Women, Peace & Security

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BEST PRACTICES in Anti-Terrorism Security for Sporting and Entertainment Venues RESOURCE GUIDE

Command, Control and Interoperability Center for Advanced Data Analysis A Department of Homeland Security University Center of Excellence BEST PRACTICES in Anti-Terrorism Security for Sporting and Entertainment Venues RESOURCE GUIDE July 2013 Table of Contents Introduction to the Project ............................................................................................................7 Background...................................................................................................................................8 Identifying Best Practices in Anti-Terrorism Security in Sports Venues ......................................8 Identifying the Key Best Practices and Developing Metrics for Each .........................................11 Developing a Best Practices Resource Guide .............................................................................13 Testing the Guid e ........................................................................................................................13 Executive Summary....................................................................................................................13 Chapter 1 – Overview.................................................................................................................15 1.1 Introduction...........................................................................................................................15 1.2 Risk Assessment ...................................................................................................................15 -

DDS Security Specification Will Have Limited Interoperability with Implementations That Do Implement the Mechanisms Introduced by This Specification

An OMG® DDS Security™ Publication DDS Security Version 1.1 OMG Document Number: formal/2018-04-01 Release Date: July 2018 Standard Document URL: https://www.omg.org/spec/DDS-SECURITY/1.1 Machine Consumable Files: Normative: https://www.omg.org/spec/DDS-SECURITY/20170901/dds_security_plugins_spis.idl https://www.omg.org/spec/DDS-SECURITY/20170901/omg_shared_ca_governance.xsd https://www.omg.org/spec/DDS-SECURITY/20170901/omg_shared_ca_permissions.xsd https://www.omg.org/spec/DDS-SECURITY/20170901/dds_security_plugins_model.xmi Non-normative: https://www.omg.org/spec/DDS-SECURITY/20170901/omg_shared_ca_governance_example.xml https://www.omg.org/spec/DDS-SECURITY/20170901/omg_shared_ca_permissions_example.xml Copyright © 2018, Object Management Group, Inc. Copyright © 2014-2017, PrismTech Group Ltd. Copyright © 2014-2017, Real-Time Innovations, Inc. Copyright © 2017, Twin Oaks Computing, Inc. Copyright © 2017, THALES USE OF SPECIFICATION – TERMS, CONDITIONS & NOTICES The material in this document details an Object Management Group specification in accordance with the terms, conditions and notices set forth below. This document does not represent a commitment to implement any portion of this specification in any company's products. The information contained in this document is subject to change without notice. LICENSES The companies listed above have granted to the Object Management Group, Inc. (OMG) a nonexclusive, royalty-free, paid up, worldwide license to copy and distribute this document and to modify this document and distribute copies of the modified version. Each of the copyright holders listed above has agreed that no person shall be deemed to have infringed the copyright in the included material of any such copyright holder by reason of having used the specification set forth herein or having conformed any computer software to the specification. -

Fedramp SECURITY ASSESSMENT FRAMEWORK

FedRAMP SECURITY ASSESSMENT FRAMEWORK Version 2.4 November 15, 2017 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This document describes a general Security Assessment Framework (SAF) for the Federal Risk and Authorization Management Program (FedRAMP). FedRAMP is a Government-wide program that provides a standardized approach to security assessment, authorization, and continuous monitoring for cloud-based services. FedRAMP uses a “do once, use many times” framework that intends to save costs, time, and staff required to conduct redundant Agency security assessments and process monitoring reports. FedRAMP was developed in collaboration with the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), the General Services Administration (GSA), the Department of Defense (DOD), and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). Many other Government Agencies and working groups participated in reviewing and standardizing the controls, policies and procedures. | i DOCUMENT REVISION HISTORY DATE VERSION PAGE(S) DESCRIPTION AUTHOR Major revision for NIST SP 800-53 Revision 4. 06/06/2014 2.0 All FedRAMP PMO Includes new template and formatting changes. Formatting changes throughout. Clarified distinction 12/04/2015 2.1 All between 3PAO and IA. Replaced Figures 2 and 3, and FedRAMP PMO Appendix C Figures with current images. 06/06/2017 2.2 Cover Updated logo FedRAMP PMO Removed references to CSP Supplied Path to 11/06/2017 2.3 All Authorization and the Guide to Understanding FedRAMP PMO FedRAMP as they no longer exist. 11/15/2017 2.4 All Updated to the new template FedRAMP PMO HOW TO CONTACT US Questions about FedRAMP or this document should be directed to [email protected]. For more information about FedRAMP, visit the website at http://www.fedramp.gov. -

