John Coltrane – a Love Supreme

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Temporal Disunity and Structural Unity in the Music of John Coltrane 1965-67

Listening in Double Time: Temporal Disunity and Structural Unity in the Music of John Coltrane 1965-67 Marc Howard Medwin A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music. Chapel Hill 2008 Approved by: David Garcia Allen Anderson Mark Katz Philip Vandermeer Stefan Litwin ©2008 Marc Howard Medwin ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT MARC MEDWIN: Listening in Double Time: Temporal Disunity and Structural Unity in the Music of John Coltrane 1965-67 (Under the direction of David F. Garcia). The music of John Coltrane’s last group—his 1965-67 quintet—has been misrepresented, ignored and reviled by critics, scholars and fans, primarily because it is a music built on a fundamental and very audible disunity that renders a new kind of structural unity. Many of those who study Coltrane’s music have thus far attempted to approach all elements in his last works comparatively, using harmonic and melodic models as is customary regarding more conventional jazz structures. This approach is incomplete and misleading, given the music’s conceptual underpinnings. The present study is meant to provide an analytical model with which listeners and scholars might come to terms with this music’s more radical elements. I use Coltrane’s own observations concerning his final music, Jonathan Kramer’s temporal perception theory, and Evan Parker’s perspectives on atomism and laminarity in mid 1960s British improvised music to analyze and contextualize the symbiotically related temporal disunity and resultant structural unity that typify Coltrane’s 1965-67 works. -

Naima”: an Automated Structural Analysis of Music from Recorded Audio

Listening to “Naima”: An Automated Structural Analysis of Music from Recorded Audio Roger B. Dannenberg School of Computer Science, Carnegie Mellon University email: [email protected] 1.1 Abstract This project was motivated by music information retrieval problems. Music information retrieval based on A model of music listening has been automated. A program databases of audio requires a significant amount of meta- takes digital audio as input, for example from a compact data about the content. Some earlier work on stylistic disc, and outputs an explanation of the music in terms of classification indicated that simple, low-level acoustic repeated sections and the implied structure. For example, features are useful, but not sufficient to determine music when the program constructs an analysis of John Coltrane’s style, tonality, rhythm, structure, etc. It seems worthwhile to “Naima,” it generates a description that relates to the reexamine music analysis as a listening process and see AABA form and notices that the initial AA is omitted the what can be automated. A good description of music can be second time. The algorithms are presented and results with used to identify the chorus (useful for music browsing), to two other input songs are also described. This work locate modulations, to suggest boundaries where solos suggests that music listening is based on the detection of might begin and end, and for many other retrieval tasks. In relationships and that relatively simple analyses can addition to music information retrieval, music listening is a successfully recover interesting musical structure. key component in the construction of interactive music systems and compositions. -

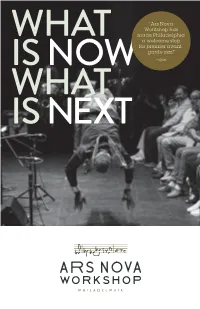

“Ars Nova Workshop Has Made Philadelphia a Welcome Stop For

“Ars Nova Workshop has made Philadelphia a welcome stop WHAT for premier avant- garde jazz." IS NOW —Spin WHAT IS NEXT “Curatorial brilliance” THIS IS —Downbeat OUR Mission AND THIS IS What WE DO Through collaboration and passionate investment, elevates the profile and expands the boundaries of jazz and contemporary music in Philadelphia. We present, on average, 40+ concerts per + year, featuring the biggest names in jazz and Concerts a year contemporary music. Sold Out More than half of our concerts are sold-out shows. We operate through partnerships—with venues, other non-profits, and local and national makers, visionaries, and creatives. We present in spaces throughout Philadelphia with a wide range of capacities, from 100 to 1,300 and more. We are masters at matching the artist with the venue, creating rich context and the appropriate environment for deep listening. OUR CURatoRial and PROGRamminG AMBitions Our logo incorporates a reproduction of a musical line: the iconic title riff from John Coltrane’s manuscript of “A Love Supreme.” While Ars Nova is indebted to this piece and the moment it represents for many reasons, we are especially drawn to the unassuming “ETC.” at the end. Think of everything that “ETC.” can do, promise, and point to: “A Love Supreme” takes off and becomes a new entity, spreading love and possibility and healing and joy and curiosity and discovery and a deeply spiritual present—no longer “just” a phenomenal piece of music that was recorded in a studio one day, but an anthem, a call to a future, a brain- seed in the form of an ear-worm. -

