Patellofemoral Pain 1 Running Head: REVIEW of LITERATURE What Effect Does Grafting from the Contralateral Patellar Tendon in P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Influence of Altered Lower-Extremity Kinematics on Patellofemoral Joint Dysfunction: a Theoretical Perspective

The Influence of Altered Lower-Extremity Kinematics on Patellofemoral Joint Dysfunction: A Theoretical Perspective Christopher M. Powers, PT, PhD 1 Although patellofemoral pain (PFP) is recognized as being one of the most common disorders of It has been recognized by sev- the lower extremity, treatment guidelines and underlying rationales remain vague and controver- eral authors that the patel- sial. The premise behind most treatment approaches is that PFP is the result of abnormal patellar lofemoral joint may be influenced CLINICAL COMMENTARY tracking and/or patellar malalignment. Given as such, interventions typically focus on the joint by the segmental interactions of itself and have traditionally included strengthening the vastus medialis oblique, taping, bracing, the lower extremity.6,7,21,27,34,45 Ab- soft tissue mobilization, and patellar mobilization. More recently, it has been recognized that the normal motion(s) of the tibia and patellofemoral joint and, therefore, PFP may be influenced by the interaction of the segments and femur in the transverse and frontal joints of the lower extremity. In particular, abnormal motion of the tibia and femur in the transverse and frontal planes may have an effect on patellofemoral joint mechanics. With this in planes are believed to have an mind, interventions aimed at controlling hip and pelvic motion (proximal stability) and ankle/foot effect on patellofemoral joint me- motion (distal stability) may be warranted and should be considered when treating persons with chanics and therefore PFP. An un- patellofemoral joint dysfunction. The purpose of this paper is to provide a biomechanical derstanding of how lower- overview of how altered lower-extremity mechanics may influence the patellofemoral joint. -

Closure of Patellar Tendon Defect in ACL Reconstruction

Systematic Review Closure of Patellar Tendon Defect in Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction With BoneePatellar TendoneBone Autograft: Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials Rachel M. Frank, M.D., Randy Mascarenhas, M.D., Marc Haro, M.D., Nikhil N. Verma, M.D., Brian J. Cole, M.D., M.B.A., Charles A. Bush-Joseph, M.D., and Bernard R. Bach Jr., M.D. Purpose: This study aimed to systematically review the highest level of evidence on anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction with boneepatellar tendonebone (BPTB) autografts with patellar tendon defect closure versus no closure after surgery. Methods: We performed a systematic review of multiple medical databases using Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. Level I and Level II randomized controlled trials comparing patellar tendon defect closure to no closure during ACL reconstruction with BPTB autografts were included. Two inde- pendent reviewers analyzed all studies. Descriptive statistics were calculated. Study methodological quality was analyzed using the Modified Coleman Methodology Score (MCMS) and Jadad scale. Results: Four studies with a combined 221 patients (154 male patients and 67 female patients) with an average age of 26.6 Æ 2.4 years (range, 17 to 54 years) were included. All studies randomized patients before surgery into ACLR with BPTB autografts either with patellar tendon defect closure or without closure. There were no differences in clinical outcomes (Lysholm score, Tegner scale, International Knee Documentation Committee [IKDC] classification, modified Larsen score, and Lauridsen rating) between groups. There were no significant differences in knee pain between groups. All studies reported imaging findings of the patellar tendon defect, with 2 studies showing no difference in appearance between groups, one study showing excessive scar formation with defect repair, and one study showing improved restoration of normal tendon appearance with defect repair. -

Physical Examination of the Knee: Meniscus, Cartilage, and Patellofemoral Conditions