Global Terrorism: IPI Blue Paper No. 4

IPI Blue Papers Global Terrorism Task Forces on Strengthening Multilateral Security Capacity No. 4 2009 INTERNATIONAL PEACE INSTITUTE Global Terrorism Global Terrorism Task Forces on Strengthening Multilateral Security Capacity IPI Blue Paper No. 4 Acknowledgements The International Peace Institute (IPI) owes a great debt of gratitude to its many donors to the program Coping with Crisis, Conflict, and Change. In particular, IPI is grateful to the governments of Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, Greece, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. The Task Forces would also not have been possible without the leadership and intellectual contribution of their co-chairs, government representatives from Permanent Missions to the United Nations in New York, and expert moderators and contributors. IPI wishes to acknowledge the support of the Greentree Foundation, which generously allowed IPI the use of the Greentree Estate for plenary meetings of the Task Forces during 2008. note Meetings were held under the Chatham House Rule. Participants were invited in their personal capacity. This report is an IPI product. Its content does not necessarily represent the positions or opinions of individual Task Force participants. suggested citation: International Peace Institute, “Global Terrorism,” IPI Blue Paper No. 4, Task Forces on Strengthening Multilateral Security Capacity, New York, 2009. © by International Peace Institute, 2009 All Rights Reserved www.ipinst.org CONTENTS Foreword, Terje Rød-Larsen. vii Acronyms. x Executive Summary. 1 The Challenge for Multilateral Counterterrorism. .6 Ideas for Action. 18 I. strengThen Political SupporT For The un’S role In CounTerIng Terrorism ii. enhanCe straTegic CommunicationS iii. deePen relationShips BeTween un head- quarTerS and national and regIonal parTnerS Iv. -

Federal Bureau of Investigation Department of Homeland Security

Federal Bureau of Investigation Department of Homeland Security Strategic Intelligence Assessment and Data on Domestic Terrorism Submitted to the Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence, the Committee on Homeland Security, and the Committee of the Judiciary of the United States House of Representatives, and the Select Committee on Intelligence, the Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, and the Committee of the Judiciary of the United States Senate May 2021 Page 1 of 40 Table of Contents I. Overview of Reporting Requirement ............................................................................................. 2 II. Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................... 2 III. Introduction...................................................................................................................................... 2 IV. Strategic Intelligence Assessment ................................................................................................... 5 V. Discussion and Comparison of Investigative Activities ................................................................ 9 VI. FBI Data on Domestic Terrorism ................................................................................................. 19 VII. Recommendations .......................................................................................................................... 27 Appendix .................................................................................................................................................... -

The Interim National Security Strategic Guidance

March 29, 2021 The Interim National Security Strategic Guidance On March 3, 2021, the White House released an Interim and what the right emphasis - in terms of budgets, priorities, National Security Strategic Guidance (INSSG). This is the and activities—ought to be between the different kinds of first time an administration has issued interim guidance; security challenges. The 2017 Trump Administration NSS previous administrations refrained from issuing formal framed the key U.S. national security challenge as one of guidance that articulated strategic intent until producing the strategic competition with other great powers, notably congressionally mandated National Security Strategy (NSS) China and Russia. While there were economic dimensions (originating in the Goldwater-Nichols Department of to this strategic competition, the 2017 NSS emphasized Defense Reorganization Act of 1986 P.L. 99-433, §603/50 American military power as a key part of its response to the U.S.C §3043). The full NSS is likely to be released later in challenge. 2021 or early 2022. By contrast, the Biden INSSG appears to invert traditional The INSSG states the Biden Administration’s conceptual national security strategy formulations, focusing on approach to national security matters as well as signaling its perceived shortcomings in domestic social and economic key priorities, particularly as executive branch departments policy rather than external threats as its analytic starting and agencies prepare their Fiscal Year (FY) 2022 budget point. The Biden Administration contends that the lines submissions. With respect to the latter, FY2022 will be the between foreign and domestic policy have been blurred to first budget prepared after the expiration of the budget caps the point of near nonexistence. -

Principles for Software Assurance Assessment a Framework for Examining the Secure Development Processes of Commercial Technology Providers

