed to say that Steadicam operating is now 40 years old and the equipment is seventh generation—and both are more sophisticated and more vital than ever! As each new Steadicam gets better and tougher, as great cameras become ever smaller, our lightweight versions increasingly resemble our ‘big rigs,’ with the same features and perks that help top operators nail difficult shots. The AERO™ is a true Steadicam top to bottom. It’s arguably stronger and more capable than any rig in its class, and is certainly a user-friendly choice for beginners. -

The Tools of Screenwriting

$14.95/ $17.25 Can. "What David Howard has done with The Tools of Screenwritin is to n The Tools of Screenwriting, David reveal for me and for all readers just Howard and �dward Mabley illuminate how stories work; he shows that the essential elements of cinematic there are no absolute rules, but there are principles that can help a begin storytelling, and reveal the central ning writer gain understanding of all · principles that all good screenplays the elements that go into the cre share. The authors address questions of ation of a'good story well told.' " dramatic structure, plot, dialogue, charac ter development, setting, imagery, and other crucial topics as they apply to the '�is the special art of filmmaking. best primer on the craft, far better than the usual paint-by-the-numbers Howard and Mabley also demonstrate sort of books that abound." how the tools of screenwriting work in six teen notable films, including Citizen Kane, �.T., One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, Rashomon, The Godfather, North by Northwest, Chinatown, and sex, lies and videotape. "As my screenwriting teacher, David The Tools of Screenwriting is an essen Howard made the underlying princi tial book for anyone who studies film or ples of screenwriting clear, accessi ble, and useful. The same can be said wants to write a screenplay. of his succinct and elegant book, which I've already used as a much needed refresher course. It's sitting "David Howard calls this book 'a next to my computer now, right next writer's guide.' I think it's a wonder to the thesaurus." ful and indispensable producer's guide to story, storytelling, and screenwriting." ISBN-13: 978-0-312-11908-9 ISBN-IO: 0-312-11908-9 51 495> I 1 9 "780312 119089 I PRAIS E FOR THIS BOOK "David Howard and Edward Mabley's The To ols of Screen writing is a prac tical, comprehensive guide for writers at all levels. -

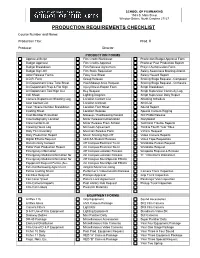

Production Requirements Checklist

SCHOOL OF FILMMAKING 1533 S. Main Street Winston-Salem, North Carolina 27127 PRODUCTION REQUIREMENTS CHECKLIST Course Number and Name: Production Title: Prod. # Producer: Director: PRODUCTION FORMS Approved Script Film Credit Worksheet Production Budget Approval Form Budget Approval Film Credits Approval Producer Post Production Report Budget Breakdown Film Release Agreement Project Authorization Form Budget Sign-Off Film Stock Requisition Safety Awareness Meeting Attend. Actor Release Forms Foley Cue Sheet Safety Hazard Report A.D.R. Form Group Release Scoring Stage Request - Composer Art Department Crew Time Sheet Hair/Makeup Artist Request Scoring Stage Request - Orchestra Art Department Prop & Flat Sign Injury/Illness Report Form Script Breakdown Art Department Tool Sign Out Key Request Script Supervisor Continuity Log Call Sheet Lighting Diagram Script Supervisor Daily Report Camera Department Shooting Log Location Contact List Shooting Schedule Cast Contact List Location Contract Shot List Cast / Scene Number Breakdown Location Fact Sheet Sound Report Casting Sheet Location Release Special Camera Rigging Cast Member Evaluation Makeup / Hairdressing Record Still Photo Release Cinematography Location Minor Release/Authorization Storyboard Crew Contact List Minor Release From School Technical Trouble Reports Crewing Hours Log Mix Lock Agreement Third & Fourth Year Titles Daily Film Inventory Musician Release Form Vehicle Request Daily Production Report Music Scoring Sign-Off Video Camera Reports Digital Effects Request UNCSA Student -

Glossary-Of-Film-Terms.Pdf

Glossary of Terms While there are many job descriptions on a film or television set, these are the people you might come into contact with: Assistant Director (A.D.): Carries out the Director’s instructions and runs the set. The First A.D. is responsible for preparing the production schedule and script breakdown, making sure shooting stays on schedule and on budget. The Second A.D. is responsible for distributing information and cast notifications, keeping track of hours worked by cast and crew, management of extras, signing actors in and out, preparing call sheets and is in charge of the Production Assistants. Buyer : Responsible for buying or renting props, furniture, costumes and other items on behalf of the Art Department. Art Director : Reports to the Producion Designer and directly supervises the art department as they design sets and create graphic art for the production design of the film. Works closely with the Construction Coordinator to oversee set construction. Best Boy: Chief assistant to either the gaffer or key grip. Responsible for the daily running of the lighting or grip department. Camera Operator: Operates the camera under instruction from the Director of Photography. Casting Director: Supplies actors for the film or television show. Construction Coordinator : AKA the Construction Manager, this person supervises and manages the physical construction of sets and reports to the Art Director and Production Designer. Craft Services: Provides on-set snacks and drinks for cast and crew. Not the same as the caterer. Director: The person in charge of the overall cinematic vision of the film and the performance of the actors.