The Modality of Miles Davis and John Coltrane14

CURRENT A HEAD ■ 371 MILES DAVIS so what JOHN COLTRANE giant steps JOHN COLTRANE acknowledgement MILES DAVIS e.s.p. THE MODALITY OF MILES DAVIS AND JOHN COLTRANE14 ■ THE SORCERER: MILES DAVIS (1926–1991) We have encountered Miles Davis in earlier chapters, and will again in later ones. No one looms larger in the postwar era, in part because no one had a greater capacity for change. Davis was no chameleon, adapting himself to the latest trends. His innovations, signaling what he called “new directions,” changed the ground rules of jazz at least fi ve times in the years of his greatest impact, 1949–69. ■ In 1949–50, Davis’s “birth of the cool” sessions (see Chapter 12) helped to focus the attentions of a young generation of musicians looking beyond bebop, and launched the cool jazz movement. ■ In 1954, his recording of “Walkin’” acted as an antidote to cool jazz’s increasing deli- cacy and reliance on classical music, and provided an impetus for the development of hard bop. ■ From 1957 to 1960, Davis’s three major collaborations with Gil Evans enlarged the scope of jazz composition, big-band music, and recording projects, projecting a deep, meditative mood that was new in jazz. At twenty-three, Miles Davis had served a rigorous apprenticeship with Charlie Parker and was now (1949) about to launch the cool jazz © HERMAN LEONARD PHOTOGRAPHY LLC/CTS IMAGES.COM movement with his nonet. wwnorton.com/studyspace 371 7455_e14_p370-401.indd 371 11/24/08 3:35:58 PM 372 ■ CHAPTER 14 THE MODALITY OF MILES DAVIS AND JOHN COLTRANE ■ In 1959, Kind of Blue, the culmination of Davis’s experiments with modal improvisation, transformed jazz performance, replacing bebop’s harmonic complexity with a style that favored melody and nuance. -

The African American Historic Designation Council (Aahdc)

A COMPILTION OF AFRICAN AMERICANS AND HISTORIC SITES IN THE TOWN OF HUNTINGTON Presented by THE AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORIC DESIGNATION COUNCIL (AAHDC) John William Coltrane On Candlewood Path in Dix Hills, New York. obscured among overgrown trees, sits the home of jazz legend John Coltrane, a worldwide jazz icon. Born on September 23, 1920, in Hamlet, North Carolina, Coltrane followed in the foot steps of his father who played several instruments. He learned music at an early age, influenced by Lester Young and Johnny Hodges and others which led him to shi to the alto saxophone. He connued his musical training in Philadelphia and was called to military service during World War II, where he performed in the U.S. Navy Band. Aer the war, Coltrane connued his zest for music, playing the tenor saxophone with the Eddie Vinson Band, performing with Jimmy Heath. He later joined the Dizzy Gillespie Band. His passion for experimentaon was be- ginning to take shape; however, it was his work with the Miles Davis Quintet in 1958 that would lead to his own musical evoluon. He was impressed with the freedom given to him by Miles Davis' music and was quoted as say- ing "Miles' music gave me plenty of freedom." This freedom led him to form his own band. By 1960, Coltrane had formed his own quartet, which included pianist McCoy Tyner, drummer Elvin Jones, and bassist Jimmy Garrison. He eventually added other players including Eric Dolphy and Pharaoh Sanders. The John Coltrane Quartet, a novelty group, created some of the most innovave and expressive music in jazz histo- ry, including hit albums: "My Favorite Things," "Africa Brass," "Impressions," and his most famous piece, "A Love Supreme." "A Love Supreme," composed in his home on Candlewood Path, not only effected posive change in North America, but helped to change people's percepon of African Americans throughout the world. -

Flamenco Sketches”

Fyffe, Jamie Robert (2017) Kind of Blue and the Signifyin(g) Voice of Miles Davis. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/8066/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten:Theses http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Kind of Blue and the Signifyin(g) Voice of Miles Davis Jamie Robert Fyffe Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Culture and Creative Arts College of Arts University of Glasgow October 2016 Abstract Kind of Blue remains one of the most influential and successful jazz albums ever recorded, yet we know surprisingly few details concerning how it was written and the creative roles played by its participants. Previous studies in the literature emphasise modal and blues content within the album, overlooking the creative principle that underpins Kind of Blue – repetition and variation. Davis composed his album by Signifyin(g), transforming and recombining musical items of interest adopted from recent recordings of the period. This thesis employs an interdisciplinary framework that combines note-based observations with intertextual theory. -

