What Is Artistic Freedom?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

January TK, 2016

January 15, 2016 Ayatollah Sadeq Larijani Office of the Head of the Judiciary Via the Interests Section of the Islamic Republic of Iran ([email protected]) Dear Ayatollah Sadeq Larijani, Iran has an ancient, globally recognised culture and has over centuries produced excellent artists of world standard. Artists are carriers of tradition, but often break new ground essential to the development of a society. We are writing to express our concern about the imprisonment in 2013 and sentencing in 2015 of musicians Mehdi Rajabian and Yousef Emadi and filmmaker Hossein Rajabian who were jointly sentenced to six years in prison and fined 200 million tomans each for “insulting the sacred” and “propaganda against the state”. Mehdi Rajabian, a musician and founder of BargMusic, an alternative music distributor in Iran, along with his filmmaker brother Hossein Rajabian and musician Emadi, appeared at Branch 54 of the Tehran Province Appeals Court on 22 December 2015. A decision on the appeal is expected in the coming days. During the appeal hearing, the judge admonished the artists for ignoring repeated warnings that they were operating illegally and had ties with Iranian singers abroad opposed to the Islamic Republic. Since the establishment of the Islamic Republic, Iranian musicians have needed government authorization in order to hold concerts and produce music albums and videos. Government scrutiny is stringent and only certain genres of music receive licenses. Even when musicians are issued concert licenses there is no guarantee they can safely hold their scheduled appearances. It is within this context that the BargMusic website, established by Mehdi Rajabian in 2009, became a portal for distributing Iranian alternative music. -

2016 Case List

FRONT COVER 1 3 PEN INTERNATIONAL CHARTER The PEN Charter is based on resolutions passed at its International Congresses and may be summarised as follows: PEN affirms that: 1. Literature knows no frontiers and must remain common currency among people in spite of political or international upheavals. 2. In all circumstances, and particularly in time of war, works of art, the patrimony of humanity at large, should be left untouched by national or political passion. 3. Members of PEN should at all times use what influence they have in favour of good understanding and mutual respect between nations; they pledge themselves to do their utmost to dispel race, class and national hatreds, and to champion the ideal of one humanity living in peace in one world. 4. PEN stands for the principle of unhampered transmission of thought within each nation and between all nations, and members pledge themselves to oppose any form of suppression of freedom of expression in the country and community to which they belong, as well as throughout the world wherever this is possible. PEN declares for a free press and opposes arbitrary censorship in time of peace. It believes that the necessary advance of the world towards a more highly organised political and economic order renders a free criticism of governments, administrations and institutions imperative. And since freedom implies voluntary restraint, members pledge themselves to oppose such evils of a free press as mendacious publication, deliberate falsehood and distortion of facts for political and personal ends. Membership of PEN is open to all qualified writers, editors and translators who subscribe to these aims, without regard to nationality, ethnic origin, language, colour or religion. -