Review Article Physical Examination of the Knee: Meniscus, Cartilage, and Patellofemoral Conditions Abstract Robert D. Bronstein, MD The knee is one of the most commonly injured joints in the body. Its Joseph C. Schaffer, MD superficial anatomy enables diagnosis of the injury through a thorough history and physical examination. Examination techniques for the knee described decades ago are still useful, as are more recently developed tests. Proper use of these techniques requires understanding of the anatomy and biomechanical principles of the knee as well as the pathophysiology of the injuries, including tears to the menisci and extensor mechanism, patellofemoral conditions, and osteochondritis dissecans. Nevertheless, the clinical validity and accuracy of the diagnostic tests vary. Advanced imaging studies may be useful adjuncts. ecause of its location and func- We have previously described the Btion, the knee is one of the most ligamentous examination.1 frequently injured joints in the body. Diagnosis of an injury General Examination requires a thorough knowledge of the anatomy and biomechanics of When a patient reports a knee injury, the joint. Many of the tests cur- the clinician should first obtain a rently used to help diagnose the good history. The location of the pain injured structures of the knee and any mechanical symptoms were developed before the avail- should be elicited, along with the ability of advanced imaging. How- mechanism of injury. From these From the Division of Sports Medicine, ever, several of these examinations descriptions, the structures that may Department of Orthopaedics, are as accurate or, in some cases, University of Rochester School of have been stressed or compressed can Medicine and Dentistry, Rochester, more accurate than state-of-the-art be determined and a differential NY. -

Patellar Tendinopathy: Some Aspects of Basic Science and Clinical Management

346 Br J Sports Med 1998;32:346–355 Br J Sports Med: first published as 10.1136/bjsm.32.4.346 on 1 December 1998. Downloaded from OCCASIONAL PIECE Patellar tendinopathy: some aspects of basic science and clinical management School of Human Kinetics, University of K M Khan, N MaVulli, B D Coleman, J L Cook, J E Taunton British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada K M Khan J E Taunton Tendon injuries account for a substantial tendinopathy, and the remainder to tendon or Victorian Institute of proportion of overuse injuries in sports.1–6 tendon structure in general. Sport Tendon Study Despite the morbidity associated with patellar Group, Melbourne, tendinopathy in athletes, management is far Victoria, Australia 7 Anatomy K M Khan from scientifically based. After highlighting The patellar tendon, the extension of the com- J L Cook some aspects of clinically relevant basic sci- mon tendon of insertion of the quadriceps ence, we aim to (a) review studies of patellar femoris muscle, extends from the inferior pole Department of tendon pathology that explain why the condi- of the patella to the tibial tuberosity. It is about Orthopaedic Surgery, tion can become chronic, (b) summarise the University of Aberdeen 3 cm wide in the coronal plane and 4 to 5 mm Medical School, clinical features and describe recent advances deep in the sagittal plane. Macroscopically it Aberdeen, Scotland, in the investigation of this condition, and (c) appears glistening, stringy, and white. United Kingdom outline conservative and surgical treatment NMaVulli options. BLOOD SUPPLY Department of The blood supply has been postulated to con- 89 Medicine, University tribute to patellar tendinopathy. -

Patellar Tendon Debridement Surgery

175 Cambridge Street, 4th floor Boston, MA 02114 Tel: 617-726-7500 PATELLAR TENDON DEBRIDEMENT SURGERY PREOPERATIVE INSTRUCTIONS Here are guidelines that will help you prepare for surgery: WITHIN ONE MONTH BEFORE SURGERY: The doctor will see you in the office. The doctor or his associate will do a preoperative history and physical examination and complete the necessary paperwork. He will write preoperative hospital orders and order laboratory tests. These tests usually include a complete blood count (and also electrocardiogram for patients over 40 years old.) SEVERAL DAYS BEFORE SURGERY: Wash the knee several times a day to get it as clean as you can. This decreases the risk of infection. Be careful not to get any scratches, cuts, sunburn, poison ivy, etc. The skin has to be in very good shape to prevent problems. You do not need to shave the knee. THE DAY BEFORE SURGERY: Please contact the doctor’s office to get the exact time you should report to the hospital for surgery. You can have nothing to eat or drink after midnight on the evening before surgery. It is very important to have a completely empty stomach prior to surgery for anesthesia safety reasons. If you have to take medication, you can take the medication with a sip of water early in the morning prior to surgery (but later tell the anesthesiologist you have done so). THE DAY OF SURGERY: Surgery is performed in the Wang building at MGH and at the Orthopedic Ambulatory Surgery Center at Mass General West in Waltham. • nothing to eat or drink • For surgery at MGH main campus in Boston: Report directly to the 12th floor of the Lunder Building, Center for Preoperative Care at Massachusetts General Hospital, two hours prior to surgery. -

