Most Corrupt: Representative Maxine Waters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Impeachment of Donald J. Trump, President of the United States: Report of the Comm

IN THE SENATEOF THEUNITED STATES Sitting as a Court of Impeachment Inre IMPEACHMENTOF PRESIDENT DONALD J. TRUMP TRIAL MEMORANDUM OF THEUNITEDSTATES HOUSEOF REPRESENTATIVES IN THE IMPEACHMENTTRIALOF PRESIDENT DONALD J. TRUMP United States House of Representatives AdamB.Schiff JerroldNadler Zoe Lofgren HakeemS.Jeffries Val ButlerDemings Jason Crow Sylvia R.Garcia U.S. House of RepresentativesManagers TABLEOF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION...........................................................................................................................................1 BACKGROUND..............................................................................................................................................9 I. C ONSTITUTIONALG ROUNDSFORP RESIDENTIALI MPEACHMENT....................................................9 II. THE HOUSE’SIMPEACHMENTOF PRESIDENTDONALDJ. TRUMPANDPRESENTATIONOF T HISM ATTERTO THE S ENATE..............................................................................................................12 ARGUMENT...................................................................................................................................................16 I. T HE S ENATES HOULDC ONVICT P RESIDENTT RUMPOF A BUSEOF P OWER..................................16 A. PresidentTrumpExercisedHis OfficialPowerto PressureUkraineintoAidingHis Reelection....................................................................................................................................16 B. PresidentTrumpExercisedOfficialPowerto -

The Honorable Nancy Pelosi the Honorable Maxine Waters Speaker

The Honorable Nancy Pelosi The Honorable Maxine Waters Speaker of the House Chair, House Financial Services Committee H-232 The Capitol 2221 Rayburn House Office Building Washington, D.C. 20510 Washington, D.C. 20515 RE: SUPPORT – California CDFIs Support $1 Billion for the CDFI Fund in Phase 4 Relief Package On behalf of 38 California Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs) we write to express our support for Chairwoman Waters’ recent proposal to include $1 billion for the CDFI Fund highlighted in her recent “Proposed Package 4 Related to COVID-19.” The California Coalition for Community Investment (CCCI) is a coalition of almost 40 CDFIs doing business across the state. The coalition consists of affordable housing lenders, small business lenders, microlenders, credit unions and housing trust funds dedicated to supporting California’s most vulnerable communities. The mission is to provide these CDFIs appropriate resources to do what they do best. CDFIs understand and can respond quickly to the needs of their consumers, housing developers and small business owners and are uniquely positioned to respond to relief and recovery during this crisis. CDFIs fill a vital gap in the nation's financial services delivery system through their strong expertise and deep community relationships. CDFIs have proven success addressing their communities’ needs during both natural and national disasters. During the Great Recession, when mainstream finance retracted lending, CDFIs kept capital flowing to businesses and communities. In 2017, when California was devastated by a series of wildfires in the North Bay and in Ventura County, CDFIs responded. In 2018, when the Camp Fire destroyed almost 19,000 homes, businesses and other structures, CDFIs responded. -

STANDING COMMITTEES of the HOUSE Agriculture

STANDING COMMITTEES OF THE HOUSE [Democrats in roman; Republicans in italic; Resident Commissioner and Delegates in boldface] [Room numbers beginning with H are in the Capitol, with CHOB in the Cannon House Office Building, with LHOB in the Longworth House Office Building, with RHOB in the Rayburn House Office Building, with H1 in O’Neill House Office Building, and with H2 in the Ford House Office Building] Agriculture 1301 Longworth House Office Building, phone 225–2171, fax 225–8510 http://agriculture.house.gov meets first Wednesday of each month Collin C. Peterson, of Minnesota, Chair Tim Holden, of Pennsylvania. Bob Goodlatte, of Virginia. Mike McIntyre, of North Carolina. Terry Everett, of Alabama. Bob Etheridge, of North Carolina. Frank D. Lucas, of Oklahoma. Leonard L. Boswell, of Iowa. Jerry Moran, of Kansas. Joe Baca, of California. Robin Hayes, of North Carolina. Dennis A. Cardoza, of California. Timothy V. Johnson, of Illinois. David Scott, of Georgia. Sam Graves, of Missouri. Jim Marshall, of Georgia. Jo Bonner, of Alabama. Stephanie Herseth Sandlin, of South Dakota. Mike Rogers, of Alabama. Henry Cuellar, of Texas. Steve King, of Iowa. Jim Costa, of California. Marilyn N. Musgrave, of Colorado. John T. Salazar, of Colorado. Randy Neugebauer, of Texas. Brad Ellsworth, of Indiana. Charles W. Boustany, Jr., of Louisiana. Nancy E. Boyda, of Kansas. John R. ‘‘Randy’’ Kuhl, Jr., of New York. Zachary T. Space, of Ohio. Virginia Foxx, of North Carolina. Timothy J. Walz, of Minnesota. K. Michael Conaway, of Texas. Kirsten E. Gillibrand, of New York. Jeff Fortenberry, of Nebraska. Steve Kagen, of Wisconsin. Jean Schmidt, of Ohio. -

