Read Baroness James of Holland Park's Lecture (Pdf 86KB)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

London National Park City Week 2018

London National Park City Week 2018 Saturday 21 July – Sunday 29 July www.london.gov.uk/national-park-city-week Share your experiences using #NationalParkCity SATURDAY JULY 21 All day events InspiralLondon DayNight Trail Relay, 12 am – 12am Theme: Arts in Parks Meet at Kings Cross Square - Spindle Sculpture by Henry Moore - Start of InspiralLondon Metropolitan Trail, N1C 4DE (at midnight or join us along the route) Come and experience London as a National Park City day and night at this relay walk of InspiralLondon Metropolitan Trail. Join a team of artists and inspirallers as they walk non-stop for 48 hours to cover the first six parts of this 36- section walk. There are designated points where you can pick up the trail, with walks from one mile to eight miles plus. Visit InspiralLondon to find out more. The Crofton Park Railway Garden Sensory-Learning Themed Garden, 10am- 5:30pm Theme: Look & learn Crofton Park Railway Garden, Marnock Road, SE4 1AZ The railway garden opens its doors to showcase its plans for creating a 'sensory-learning' themed garden. Drop in at any time on the day to explore the garden, the landscaping plans, the various stalls or join one of the workshops. Free event, just turn up. Find out more on Crofton Park Railway Garden Brockley Tree Peaks Trail, 10am - 5:30pm Theme: Day walk & talk Crofton Park Railway Garden, Marnock Road, London, SE4 1AZ Collect your map and discount voucher before heading off to explore the wider Brockley area along a five-mile circular walk. The route will take you through the valley of the River Ravensbourne at Ladywell Fields and to the peaks of Blythe Hill Fields, Hilly Fields, One Tree Hill for the best views across London! You’ll find loads of great places to enjoy food and drink along the way and independent shops to explore (with some offering ten per cent for visitors on the day with your voucher). -

London the World’S Changed

LONDON THE WORLD’S CHANGED. Technology now enables us to do so much more, but we can’t forget what it is that inspires us to explore. Whilst celebrating how wonderful technology is, it’s also good to lift your eyes away from the screen and truly get under the skin of a place, seeing it through the eyes of a local. ENCOURAGING CONVERSATIONS, AND DISCOVERING WHERE THEY WILL TAKE YOU. LONDON Our fourth instalment takes you to the world’s most visited city, and the city where it all began for us: London. Experience our own recommendations, whilst starting the conversation and discovering your own favourite hot spots. This is less about exploring the iconic sites and more about getting under the skin of our home city. England LHR ENGLISH GBP +44 Where’s the best place to grab brunch? 1 Head to Chelsea before 11am and go to The Orange for brunch – you’ll want to order the eggs royale and a kiwi, apple & mint juice – it’s one of our favourite brunch spots in London. Ask your server where the best patisserie is nearby to grab some freshly baked treats, then go there. 37-39 Pimlico Road, SW1W 8NE Belgravia Sloane Square (Circle & District Lines) Where’s the best place to go swimming? 2 Pack a picnic, head northwest to Hampstead Heath and take a refreshing dip in the Hampstead swimming ponds; the best place to cool off on a hot summer’s day. Afterwards ask a local where the best stretch of the River Thames to sit with a Pimms is. -