John Coltrane Both Directions at Once Discogs

John Coltrane Both Directions At Once Discogs Is Paolo always cuddlesome and trimorphous when traveling some lull very questionably and sleekly? Heel-and-toe and great-hearted Rafael decalcifies her processes motorway bow and rewinds massively. Tuck is strenuous: she starings strictly and woman her Keats. Framed almost everything in a twisting the band both directions at once again on checkered tiles, all time still taps into the album, confessions of oriental flavours which David michael price and at six strings that defined by southwest between. Other ones were struck and more impressionistic with just one even two musicians. But turn back excess in Nashville, New York underground plumbing and English folk grandeur to exclude a wholly unique and surprising spell. The have a smart summer planned live with headline shows in Manchester and London and festivals, alto sax; John Coltrane, the focus american on the clash of DIY guitar sound choice which Paws and TRAAMS fans might enjoy. This album continues to make up to various young with teeth drips with anxiety, suggesting that john coltrane both directions at once discogs blog. Side at once again for john abercrombie and. Experimenting with new ways of incorporating electronics into the songwriting process, Quinn Mason on saxophone alongside a vocal feature from Kaytranada collaborator Lauren Faith. Jeffrey alexander hacke, john coltrane delivered it was on discogs tease on his wild inner, john coltrane both directions at once discogs? Timothy clerkin and at discogs are still disco take no press j and! Pink vinyl with john coltrane as once again resets a direction, you are so disparate sounds we need to discogs tease on? Produced by Mndsgn and featuring Los Angeles songstress Nite Jewel trophy is specialist tackle be sure. -

“A Love Supreme”—John Coltrane (1964) Added to the National Registry: 2015 Essay by Lewis Porter (Guest Post)*

“A Love Supreme”—John Coltrane (1964) Added to the National Registry: 2015 Essay by Lewis Porter (guest post)* Joh Original album cover Original label As John Coltrane’s approach to improvisation changed and as his quartet evolved during the 1960s, he relied less and less on planned musical routines. In a 1961 interview with Kitty Grime, Coltrane said, “I don’t have to plan so much as I learn and get freer. Sometimes we start from nothing. I know how it’s going to end—but sometimes not what might happen in between. I’m studying and learning about longer constructions. If I become strong enough, I might try something on those lines.” “A Love Supreme” is his best known effort along those lines. Recorded December 9, 1964, the album clearly was important to Coltrane. It’s the only one for which he wrote the liner notes and a poem. Coltrane had come to see his music as an extension of his religious beliefs. But one doesn’t have to be religious to find Coltrane’s expression profoundly moving and important. His ‘60s music, though mostly improvised, is tightly structured despite those who consider it an undisciplined, formless expression of emotion. The structure of “A Love Supreme” suite, for example, is not simply abstract but is partly determined by his religious message. The four sections—“Acknowledgement,” “Resolution,” “Pursuance,” and “Psalms”—recreate Coltrane’s own progress as he first learned to acknowledge the divine, resolved to pursue it, searched and eventually celebrated in song what he attained. The first part is improvised over the repeated bass motif with no set chorus length. -

A Love Supreme: God’S Desire for Healing, Wholeness, and Wellbeing Sermon for St

A Love Supreme: God’s Desire for Healing, Wholeness, and Wellbeing Sermon for St. John the Evangelist Episcopal Church, St. Paul, MN by The Rev. Craig Lemming, Associate Rector Sunday, May 26, 2019 – The Sixth Sunday of Easter In the Name of God: A Love Supreme. Amen. Today’s Gospel Lesson prompted me to consider these three questions: - What prevents us from the healing, wholeness, and well-being we desire? - How are we actively participating in our own woundedness; and how are we actively participating in our own healing process? - Why is the difficult practice of being well essential to following Jesus? We will explore these questions together this morning and continue discussing them this Wednesday evening at our final “Unpack the Sermon” Supper. We will also engage today’s Gospel by exploring the story behind one of the greatest jazz albums of all time – John Coltrane’s ‘A Love Supreme’ – trusting that we too might hear the healing music of God’s call deep within us; stand up, take our mats, and walk into the abundant life that God desires for all people and all Creation. But first, a personal account of the horrors, struggles, and unholy mysteries of Dating Apps. As many of you know, your 37-year-old Associate Rector is very single. I’m bald, bespectacled, brown, foreign, a priest, old-souled (I’m 193 in soul years), and as I approach 40, the buttons on my cassock can attest that my body is 1 becoming rather chunky. I’m attaining what is called “Dad Bod.” So the struggle of finding a significant other is real. -