Principles for Software Assurance Assessment A Framework for Examining the Secure Development Processes of Commercial Technology Providers PRIMARY AUTHORS: Shaun Gilmore, Senior Security Program Manager, Trustworthy Computing, Microsoft Corporation Reeny Sondhi, Senior Director, Product Security Engineering, EMC Corporation Stacy Simpson, Director, SAFECode © 2015 SAFECode – All Rights Reserved. Principles for Software Assurance Assessment Table of Contents Foreword ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 3 Methodology �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 3 Problem Statement ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 4 Framework Overview ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 5 Guiding Principles for Software Security Assessment ����������������������������������������������������������������������6 The SAFECode Supplier Software Assurance Assessment Framework ������������������������������ 7 What Are Your Risk Management Requirements? ����������������������������������������������������������������������������7 The Tier Three Assessment �����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������8 The Tier One and Tier Two Assessments ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������8 -

Small Business Information Security: the Fundamentals

NISTIR 7621 Small Business Information Security: The Fundamentals Richard Kissel NISTIR 7621 Small Business Information Security: The Fundamentals Richard Kissel Computer Security Division Information Technology Laboratory National Institute of Standards and Technology Gaithersburg, MD 20899 October 2009 U.S. Department of Commerce Gary Locke, Secretary National Institute of Standards and Technology Patrick D. Gallagher, Deputy Director Acknowledgements The author, Richard Kissel, wishes to thank his colleagues and reviewers who contributed greatly to the document’s development. Special thanks goes to Mark Wilson, Shirley Radack, and Carolyn Schmidt for their insightful comments and suggestions. Kudos to Kevin Stine for his awesome Word editing skills. Certain commercial entities, equipment, or materials may be identified in this document in order to describe and experimental procedure or concept adequately. Such identification is not intended to imply recommendation or endorsement by the National Institute of Standards and Technology, nor is it intended to imply that the entities, materials, or equipment are necessarily the best available for the purpose. i Table of Contents Overview...................................................................................................................................................... 1 1. Introduction.......................................................................................................................................... 1 2. The “absolutely necessary” actions that a small -

An Introduction to Computer Security: the NIST Handbook U.S

HATl INST. OF STAND & TECH R.I.C. NIST PUBLICATIONS AlllOB SEDS3fl NIST Special Publication 800-12 An Introduction to Computer Security: The NIST Handbook U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Technology Administration National Institute of Standards Barbara Guttman and Edward A. Roback and Technology COMPUTER SECURITY Contingency Assurance User 1) Issues Planniii^ I&A Personnel Trairang f Access Risk Audit Planning ) Crypto \ Controls O Managen»nt U ^ J Support/-"^ Program Kiysfcal ~^Tiireats Policy & v_ Management Security Operations i QC 100 Nisr .U57 NO. 800-12 1995 The National Institute of Standards and Technology was established in 1988 by Congress to "assist industry in the development of technology . needed to improve product quality, to modernize manufacturing processes, to ensure product reliability . and to facilitate rapid commercialization ... of products based on new scientific discoveries." NIST, originally founded as the National Bureau of Standards in 1901, works to strengthen U.S. industry's competitiveness; advance science and engineering; and improve public health, safety, and the environment. One of the agency's basic functions is to develop, maintain, and retain custody of the national standards of measurement, and provide the means and methods for comparing standards used in science, engineering, manufacturing, commerce, industry, and education with the standards adopted or recognized by the Federal Government. As an agency of the U.S. Commerce Department's Technology Administration, NIST conducts basic and applied research in the physical sciences and engineering, and develops measurement techniques, test methods, standards, and related services. The Institute does generic and precompetitive work on new and advanced technologies. NIST's research facilities are located at Gaithersburg, MD 20899, and at Boulder, CO 80303. -