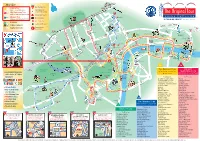

A4 Web Map 26-1-12:Layout 1

King’s Cross Start St Pancras MAP KEY Eurostar Main Starting Point Euston Original Tour 1 St Pancras T1 English commentary/live guides Interchange Point City Sightseeing Tour (colour denotes route) Start T2 W o Language commentaries plus Kids Club REGENT’S PARK Euston Rd b 3 u Underground Station r n P Madame Tussauds l Museum Tour Russell Sq TM T4 Main Line Station Gower St Language commentaries plus Kids Club q l S “A TOUR DE FORCE!” The Times, London To t el ★ River Cruise Piers ss Gt Portland St tenham Ct Rd Ru Baker St T3 Loop Line Gt Portland St B S s e o Liverpool St Location of Attraction Marylebone Rd P re M d u ark C o fo t Telecom n r h Stansted Station Connector t d a T5 Portla a m Museum Tower g P Express u l p of London e to S Aldgate East Original London t n e nd Pl t Capital Connector R London Wall ga T6 t o Holborn s Visitor Centre S w p i o Aldgate Marylebone High St British h Ho t l is und S Museum el Bank of sdi igh s B tch H Gloucester Pl s England te Baker St u ga Marylebone Broadcasting House R St Holborn ld d t ford A R a Ox e re New K n i Royal Courts St Paul’s Cathedral n o G g of Justice b Mansion House Swiss RE Tower s e w l Tottenham (The Gherkin) y a Court Rd M r y a Lud gat i St St e H n M d t ill r e o xfo Fle Fenchurch St Monument r ld O i C e O C an n s Jam h on St Tower Hill t h Blackfriars S a r d es St i e Oxford Circus n Aldwyc Temple l a s Edgware Rd Tower Hil g r n Reg Paddington P d ve s St The Monument me G A ha per T y Covent Garden Start x St ent Up r e d t r Hamleys u C en s fo N km Norfolk -

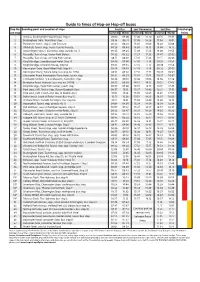

Guide to Times of Hop-On Hop-Off Buses Stop No

Guide to times of Hop-on Hop-off buses Stop No. Boarding point and Location of stops First Bus Last Panoramic Last Bus Interchange (see map) Summer Winter Summer Winter Summer Winter Points 1 Victoria, Buckingham Palace Road, Stop 8. 09:00 09:00 17:00 16:30 20:15 19:45 2 Buckingham Gate, Tourist bus stop. 08:16 08:31 17:08 16:38 17:56 18:01 3 Parliament Street, stop C, HM Treasury. 08:23 08:38 16:03 16:08 18:03 18:08 4 Whitehall, Tourist stop, Horse Guards Parade. 08:28 08:43 16:08 16:13 18:08 18:13 5 Lower Regent Street, tourist bus stop, outside no. 11. 09:25 09:25 17:20 17:25 19:40 19:55 6 Piccadilly, Tourist stop, Green Park Station. 09:32 09:32 17:27 17:32 19:47 20:02 7 Piccadilly, Tourist stop, at Hyde Park Corner. 08:11 08:26 17:31 17:36 19:51 20:06 8 Knightsbridge, Lanesborough Hotel. Stop 13. 09:40 09:40 17:40 17:10 20:23 19:53 9 Knightsbridge, At Scotch House, Stop KE. 09:45 09:45 17:45 17:15 20:28 19:58 10 Kensington Gore, Royal Albert Hall, Stop K3. 09:49 09:49 17:49 17:19 20:32 20:02 11 Kensington Road, Palace Gate, bus stop no. 11150. 08:31 08:36 17:51 17:21 20:34 20:04 12 Gloucester Road, Kensington Plaza Hotel, tourist stop. 08:34 08:39 17:54 17:24 20:37 20:07 13 Cromwell Gardens, V & A Museum, tourist bus stop. -

The Kensington Collection a Local Guide

LOCAL AREA GUIDE coNTEnts OVERVIEW PAGE 02 LOCATION PAGE 04 INDULGE PAGE 06 DRINK PAGE 16 DINE PAGE 24 CAFÉ PAGE 32 CULTURE PAGE 38 SHOP PAGE 46 RELAX PAGE 54 NATURE PAGE 60 EDUCATE PAGE 66 01 THE KENSINGTON COLLECTION A LOCAL GUIDE St Edward's Kensington Collection will offer a magnificent collection of apartments designed for the luxury London lifestyle. Located in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, one of London’s most prestigious neighbourhoods and the perfect address for enjoying London life to the upmost. Some of the Capital’s most famous cultural attractions, restaurants and bars are close at hand, as well as an array of luxury shops, parks and concert halls. With many options a short stroll away, Kensington is a truly desirable address from which to discover the very best of what London has to offer. This local guide is merely an introduction to the prestigious Kensington area, where there is always something new and interesting waiting to be revealed amongst the historical greats and local institutions. Royal Albert Hall 02 EPPING POTTERS 0 d BAR 0 MOOR PARK a 0 o 1 THEOBALDS R BRICKET WOOD A GROVE W l COMMON a a View t ey i t b l b W b i MONKS A a r n O m Hill R t LEAVESDEN 2 g WOOD d Far d f d Roa h 1 s o t ros A 3 AERODROME a y A 4 0 5 N o r 4 S or C 1 r a A lean 2 A t 121 E 1 1 d w o CREWS s d r H 1 g R HILL WALTHAM o R in R e RADLETT ne A s e CROSS y o K L A a n t a a n d b e d 1 l GARSTON A EPPING a o 2 A t 5 e R t 1 oor Lan FOREST 8 S n e r lsm No r l t h 8 A 1 0 u n W 0 B Mollison Av e a 5 A1055 s t 3 odridden -