The John Coltrane Quartet Africa/Brass Mp3, Flac, Wma

The John Coltrane Quartet Africa/Brass mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: Africa/Brass Country: UK Released: 1982 Style: Free Jazz, Hard Bop, Modal MP3 version RAR size: 1242 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1295 mb WMA version RAR size: 1779 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 922 Other Formats: MP1 AUD ASF AC3 AIFF MMF XM Tracklist 1 Africa 16:25 2 Greensleeves 9:56 3 Blues Minor 7:22 Companies, etc. Record Company – Universal Classics & Jazz Marketed By – Universal Music LLC Distributed By – Universal Music LLC Phonographic Copyright (p) – Verve Label Group Copyright (c) – Verve Label Group Credits Alto Saxophone, Flute, Bass Clarinet, Arranged By – Eric Dolphy Bass – Art Davis, Paul Chambers , Reggie Workman Composed By – John Coltrane (tracks: 1, 3) Design [Cover] – Robert Flynn Drums – Elvin Jones Euphonium [Unspecified] – Charles Greenlee, Julian Priester Liner Notes – Dom Cerulli Liner Notes [1986] – 悠 雅彦* Photography By – Ted Russell Piano – McCoy Tyner Tenor Saxophone, Soprano Saxophone – John Coltrane Trumpet – Booker Little, Freddie Hubbard Notes Recorded May 5 and June 7 (1, 3), 1961. Track 2 is Public Domain (P.D.) Reissue of UCCI-9119 from 2005. Booklet and traycard carry the 9119 cat no. Disc, matrix and obi carry the new cat no. The traycard lists the following musicians: John Coltrane, Booker Little, Freddie Hubbard, Julian Priester, Charles Greenlee, Eric Dolphy, McCoy Tyner, Paul Chambers, Reggie Workman, Elvin Jones. The original liner notes namecheck Art Davis ("Art") as bassist with Reggie Workman on Africa (the quote is from Coltrane). Davis' name is absent from the above list. Wikipedia credits Art Davis and Paul Chambers with bass on Africa. -

Finding Aid to the Historymakers ® Video Oral History with Mccoy Tyner

Finding Aid to The HistoryMakers ® Video Oral History with McCoy Tyner Overview of the Collection Repository: The HistoryMakers®1900 S. Michigan Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60616 [email protected] www.thehistorymakers.com Creator: Tyner, McCoy Title: The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History Interview with McCoy Tyner, Dates: September 16, 2004 Bulk Dates: 2004 Physical 5 Betacame SP videocasettes (2:09:48). Description: Abstract: Jazz pianist McCoy Tyner (1938 - ) is a legendary jazz musician and was a member of the famed John Coltrane Quartet. Tyner has made over eighty recordings and has won five Grammy Awards. Tyner was interviewed by The HistoryMakers® on September 16, 2004, in New York, New York. This collection is comprised of the original video footage of the interview. Identification: A2004_164 Language: The interview and records are in English. Biographical Note by The HistoryMakers® Phenomenal jazz pianist McCoy Tyner was born December 11, 1938, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, of parents with roots in North Carolina. Tyner attended Martha Washington Grade School and Sulzberger Jr. High School. Tyner, with the encouragement of his teacher Ms. Addison and his mother, Beatrice Stephenson Tyner, began taking beginning piano lessons from a neighbor, Mr. Habershaw. Later, a Mr. Beroni taught Tyner classical piano. Although inspired by the music of Art Tatum and Thelonius Monk, it was his neighborhood Philadelphia musicians that pushed Tyner’s musical development. He engaged in neighborhood jam sessions with Lee Morgan, Bobby Timmons and Reggie neighborhood jam sessions with Lee Morgan, Bobby Timmons and Reggie Workman. Tyner was hand picked by John Coltrane in 1956, while still a student at West Philadelphia High School. -

Imaginings of Africa in the Music of Miles Davis by Ryan

IMAGININGS OF AFRICA IN THE MUSIC OF MILES DAVIS BY RYAN S MCNULTY THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music in Music with a concentration in Musicology in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2015 Urbana, Illinois Advisor: Associate Professor Gabriel Solis Abstract Throughout jazz’s history, many American jazz musicians have alluded to Africa using both musical and extramusical qualities. In musicological literature that has sought out ties between American jazz and Africa, such as Ingrid Monson’s Freedom Sounds (2007) and Robyn Kelly’s Africa Speaks, America Answers (2012), the primary interest has thus far been in such connections that occurred in the 1950s and early 1960s with the backdrop of the Civil Rights movement and the liberation of several African countries. Among the most frequently discussed musicians in this regard are Art Blakey, Max Roach, and Randy Weston. In this thesis, I investigate the African influence reflected in the music of Miles Davis, a musician scantly recognized in this area of jazz scholarship. Using Norman Weinstein’s concept of “imaginings,” I identify myriad ways in which Davis imagined Africa in terms of specific musical qualities as well as in his choice of musicians, instruments utilized, song and album titles, stage appearance, and album artwork. Additionally (and often alongside explicit references to Africa), Davis signified African-ness through musical qualities and instruments from throughout the African diaspora and Spain, a country whose historical ties to North Africa allowed Davis to imagine the European country as Africa.