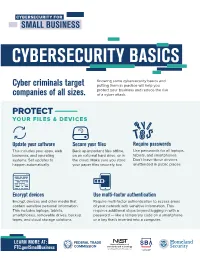

Cybersecurity Basics

CYBERSECURITY FOR SMALL BUSINESS CYBERSECURITY BASICS Knowing some cybersecurity basics and Cyber criminals target putting them in practice will help you protect your business and reduce the risk companies of all sizes. of a cyber attack. PROTECT YOUR FILES & DEVICES Update your software Secure your files Require passwords This includes your apps, web Back up important files offline, Use passwords for all laptops, browsers, and operating on an external hard drive, or in tablets, and smartphones. systems. Set updates to the cloud. Make sure you store Don’t leave these devices happen automatically. your paper files securely, too. unattended in public places. Encrypt devices Use multi-factor authentication Encrypt devices and other media that Require multi-factor authentication to access areas contain sensitive personal information. of your network with sensitive information. This This includes laptops, tablets, requires additional steps beyond logging in with a smartphones, removable drives, backup password — like a temporary code on a smartphone tapes, and cloud storage solutions. or a key that’s inserted into a computer. LEARN MORE AT: FTC.gov/SmallBusiness CYBERSECURITY FOR SMALL BUSINESS PROTECT YOUR WIRELESS NETWORK Secure your router Change the default name and password, turn off remote management, and log out as the administrator once the router is set up. Use at least WPA2 encryption Make sure your router offers WPA2 or WPA3 encryption, and that it’s turned on. Encryption protects information sent over your network so it can’t be read by outsiders. MAKE SMART SECURITY YOUR BUSINESS AS USUAL Require strong passwords Train all staff Have a plan A strong password is at least Create a culture of security Have a plan for saving data, 12 characters that are a mix of by implementing a regular running the business, and numbers, symbols, and capital schedule of employee training. -

The Basic Components of an Information Security Program MBA Residential Technology Forum (RESTECH) Information Security Workgroup

ONE VOICE. ONE VISION. ONE RESOURCE. The Basic Components of an Information Security Program MBA Residential Technology Forum (RESTECH) Information Security Workgroup 20944 MBA.ORG Copyright © October 2019 by Mortgage Bankers Association. All Rights Reserved. Copying, selling or otherwise distributing copies and / or creating derivative works for commercial purposes is strictly prohibited. Although significant efforts have been used in preparing this guide, MBA makes no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy and completeness of the contents. If legal advice or other expert assistance is needed, competent professionals should be consulted. Copying in whole or in part for internal business purposes and other non-commercial uses is permissible provided attribution to Mortgage Bankers Association is included, either through use of the previous paragraph (when copying / distributing the white paper in full) or the following (when distributing or including portions in a derivative work): “Source: Mortgage Bankers Association, The Basic Components of an Informa- tion Security Program, by the Information Security Work Group of the MBA Residential Technology Forum (RESTECH), 2019, [page(s)].” Table of Contents Preface . 1 1. Introduction . 2 2. Laws and Regulations for .Information . Security. 5 3. First Priority Cybersecurity Practices . .6 . 3.1 Manage Risk. .6 3.2 Protect your Endpoints . 6 3.3 Protect Your Internet . Connection. .7 3.4 Patch Your Operating Systems and Applications . 8 . 3.5 Make Backup Copies of Important Business. Data / Information. .8 3.6 Control Physical Access to Your Computers and Network Components . 9 . 3.7 Secure Your Wireless Access Points. .and . Networks. 10 3.8 Train Your Employees in Basic . -

Understanding the Emerging Era of International Competition Theoretical and Historical Perspectives

Research Report C O R P O R A T I O N MICHAEL J. MAZARR, JONATHAN BLAKE, ABIGAIL CASEY, TIM MCDONALD, STEPHANIE PEZARD, MICHAEL SPIRTAS Understanding the Emerging Era of International Competition Theoretical and Historical Perspectives he most recent U.S. National Security KEY FINDINGS Strategy is built around the expectation ■ The emerging competition is not generalized but likely to of a new era of intensifying international be most intense between a handful of specific states. Tcompetition, characterized by “growing political, economic, and military competitions” ■ The hinge point of the competition will be the relation- confronting the United States.1 The new U.S. ship between the architect of the rules-based order (the United States) and the leading revisionist peer competitor National Defense Strategy is even more blunt that is involved in the most specific disputes (China). about the nature of the emerging competition. “We are facing increased global disorder, ■ Global patterns of competition are likely to be complex and diverse, with distinct types of competition prevailing characterized by decline in the long-standing 2 in different issue areas. rules-based international order,” it argues. “Inter-state strategic competition, not terrorism, ■ Managing the escalation of regional rivalries and conflicts is now the primary concern in U.S. national is likely to be a major focus of U.S. statecraft. security.”3 The document points to the ■ Currently, the competition seems largely focused on “reemergence of long-term, strategic competition status grievances or ambitions, economic prosperity, by what the National Security Strategy classifies technological advantage, and regional influence. as revisionist powers.”4 It identifies two ■ The competition is likely to be most intense and per- countries as potential rivals: China and Russia.