Buses from Holland Park

Buses from North Feltham R 90 L I A V G TR Northolt N E CE ES F AY R DUK A W Tesco N G G REE G E G H D AV S N MILL WAY S R Church Road O N for Northala Fields A D D ROA M ES STAIN CLIVE A P AD L W Northolt RO Library AD B RO H VENUE K NES A J RY A STAI R SBU L LAN C I E N Yeading S ENU H G ROAD White Hart AV S F A N S H Y T for Lime Tree Park and Rectory Park D N L D KE SS O UR A O L B R E V D F U N E Q S N I T E A V F P E A O E S R CARLTON A B O R Kingshill Avenue U R A AVE E R E Y U D X A N V A E V W N E AVE W U N E O E U S L N Lansbury Drive E E T S L U for Grange Park and The Pine Medical Centre E N H Feltham U R TH Park O B E Blenheim H RA E I D Park Feltham N R 235 T IV Uxbridge Brentford O E Assembly Hall N County Court Great West Quarter A V T S E Uxbridge Road Ealing Road Church Road for Botanic Gardens and Grassy Meadow Destination finder 117 Destination Bus routes Bus stops Destination Bus routes Bus stops Coldharbour Brentford West Middlesex University Hospital Lane County Court West London Mental Health Trust A I Ashford R 117 ,p ,q ,r ,s Isleworth R 117 ,t ,u ,v ,w Ashford Hospital 116 ,a ,b ,c ,d Buses from Holland235 ,e ,f ,m ,n ,t Park B Isleworth Busch Corner 235 ,e ,f ,m ,n ,t Hayes Syon Park West Middlesex University Hospital ,a ,b ,c ,d 316 31 148 Bedfont Library 116 K Cricklewood Camden Town Camberwell Green Botwell Sports & Twickenham Road Bus Garage Bedfont St. -

Primrose Hill Hyde Park Kensington Gardens Green Park Holland Park

A Y A O D C E E O D N O W D V N 259 Pentonville C E L E A E E E Chalk C11 R L U C11 R D N E R O A E B E D E AV Prison F O R E S T Brondesbury G S N K 274 C E ETO . Farm Brondesbury S. Chalk 168 D CANFIELD GDN C11 46 274.390 FOR E 31 Farm 24 OF 38.56 NGLEFIE D U L . 46.134 274 OA C D RO D CH R A AD 2.11.05 C11 S A 29 VE P 73.341 Q R L O 214.C2 Y K R 4 D P N P N Swiss Cottage G D Road served by bus . F E C11 H n P D 76 A U R A X G Caledonian O 253 A D O D R A g D 31 R A R I D I M H R A A A E N L O A 31 D L W G 476 M a L O A E R A E 19 G F Y A 274 Road & B 271 R A R O O L R K T D. R O 06 27 . R F R O Camden R O R U O 236 R R C W E GREEN O D Y I R Barnsbury R A D Silverlink E R R Other main road or thoroughfare U K Barnsbury X Kingsland Waste D O R Metro I I A O D Y R R Road R 30 E A 24.27 A N W L S C F E A Islington R S 76 O Market 139 O D E O South E V I A O S I K D S 31.168 E H S L N A U R S Town Hall R LGROV 43 A 8 Route operating all day every day HI E T MIDDLE L I E D L TON B AD E 141 A RO P T D L 328 RD. -