The Arts Politic Issue 2

THE ARTS POLITIC ISSUE : BIAS | SPRING EDITOR Jasmine Jamillah Mahmoud EXECUTIVE EDITOR Danielle Kline CREATIVE DIRECTOR Kemeya Harper CULTURE EDITOR RonAmber Deloney 15 COLUMNISTS RonAmber Deloney and Brandon Woolf CONTRIBUTING WRITERS & ARTISTS Melanie Cervantes, Edward P. Clapp, Rhoda Draws, Amelia Edelman, Shanthony Exum, Rachel Falcone, Arlene Goldbard, Robert A. K. Gonyo, Malvika Maheshwari, Ashley Marinaccio, Gisele Morey, Michael Premo, Bridgette Raitz, Betty Lark Ross, RVLTN, Gregory Sholette and Wendy Testu. CONTRIBUTING VOICES Chris Appleton, Sally Baghsaw, Phillip Bimstein, Joshua Clover, Dan Cowan, Maria Dumlao, Kevin Erickson, Elizabeth Glidden, Joe Goode, Art Hazelwood, Elaine Kaufmann, Danielle Mysliwiec, Judy Nemzoff, Anne Polashenski, Garey Lee Posey, Kevin Postupack, Gregory Sholette, Manon Slome and Robynn Takayama. FOUNDING EDITORS Danielle Evelyn Kline & Jasmine Jamillah Mahmoud SPECIAL THANKS Department of Art and Public Policy at Tisch School of the Arts, NYU 31 THE ARTS POLITIC is a print-and-online magazine dedicated to solving problems at the intersection of arts and politics. Cultural policy, arts activism, political art, the creative economy—THE ARTS 12 POLITIC creates a conversation amongst leaders, activists, and idea-makers along the pendulum of global civic responsibility. A forum for creative and political thinking, a stage for emerging art, and a platform for social change, THE ARTS POLITIC provides a space that is intelligent, that is visionary, that is thoughtful, that will TAP new ideas from the frontlines to get things done. Copyright ©2010 by THE ARTS POLITIC. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part without permission is prohibited. If you would like to order the print edition and/or subscribe to the online edition, please visit: theartspolitic.com/subscribe. -

9 June–21 June 2015 Talks/Exhibitions/Theatre/Music/Film Yorkfestivalofideas.Com

9 June–21 June 2015 Talks/Exhibitions/Theatre/Music/Film yorkfestivalofideas.com Preview From Friday 29 May look out for the special preview events including Michael Morpurgo, Goalball and Science out of the Lab YORK FESTIVAL OF IDEAS 2015 HEADLINE SPONSOR As a continuing Headline Sponsor, The Holbeck Charitable Trust is delighted to see York Festival of Ideas go from strength to strength. The programme for 2015 offers a stimulating and diverse series of events, workshops, talks, performances and exhibitions. We applaud the Festival’s determination to remain as widely accessible as practicable by staging so many events where entry is free. We are proud to support the team’s ambition to develop a festival which, in time, should become a mainstay of the national cultural calendar. 2 yorkfestivalofideas.com York Festival of Ideas 2015 Contents EXPLORING IDEAS OF Calendar of events 4 SECRETS AND DISCOVERIES Festival launch 10 FESTIVAL THEMES Curiouser and Curiouser 11 Welcome to the world of ‘Secrets and doing so we are stronger and more captivating. Discovering York 16 The Art of Communication 20 Discoveries’ seen through the lens of York Most of all we believe that we are a more Festival of Ideas. A world where audiences of compelling festival because our audiences are Science out of the Lab 24 all ages and interests can participate in over driven by an innate sense of curiosity. It is Revealing the Ancient World 26 100 free events encompassing art and design, notable that every year high-profile speakers, Eoforwic 28 the economy and equality, food and health, who regularly speak at international festivals, Behind the Lens 34 performance and poetry, the past and the comment on the originality and intelligence of Hidden Histories 36 future, security and surveillance, truth and the questions they are asked by York Festival of Culture and Identity 40 trust, technology and the environment, and Ideas audiences. -

Defending the Right to Freedom of Artistic Expression

Defending the Right to Freedom of Artistic Expression K. Bennoune, Special Rapporteur in the field of cultural rights Art-at-risk conference, Zürich, Switzerland 28 February 2020 Good evening. It is a real pleasure to be here with you at this important gathering with artists and defenders of artistic freedom from Switzerland and from all over the world. I’d like to thank the organizers for this very special convening, and also for inviting me. I realize that I stand between you and your Friday evening at the end of many rich discussions so I thank you sincerely for your attention. This evening, I am going to talk about defending the right to artistic freedom within the broader context of defending cultural rights as a whole, drawing from my report on Cultural Rights Defenders to be presented to the UN Human Rights Council on Tuesday March 3.1 I will share some of the ideas in this report. Let me express my sincere gratitude to those in this room from different regions who made contributions to the report which greatly enriched it. The main point I wish to make this evening is that if the international community values artistic freedom, it must find ways to better support and enable the work of those who defend that human right. It must also respect and ensure their human rights. I start with a personal anecdote. Last Sunday I was very stressed about getting ready for this trip. So I decided that I needed a culture cure. I spent the afternoon in the San Francisco area with cultural rights defenders. -