Recurrent Unremitting Patellar Tendonitis/ Tendonosis Rehabilitation Program

Page 1 of 3 Recurrent Unremitting Patellar Tendonitis/ Tendonosis Rehabilitation Program I. Phase I Goals: Diminish pain and inflammation Promote tendon healing Improve quadriceps strength Enhance flexibility Control functional stresses Treatment Regimen: • Hot packs applied to knee • Ultrasound to patellar tendon • Transverse friction massage • Warm-up bicycle (10-12 min.) • Stretch (hamstrings quadriceps, gastroc) • Application of pain stimulation to each side of patella tendon or infra-patellar fat pad x 10 minutes • Electrical stimulation parameters • Waveform: Russian • Frequency: 2500 H2 pulse; width: 200 MS; Rate: 50/sec • 60 pulses per second (pps) • duty cycle 10 on/10 off; ramp of 1 second • pad placement- 1”x1” electrodes placed on each side of inflamed/painful tendon (After 3 minutes, palpate tendon, should be less painful and becoming numb, if not, move electrodes) • Quadriceps strengthening program (Level I) • E-stim to quadriceps* • Quad sets* • SLR flexion* • Hip adduction/abduction* • Vertical squats (tilt board) • Hip flexion/extension • Toe-calf raises • Bicycle (15-20 min.) *Monitor subjective pain level response (goal level 5-7) • Pool program • Stretch (aggressive stretching) • Laser • Cryotherapy II. Phase II Emphasize eccentric training for quadriceps Goals: Gradual increase stress to patellar tendon Enhance quadriceps strength Improve flexibility Gradual increase functional activities Copyright © by the Advanced Continuing Education Institute, LLC. AdvancedCEU.com. All Rights Reserved. Any redistribution, alteration, -

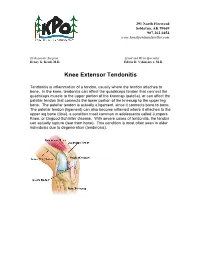

Knee Extensor Tendonitis

291 North Fireweed Soldotna, AK 99669 907-262-6454 www.kenaipeninsulaortho.com ______________________________________________________________________________________ Orthopaedic Surgeon: Hand and Wrist Specialist: Henry G. Krull, M.D. Edwin D. Vyhmeister, M.D. Knee Extensor Tendonitis Tendonitis is inflammation of a tendon, usually where the tendon attaches to bone. In the knee, tendonitis can affect the quadriceps tendon that connect the quadriceps muscle to the upper portion of the kneecap (patella), or can affect the patellar tendon that connects the lower portion of the kneecap to the upper leg bone. The patellar tendon is actually a ligament, since it connects bone to bone. The patellar tendon (ligament) can also become inflamed where it attaches to the upper leg bone (tibia), a condition most common in adolescents called Jumpers Knee, or Osgood-Schlatter disease. With severe cases of tendonitis, the tendon can actually rupture (tear from bone). This condition is most often seen in older individuals due to degeneration (tendinosis). 291 North Fireweed Soldotna, AK 99669 907-262-6454 www.kenaipeninsulaortho.com Symptoms: Pain is the hallmark of extensor tendonitis, and is located either just above the patella (quadriceps tendonitis), or just below the patella (patellar tendonitis). Sometimes there is an injury, but tendonitis is more common with overuse and under-conditioning. There is occasionally swelling and warmth over the inflamed tendon. The joint may become stiff, but range of motion is often reduced due to pain. Tenderness is present over the affected tendon. Cause: Extensor tendonitis is often caused by injury, particularly sports injuries, or overuse. Tendonitis can often be caused by inadequate stretching prior to exercise, or increasing an exercise program too rapidly. -