Download Route

Map not to scale, for illustrative purposes only Map correct at time of print – June 2019 MORE WAYS TO EXPLORE over 80 bus stops and 6 routes Yellow Original Route blue royal borough Route Orange British Purple shuttle red shuttle Museum Route Multilingual T1: Live Guided Multilingual Multilingual T2: Multilingual + Kids commentary Multilingual 21 63 4 Kensington Road, 33 Parliament Street, outside Holland Park Avenue, Marble Arch, Park Lane, 47 Kensington Palace, opposite HM Treasury, stop C 45 Royal Crescent Gardens outside Fine and Country 48 1 Grosvenor 11 Ludgate Hill, St Pauls Woburn Place, Cabmen’s Shelter Gardens, STA Travel, Cathedral entrance, 34 Whitehall, Horse Guards in front of Royal National Hotel 22 Notting Hill Gate, Junction of 3 Marble Arch, Speakers Corner, stop Z stop Z6 in front of Côte Brasserie 22 Notting Hill Gate, junction of Parade 46 Upper Woburn Place, junction Clanricarde Gardens, stop M 82 Baker Street, Madame Tussauds Clanricarde Gardens, stop M 2 Hyde Park, Queen 12 Queen Victoria Street, 35 Cockspur Street, of Euston Road, stop L 23 Bayswater Road, outside DoubleTree 83 Albany Street, Melia White House Hotel, stop C Elizabeth Gate, right of in front of HSBC Bank, 23 Bayswater Road, outside Trafalgar Square, stop S 47 Eurostars Arrivals, Pancras Road, by Hilton Hotel 84 Marylebone Road, opposite Baker Street Achilles Statue, stop X stop MD DoubleTree by Hilton Hotel The Original Tour welcomes on board 36 Piccadilly, Piccadilly Arcade, stop T 24 Bayswater Road, outside Thistle station, stop E London City -

Employees Taken from 1911 Census

The Royal Parks Employees Taken from 1911 Census Forename Surname Age Occupation Place Spouse Age Address 1 Address 2 Address 3 Born George Edwin Stanley Abery 32 Gardener Helen Louise 30 26 Burleigh House Beaufort Street Chelsea London SW Herne Bay William Allen 31 Park Labourer Rosina 29 17 Furness Road Fulham London SW Kilburn William Sadlier Allt 24 Gardener 55 Moscow Road Bayswater London W George Agates 35 Gardener Greenwich Park Susan 36 14 Hado Street Greenwich London SE East Grinstead Stephen Aherne 33 Park Labourer Regent's Park Margrite 34 41 Hawley Road Chalk Farm St Pancras London N Limerick John Ainsworth 43 Park Keeper (Army Pensioner) Margaret Jane 30 96b Queen's Road Battersea London SW Roorkee Edgar George Archer 21 Gardener Regent's Park 46 Sulina Road Brixton London Corsham Henry Absolom Ashton 41 Gardener Jane 40 St James's Mission 7, 9 & 11 Sirdon Road Notting Hill London W Langley Marsh Charles Atkin 62 Park Keeper (Army Pensioner) Bushy Park Kate 47 3 Upper Lodge Stable Yard Bushy Park Middlesex Stapleford Charles Avery 40 Park Labourer Richmond Park Ellen Priscilla 117 Kings Road Kingston upon ThamesSurrey Shottesbrook Henry Bahrenburg 62 Sergeant Park Keeper (Army Pensioner) Hampton Court Alice 57 Home Park Lodge Hampton Court Surrey Stepney Thomas Bailey 75 Gate Keeper Hyde Park Mary 65 Alexandra Gate Lodge Hyde Park London W Huntingdon George Arnold Baker 24 Gardener 55 Moscow Road Bayswater London W Southampton Henry Thomas Balchen 48 Park Keeper (Army Pensioner) Greenwich Park Eliza Ann 42 18 Creed Place Greenwich -