Religious Leaders in Politics

International Journal of Latin American Religions https://doi.org/10.1007/s41603-020-00123-1 THEMATIC PAPERS Open Access Religious Leaders in Politics: Rio de Janeiro Under the Mayor-Bishop in the Times of the Pandemic Liderança religiosa na política: Rio de Janeiro do bispo-prefeito nos tempos da pandemia Renata Siuda-Ambroziak1,2 & Joana Bahia2 Received: 21 September 2020 /Accepted: 24 September 2020/ # The Author(s) 2020 Abstract The authors discuss the phenomenon of religious and political leadership focusing on Bishop Marcelo Crivella from the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God (IURD), the current mayor of the city of Rio de Janeiro, in the context of the political involvement of his religious institution and the beginnings of the COVID-19 pandemic. In the article, selected concepts of leadership are applied in the background of the theories of a religious field, existential security, and the market theory of religion, to analyze the case of the IURD leadership political involvement and bishop/mayor Crivella’s city management before and during the pandemic, in order to show how his office constitutes an important part of the strategies of growth implemented by the IURD charismatic leader Edir Macedo, the founder and the head of this religious institution and, at the same time, Crivella’s uncle. The authors prove how Crivella’s policies mingle the religious and the political according to Macedo’s political alliances at the federal level, in order to strengthen the church and assure its political influence. Keywords Religion . Politics . Leadership . Rio de Janeiro . COVID-19 . Pandemic Palavras-chave Religião . -

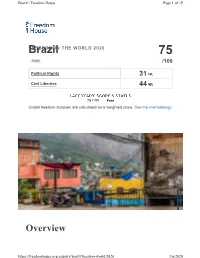

Freedom in the World Report 2020

Brazil | Freedom House Page 1 of 19 BrazilFREEDOM IN THE WORLD 2020 75 FREE /100 Political Rights 31 Civil Liberties 44 75 Free Global freedom statuses are calculated on a weighted scale. See the methodology. Overview https://freedomhouse.org/country/brazil/freedom-world/2020 3/6/2020 Brazil | Freedom House Page 2 of 19 Brazil is a democracy that holds competitive elections, and the political arena is characterized by vibrant public debate. However, independent journalists and civil society activists risk harassment and violent attack, and the government has struggled to address high rates of violent crime and disproportionate violence against and economic exclusion of minorities. Corruption is endemic at top levels, contributing to widespread disillusionment with traditional political parties. Societal discrimination and violence against LGBT+ people remains a serious problem. Key Developments in 2019 • In June, revelations emerged that Justice Minister Sérgio Moro, when he had served as a judge, colluded with federal prosecutors by offered advice on how to handle the corruption case against former president Luiz Inácio “Lula” da Silva, who was convicted of those charges in 2017. The Supreme Court later ruled that defendants could only be imprisoned after all appeals to higher courts had been exhausted, paving the way for Lula’s release from detention in November. • The legislature’s approval of a major pension reform in the fall marked a victory for Brazil’s far-right president, Jair Bolsonaro, who was inaugurated in January after winning the 2018 election. It also signaled a return to the business of governing, following a period in which the executive and legislative branches were preoccupied with major corruption scandals and an impeachment process. -