Sponsorship Opportunities Sponsorship Opportunities We Are Global Leaders

SPONSORSHIP OPPORTUNITIES SPONSORSHIP OPPORTUNITIES WE ARE GLOBAL LEADERS CBCF Vision: We envision a world in which all communities have an equal voice in public policy through leadership cultivation, economic empowerment, and civic engagement. SCHOLARSHIP CLASSIC 2020 CBCFINC.ORG // 2 CONGRESSIONAL BLACK CAUCUS NATIONAL LEADERSHIP CBC MEMBERS IN LEADERSHIP HOUSE EXECUTIVE LEADERSHIP 116TH CONGRESS COMMITTEE CHAIRS 4 Rep. James E. Clyburn Rep. Maxine Waters Majority Whip House Financial Services Committee Rep. Karen Bass Rep. Cedric L. Chair, CBC Richmond Rep. Bobby Scott CBCF Chair, Board of Education and the Workforce Directors Committee Rep. Hakeem Jeffries Democratic Caucus Chairman SENATORS IN THE CBC Rep. Bennie Thompson Homeland Security Rep. Barbara Lee Rep. Eddie Bernice Johnson Co-chair, Steering and Policy Science, Space and Technology Committee Sen. Cory Booker Sen. Kamala D. Harris HOUSE SUBCOMMITTEE CHAIRS 28 SCHOLARSHIP CLASSIC 2020 CBCFINC.ORG // 3 CONGRESSIONAL BLACK CAUCUS NATIONAL REACH Representing more than 82 MILLION Americans in 26 States & 1 Territory 41% of the total U.S. African American population 25% of the total CBC Member U.S. population States/Territory 54 49 MEMBERS YEARS OF EMPOWERMENT SCHOLARSHIP CLASSIC 2020 CBCFINC.ORG // 4 WE ARE CHANGING THE WORLD CBCF Mission: The Congressional Black Caucus Foundation, Inc. works to advance the global black community by developing leaders, informing policy, and educating the public. SCHOLARSHIP CLASSIC 2020 CBCFINC.ORG // 5 LUXURIOUS LOCATION This year’s Scholarship Classic will be hosted at the luxurious Hyatt Regency Chesapeake Bay Golf Resort, Spa and Marina in Cambridge, Maryland. SCHOLARSHIP CLASSIC 2020 CBCFINC.ORG // 6 IDEAS & DEVELOPING INFORMATION LEADERS Facilitating the exchange Providing leadership OUR WORK of ideas and information development and to address critical issues scholarship opportunities to TO ACHIEVE affecting our community. -

Committee Tax” How the Parties Pressured Legislative Leaders to Raise Huge Sums of Campaign Cash During the 116Th Congress — and Are Poised to Do So Again This Year

New Congress, Same “Committee Tax” How the parties pressured legislative leaders to raise huge sums of campaign cash during the 116th Congress — and are poised to do so again this year By Amisa Ratliff One of the open secrets of Washington is that both the Democratic and Republican parties strong-arm influential legislators to raise astronomical amounts of campaign cash. Referred to as paying “party dues,” lawmakers are pressured to transfer huge sums from their campaigns and affiliated PACs to the parties as well as spend countless hours “dialing for dollars” to raise six- and seven-figure amounts for the parties, often by soliciting corporations, labor unions, and other special interests that have business before Congress. These fundraising demands have morphed into a “committee tax” levied Approximately $1 of by the political parties onto legislators. The more influential the role in every $5 spent during Congress, the more money party leaders expect legislators to raise, with the last election cycle by committee chairs being expected to raise more funds than other members several top Democratic of their caucus. This is especially true for the chairs of the most powerful and Republican committees in the U.S. House of Representatives — the Appropriations, lawmakers were simply Energy and Commerce, Financial Services, and Ways and Means Committees, transfers to the DCCC which are sometimes referred to as “A” committees for their prestige and and NRCC. influence. In fact, according to a new analysis of campaign finance filings by Issue One, approximately $1 of every $5 spent during the 2019-2020 election cycle by several of the top Democratic and Republican lawmakers on these exclusive “A” committees were simply transfers to the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee (DCCC) and National Republican Congressional Committee (NRCC). -