Patellar Tendon Tear

DISEASES & CONDITIONS Patellar Tendon Tear Tendons are strong cords of fibrous tissue that attach muscles to bones. The patellar tendon works with the muscles in the front of your thigh to straighten your leg. Small tears of the tendon can make it difficult to walk and participate in other daily activities. A large tear of the patellar tendon is a disabling injury. It usually requires surgery and physical therapy to regain full knee function. Anatomy The tendons of the knee. Muscles are connected to bones by tendons. The patellar tendon attaches the bottom of the kneecap (patella) to the top of the shinbone (tibia). It is actually a ligament that connects to two different bones, the patella and the tibia. The patella is attached to the quadriceps muscles by the quadriceps tendon. Working together, the quadriceps muscles, quadriceps tendon and patellar tendon straighten the knee. Description Patellar tendon tears can be either partial or complete. Partial tears. Many tears do not completely disrupt the soft tissue. This is similar to a rope stretched so far that some of the fibers are frayed, but the rope is still in one piece. Complete tears. A complete tear will disrupt the soft tissue into two pieces. When the patellar tendon is completely torn, the tendon is separated from the kneecap. Without this attachment, you cannot straighten your knee. The patellar tendon often tears at the place where it attaches to the kneecap, and a piece of bone can break off along with the tendon. When a tear is caused by a medical condition — like tendinitis — the tear usually occurs in the middle of the tendon. -

The Effectiveness of Using Foot Orthotics As the Sole Intervention for the Treatment of Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome" (2000)

Grand Valley State University ScholarWorks@GVSU Masters Theses Graduate Research and Creative Practice 2000 The ffecE tiveness of Using Foot Orthotics as the Sole Intervention for the Treatment of Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome Byron Horner Grand Valley State University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/theses Part of the Physical Therapy Commons Recommended Citation Horner, Byron, "The Effectiveness of Using Foot Orthotics as the Sole Intervention for the Treatment of Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome" (2000). Masters Theses. 626. http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/theses/626 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research and Creative Practice at ScholarWorks@GVSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@GVSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE EFFECTIVENESS OF USING FOOT ORTHOTICS AS THE SOLE INTERVENTION FOR THE TREATMENT OF PATELLOFEMORAL PAIN SYNDROME By Byron Homer MASTERS' THESIS Submitted to the Department of Physical Therapy at Grand Valley State University Allendale, Michigan in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN PHYSICAL THERAPY 2000 THESIS COMMITTEE/RESEARCH ADVISOR A^ROVAL: /VicinberJk , Member Dele A L®co ^^^^ember Dale THE EFFECTIVENESS OF USING FOOT ORTHOTICS AS THE SOLE INTERVENTION FOR THE TREATMENT OF PATELLOFEMORAL PAIN SYNDROME ABSTRACT Patellofemoral pain syndrome (PFPS) is a common diagnosis treated by health care personnel. This study investigates the effectiveness of foot orthotics in the treatment of PFPS. Fourteen subjects experiencing PFPS participated. Each completed a Functional Pain Assessment (FPA) consisting of walking, stairs, biking, squatting and resting (sitting). -