The State of Artistic Freedom 2021

THE STATE OF ARTISTIC FREEDOM 2021 THE STATE OF ARTISTIC FREEDOM 2021 1 Freemuse (freemuse.org) is an independent international non-governmental organisation advocating for freedom of artistic expression and cultural diversity. Freemuse has United Nations Special Consultative Status to the Economic and Social Council (UN-ECOSOC) and Consultative Status with UNESCO. Freemuse operates within an international human rights and legal framework which upholds the principles of accountability, participation, equality, non-discrimination and cultural diversity. We document violations of artistic freedom and leverage evidence-based advocacy at international, regional and national levels for better protection of all people, including those at risk. We promote safe and enabling environments for artistic creativity and recognise the value that art and culture bring to society. Working with artists, art and cultural organisations, activists and partners in the global south and north, we campaign for and support individual artists with a focus on artists targeted for their gender, race or sexual orientation. We initiate, grow and support locally owned networks of artists and cultural workers so their voices can be heard and their capacity to monitor and defend artistic freedom is strengthened. ©2021 Freemuse. All rights reserved. Design and illustration: KOPA Graphic Design Studio Author: Freemuse Freemuse thanks those who spoke to us for this report, especially the artists who took risks to take part in this research. We also thank everyone who stands up for the human right to artistic freedom. Every effort has been made to verify the accuracy of the information contained in this report. All information was believed to be correct as of February 2021. -

No. 233, 26 Juillet 2009

Observatory of Cultural Policies in Africa The Observatory is a Pan African international NGO created in 2002 with the support of African Union, the Ford Foundation, and UNESCO. Its aim is to monitor cultural trends and national cultural policies in the region and to enhance their integration in human development strategies through advocacy, information, research, capacity building, networking, co-ordination, and co- operation at the regional and international levels. O C P A OCPA NEWS N° 233 26 July 2009 Published with the support of the Spanish Agency for International Co- operation for Development (AECID) This issue is sent to 8485 addresses * VISIT THE OCPA WEB SITE http://www.ocpanet.org * We wish to promote interactive information exchange within Africa and between Africa and the other regions. Please send us information for dissemination about new initiatives, meetings, research projects and publications of interest for cultural policies for development in Africa. Thank you for your co-operation. * Nous souhaitons promouvoir un échange d’information interactif en Afrique ainsi qu’entre l’Afrique et les autres régions. Envoyez-nous des informations pour diffusion sur des initiatives novelles, réunions, projets de recherches, publications intéressant les politiques culturelles pour le développement en Afrique. Merci de votre coopération. Máté Kovács, editor: [email protected] *** Contact: OCPA Secretariat, 725, Avenida da Base N'Tchinga, P. O. Box 1207 Maputo, Mozambique Tel: +258- 21- 41 86 49, Fax: +258- 21- 41 86 50 E-mail: [email protected] or Executive Director: Lupwishi Mbuyamba: [email protected] You can subscribe or unsubscribe to OCPA News via the online form at http://ocpa.irmo.hr/activities/newsletter/index-en.html. -

Human Rights for Musicians Freemuse

HUMAN RIGHTS FOR MUSICIANS FREEMUSE – The World Forum on Music and Censorship Freemuse is an international organisation advocating freedom of expression for musicians and composers worldwide. OUR MAIN OBJECTIVES ARE TO: • Document violations • Inform media and the public • Describe the mechanisms of censorship • Support censored musicians and composers • Develop a global support network FREEMUSE Freemuse Tel: +45 33 32 10 27 Nytorv 17, 3rd floor Fax: +45 33 32 10 45 DK-1450 Copenhagen K Denmark [email protected] www.freemuse.org HUMAN RIGHTS FOR MUSICIANS HUMAN RIGHTS FOR MUSICIANS Ten Years with Freemuse Human Rights for Musicians: Ten Years with Freemuse Edited by Krister Malm ISBN 978-87-988163-2-4 Published by Freemuse, Nytorv 17, 1450 Copenhagen, Denmark www.freemuse.org Printed by Handy-Print, Denmark © Freemuse, 2008 Layout by Kristina Funkeson Photos courtesy of Anna Schori (p. 26), Ole Reitov (p. 28 & p. 64), Andy Rice (p. 32), Marie Korpe (p. 40) & Mik Aidt (p. 66). The remaining photos are artist press photos. Proofreading by Julian Isherwood Supervision of production by Marie Korpe All rights reserved CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Human rights for musicians – The Freemuse story Marie Korpe 9 Ten years of Freemuse – A view from the chair Martin Cloonan 13 PART I Impressions & Descriptions Deeyah 21 Marcel Khalife 25 Roger Lucey 27 Ferhat Tunç 29 Farhad Darya 31 Gorki Aguila 33 Mahsa Vahdat 35 Stephan Said 37 Salman Ahmad 41 PART II Interactions & Reactions Introducing Freemuse Krister Malm 45 The organisation that was missing Morten -