Congressional Directory CALIFORNIA

22 Congressional Directory CALIFORNIA Office Listings http://www.house.gov/woolsey 2263 Rayburn House Office Building, Washington, DC 20515 ................................. (202) 225–5161 Chief of Staff.—Nora Matus. FAX: 225–5163 Press Secretary.—Christopher Shields. 1101 College Avenue, Suite 200, Santa Rosa, CA 95404 .......................................... (707) 542–7182 District Director.—Wendy Friefeld. 1050 Northgate Drive, Suite 354, San Rafael, CA 94903 .......................................... (415) 507–9554 Counties: MARIN, SONOMA (part). CITIES AND TOWNSHIPS: Santa Rosa, Sebastapol, Cotati, Petaluma, and Sonoma to Golden Gate Bridge. Population (2000), 639,087. ZIP Codes: 94901, 94903–04, 94912–15, 94920, 94922–31, 94933, 94937–42, 94945–57, 94960, 94963–66, 94970–79, 94998–99, 95401–07, 95409, 95412, 95419, 95421, 95430–31, 95436, 95439, 95441–42, 95444, 95446, 95448, 95450, 95452, 95462, 95465, 95471–73, 95476, 95480, 95486, 95492, 95497 *** SEVENTH DISTRICT GEORGE MILLER, Democrat, of Martinez, CA; born in Richmond, CA, May 17, 1945; edu- cation: attended Martinez public schools; Diablo Valley College; graduated, San Francisco State College, 1968; J.D., University of California at Davis School of Law, 1972; member: California State bar; Davis Law School Alumni Association; served five years as legislative aide to Senate majority leader, California State Legislature; past chairman and member of Contra Costa County Democratic Central Committee; past president of Martinez Democratic Club; married: the for- mer Cynthia Caccavo; children: George and Stephen; four grandchildren; committees: chair, Education and Labor; Natural Resources; elected to the 94th Congress, November 5, 1974; reelected to each succeeding Congress. Office Listings http://www.house.gov/georgemiller [email protected] 2205 Rayburn House Office Building, Washington, DC 20515 ................................ -

August 10, 2021 the Honorable Nancy Pelosi the Honorable Steny

August 10, 2021 The Honorable Nancy Pelosi The Honorable Steny Hoyer Speaker Majority Leader U.S. House of Representatives U.S. House of Representatives Washington, D.C. 20515 Washington, D.C. 20515 Dear Speaker Pelosi and Leader Hoyer, As we advance legislation to rebuild and renew America’s infrastructure, we encourage you to continue your commitment to combating the climate crisis by including critical clean energy, energy efficiency, and clean transportation tax incentives in the upcoming infrastructure package. These incentives will play a critical role in America’s economic recovery, alleviate some of the pollution impacts that have been borne by disadvantaged communities, and help the country build back better and cleaner. The clean energy sector was projected to add 175,000 jobs in 2020 but the COVID-19 pandemic upended the industry and roughly 300,000 clean energy workers were still out of work in the beginning of 2021.1 Clean energy, energy efficiency, and clean transportation tax incentives are an important part of bringing these workers back. It is critical that these policies support strong labor standards and domestic manufacturing. The importance of clean energy tax policy is made even more apparent and urgent with record- high temperatures in the Pacific Northwest, unprecedented drought across the West, and the impacts of tropical storms felt up and down the East Coast. We ask that the infrastructure package prioritize inclusion of a stable, predictable, and long-term tax platform that: Provides long-term extensions and expansions to the Production Tax Credit and Investment Tax Credit to meet President Biden’s goal of a carbon pollution-free power sector by 2035; Extends and modernizes tax incentives for commercial and residential energy efficiency improvements and residential electrification; Extends and modifies incentives for clean transportation options and alternative fuel infrastructure; and Supports domestic clean energy, energy efficiency, and clean transportation manufacturing. -

The Honorable Nancy Pelosi the Honorable Mitch Mcconnell Speaker Majority Leader United States House of Representatives United