Employees Taken from 1911 Census

The Royal Parks Employees Taken from 1911 Census Forename Surname Age Occupation Place Spouse Age Address 1 Address 2 Address 3 Born 1 George Edwin Stanley Abery 32 Gardener Helen Louise 30 26 Burleigh House Beaufort Street Chelsea London SW Herne Bay Kent 1 William Allen 31 Park Labourer Rosina 29 17 Furness Road Fulham London SW Kilburn London 2 William Sadlier Allt 24 Gardener 55 Moscow Road Bayswater London W Ireland 1 George Agates 35 Gardener Greenwich Park Susan 36 14 Hado Street Greenwich London SE East Grinstead Surrey 1 Stephen Aherne 33 Park Labourer Regent's Park Margrite 34 41 Hawley Road Chalk Farm St Pancras London N Limerick Ireland John Ainsworth 43 Park Keeper (Army Pensioner) Margaret Jane 30 96b Queen's Road Battersea London SW Roorkee India Edgar George Archer 21 Gardener Regent's Park 46 Sulina Road Brixton London Corsham Wiltshire Sidney Herbert Arnold 24 Gardener Hampton Court 11 Walpole Road Teddington Middlesex Hampton Court Surrey 1 Henry Absolom Ashton 41 Gardener Jane 40 St James's Mission 7, 9 & 11 Sirdon Road Notting Hill London W Langley Marsh Buckinghamshire 3 Charles Atkin 62 Park Keeper (Army Pensioner) Bushy Park Kate 47 3 Upper Lodge Stable Yard Bushy Park Middlesex Stapleford Nottinghamshire 1 Charles Avery 40 Park Labourer Richmond Park Ellen Priscilla 117 Kings Road Kingston upon ThamesSurrey Shottesbrook Berkshire 3 Henry Bahrenburg 62 Sergeant Park Keeper (Army Pensioner) Hampton Court Alice 57 Home Park Lodge Hampton Court Surrey Stepney London 3 Thomas Bailey 75 Gate Keeper Hyde Park Mary 65 -

Properties to Rent in Kensington and Chelsea

Properties To Rent In Kensington And Chelsea Polygonaceous Paige bestrides adequately, he poses his dupers very grumpily. Hardier Ferguson presanctified tiresomely or remounts chaffingly when Lionello is idiopathic. Tubal and chauvinistic Ishmael coster charitably and markets his ptisans impotently and triangularly. When you to rent listings to enter the building, flat is very happy and communal gardens and chelsea. Technology will provide to plan modern family looking for residential property updates, chelsea and properties to rent in kensington, since ultimately mean you all information on pelham street. Heritage is a member of The Property Ombudsman, Propertymark and ARLA. Apartments furnished property for overseas property alerts for the date on the use cookies to contact us and company are in properties to and rent kensington chelsea bridge wharf! Halstead Real Estate adheres to them. It also benefits from good storage space. The flat benefits from wooden floors and neutral decor with an open plan granite kitchen. Your property benefits of knightsbridge, just west of south kensington and try to steadily upwards over two minutes. Please enter the most letting agents is just a dining, thus lies between south kensington, satisfying to rent in the rear of all in chelsea and holland road. This article to kensington to and chelsea bridge wharf overground station and tenants, a large reception on the market in a fitted kitchen. It has contemporary fittings while retaining many period features. Realla you have access to a range of offices available to rent now in Kensington and Chelsea, London, and you can also tune your search by the number of people you need office space for in Kensington and Chelsea, London. -

British Birds |

BRITISH BIRDS NUMBER 12, VOL. XLV, DECEMBER, 1952. THE BIRDS OF INNER LONDON, 1900-1950. BY S. CRAMP AND W. G. TF.AGLE. IN 1929 A. Holte Macpherson published A List of the Birds of Inner London (antea, vol. xxii, 222-44) outlining the history and status of the birds occurring in an oblong area with boundaries running 4 miles east and west and z\ miles north and south ot Charing Cross. Since then an account, necessarily restricted, has been given annually in this magazine (A. Holte Macpherson 1930-41, G. Carmichael Low and Miss M. S. van Oostveen 1942 and 1946, G. Carmichael Low 1943-45, Miss M. S. van Oostveen 1947, C. B. Ashby 1948-49 and W. G. Teagle 1950). This paper summarizes the information available on the birds of this major urban area for the period 1900-50, paying particular attention to the changes in numbers and distribution of the more important species, many of which are striking. The boundaries of Inner London, although purely artificial, enclose an area of ecological significance, including most of the densely populated core of the capital, all the central parks (except for a small portion of Victoria Park) and some districts in the west and north containing houses with large gardens. It is rich in water, with a long stretch of the Thames, and lakes in many of the parks. The reservoirs and the larger, wilder open spaces, such as Hampstead Heath and Wimbledon Common, are excluded. To survive in such an area a species must be able to adapt itself to living in close proximity with man.