Rehabilitation Guidelines for Patellar Tendon and Quadriceps Tendon Repair

UW HEALTH SPORTS REHABILITATION Rehabilitation Guidelines for Patellar Tendon and Quadriceps Tendon Repair The knee consists of four bones that form three joints. The femur is the large bone in the thigh and attaches by ligaments and a capsule to the tibia, the large bone below the knee Quadriceps commonly referred to as the shin Tendon bone. Next to the tibia is the fibula, Patella which runs parallel to the tibia on the outside of the leg. The patella, commonly called the knee cap, is Patellar Tendon embedded in the quadriceps and patellar tendon which articulates with the front of the femur, forming the patellofemoral joint (Figure 1). The patella acts as a pulley to increase the amount of force that the quadriceps muscle can generate and helps direct the force in the desired Figure 1. Front view of normal knee anatomy, Figure 2. Front view of knee after patellar tendon repair. The primary sutures repair the upward direction. showing the quadriceps tendon above the patella (knee cap) and patellar tendon below torn tendon and the relaxing suture Complete ruptures or partial tears the patella. encompasses the repair and goes around the of the patellar tendon or quadriceps patella, providing initial protection to the repaired portion of the tendon. tendon can result from landing from weaken the quadriceps tendon or patellar tendon and make it more a jump, a fall causing excessive knee holes in the knee cap for fixation. susceptible to rupture. The nature flexion or other heavy loading of the In some cases graft tissue may and size of the tear, the age of the tendon. -

Patella Tibia Patella Tendon Tibial Tubercle Screw

601 West Fifth Avenue, Suite 400 Spokane, WA 99204 Tibial Tubercle Osteotomy Overview This procedure, also called bone realignment, is designed to improve the movement of the patella (the kneecap) to correct patellar tracking disorder. The procedure usually requires hospitalization and general anesthesia. Incision Made After anesthesia is administered, the surgeon makes a four- to six-inch incision over the tibial tubercle. Patella Tubercle Detached The surgeon uses a bone chisel and/or a surgical saw to partially or completely detach the tibial Patella tubercle from the tibia. The patellar tendon, which tendon connects the patella to the tibia, remains connected to the tubercle. Tibia Tubercle Realigned Tibial The tibial tubercle is realigned with the patella in a tubercle position that allows for proper movement when the knee bends. Once in place, the bone is reattached to the tibia with a metal plate, wires or screws. The attachment parts are permanent unless they cause pain. If they do, they can be removed after the bone has healed in its new position. Patella Adjusted In some cases, attachments on either side of the patella may be loosened or tightened to ensure Medial retinaculum proper alignment of the patella. This procedure is may be tightened called lateral release and medial imbrication. (imbrication). End of Procedure The incision is closed with sutures or staples, and a cast or knee immobilizer is placed around the knee to restrict movement. The knee is iced and elevated. The sutures or staples are removed after two to three weeks. The knee will be swollen and Tibial crutches may be necessary for four to six weeks, tubercle with physical therapy to follow. -

Patellar Tendinopathy and Patellar Tendon Rupture

18 Patellar Tendinopathy and Patellar Tendon Rupture Karim M. Khan, Jill L. Cook, and Nicola Maffulli Introduction detecting patellar tendinopathy, but mild tenderness at this site is not unusual in a normal tendon. Only moder- Patellar tendon injuries constitute a significant problem ate and severe tenderness is significantly associated with in a wide variety of sports [1–4]. Despite the morbidity tendon abnormality as defined by ultrasonography. Thus, associated with patellar tendinopathy, clinical manage- we suggest that mild patellar tendon tenderness should ment remains largely anecdotal [5] as there have few not be overinterpreted, and may be a normal finding in well-designed treatment studies. This chapter will update active athletes. the reader on management of 1) the patient with overuse Patients with chronic symptoms may exhibit quadri- patellar tendinopathy, and 2) the patient unfortunate ceps wasting, most notably in the vastus medialis enough to suffer the less common, but debilitating, con- obliquus. Thigh circumference may be diminished, and dition of patellar tendon rupture. calf muscle atrophy may be present. Testing the func- tional strength of the quadriceps may be done by com- Typical Clinical Scenario—Patellar paring the ease with which the patient can perform 15 Tendinopathy one-legged stepdowns on each leg. The athlete bends at the knee and then straightens again without letting the In the patient with patellar tendinopathy, knee pain may other foot touch the floor. Work capacity of the calf is arise insidiously.Those patients who recall when the pain assessed by asking the patient to do single-leg heel raises. began report that it started during one heavy training Jumping athletes should be able to do at least 40 raises.