The Honorable Nancy Pelosi The Honorable Mitch McConnell Speaker Majority Leader United States House of Representatives United States Senate 1236 Longworth House Office Building 317 Russell Senate Office Building Washington, DC 20515 Washington, DC 20510 The Honorable Kevin McCarthy The Honorable Chuck Schumer Minority Leader Minority Leader United States House of Representatives United States Senate 2468 Rayburn House Office Building 322 Hart Senate Office Building Washington, DC 20515 Washington, DC 20510 Dear Speaker Pelosi, Majority Leader McConnell, Leader McCarthy and Leader Schumer: We write to express our deep concern and objection to the use of federal forces in U.S. cities. These forces are conducting crowd control on city streets and detaining individuals. Their threats and actions have as escalated events, and increased the risk of violence against both civilians and local law enforcement officers. These actions also jeopardize the many important ways federal and local law enforcement must work together to protect our cities and country. We urge you to immediately investigate the President and his administration’s actions. The unilateral deployment of these forces into American cities is unprecedented and violates fundamental constitutional protections and tenets of federalism. As you are well aware, President Trump threatened to deploy federal forces in Seattle to “clear out” a protest area and in Chicago to “clean up” the city. Seattle and Chicago authorities objected and threatened legal action to stop such actions. In Washington, DC outside Lafayette Park, extreme action was taken by federal law enforcement against protesters without the Mayor of DC’s approval. Now the administration has deployed federal forces to Portland despite the objections of local and state officials. -

115Th Congress

CALIFORNIA 115th Congress 39 gress on November 3, 1992 to the 103rd Congress; the first woman to serve as the chair of the California Democratic Congressional Delegation in the 105th Congress; in the 106th Con- gress, she became the first woman to chair the Congressional Hispanic Caucus, and the first Latina in history to be appointed to the House Appropriations Committee; in the 114th Con- gress, she became the first Latina to serve as Ranking Member of a House Appropriations sub- committee; married: Edward T. Allard III; two children: Lisa Marie and Ricardo; two step- children: Angela and Guy Mark; committees: Appropriations; elected to the 103rd Congress; reelected to each succeeding Congress. Office Listings http://www.roybal-allard.house.gov https://twitter.com/reproybalallard https://www.facebook.com/reproybalallard 2083 Rayburn House Office Building, Washington, DC 20515–0534 ..................................... (202) 225–1766 Chief of Staff.—Victor G. Castillo. FAX: 226–0350 Legislative Director.—Joseph Racalto. Executive Assistant.—Christine C. Ochoa. 500 Citadel Drive, Suite 320, Commerce, CA 90040–1572 ..................................................... (323) 721–8790 District Director.—Ana Figueroa. FAX: 721–8789 Counties: LOS ANGELES COUNTY (part). CITIES: Bell Gardens, Bellflower, Bill, Commerce, Cudahy, Downey, East Los Angeles, Florence-Graham, Huntington Park, Maywood, Paramount, South Los Angeles, Vernon, and Walnut Park. Population (2010), 694,514. ZIP Codes: 90001, 90003, 90007, 90011, 90015, 90021–23, 90037, 90040, 90052, 90058–59, 90063, 90082, 90091, 90201– 02, 90239–42, 90255, 90270, 90280, 90640, 90650, 90660, 90706, 90723, 91754 *** FORTY-FIRST DISTRICT MARK TAKANO, Democrat, of Riverside, CA; born in Riverside, December 10, 1960; edu- cation: B.A. -

Congress of the United States

ZOE LOFGREN, CALIFORNIA RODNEY DAVIS, ILLINOIS CHAIRPERSON RANKING MINORITY MEMBER Congress of the United States House of Representatives COMMITTEE ON HOUSE ADMINISTRATION 1309 Longworth House Office Building Washington, D.C. 20515-6157 (202) 225-2061 https://cha.house.gov March 19, 2021 The Honorable Zoe Lofgren Chairperson Committee on House Administration 1309 Longworth House Office Building Washington, DC 20515 Dear Chairperson Lofgren: At our most recent business meeting, you stated that the American people deserve a transparent, fair, and nonpartisan resolution of the nation’s elections. We agree. In order for us to conduct a fair and nonpartisan process, we must hold ourselves to the highest standards of ethical conduct as we continue proceedings to consider the election contests before our Committee. We write to bring to your attention to a serious conflict of interest regarding Marc Elias, an attorney with the law firm Perkins Coie. In the election contests currently before us, Mr. Elias simultaneously represents Members of the Committee, the triers of fact and law, and parties to these contests, an arrangement clearly prohibited by attorney ethics rules and obligations. See Notice of Contest Regarding Election for Representative in the One Hundred Seventeenth Congress from Iowa’s Second Congressional District; Contestee’s Motion to dismiss Contestant’s Notice of Contest Regarding the Election for Representative in the 117th Congress from Illinois’ fourteenth Congressional District. Marc Elias and his firm, Perkins Coie, represent you, Representative Pete Aguilar, and Representative Mary Gay Scanlon, one-half of the Democratic Members of the House Committee on House Administration, the Committee charged with hearing election contests. -