November 28, 2016 URGENT APPEAL Mónica

Honorary Co-Chairs The Most Reverend Desmond M. Tutu President Mohamed Nasheed November 28, 2016 URGENT APPEAL Mónica Pinto Special Rapporteur on the Independence of Judges and Lawyers Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights United Nations Office at Geneva 8-14 Avenue de la Paix 1211 Geneva 10, Switzerland Re: Urgent Appeal Regarding Mohammed Shaikh Ould Mohammed Ould Mkhaitir Dear Ms. Pinto: We request urgent action from your office regarding the pending appeal of Mr. Mohammed Shaikh Ould Mohammed Ould Mkhaitir in the Islamic Republic of Mauritania, where Mr. Mkhaitir is sentenced to execution for alleged crimes involving the exercise of his freedom of expression. Mr. Mkhaitir was initially convicted of hypocrisy and remains in prison for authoring a critique which challenged the social and religious underpinnings of modern-day slavery. Mr. Mkhaitir is currently awaiting a final verdict from the Supreme Court of Mauritania. Throughout the entirety of Mr. Mkhaitir’s proceedings, the independence and non-partiality of the courts have come into question and recent events have shown that the Mauritanian Supreme Court is under extreme pressure to uphold Mr. Mkhaitir’s death sentence. Mr. Mkhaitir’s appeal to the Mauritanian Supreme Court was heard on November 15, 2016. Two days prior, the Forum of Imams and Ulema issued a fatwa demanding that the death sentence be carried out: “Kill him and bury him in conformity with the law of God.” On the day of the appeal, thousands of people gathered outside the courthouse to demand Mr. Mkhaitir’s execution. Fearing for its own safety as well as the safety of the parties and counsel, the Supreme Court delayed the verdict and will reconvene on December 20, 2016. -

Celebrating the World Day for Cultural Diversity

CELEBRATING THE WORLD DAY FOR CULTURAL DIVERSITY INVESTING IN CREATIVITY The UNESCO 2005 Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions Reiko Yoshida UNESCO Cultural and Creative Industries (CCIs) 2005 Convention The UNESCO 2005 Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions a legally-binding international agreement establishes the right to adopt policies and measures to support the emergence of dynamic and strong cultural and creative 149 industries Parties to the ensures artists, cultural professionals, Convention practitioners and citizens worldwide can create, produce, disseminate and enjoy a broad range of cultural goods, services and activities, including their own a tool to reinforce organizational structures that have a direct impact on the different stages of the cultural value 2005 Convention Monitoring Framework THE 2005 CONVENTION AT WORK Goal 1 The 2005 Convention assists governments in the design and implementation of policies that support creation, production, distribution and access to diverse cultural goods and services, These policies must be: transparent in their decision making processes participatory by engaging civil society in policy design and implementation informed through the regular collection of evidence and data to support future policy decisions SUPPORTING CREATIVITY Digital Age IN THE DIGITAL AGE Goal 2 The 2005 Convention orients governments in designing policies and measure that ensure equitable access, openness and balance. These policies and measures must ensure that: Creative professionals and artists can travel freely Balance in the flow of cultural goods and services is achieved Preferential treatment measures, such as new trade frameworks and agreements, recognize the specificity of cultural goods and services Global Marketplace PUTTING PREFERENTIAL TREATMENT INTO PRACTICE Goal 3 The 2005 Convention supports governments in the integration of culture in their sustainable development policies, plans and programmes.