Community Development Bank City State ABC Bank CHICAGO IL Albina Community Bank PORTLAND OR American Metro Bank CHICAGO IL Aztec

Community Development Bank City State ABC Bank CHICAGO IL Albina Community Bank PORTLAND OR American Metro Bank CHICAGO IL AztecAmerica Bank BERWYN IL Bank 2 OKLAHOMA CITY OK Bank of Cherokee County, Inc. TAHLEQUAH OK Bank of Kilmichael KILMICHAEL MS Bank of Okolona OKOLONA MS BankFirst Financial Services MACON MS BankPlus RIDGELAND MS Broadway Federal Bank LOS ANGELES CA Capitol City Bank & Trust Company ATLANTA GA Carver Federal Savings Bank NEW YORK NY Carver State Bank SAVANNAH GA Central Bank of Kansas City KANSAS CITY MO Citizens Bank of Weir WEIR KS Citizens Savings Bank and Trust Company NASHVILLE TN Citizens Trust Bank ATLANTA GA City First Bank of D.C., N.A. WASHINGTON DC City National Bank of New Jersey NEWARK NJ Commercial Capital Bank DEHLI LA Commonwealth National Bank MOBILE AL Community Bank of the Bay OAKLAND CA Community Capital Bank of Virginia CHRISTIANSBURG VA Community Commerce Bank CLAREMONT CA Edgebrook Bank CHICAGO IL First American International Bank BROOKLYN NY First Choice Bank CERRITOS CA First Eagle Bank CHICAGO IL First Independence Bank DETROIT MI First National Bank of Decatur County BAINBRIDGE GA First Security Bank BATESVILLE MS First Tuskegee Bank MONTGOMERY AL Fort Gibson State Bank FORT GIBSON OK Gateway Bank Federal Savings Bank OAKLAND CA Guaranty Bank & Trust BELZONI MS Harbor Bank of Maryland BALTIMORE MD Illinois Service Federal Savings and Loan Association CHICAGO IL Industrial Bank WASHINGTON DC International Bank of Chicago STONE PARK IL Liberty Bank and Trust Company NEW ORLEANS LA Magnolia State Bank BAY SPRINGS MS Mechanics and Farmers Bank DURHAM NC Merchants & Planters Bank RAYMOND MS Metro Bank LOUISVILLE KY Current as of 12-15-2013 Source: CDFI Fund Community Development Bank City State Mission Valley Bank SUN VALLEY CA Mitchell Bank MILWAUKEE WI Native American Bank, N.A. -

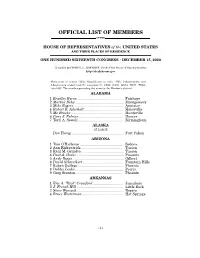

Official List of Members

OFFICIAL LIST OF MEMBERS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES of the UNITED STATES AND THEIR PLACES OF RESIDENCE ONE HUNDRED SIXTEENTH CONGRESS • DECEMBER 15, 2020 Compiled by CHERYL L. JOHNSON, Clerk of the House of Representatives http://clerk.house.gov Democrats in roman (233); Republicans in italic (195); Independents and Libertarians underlined (2); vacancies (5) CA08, CA50, GA14, NC11, TX04; total 435. The number preceding the name is the Member's district. ALABAMA 1 Bradley Byrne .............................................. Fairhope 2 Martha Roby ................................................ Montgomery 3 Mike Rogers ................................................. Anniston 4 Robert B. Aderholt ....................................... Haleyville 5 Mo Brooks .................................................... Huntsville 6 Gary J. Palmer ............................................ Hoover 7 Terri A. Sewell ............................................. Birmingham ALASKA AT LARGE Don Young .................................................... Fort Yukon ARIZONA 1 Tom O'Halleran ........................................... Sedona 2 Ann Kirkpatrick .......................................... Tucson 3 Raúl M. Grijalva .......................................... Tucson 4 Paul A. Gosar ............................................... Prescott 5 Andy Biggs ................................................... Gilbert 6 David Schweikert ........................................ Fountain Hills 7 Ruben Gallego ............................................